Edit article

Edit articleSeries

In Search of the Soul: Between Torah and Science

Pixabay, adapted

Introduction— Goodbye to the Gute Neshama?

Neshama was a word I frequently heard in my parents’ home. In Yiddish, א גוטע נשמה (a good soul) was a high compliment. And a Hebrew-speaking friend in Israel recently told me that he took up sculpture because it was “good for his נשמה.” But in English, “soul” seems to have vanished from our every-day conversation. It lingers on mainly as a kind of music or food, its distinguished time-worn position apparently replaced by neuroscience.

So is it time to say good-bye to the soul and consign it to the dustbin along with the four humours and the ether? I don’t think so… at least, not exactly.

Part 1

The Soul in Jewish Tradition

Our current understanding of the English word ‘soul’ is undoubtedly influenced by its usage in our ambient Christian culture. But what were the original meanings of the Hebrew words we translate as soul?

- נפש (nefesh) derives from the word for neck, which appears, e.g., in the biblical expression “the water reached the neck” (מים עד נפש) found in Jonah 2:6 and Psalms 69:2. More generally, the term means living being, life, self, or person, and can even express derivative concepts such as desire, appetite, emotion or passion.

- נשמה (neshama) derives from the root נ-ש-מ, which refers to breathing, and is used in the verb לנשום, to pant, (in Modern Hebrew, to breathe) and the modern Hebrew word for breath (נשימה). The term can also mean life or spirit, based on the equation of breathing equals life, as in:

וַיִּפַּ֥ח בְּאַפָּ֖יו נִשְׁמַ֣ת חַיִּ֑ים וַֽיְהִ֥י הָֽאָדָ֖ם לְנֶ֥פֶשׁ חַיָּֽה

[The LORD] blew into his nostrils the breath of life, and man became a living being (Gen 2:7).

- רוח (ruach) literally means wind or the movement of air when breathing. Ancient Israelites connected life with bodily movements associated with breathing, such as flaring of the nostrils. The term ruach can also mean life, breath, or spirit, especially when combined with the term נשמה as here:

כֹּ֡ל אֲשֶׁר֩ נִשְׁמַת־ר֨וּחַ חַיִּ֜ים בְּאַפָּ֗יו… מֵֽתוּ:

All in whose nostrils was the breath of life… died (Gen 7:22).

All three Hebrew terms relate to the physical process of breathing, or more accurately perhaps, ventilation.

A Detached Soul

In addition to the biological meaning of soul, however, “the evidence suggests that a belief in the existence of disembodied souls was part of the common religious heritage of the peoples of the ancient Near East.”[1] Richard Steiner, a Bible and Semitics scholar from Yeshiva University, makes a well-documented case that the idea of soul distinct from the body was already present in the Hebrew Bible before any influence from Greek thinking. Certainly, by the rabbinic period, the נשמה was conceived of not merely as the life force of the body but as an independent entity, something deposited by God into the human being.

Liturgy

Thus we thank God in the Modim prayer of the daily Amidah

על חיינו המסורים בידך,

ועל נשמותינו הפקודות לֹך.

For our lives which are entrusted into Your hand,

And for our souls which are placed in Your charge.

The implication here is that the soul is akin to a security (פיקדון, pikadon) deposited into the body and detachable from it.[2] It is a sort of energy-providing battery that is removed at death and in sleep but available to the body once again on waking and when life resumes after death.

This idea is found as well in the selichot prayer (הנשמה לך והגוף שלך, “the soul is yours and the body is yours”), and in the rabbinic concept of the Jew’s extra soul (נשמה יתירה, Soferim17:4). Similarly, the Talmud discusses the נשמה of a righteous person, implying that this is what causes such a person to act properly (b. Sanhedrin 103b).

Resurrection

This can also be seen in Rabbi Yehudah HaNasi’s famous explanation for why there must be resurrection, which opens with a question from his gentile friend Antoninus (b. Sanhedrin91a-91b):

אמר ליה אנטונינוס לרבי: גוף ונשמה יכולין לפטור עצמן מן הדין, כיצד? גוף אומר: נשמה חטאת, שמיום שפירשה ממני – הריני מוטל כאבן דומם בקבר. ונשמה אומרת: גוף חטא, שמיום שפירשתי ממנו – הריני פורחת באויר כצפור.

Antoninus said to Rabbi [Yehudah HaNasi]: “The body and the soul (neshama) can exempt themselves from punishment. How? The body says: ‘The soul sinned, for from the day it left me I have been lying in the grave still as a stone.’ The soul says: ‘The body sinned, since from the day I left it I have been flying in the air like bird.’”

After offering a parable, Rabbi Yehudah HaNasi responds by saying that this is why God resurrects the dead, so that the whole person can receive his or her reward or punishment.

Part 2

The Soul in Science and Medicine

It now appears, however, that biology and neuroscience can better explain much of what the idea of the soul once explained. Let’s look at some examples of this.

Breathing

Ancient Israel’s equation of life with breathing and flaring of the nostrils is unacceptable now scientifically because it would mean that creatures such as plants and insects—which respire but do not breathe in the ordinary sense—are not alive! It turns out that life is not limited to creatures that breathe. Breathing is only one way by which living creatures gain the oxygen necessary to sustain themselves. Humans breathe because neurons of the lower medulla-oblongata sense acid-base changes in blood causing the diaphragm to move. Life depends on this mechanism—not on soul.

The Mind

We said above that the term soul includes aspects of mind such as desire and emotion. Michael Carasik details the biblical terms used to describe the receptive, retentive, and creative aspects of what we now call mind.[3] But it is the heart, he notes, that “is the physical locus most commonly presented in the Bible as that of the mind, comparable to the head in modern English.”[4]

The oft-recited first paragraph of Shema— “with all your heart and with all your soul (בכל לבבך ובכל נפשך)”—distinguishes between heart and soul and implies that “soul” (נפש) must be something other than “heart” (לב). So which word,[5] if any, corresponds to our current ideas about mind—לב or נפש? The matter is confused because the biblical authors, like other ancient people, lacked knowledge of the brain as the source of mind.

The Brain as the Organ of Mind

Our conception of “mind” as the summary of all brain functions—including rational thought, feeling, planning, calculating, desiring, etc.— is quite recent. The biblical authors had no unifying explanation for these aspects of mind that we now know are functions of the brain. For this reason, the intricate systems developed by the medieval Jewish philosophers and rabbis that attempted to relate soul to mind have little explanatory power for us today,[6] having been bypassed by neuroscience.

Ancient Conceptions of the Physical Source of Mental Functions

Absent any understanding of what the brain did, ancient thinkers, including the biblical authors, conceived of the heart, kidneys, liver, and other organs as the sources of emotions and mental functions. For this reason, in an attempt to preserve the body for the afterlife, the ancient Egyptians embalmed organs and kept them in canopic jars. They would also preserve the heart inside the body. But they destroyed the brain and poured it out through the nose as useless garbage.

As late as the 16th century, the English philosopher Henry Moore dismissed the brain and declared that “this laxe pithe (sic) or marrow in man’s head shows no more capacity for thought than a Cake of Suet or a Bowl of Curds.”[7]

Discovering the Brain and the Nervous System

A great change in thinking was pioneered by the English physician Thomas Willis (1621-1675). Willis, the founder of neurology, compared his patients’ signs and symptoms during life with areas of damaged brain he found through clandestine autopsies. (Our present-day imaging studies are a continuation of this same highly fruitful approach.) Rapid progress ensued.

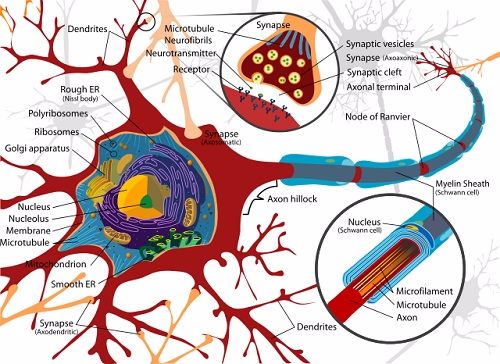

By perfecting the new methods of staining cells with different dyes, Santiago Ramón y Cajal (Madrid, 1888) discovered that the nervous system is made up of individual cells touching one another. These cells, later called “neurons,” are the basic unit of the nervous system. Neurons generate an electro-chemical signal (the action potential) that travels along a branched “wire“ or axon to connect with or “talk to” other neurons at connecting points called synapses. Each synapse is enormously complicated, and each of the hundreds of billions of synapses in our brain is capable of reintegrating its past experience or pattern of activity to determine its future excitability. Memory and learning are thought to be based on such changes in synaptic connections.[8]

Populations of neurons are organized into modules that specialize in one or another brain function, such as making sense of what we hear or see, planning, feeling, language and remembering. All of these capabilities taken together are called “mind.” Thus, soul considered as mind is no longer mysterious and adds nothing to our scientific understanding. Mind is simply what the brain does.[9]

The Self

“[I]t was her soul more than her body that knew fear. She had realized for the first time, with finality and fatality what was the illusion she laboured under. She had thought that each individual had a complete self, a complete soul, an accomplished I. And now she realized as plainly as if she had turned into a new being, that this was not so. Men and women had incomplete selves, made up of bits assembled together loosely and somewhat haphazard.” – D.H. Lawrence, The Plumed Serpent[10]

The opening verse of Psalm 103 reads:

בָּרֲכִ֣י נַ֭פְשִׁי אֶת יְ-הֹוָ֑ה

וְכָל קְ֝רָבַ֗י אֶת שֵׁ֥ם קָדְשֽׁוֹ:

Bless the LORD, O my soul,

and all that is within me His holy name.

The first and second cola of the verse are parallel.[11] Thus, “Yhwh” is parallel with “His holy name,” and “my soul (נפשי)” with “all that is within me (כל קרבי).” These latter phrases (“my soul” and “all that is within me”) are likely trying to convey the concept of “myself” or “my being.” Nefesh frequently has this meaning in the Psalms and in the Siddur.

Explaining the Feeling of “Selfness” and Where in the Brain It Resides

The mysterious feeling of “selfness” was explained in the past by the concept of a soul, which represented a person’s essence. In recent years, however, neuroscience has made great strides in understanding how the brain produces this feeling of self and how we each construct our inner “me.” In fact, we even have a good idea as to where in the brain this feeling is produced.

Recent studies point to the medial prefrontal cortex (MPFC), the area along the midline of the frontal lobes anterior to the motor area, as a key neural structure for processing various kinds of information relative to the self.[12] The ability to think about oneself in abstract and symbolic ways is a function of the frontal cortex—a part of the brain that expanded dramatically during mammalian and human evolution and accounts for our distinctively high foreheads.

The MPFC places information about ourselves based on our multiple past experiences onto a continuum of self-relevance. This collected information constitutes the self-concept and is stored in brain areas that are the loci of long-term memory. This is where “I” resides.[13] It may feel as though my soul— that is, “all that is within me”— blesses God, but in fact, it is one specific area of the brain that generates that feeling.

Conscious Awareness

The blessing recited over waking up in the morning ends: “…who restores souls to lifeless bodies (המחזיר נשמות לפגרים מתים).” But sleeping bodies are not lifeless. The autonomic nervous systems that regulate heart rate, blood pressure, respiration, digestion, renal function, and all the panoply of processes that keep us alive are all maintained during sleep. What does change in sleep is our level of consciousness and awareness of our surroundings. Again, neuroscience offers an explanation for this phenomenon.

What Happens to Awareness during Sleep

The states we think of as conscious or awake are dependent on the activity of the reticular activating system, a network of neurons in the brainstem that sends projections throughout the thalamus, hypothalamus, and cerebral cortex. These projections release nerve-signaling chemicals called neurotransmitters that control whether we are asleep or awake by acting on different groups of neurons. Neurotransmitters such as serotonin and norepinephrine keep some parts of the brain active during our wake state. As we fall asleep, other neurons at the base of the brain release acetylcholine that “switches off” the signals that keep us awake. As one might imagine, the prefrontal cortex—the area involved in so-called “executive functions” of the brain and the source of the concept of self—is deactivated during sleep.[14]

It is because of these changes in neurotransmitter activity that we are less able to react to environmental stimuli, integrate information, focus attention, or control our behavior during sleep. From the neurologic point of view, “restoring souls to lifeless bodies” on waking is no longer mysterious. It is a matter of changes in neurotransmitter activity.

The “Activating Principle” of Life

Life and death have always called for an explanation. An ancient solution to their mystery was that the soul’s presence constitutes life; its absence accounts for death. The soul was the “activating principle” of life. When philosophers—or “natural scientists” as they were once called—discussed the term “activating principle,” they were not picturing physically sustaining substances like oxygen and glucose that produce the energy to power our bodies. Rather, they thought of an animating, non-physical principle in living things that rendered them fundamentally different from non-living entities.

The concept of elan vital, the vital force or impulse of life, persisted into modern times and was advanced by French philosopher Henri Bergson as late as 1907. Nevertheless, this concept is no longer part of the way biology conceives of life.

Synthesizing Organic Compounds in the Laboratory

In 1828, the German chemist Friedrich Wöhler synthesized the organic compound urea from inorganic chemicals on his laboratory shelf. This inorganic urea was identical to that which is regularly excreted by humans as a way of ridding our body of nitrogenous waste. The key point is this: there is no vital principle inherent in organic urea that makes it any different from synthetic urea! Both living and non-living things conform to the same physico-chemicalprinciples.

This is not to say that living things are not different from non-living things. Living things, for instance, have highly complex molecules not present in non-living things. An example isdeoxyribonucleic acid (DNA), a double-stranded chain of nucleic acids that coil around each other in a helical ‘twisted ladder’ structure. A sugar-phosphate backbone is on the outside of this double helix and the nucleotides adenine, guanine, thymine and cytosine are in the inside. The information in this double helix is ‘transcribed’ into the closely related ribonucleic acid (RNA) that serves as a template for producing proteins.

But a molecule of DNA doesn’t differ in any fundamental way from a non-living molecule, such as water or ammonia. All molecules, living and non-living, are dependent on the properties of atoms and their physico-chemical bonds. It happens that molecular DNA is of immense importance, since it encodes the “recipe” for living beings. But it does not depend on any outside non-physical, non-chemical “vital force.” While it is clear that a living system is something quite different from an inanimate object, “… not one of life’s characteristics are in conflict with a strictly mechanistic interpretation of the world.”[15]

From a neuroscience point of view, therefore, the use of “soul” to mean the mysterious vital force or פיקדון deposited into the body and responsible for life is unacceptable— because there is no such force. It has been replaced in our understanding by the biochemical processes that sustain living beings.

Part 3

The Soul in Philosophy and

Religious Psychology

Since soul is no longer a useful explanation for life or mentation, should it be jettisoned altogether? I think not.

Soul has another meaning that we have ignored to this point. This becomes clear when soul’s meanings are considered as lying along a continuum— from the physical to the abstract:

- Physiological – Soul here refers to physiologic functions that characterize life, especially breathing. (This is a common biblical usage.)

- Mental – This is an intermediate usage in which soul refers to mind, personality, consciousness, self, and related mental functions, whose origins we now know are inbrain.

- Spiritual – Soul here is abstract, with no connection to breathing or brain, the intangible precious soul of religion and philosophy.

This concept of a spiritual soul situates us in the cosmos as creatures created in God’s image (Gen 1:27, 5:1, 9:6). By dint of this aspect of soul, we gain dignity and our lives gain meaning. This is the pure soul of the morning prayer, “My God, the soul You placed within me is pure (אלהי נשמה שנתת בי טהורה היא).” This pure soul lives on after us. It is in our thoughts when we raise a glass of schnapps on a yahrzeit for one whom we wish לעלוי נשמת— an ‘elevation of the soul’ in heaven. This kind of soul will never be replaced by neuroscience.

Some would object to the idea of a spiritual soul on the grounds that it is merely an illusion generated by our brain. Perhaps this is so. And it may be true that the feeling that we are something special in the cosmos— something divine— served to rally us to survive adversity in our evolutionary past. But, so what? I don’t think that the pure soul’s possible usefulness in our evolutionary past negates its truth. We have a choice here. We can dismiss the idea of an ethereal or divine soul as resulting from an evolved way of thinking in human beings that has no basis in the way things really are. Or, we can integrate a concept that feels meaningful to us into the fabric of our lives, to give us hope and dignity, despite the fact that we will never know whether or not such a soul exists. I choose the latter.

The Utility of the Spiritual Soul in Poetry and Literature

We can see the utility of keeping this more ephemeral concept of the soul when we turn to poetry and literature. To drive the point home, consider what would happen if we tried to use biological concepts of soul in prayer or Bible study:

Nefesh: Psalms 103 and 104, which open with the words ברכי נפשי (bless my soul), would be translated as: “bless the self that my brain constructs from representations in my medial frontal lobes.”

Neshama: The prayer said on waking that thanks God, “who has restored my soul to me (שהחזרת בי נשמתי)” would become, “…who has restored the system by which my evolved brainstem neurons activate cortical centers responsible for arousal to conscious awareness.”

Ruakh: We might describe the “spirit of wisdom (רוח חכמה)” that filled Bezalel in designing the Tabernacle as his “visual-spatial skills originating in the right cerebral hemisphere.”

The translations are undoubtedly “accurate” scientifically speaking, but how absurd these understandings of soul become outside the world of science! These precise definitions detract from the dignity, awe and mystery of the original Hebrew words. In fact, the very lack of clear definition of these words may be their strength, permitting us to assign to them our own shades of meaning.

Greater than the Sum of Its Parts

Thus, נפש ,נשמה, and רוח each evoke a composite of meanings whose sum is greater than its parts. For example, when we translate נשמה as breath— as in ויפח באפיו נשמת חיים Gen 2:7 “and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life” — the term נשמה resonates with its other meanings: soul, spirit, or living being. Similarly, נפש in the phrase, ויהי האדם לֹנפש חיה — “and man became a living soul”— carries with it the additional meanings of self and personhood. The ambiguity of these terms adds to their meaningfulness.

The Meaningfulness of Soul

Human beings continue to search for meaning, for our own place in this unimaginably vast cosmos. We yearn for lives that matter and for something larger and more lasting than ourselves. Despite our greater understanding of the biological and neuroscientific roots of some aspects of soul, other concepts of soul involving human dignity and divinity persist that fill this human need. They remain beyond science.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

April 10, 2016

|

Last Updated

April 12, 2024

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Footnotes

Dr. Joel Yehudah Rutman, M.D., is a graduate of Brandeis University and Harvard Medical School with certification in Pediatrics and in Neurology and Psychiatry with Special Competence in Child Neurology. He was Clinical Professor of Paediatrics (Neurology) at the University of Texas Health Science Center (San Antonio). Rutman also served as hazzan at Rodfei Shalom Congregation i(San Antonio). He is the author of, Why Evolution Matters: A Jewish View.

Essays on Related Topics: