Edit article

Edit articleSeries

A Personified Reed Sea

Crossing the Reed Sea by British artist & illustrator William F. Phillipps 1964 The Illustration Art Gallery

What Did the Waters Do at the Blast of YHWH’s Nostrils?

Following their escape from the clutches of the Egyptians, Moses and the Israelites chant the “Song at the Sea.” Exod 15:8 reads:

וּבְרוּחַ אַפֶּיךָ נֶעֶרְמוּ מַיִם

נִצְּבוּ כְמוֹ נֵד נֹזְלִים…

At the blast of your nostrils the waters neʿermu,

The floods stood still like a wall…

But what is the meaning of the verb נערמו, which is used in the Bible only here?[1]

1. The Water Piled Up

The verb is typically connected to the nominal form ערמה/ערמות, “pile,” thus yielding “the waters piled up” (NJPS) or “stood up in a heap” (NRSV). This translation goes back at least as far as the Mekhilta of R. Ishmael (Masechta de-Vayehi 4):

נעשה ערימות שנ’ וברוח אפיך נערמו מים

They were made into piles, as it says (Exod 15:8): “At the blast of your nostrils the waters piled up.”[2]

This interpretation is accepted by the vast majority of traditional and modern commentators.

2. Stripped

A second possible etymology connects נערמו to the word for nudity, ערום. Midrash Esther Rabbah (3:14) takes this approach:

א”ר נתן אף מצריים ברידתן בים לא נידונו אלא ערומים מה טעם (שמות ט”ו) וברוח אפך נערמו מים,

R. Nathan said: “Also the Egyptians, when they went down to the bottom of the sea, were judged only once they were naked. What is the source? ‘At the blast of your nostrils the sea stripped them.’”

William Propp accepts the connection with nakedness, but assumes that it is the seabed that was stripped, not the Egyptians, and offers this piquant rendering: “the sea bottom was stripped of its water.” He supports this interpretation with 2 Sam 22:16:

וַיֵּרָאוּ אֲפִקֵי יָם

יִגָּלוּ מֹסְדוֹת תֵּבֵל

בְּגַעֲרַת יְהוָה

מִנִּשְׁמַת רוּחַ אַפּוֹ.

The Sea’s channels appear,

The earth’s foundations are revealed,

At YHWH’s roar,

From the breath of his nostrils’ wind.

3a. The Water Acted Slyly

A very different approach connects the waters’ action to the root ע.ר.מ meaning “craftiness.” The Mekhilta of R. Ishmael (Masechta de-Shira 6) suggests this reading, viewing the waters’ action as a talionic response to the cruelty and craftiness that the Egyptians had displayed towards the Israelites:

וברוח אפך נערמו מים, במדה שמדדו בה מדדת להם. הם אמרו הבה נתחכמה לו אף אתה נתת ערמה למים והיו המים נלחמים בהם בכל מיני פורעניות לכך נאמר וברוח אפיך נערמו מים.

“At the blast of your nostrils the waters became crafty” – with the measure they measured with you measured them. They said (Exod 1:10), “let us deal shrewdly with them,” so too, you gave craftiness to the waters, and the waters fought with them with all manners of torment. Thus, it says, “at the blast of your nostrils, the waters became crafty.”

This interpretation was also adopted by Targum Onqelos:

וּבְמֵימַר פּוּמָּךְ חֲכִימוּ מַיָּא

And with the word of your mouth the water became wise/shrewd.

Rashi understands Onqelos to be saying the same thing as the Mekhilta, namely that shrewdness or craftiness (לשון ערמיות) entered the waters so they would dry out for the Israelites but drown the Egyptians. R. Chaim Paltiel (13th cent.) interprets similarly:

וזהו חכמתן שהיו מכסים למצרים ויבשה לישראל.

This was their wisdom: they would cover the Egyptians but dry out for the Israelites.

3b. Wise and Pious Waters

A number of commentators adopted yet another (albeit, unlikely) interpretation of Onqelos, namely that the Sea was imbued with wisdom – rather than craftiness (in Hebrew and Aramaic חכמה can mean either – thereby enabling it to join Israel in singing the deity’s praise following his intervention on Israel’s behalf. For example, R. Aharon ben Yossi HaKohen (13th cent.) writes (Sefer HaGen ad loc.):

נערמו מים – על מה שתירגם אונקלוס חכימו מיא, נערמו לשון ערמה וחכמה. וקשה, מה חכמה שייכא במים? וא”ל הר”ר משה ב”ר שניאור דיש מדרש בפירוש שנכנסה בהן ערמומית של חכמה ואמרו שירה.

“The waters neʿermu” – regarding Onqelos’ translation “the water became wise,” [he is understanding] neʿermu as related to ʿorma, cunning and wisdom. But this is difficult – what relevance does wisdom have to water? R. Moshe son of R. Shneur said to us that there is a midrash that states explicitly that cunning wisdom entered [the waters] and they sang [the Song of the Sea with Israel].[3]

Whichever understanding of “wisdom” one prefers, most modern commentators discount reading נערמו as related to ערמה (craftiness) as “far-fetched” (to quote William H.C. Propp; AB, p. 521). In his commentary on Exodus, Thomas B. Dozeman (Eerdmans, p. 324) further observes that this translation makes the verse incoherent as a whole, since no connection exists between the blast of divine air (וברוח אפיך) and the waters’ acquisition of craftiness [4] (נערמו מים). Nevertheless, as “far-fetched” or midrashic as such an interpretation may seem, it finds support from a textual variant in Deut 11:4.[5]

“Pursuing You” – Standard Text

In exhorting Israel to obey God’s commandments, Moses reminds the people that they personally saw –

דברים יא:ד וַאֲשֶׁר עָשָׂה לְחֵיל מִצְרַיִם לְסוּסָיו וּלְרִכְבּוֹ אֲשֶׁר הֵצִיף אֶת מֵי יַם סוּף עַל פְּנֵיהֶם בְּרָדְפָם אַחֲרֵיכֶם וַיְאַבְּדֵם יְהוָה עַד הַיּוֹם הַזֶּה.

Deut 11:4 and what He (i.e., YHWH) did to Egypt’s army, its horses and chariots; how he rolled back upon them the waters of the Sea of Reeds when they were pursuing you, thus YHWH destroyed them once and for all.[6]

The straightforward formulation “ברדפם אחריכם,” referring to the Egyptians’ pursuit of Israel, is also reflected in LXX, the Samaritan Pentateuch, and (most of the) textual witnesses from Qumran, and requires no elaboration.

“Pursuing Them” – Variant Text

However, another reading, “when they were pursuing them” [7] (ברדפם אחריהם), is attested in the Kennicott Bible, an MT text produced by the Spanish scholar, Moses ibn Zabara, in 1476. According to this reading, Moses refers to the (Reed Sea) waters’ pursuit of the Egyptians, ostensibly referring to the waters’ drowning the Egyptians. This reading is also reflected in some manuscripts of Targum Onqelos which read [8] בתריהון, and may be attested in a Qumran phylactery exemplar, 4QPhylk.[9]

To be sure, this reading may simply be the result of scribal error resulting from a variety of factors [10](e.g., the graphic/aural similarity between “אחריכם” and “אחריהם”), but it is difficult to ignore its multiple attestations.

Connecting the Midrash in Exodus and the Variant in Deuteronomy

Kennicott’s variant reading of Deut 11:4 yields a depiction of the Reed Sea’s role notably similar to the position of the Mekhilta adopted by Onqelos (among others),[11] that depicts the Reed Sea actively assisting Israel in its flight from the Egyptians. Yet, almost no rabbinic sources make reference to Deut 11:4 as evidence for the sea’s active role in drowning the Egyptians.

Ḥizquni

The one exception is the 13th century exegete, R. Hezekiah ben Manoah (Ḥizquni), who writes in his commentary to Deut 11:4:

…אשר הציף מי ים סוף על פניהם ברדפם אחריהם – ברדוף המים אחרי המצרים, והיינו דכתיב: נערמו מים, שתרגם אונקלוס: חכימו מיא, שחכמו והערימו לעשות רצון בוראם לרדוף אחרי המצרים

… “how he rolled back upon them the waters of the Sea of Reeds when they were pursuing them” – when the waters were pursuing the Egyptians. That is what is written: “the waters neʿermu” which Onkelos translates as “the waters gained wisdom,” they became wise and crafty about how to fulfill the will of their creator to chase after the Egyptians.

Ḥizquni argues that the reading “אחריהם” at Deut 11:4 indicates that the Egyptians had been pursued by the Reed Sea waters, as reflected in Kennicott, et al.; furthermore, he maintains, this notion is consistent with the meaning of Exod 15:8, as rendered in Tg. Onq. (ad loc.), which Ḥizquni apparently accepts as the simple meaning of the text. Thus, in Ḥizquni’s view, Exod 15:8 and Deut 11:4 express the same tradition, that the waters of the Reed Sea were engaged in purposive pursuit of the Egyptians.

Variants in Rabbinic Texts

To be sure, the presence of textual variants as recorded in (or implied by) medieval exegetical sources is hardly an unknown phenomenon. Thus, Jordan Penkower has noted at least four instances in which Rashi’s commentary reflects a different biblical Vorlage,[12] while Sara Japhet has identified more than twenty textual variants in Rashbam’s commentary to the book of Job.[13] (Numerous textual variants of the biblical text are also preserved in classic rabbinic works, e.g., Sifre Numbers, Sifre Deuteronomy.[14]) Thus, the variant in the Ḥizquni is just one example, though a significant one, of this broader phenomenon.

Kashering Ḥizquni

Some traditional scholars, including the editor of the standard printing of the Hizquni, Charles Chavel (1906-1982), assume that Hizquni was working with the standard text.[15] He ends his gloss with:

ואין לומר כלל שיש שום רמז ח”ו במשמעות רבינו לשינוי כתיבת תיבה בתורה.

And it should not be suggested at all that there is the least hint– heaven forfend! – in the words of our rabbi (Hizquni) of a difference in the writing of a word in the Torah.

This explanation involves special pleading and entails a contorted reading of Ḥizquni’s formulation and that of Deut 11:4. Yet, even according this (unlikely) understanding of Ḥizquni’s comments, the exegetical payoff remains; Deut 11:4 portrays the Reed Sea as having (actively) pursued the Egyptians, a notion that Ḥizquni views as entirely consonant with – though more explicit than – the biblical formulation at Exod 15:8.

Admitting the Variant

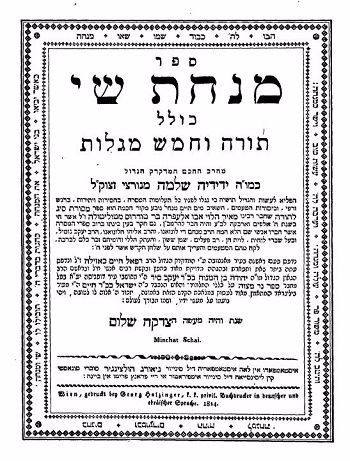

The compendium of Yedidiah Solomon Norzi (Matua, Italy, 1560-1626), Minḥat Shai, records numerous variants – orthography, word division, paragraph division, etc. – preserved in biblical manuscripts and attested (or reflected) in rabbinic and medieval sources. Though not a linguistic or philological treatise, this work is valuable not only for the breadth of explicit variants culled but, moreover, for Norzi’s keen ability to detect the presence variants implicit in post-biblical formulations and commentaries. In his remarks ad Deut 11:4, Norzi notes:

The compendium of Yedidiah Solomon Norzi (Matua, Italy, 1560-1626), Minḥat Shai, records numerous variants – orthography, word division, paragraph division, etc. – preserved in biblical manuscripts and attested (or reflected) in rabbinic and medieval sources. Though not a linguistic or philological treatise, this work is valuable not only for the breadth of explicit variants culled but, moreover, for Norzi’s keen ability to detect the presence variants implicit in post-biblical formulations and commentaries. In his remarks ad Deut 11:4, Norzi notes:

ברדפם אַחֲרֵיכֶם: מה מאד יש להפלא מהחזקוני שכתב אחריהם, ופירש… וכן בתיקון ס”ת ישן מצאתי גמגום זה, וגם במקרא גדולה כתי’ בהגהה צ”ע לרז”ל אחריהם, ע”כ.

“As they pursed you” – it is much to be wondered at that the Ḥizquni wrote “them” and explained… I also found this error in correcting an old Torah scroll. Also, in a Miqra Gedolah (a rabbinic Bible) there was a gloss which said, “Our Sages’ [text], ‘them,’ needs to be thought about carefully.”

Norzi is rather dismissive of this reading (he calls it an “error”) but continues by expressing astonishment at the absence of midrashic allusions to this textual variant. Indeed, Norzi notes that although several rabbinic sources reflect exegetical motifs similar to that entailed by the reading “אחריהם,” none of these sources (except Ḥizquni) requires that this reading be viewed as present in their Hebrew text.

The Relationship between the Variant and the Reading of Exodus 15:8

What is the nature of the diachronic relationship between the reading “אחריהם” and (the understanding of) Exod 15:8 as describing cunning or wise waters? First, it is entirely conceivable that the variant reading of Deut 11:4, though not explicitly cited in any known rabbinic source, served as the catalyst for the rabbinic and medieval depictions of the Reed Sea’s active role.

At the same time, given the symbiotic relationship between scribal intervention and the “pliable” nature of the text of the Hebrew Bible in the late Second Temple period, the reverse scenario of textual development also warrants serious consideration; that is, it is possible that the understanding of Exod 15:8 as referring to the Reed Sea’s cunning antedates the medieval attestations of this reading – as well as its possible attestation in 4QPhylk – and, in fact, informed the subsequent textual (re)formulation of Deut 11:4.

Finally, it is possible that the reading “אחריהם” is “original” (or at least, of similar antiquity)and that the understanding of “נערמו” as involving personification of the Sea accurately reflects the meaning of Exod 15:8. If so, then the two passages are simply expressive of a shared tradition involving the willful participation of the Reed Sea.

Whatever one’s understanding of the relationship between the texts of Exod 15:8 and Deut 11:4, the present analysis reveals that there is good reason to view the reading “אחריהם” at Deut 11:4 as constituting a (literarily and contextually) bona fide (and ancient) textual form.[16]

Understanding the Crafty Sea

Putting aside questions text criticism and which manuscript readings were known when, what does the text mean? Is the verse picturing what the Sages of the midrash suggest, that the waters of the sea became wise and crafty? This is, to be sure, how Hizquni takes it, but I do not think that reading “אחריהם” needs to be understood as entailing full-blown personification of the sea. The scribe(s) responsible for this reading may have understood this formulation to mean simply that the sea waters, when engulfing the Egyptians, appeared to be in pursuit of them. In fact, this is how R. Bahya ben Asher (1255-1340) reads Exod 15:8:

נערמו מים. על דרך הפשט כתרגומו: חכימו מיא, והכוונה בזה כאלו התחכמו המים כאשר קמו נד אחד להמציא בים דרך לעבור גאולים ולנער את המצריים בתוכה אחרי כן כשישובו כבתחלה לאיתנם.

“The waters neʿermu” – The simple reading is in line with [Onkelos’] translation: “The waters gained wisdom.” The intention here is that it was as if the waters were acting with cunning, for when one part of the water stood straight up to make way for the redeemed ones to pass, and [then] to hurl the Egyptians inside it, and afterwards it returned to its previous calmness.

Nonetheless, the personification of the sea reflected in this reading of Deut 11:4 is entirely consonant with the nature of the verse’s broader context. Indeed, the following verse, like Num 16:32, refers to the earth opening its mouth (“אשר פצתה האדמה את-פיה”) and swallowing the followers of Dathan and Abiram and their households.

Personifying the Sea in the Hebrew Bible

The Hebrew Bible personifies the sea—Reed Sea or otherwise—in various contexts (and is even more broadly attested in rabbinic sources).

- Ps 114:3-5, describes the Sea as “fleeing” – presumably, upon “seeing” the presence of the deity.[17]

- Ps 74:12-15 depicts the slaughter of the sea (i.e., sea dragon).

- Job 7:12 parallels the Sea with the primordial serpent as being in need of watching over.

- In several passages the deity is said to “rebuke” or, possibly, “roar [at]” (root, גער) the sea, which then submits to the awesome power and majesty of the deity.[18]

In light of the above, the reading “אחריהם” at Deut 11:4 should not occasion surprise; indeed, an ancient reader encountering the formulation “אחריהם” at Deut 11, with its personification of the sea, would likely not view this reading as involving any literary “aberration” or infelicity. Instead, the passage would have been understood as yet another example of the personified sea in the Bible, though this time instead of fighting against God, it behaves in line with God’s intention to save the Israelites and drown the Egyptians.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

August 10, 2017

|

Last Updated

March 27, 2024

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Footnotes

Dr. David Rothstein is a Senior Lecturer in Ariel University’s Israel Heritage Department. He holds a Ph.D. and an M.A. from UCLA’s Department of Near Eastern Languages and Cultures. He is the author of the commentary to 1 and 2 Chronicles in The Jewish Study Bible as well as a number of articles, such as, “Deuteronomy in the Ancient Versions: Textual and Legal Considerations.”

Essays on Related Topics: