Edit article

Edit articleSeries

Afflicting the Soul: A Day When Even Children Must Fast

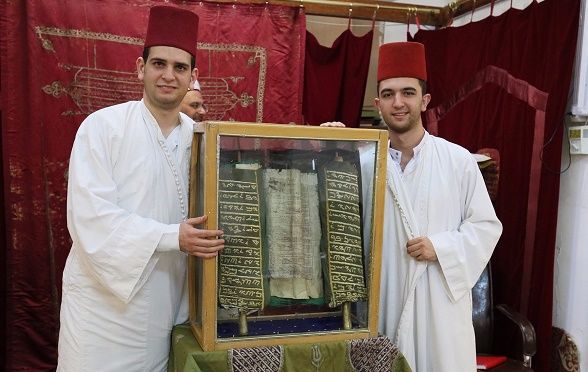

Yom Kippur on Mt. Grizim 2016. Note: All pictures were taken by non-Samaritans since Samaritans do not use any form of electricity on Yom Tov. Photo credits Ori Orhof, Modi’in, Israel.

Yom Kippur (the Day of Atonement), which the Israelite-Samaritan community also calls “The Great Day of Atonement” (יום הכפור העצום) and “The Day of Forgiveness and Mercy” (יום הסליחן והרחמים), is one of the Seven Holy Days of the year on the Israelite-Samaritan calendar. The Torah describes it as a day in which the Israelites must afflict (ועניתם) their souls. The Israelite-Samaritan community, like the Jewish community, interprets this phrase as a reference to fasting. In fact, the Samaritan Targum translates ועניתם here as תצימון, “you shall fast.”

The One Fast

In addition to Yom Kippur, Jews keep four fasts to commemorate the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem (this is true of both Rabbinic and Karaite Jews), as well as the fast of Esther. For Israelite-Samaritans, Yom Kippur is the only fast. In fact, we understand Leviticus 16:34 to be an explicit injunction that there can be only one fast a year:

והיתה זאת לכם לחקת עולם לכפר על בני ישראל מכל חטאתם אחת בשנה…

And you shall have this as a permanent statute, to make atonement for the Sons of Yishraael for all their sins once every year…

“And You Shall Teach Your Children (ושננתם לבנך)”

Who is included in the requirement to fast? Deuteronomy 6:7 tells us that we must teach our children the commandments (וְשִׁנַּנְתָּם לְבָנֶיךָ). We understand this to mean that from the moment a child is born, they must keep mitzvot (commandments). For Yom Kippur, this has serious consequences, since it means that children, maybe even babies, need to fast.

This may seem like a very harsh interpretation of the law in this case; shouldn’t religious praxis be more lenient with children? This has been a matter of debate between Jews and Israelite-Samaritans for centuries.

The Jewish Laws of Chinnuch (Education)

From the Jewish perspective, the exemption for children to fast is not really a leniency. Rabbinic Jewish law only requires a person to keep mitzvot from the “age of mitzvah,” 12 for girls and 13 for boys.[1] Rabbinic Jewish tradition understands the education (חינוך) of children to mean that parents must do what they think most proper to ensure that the children will keep mitzvot once they are of age. Moreover, this applies only to children of the “age of education” (around 5 or so), and not at all to toddlers.[2]

And thus, in Jewish practice, small children do not fast at all, and older children only fast for small chunks until they are 10 or 11 and begin “practice fasting.” Upon hearing of the Israelite-Samaritan practice, most (non-Samaritan) Jews react with shock, while the Israelite-Samaritan community finds the Jewish practice of allowing children to eat on Yom Kippur no less shocking.

Kitāb al-Ṭabbākh: Polemic against Jewish “Leniency”

The 11th-century Israelite-Samaritan sage, Abū’l Ḥasan of Tyre (al Ṣūri), in his Arabic Kitāb al-Ṭabbākh (Ṭabbākh for short), defends the Israelite-Samaritan practice in a response to what he perceives as Jewish leniency.

1. The Repeated Reference to “Afflicting the Soul” in the Torah

The Torah notes the requirement for Israelites to afflict themselves (ועניתם נפשתיכם) four separate times.[3] The phrase appears once towards the end of Leviticus 16, after describing the ritual of the two goats, one to God and one to Azazel, and three times in Leviticus 23, a chapter that offers an overview of the rules for Israelite festivals, including Yom Kippur.[4]This repetition reflects the extreme importance the Torah places in this mitzvah.

2. The Threat of Excision (כרת)

To underline the severity of violating this law, the Torah tells us that the punishment for violation is excision:

כג:כט כי כל הנפש אשר לא תענה בעצם היום הזה ונכרתה מעמיה.

23:29 For any soul who will not afflict himself on this same day, he shall be cut off from his people.

In Jewish thinking, this punishment can be applied only to adults age 20 or older,[5] but in Israelite-Samaritan thinking, anyone, even a baby, can receive this punishment.

3. The Meaning of Nefesh

As Abū’l Ḥasan points out in the Ṭabbākh, the term nefesh can have multiple meanings in the Torah.[6] The term is sometimes used to mean all people, even children. For example, the Torah refers to the 70 descendants of Jacob as nefesh:

שמות א:ה ויהיו כל נפש יצאי ירך יעקב שבעים נפש…

Exod 1:5 And all the souls who came from the loins of Yaaqob were seventy souls…[7]

Abū’l Ḥasan argued that to be lenient with children would be risking the excision of their souls. And thus, since the mitzvah of fasting is so significant (1), since it comes with the threat of excision (2), and since nefesh can refer even to children (3), it seems best to be strict.[8]

Suffering Souls and Suffering Children

Israelite-Samaritan tradition has yet another explanation for why children must fast. The fact that children are suffering and crying is a further fulfillment of the phrase ועניתם את נפשתיכם. Feeling hungry and thirsty is bodily suffering, but watching your children cry from hunger, that is “affliction of the soul” (understanding the term literally as the spirit as opposed to the body).

In short, the Israelite-Samaritan view is that children also have souls, and thus, are included in the requirement to suffer on Yom Kippur.[9]

The Exemption for Nursing Babies

For centuries, nursing babies were forced to fast on Yom Kippur, since they were understood to be included in the category of nefesh. This changed with the ruling of the sage, Yizhaq b. Yefet b. Marchiv, popularly known (among Samaritans) as Ab-Hisda of Tyre, in the 12th century CE. He pointed to an early alternative tradition, which claimed that infants should not be required to fast as long as they were still nursing from their fasting mothers, since the milk they consume is itself produced by the fasting mother.

The distinction between nursing infants and other children is expressed clearly in an 18th century Israelite-Samaritan epistle, written by Abraham ben Jacob of the family of Danafta:

אך בעשור לחדש השביעי הזה יום כפורים הוא מקרא קדש יהיה לנו, ובו נעני נפשתינו, כליל זרעינו, מלבד הטף דינק מן אמו. בערב מערב עד ערב נפרש התשבחן למקדשה.

But on the tenth of this seventh month is the day of Atonement, a holy convocation unto us, and on it we afflict our souls, even all our seed, with the exception of the babe that is suckled by its mother, in the evening from the evening until the evening we recite our praises to him that sanctified it. [10]

This has remained the practice in the Israelite-Samaritan community since Ab-Hisda’s decision in the 12th century.

Women and Children in the Synagogue

Yom Kippur is the one occasion of the year when Samaritan women come to synagogue.[11] To some extent, this is so that that can be part of the rituals of this holiest of days, but it is also so that they can help with the hungry children. Before the holiday begins, Israelite-Samaritan parents buy new toys for their children, which help keep them happy for much of the day, but by the afternoon, they are inevitably sick of the toys and, more importantly, hungry and thirsty enough that it is difficult to distract them. Thus, throughout the course of the day, the women of the congregation and their daughters help the younger children to endure the fast, until the arrival of the “reward” at the end of the day, the sumptuous feast.

Twenty-Four Hour Prayer and Study

The fast lasts twenty-four hours, from sunset to sunset (23 hours and 58 minutes to be exact, since the sun sets slightly earlier each day at this time of year). This differs from the Jewish practice of 25 hours, since Jews begin their holy days at sunset but end them only when the stars come out (צאת הכוכבים). (Samaritans do not recognize “stars coming out” as a marker of the day.)

The entirety of the night and day is spent in the synagogue with non-stop services.[12] The only break we ever take from the services is when there is a brit milah (circumcision).

Reading the Whole Torah

In addition to prayers and special hymns (piyyutim) recited on the day, we read the entire Torah in the Qataf form (i.e., chopped up).[13] The Qataf Torah reading is done in what we call the right-left (ימין ושמאל) method, and involves reading the Torah in overlapping groups. The people sitting on the right side of the synagogue, called the Upper People (ימינים) begin reading (as a group) the first passage of the Torah, then the people sitting on the left side, called Lower People (שמאלים), recite the second passage while the first group is still reciting theirs, and so on. This method makes it possible to finish the entire Torah much more quickly than if it were read from beginning to end with no overlapping readers.

The Abisha Scroll

For those observing Yom Kippur on Mount Gerizim, the special Abisha scroll (מכתב אבישע), is brought out. Insofar as content, the Abisha scroll is a standard (Samaritan) Torah scroll; its significance lies in its antiquity. According to Samaritan tradition, the scroll was written by none other than Abisha son of Pinchas son of Elazar son of Aaron, thirteen years after the Israelites entered Canaan.

Not surprisingly, modern scholarship does not confirm this early date, though no firm date has been established. First, the Abisha scroll has never undergone Carbon 14 dating and it likely never will both because the scroll is falling apart and because it is a very holy object from which the kohanim are loathe to tear a piece for chemical dating purposes. Second, the paleographic arguments remain inconclusive. [14]

Some scholars point to scribal notations on the scroll that imply a date of 1065 CE.[15] Other scholars, such as F. Perez Castro and Alan Crown have suggested a 12th century date,[16] but this is very speculative since Perez Castro only succeeded in photographing a fifth of the scroll and Alan Crown never saw actually saw it, since the Israelite-Samaritan kohanim (priests) refused to show it to him. The earliest scholarly dating of the text is Moses Gaster’s (1856-1939) suggestion of a 1st century date; this is also speculative, but he at least did see the scroll.

However one dates it, this ancient Torah scroll is a rare and venerable object, a sacred symbol of tradition and continuity and it is brought out only during holidays.

Shofar Blowing

Yom Kippur services begin and end with the blowing of the shofar. This is based on the commandment in Leviticus 25:9:

והעברת שופר תרועה בחדש השביעי בעשור לחדש ביום הכפורים תעבירו שופר בכל ארצכם.

And you shall sound a ram’s horn abroad on the tenth day of the seventh month, on the day of atonement you shall sound a horn all through your land.

In context, this may be a reference only to the blowing of the shofar on the Jubilee year, but Israelite-Samaritans blow it every Yom Kippur (as do Rabbinic Jews at the end of their services). The shofar blower blows a long blast, as long as his breath holds out, in contrast to the shevarim or teruah type of blast of the Rabbinic Jews. He may also blow multiple blasts if he so wishes.

Erev Yom Kippur and the Final Meal

On the day before Yom Kippur, it is customary for Israelite-Samaritans to visit the graves of their loved ones, and to offer prayers for their souls. (The concept is not very different from the Jewish Yizkor prayers offered in synagogues on Yom Kippur itself.)

A few hours before evening starts, we have the final meal. We avoid salty foods, since this increases thirst, and we drink unsweetened lemonade. The meal is large, but the food is generally not heavy. Traditionally, we serve chicken stuffed with flavored rice, stuffed grape leaves, and light soups. Some prefer a dairy meal, since they believe it is easier to fast after dairy. Some also make sure to eat guavas and sour apples, since they believe it helps with fasting. In short, we have no hard and fast rules for pre-fast foods.

About an hour before sunset, we all meet at the synagogue to “celebrate” each other (לְחַגֵג איש על רעהו). In practical terms, this means we offer each other blessings (as Jews do on Rosh Hashanah). Israelite-Samaritans of the same age give each other a hug and kiss; kissing of the hands is the preferred practice when celebrating an older person, or a kohen or a community leader. After this, the holiday begins and we enter the synagogue.

Break-Fast

When the fast is over, we offer each other the customary blessing for long life:

תנים יומה מאה שנה.

May this day come again for a hundred years.

In other words, may you have another hundred Yom Kippurs. With that, we head home for the breaking of the fast, but we do not jump straight into the meal. Traditionally, before eating the meal, we drink tamarind juice, a sour tropical drink that is also popular among Muslims in their Ramadan break-fasts.

The meal itself is plentiful, but consists only of cold food; cooking is forbidden on Yom Kippur. A standard spread would be salad, stuffed squash, olives, and fruit. For dessert, many like to serve a sour jelly made of apricots and pomegranates.

After the meal, we turn our thoughts away from Yom Kippur and on to the next holiday, Sukkot. And thus it is customary to start preparations for putting up the sukkah after the break-fast meal is over.[17]

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

October 11, 2016

|

Last Updated

March 13, 2024

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Footnotes

Benyamim Tsedaka is the founder and head of the A.B-Institute of Samaritan Studies. He is the editor of A.B. – The Samaritan News Magazine, A Founder of the Society of Samaritan Studies in Paris 1985, the conductor of the Choir of Ancient Israelite Music, and the chairperson of the Samaritan Medal Foundation. Tsedaka has published over 100 articles, essays, and posts on Samaritan Studies. He recently published the firstEnglish translation of the Samaritan Pentateuch.

Essays on Related Topics: