Edit article

Edit articleSeries

A 12th Century Derasha on Parashat Vayishlach: Reconstructing the Speaker’s Notes

A Scholar Seated at a Desk, 1634 Rembrandt National Gallery in Prague. Wikimedia

A Homilist’s Crib Notes

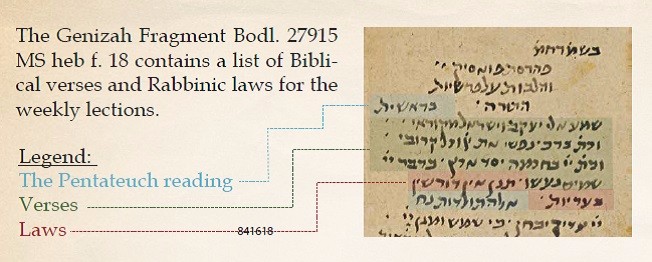

Almost a century ago, a most unusual fragment was discovered at the Cairo Geniza. Rather cryptically, it only consists of a list of 4-8 biblical verses (usually from the Writings and Prophets) and 2-4 primarily mishnaic halakhot for each weekly parasha.[1] The fragment dates to 4872 (=1112 C.E.) according to a colophon, and its title, uniquely comprised of words from three different languages, is quite unusual: פהרסת פואסיק והלכות על פרשיות התורה Fiherst Fawasiq Vahalkhot al Parashiyot Hatorah – A list (Persian) of Verses (Arabic) and Laws on the Lections of the Torah (Hebrew).

What is the nature of this list? An investigation into the list for Parashat Vayishlach provides a test case for solving this apparent mystery. Below is the list:[2]

- Verses from the books of Psalms, Obadiah, and Amos which either refer to king Saul’s pursuit of David or a salvation sent from God.

וישלח יעקב

And Jacob sent

כי מלאכיו יצוה לך

For He will order His angels (Psalms 91:11)

בשלוח שאול

When Saul sent (ibid 59:1)

ישלח ממרום יושיעני[3]

He reached down from high (ibid 18:17)

חזון עובדיה

The vision of Obadiah (Obadiah 1:1)

כאשר ינוס איש

As a man should run (Amos 5:19)

שלח אורך

Send forth your light (Psalms 43:3)

ועלו מושיעים

For liberators shall march up (Obadiah 1:21)

ישלך עזרך מקדש

May He send you help from the sanctuary (Psalms 20:3)

- Dealing with the status of gifts a groom-to-be sends to his future bride in the event that they do not marry

תנן השולח סבלואות לבית חמיו

(m.BB 9:5) It is taught “one who sends presents to the house of his father-in-law”

- Laws concerning one who sets fire to another’s property

ותנן השוליח את הבעירה

(m.BQ 6:4) And it is taught “One who sends a fire”

- The sciatic nerve

ותנן גיד הנשה

(m.Hulin 7:1) And it is taught “the sciatic nerve”

- Practices instituted for maintaining the “ways of peace” (דרכי שלום)

ותנן אילו דברים אמרו מפני דרכי שלום

(m.Gittin 5:8) And it is taught “these are the things they say because of the ways of peace.”

The list contains nine verses from the books of Psalms, Obadiah, and Amos which either refer to king Saul’s pursuit of David or salvation sent from God, and is followed by four mishnaic halakhot from tractates Bava Batra, Bava Kamma,Hulin, and Gittin.

Understanding the Structure of the List: An Outline for a Proem

While the precise meaning of this list of verses and halakhot is unclear, it seems to mirror the structure of proems which open homiletic midrashim, known as petichtaot. A petichta typically begins with a seemingly unrelated biblical verse, followed by midrashic expositions which link this distant, seemingly unrelated verse to the beginning of the parasha in question.[5] The earliest homiletic midrashim from amoraic circles around the 5th century employ verses from נ”ך (Prophets and Writings) alone, while later midrashim from the Tanhuman-Yelamdeinu genre around the 6th-7th century and later open with a halakhic ruling, usually from the Mishnah.

This change in the model of proems reflects a change in the canonical order of the Jewish library. The petichta or proem functions, in part, as a kind of canonical declaration. The distant verse, cited at the beginning, belongs to the secondary canon, whereas the verse aimed at, represents the primary canon—yet both verses belong to the canon.

As the authority of the Mishnah as the secondary Jewish Canon gained strength, the convention of the petichta was reformulated in accordance. The Fihrest Fawasiq Vahalkhot list for Vayishlach comprises both verses from נ”ך and Mishnaic teachings, suggesting that it represents a collection of short-hand notes of openings to be used for a petichta or sermons for each parasha.

Support for the Petichta Notes Theory

A number of texts have been found in the Cairo genizah containing sermons composed primarily in Judeo-Arabic, dating from the 11th-12th centuries, that consist of the same kind of elements enumerated in the list. These texts, however, are full homiletic literary compositions, and hence make the connection between the biblical verses, halakhot and the parasha (or relevant holiday) abundantly clear.

The similarities between these sermons and the list seem to suggest a distinct style of sermons from an Eastern – namely Judeo-Arabic speaking – milieu in the medieval period, and are thus evidence of a lost literary genre. Their common use of Judeo-Arabic indicates they belong to Arabic speaking communities.

But what is the relationship between the different items on the list with each other? Are they independent of one another, implying that the notes offered the homilist different possible openings or directions for a homily on the parasha, or do they together form the skeleton of a single homily?

Decoding the “List” of Biblical Verses of Vayishlach

A careful look at the list of Vayishlach demonstrates that there are several connections between the verses and the halakhot, suggesting that the list represents the skeletons of one complete homily. The immediately apparent connection between them is the presence of the root ש.ל.ח. (“to send”) in the majority of the verses and even in two of the mishnayot cited. This is in line with the opening word of the parasha, וישלח, “and he sent.”[6]

Most of the biblical verses cited are also connected to Parashat Vayishlach in (extant) rabbinic literature, but the following two are not: Ps. 18 ישלח ממרום and Ps. 59, בשלוח שאול. These verses offer another important clue to the purpose of the list.

The Place of Kings Saul and David in a Vayishlach Derasha

Although from different chapters in Psalms, these two verses both refer to Saul, his pursuit of David, and the latter’s escape from him:

Psalms 59:1-4

בשלוח שאול… הצילני מאיבי… הצילני מפעלי און ומאנשי דמים הושיעני… כי הנה ארבו לנפשי

When Saul sent… save me from my enemies… save me from evildoers, deliver me from murderers… for see they lie in wait for me

Psalms 18:1

ביום הציל ה’ אותו מכף כל אויביו וכף שאול

When the Lord had saved him from the hands of all his enemies and from the clutches of Saul.

Saul’s hunting of David is seen as analogous to Esau’s pursuit of Jacob in Vayishlach. Indeed, several Tanhuma-Yelamdeinu midrashim associate the two (Tanhuma [Warsaw] Vayihi 6):

דוד ברח וימלט מפני שאול… וכן יעקב ברח מפני עשו שנאמר ויברח יעקב שדה ארם.[7]

David fled and escaped from Saul… And similarly Jacob fled from before Esau as it is written (Hosh. 12:13) “and Jacob had to flee to the land of Aram.”

The author of the list was likely familiar with traditions associating these two murderous pursuits, and expanded this tradition with additional verses from Psalms which also mention Saul and David.

Intertextual Reading: Linguistic Connections between the Verses

The collection of verses also demonstrates a sensitive intertextual reading of the Hebrew Bible, attuned to the textual similarities between the various verses describing Saul’s pursuit of David and Esau’s pursuit of Jacob. Despite being culled from different places throughout the Hebrew Bible, the verses share a number of analogous linguistic features.

“Distress” (צ.ר.ה)

For example, the root צ.ר.ה appears twice in Vayishlach (Gen 35:3) “who answered me when I was in distress” (העונה אותי ביום צרתי) and (32:8) “Jacob was greatly afraid and distressed” (ויירא יעקב מאד ויצר לו), and is likewise found in several of the verses/chapters of Psalms on the list:

- Ps 18:7 states: “In my distress I called out” (בצר לי אקרא)

- Ps 59:17: “a refuge in time of trouble” (ומנוס ביום צר לי),

- Ps 20:2: “may the Lord answer you in time of trouble” (יענך י-הוה ביום צרה).

The latter verse is associated with Vayishlach in classical rabbinic literature,[8] which indicates that the homilist of the list followed in this aggadic tradition and expanded on it, by adding two additional verses from Psalms. צרה similarly appears in the Book of Obadiah (verse 12), from which two other verses included in the list on Vayishlach are drawn.[9]

“Save” (נ.צ.ל)

The root נ.צ.ל, “to save” likewise appears in Vayishlach; Jacob entreats God to “save me from my brother” (הצילני נא מיד אחי) (Gen 32:12):

- Psalm 18:1 “on the day he saved” [10] (ביום הציל),

- 59:2 “save me” (הצילני),

- 91:3, (from which psalm another verse is included on the list) “that He will save you (כי הוא יצילך).”

The shared use of these words along with other repeated words such as ביום, אויב, קרא also tie these various texts from the Hebrew Bible together.

Reconstructing the Theme of the Sermon

The text from the Geniza thus represents a group of verses that were carefully chosen and collated to create a unified composition, centering on Esau’s pursuit of Jacob and its comparison to Saul’s similar pursuit of David. Is there any way to uncover the possible content of the homily as well?

Comparison with Homily from Pesikta Rabbati

An earlier midrash, which likewise associates the pursuits of Jacob and David, may offer insight into the larger message of this homiletic proem. While this midrash appears in several midrashic works, the version in the Tanhuma-style work, Pesikta Rabbati, bears the most resemblance to the theme of our list.[11] This midrashic tradition explicates the underlying connection between the pursuits of Jacob and David, tying them both into a passage from Ecclesiastes (3:15) “God seeks the pursued.”[12]

והאלהים יבקש את נרדף לעולם הקדוש ברוך הוא אוהב (אני) את הנרדפים ושונא (אני) את הרודפים …

והאלהים יבקש את נרדף לעולם הקדוש ברוך הוא אוהב (אני) את הנרדפים ושונא (אני) את הרודפים …

“God seeks the pursued” (Eccl. 3:15) – God always loves those who are pursued, and despises those who pursue…

כך עשו רודף אחר יעקב על רדפו בחרב אחיו ושחת רחמיו (עמוס א’ י”א) אמר הקדוש ברוך הוא אוהב אני לנרדף ושונא לרודף ואת עשו שנאתי (מלאכי א’ ג’) אבל יעקב ואוהב את יעקב (שם שם /מלאכי א’/ ב’), למה, והאלהים יבקש את נרדף

So did Esau pursue Jacob, “because he pursued his brother with the sword and repressed all pity” (Amos 1:11), [therefore] God said “I love the pursued and reject the pursuer ‘I have rejected Esau’ (Malachi 1:3) but as for Jacob, ‘I have loved Jacob (ibid 1:2).’” Why? “God seeks the pursued.”

דוד נרדף ושאול רודף אמר הקדוש ברוך הוא אוהב אני לנרדף ושונא אני לרודף קרע ה’ את הממלכה ונתנה לרעך (שמואל א’ ט”ו כ”ח) לדוד והאלהים יבקש את נרדף…[13]

David was pursued and Saul pursued. The Holy One blessed be He said: “I love the pursued and despise the pursuer ‘the Lord has torn the kingship (of Israel away from you…) and has given it to your fellow…’ (Samuel 1 15:28) to David.” ‘God seeks the pursued’

The troubles shared by David and Jacob are understood as reflecting the theological principle articulated in Ecclesiastes that God takes care of and loves those who are persecuted. The author of this list made use of this connection to develop a complete homily.

Understanding the Connection with the Halakhot

But how do the halakhot connect to this homily?

The Root ש.ל.ח

On a simple level, they are connected by the use of the root ש.ל.ח. in the first two mishnayot. The law of גיד הנשה (the sciatic nerve) appears in this parasha and, perhaps relatedly, includes the root ש.ל.ח. in the narrative surrounding it (Gen 32:27):

וַיֹּאמֶר שַׁלְּחֵנִי כִּי עָלָה הַשָּׁחַר וַיֹּאמֶר לֹא אֲשַׁלֵּחֲךָ כִּי אִם בֵּרַכְתָּנִי:

(The man) said, “Let me go, for it is daybreak.” (Jacob) replied, “I will not let you go unless you bless me.”

Allusions to the Story of Jacob and Esau’s Meeting

But the mishnayot may also relate in a more meaningful way to the homily concerning Esau’s pursuit of Jacob.

- Sending gifts (השולח סבלואות) – The image of a man sending gifts to his future bride at her father’s house is reminiscent of Jacob’s sending gifts to Esau, which takes up a large part of the opening section of the parasha (Gen 32:4-22).

- One who sends fire (השולח את הבערה) – The law regarding tort damage caused by fire may signify Jacob struggle’s with Esau through the image of the fire sent to Edom in the vision of Obadiah (verse 18), regarding the struggle between Israel and Edom:

וְהָיָה בֵית יַעֲקֹב אֵשׁ וּבֵית יוֹסֵף לֶהָבָה וּבֵית עֵשָׂו לְקַשׁ וְדָלְקוּ בָהֶם וַאֲכָלוּם…

The House of Jacob shall be fire, and the House of Joseph flame, and the House of Esau shall be straw; they shall burn it and devour it…

Indeed, earlier rabbinic traditions associate rulings regarding damages caused by fire with biblical passages describing the persecution of the Jewish people.[14]

- The law pertaining to the sciatic nerve[15] – This may also contribute to the theme of the homily: the angel who struggles with Jacob and dislocates his sciatic nerve is identified in a number of rabbinic traditions as the ministering angel of Esau.[16]

- Because of the ways of peace (מפני דרכי שלום) – This concept correlates with Jacob’s attempts to establish peace with Esau, and a lost Yelamdeinu passage on Gen 32:5 preserved in Yalkut Talmud Torah (p. 90),[17] makes this connection explicitly:

ד”א א”ל הב”ה ליעקב: לא דייך שעשית את הקדש חול, אלא שאני אמרתי ורב יעבד צעיר (בר’ כ”ה, כ”ג), ואתה אמרת עבדך יעקב, חייך כדברך כן יהיה, הוא ימשול בך בעולם הזה ואתה תמשול בו לעולם הבא. אמר לפניו: רבון כל העולמים, אני מחניף לרשע בשביל שלא יהרגני. מכאן אמרו: מחניפין לרשעים מפני דרכי שלום.[18]

Alternatively,[19] the Holy One blessed be He said to Jacob: “Is it insufficient for you that you made the holy profane? For I had said ‘and the older shall serve the younger,’ and you now say ‘your servant Jacob’? I swear that as you have said, so it will be; he will rule you in this world, and you will rule him in the world to come.” [Jacob] responded: “Master of the universe, I [only] flattered the wicked one so that he would not kill me.” From here they say, flatter the wicked because of the ways of peace.[20]

The Persistence of Midrashic Method

The exegesis of the medieval period is typically described as moving away from the homilies of classical rabbinic literature toward grammatical and rational concerns, following R. Saadyah Gaon.[21] An investigation of this 12th century homilist’s list, however, reveals the extent to which midrash aggadah continued to persist and be a driving force behind the interpretation of Torah.

The reconstruction of the homily to Vayishlach demonstrates the exegetical methods underlying the list of verses and mishnayot: linguistic analogies, intertextual reading of scripture, and the use of existing midrashic traditions and verses associated with Vayishlach. It further demonstrates how midrashic traditions were expanded in a living fashion, even in this later period, through employing midrashic and aggadic methods and other biblical verses and rabbinic rulings.

A Sermon from Notes on the Persecution of Jews

At the same time, it offers a window into the practices of a preacher from the medieval period, who rather than writing out the full text of a sermon, utilized a system of short-hand notes from which he presumably drew. In the case of Vayishlach, he seems to have constructed a sermon that drew from classical midrashic form, and centered on Jacob and Esau’s struggle as representative of God’s protection of the oppressed.

While it is unknown whether the audience of this sermon saw itself as victims of persecution, this message would certainly have broader resonance than the one-time occurrence of Jacob and Esau’s personal struggle. In this way, the author of this homily has rendered the biblical account timeless.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

December 14, 2016

|

Last Updated

January 4, 2024

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Footnotes

Dr. Moshe Lavee is a lecturer in Talmud and Midrash and chair of the Inter-disciplinary Centre for Genizah Research in The University of Haifa. His research expertise is in Aggadic Midrash, especially in the communities of the Genizah. Moshe runs programs for young leadership and educators (“Mashavah Techila” and “Ruach Carmel”), working to foster relationships between the academic world and the larger community.

Dr. Oded Rosenblum is a member of The Center for Inter-disciplinary Research of the Cairo Genizah at Haifa University. He holds a Ph.D. in Talmud from Haifa University’s Jewish History department. Rosenblum is a member of several research groups dealing with Talmudic literature.

Dr. Shana Strauch-Schick is a post-doctoral fellow at The Center for Inter-disciplinary Research of the Cairo Genizah at Haifa University. She received a Ph.D. in Talmudic Literature from Revel at Yeshiva University where she also completed an M.A. in Bible. Her publications include, “The Middle Persian Context of the Bavli’s Beruriah Narratives,” Zion 79.3 [Hebrew].

Essays on Related Topics: