Edit article

Edit articleSeries

Symposium

Ancient Egyptian Clothing: Real and Ideal

Tomb of Pashedu Deir el-Medina Pashedu, dated to the early years of Ramesses II. kairoinfo4u / Flickr

In big-screen epics about Egypt, the costuming lets the audience know the setting. Throughout the twentieth century, people were fascinated by the minutia of daily life in ancient Egypt, with a subgenre of popular texts documenting how mundane existence in Egypt was not so different from that of our own in the modern West.

Israelites Borrowing Egyptian Clothing

As part of the exodus story, the Torah describes the Israelites borrowing clothing and jewelry from their neighbors:

שמות יא:א וַיֹּ֨אמֶר יְ-הֹוָ֜ה אֶל־מֹשֶׁ֗ה... יא:ב דַּבֶּר נָ֖א בְּאָזְנֵ֣י הָעָ֑ם וְיִשְׁאֲל֞וּ אִ֣ישׁ׀ מֵאֵ֣ת רֵעֵ֗הוּ וְאִשָּׁה֙ מֵאֵ֣ת רְעוּתָ֔הּ כְּלֵי כֶ֖סֶף וּכְלֵ֥י זָהָֽב:

Exod 11:1 And Yhwh said to Moses… 11:2 Tell the people to borrow, each man from his neighbor and each woman from hers, objects of silver and gold.”

שמות יב:לה וּבְנֵי יִשְׂרָאֵ֥ל עָשׂ֖וּ כִּדְבַ֣ר מֹשֶׁ֑ה וַֽיִּשְׁאֲלוּ֙ מִמִּצְרַ֔יִם כְּלֵי כֶ֛סֶף וּכְלֵ֥י זָהָ֖ב וּשְׂמָלֹֽת: יב:לו וַֽי-הֹוָ֞ה נָתַ֨ן אֶת חֵ֥ן הָעָ֛ם בְּעֵינֵ֥י מִצְרַ֖יִם וַיַּשְׁאִל֑וּם וַֽיְנַצְּל֖וּ אֶת מִצְרָֽיִם:

Exod 12:35 The Israelites had done Moses’ bidding and borrowed from the Egyptians objects of silver and gold, and clothing. 12:36 And Yhwh had disposed the Egyptians favorably toward the people, and they let them have their request; thus they stripped the Egyptians.

When reading this, it’s natural to wonder what the Israelites might have borrowed—what did the ancient Egyptians wear, particularly during the New Kingdom period of roughly 1550-1070 BCE and into the following Third Intermediate Period? As with many questions in the study of Egypt, the archaeological evidence supports one answer, while the popular perception of ancient Egypt suggests another.

The major sources for information on clothing are:

- Surviving laundry lists of items taken to be washed.

- The contents of elite tombs.

- Art

Clothing as Depicted in Art

Both popular, modern sources and scholarship on Egyptian society have traditionally drawn heavily on the art of the period. The lush and colorful wall paintings of the Theban tombs and the sculpture of royal monuments show Egypt not as it was, though, but as the Egyptian one-percenters wished to communicate it, as an idealistic expression of their own status.

This is common across all periods and societies, however. Whenever patrons commission art, their own self-image is a concern of the artist. Even the supposedly “realistic” portraiture of ancient Rome is highly stylized, while today we take dozens of selfies and use filters or enhance using Photoshop in order to be seen as we wish.

Even with this caveat, it’s important to remember that Ancient Egyptian art does not employ realism as we understand it. Due to their use of the “aspective,” a focus on the most important view of a subject, Egyptian people are seen with distorted proportions that do not add up to a realistic human form. Information about what the Egyptians wore has to be extracted, carefully, from the art.

The King and Queen

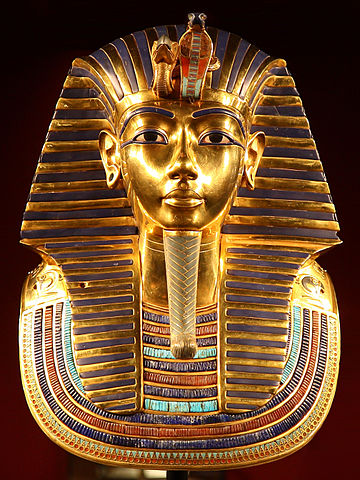

The king and queen are identifiable in artwork by their attributes of office, particularly crowns and scepters. They are always marked out by a uraeus, the protective curled cobra, on the brow. Kings, including female kings, are seen wearing the red and white crowns that symbolize Lower and Upper Egypt, respectively. A combined dual crown symbolizes the unity of Egypt in the person of the ruler.In the New Kingdom, the khepresh becomes very popular; this is a blue, helmet-like crown which might indicate the political and state functions of the ruler, as opposed to religious ones. Other examples of headgear include diadems and the well-known nemes, the blue-and-gold striped head cloth. The nemes is often erroneously depicted on non-royal Egyptians in modern, popular representations of Egypt, but it was solely worn by the king. Queens, meanwhile, wore fillets and the ostentatious vulture headdress.

Elite Clothing

The clothing of elite non-royal Egyptians is similar to that of the king and queen, absent the symbols of royalty. New Kingdom art, especially that of the eighteen dynasty, also shows new trends in dress and costume.

Male attire: Elite men had always been shown in ancient Egyptian art wearing kilts, shorter in youth and longer on older men. From the reign of Akhenaten around 1330 BCE, men’s torsos were sometimes shown covered. Some priests wear leopard skins or have visibly shaved heads. Generally, men’s dress was non-restrictive and probably reflected their active social role.

Female attire: In contrast, depictions of elite women emphasized their role in reproduction and the life cycle. Prior to the New Kingdom, wealthy women were shown wearing sheath dresses so tight on the body that they revealed the thighs, buttocks, pubic area and, often, one breast. In the eighteenth dynasty, these tight, restrictive dresses gave way to billowing, diaphanous, pleated dresses and robes.Through these garments and under increasingly elaborate wigs, the outline of the body often remains visible, emphasizing the sexual function of women in Egyptian society. These complicated fashions communicate that the wearer is wealthy enough to both afford high-quality clothing a-la-mode and need not perform work which wasn’t permitted by such clothing.

Non-Elite Clothing

In most depictions of labor in the eighteenth-dynasty tombs, male workers are rarely naked but often scantily clothed, the men stripped down to loincloths and their overseers more dressed. Serving girls of all kinds were depicted naked, sometimes with emphasis on the pubic area, yet there is no male analogue. Children of both genders and all classes, meanwhile, were almost always shown naked. It’s important to remember that these were images of non-elites and children as privileged adults wanted to see them for the purpose of expressing their own self-perceptions. This doesn’t mean such images are inaccurate per se, but does indicate care in interpretation.

Clothing: The Archaeological Record

As for what the ancient Egyptians actually wore in this period, the answer might disappoint. The climate in Egypt was hot in summer, cold in winter, dry and sandy in the Nile Valley, and humid and muddy in the Delta. Most Egyptians performed menial labor for a living and would have had to dress for it. In the eighteenth dynasty, c. 1550-1300, tomb contents mirrored the “daily life” scenes on the walls, and clothing is among the finds in intact tombs from this period. Textiles are organic fibers and particularly prone to deterioration, thus the sample of surviving evidence is small and skewed, especially compared to artistic interpretations.

Even these surviving garments are comparatively boring. Egyptian men and women wore baggy tunic-like garments. Women sometimes wore detachable bodices and sleeves. Descriptions of clothing on itemized legal documents can be very general, including vague-sounding cloaks, sheets, and loincloths of thin and/or fine cloth.

In villages of lower elites such as Deir el-Medina, the weaving of many of these garments was probably done by women of the household on an upright loom. It was likely that the act of making these cloths was more important than how they were worn, as evidenced by the meticulous packing of linens in chests in New Kingdom tombs.[1]

The predominant footwear was the sandal; there were several styles ranging in material from woven reeds to leather. Pharaoh’s footwear, although also a sandal, was of much greater quality. Tutankhamun, for instance, had a leather pair with caricature depictions of Egypt’s enemies bound on the insole; when the king walked he could magically crush his nemeses.[2] Tut and his successors buried in a group tomb in the Delta, c. 1000-850 BCE, were shod in sandals of gold, though this is likely for ritual purposes and not something worn in life.

Myth and Reality in Egypt

Given the golden splendor from Tut’s tomb, and the idyllic scenes of wealth painted in elite tombs, it is easy to imagine the ancient Egyptians dressed fabulously in luxurious materials. Yet that Egypt is more myth than fact. We can’t shoulder all of the blame for this; the Egyptians wanted to be remembered this way.

It is tempting to envision an envoy like Moses treating with the king, seated in a kiosk and dressed in finery like Amenhotep III as shown in the tombs of his courtiers. Yet attempts to recreate such a scene from artistic sources would never be entirely accurate. Even the mudbrick palaces in which such meetings would have occurred have long since deteriorated.

Most likely, the realities of daily life meant that most Egyptians dressed mostly in utilitarian garb fitted to their daily activities in the climate they inhabited – as have all people throughout history. Yet if the visual record the Egyptians left us has inspired glorious fantasies about their civilization, why we entertain such fantasies says as much about us as it does about them.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

April 18, 2016

|

Last Updated

January 3, 2026

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Dr. Rachel P. Kreiter earned a doctorate in art history from Emory University in December 2015 and has written about arts and culture for various publications, including Burnaway and the Awl. Their research interests include ancient Egypt in its myriad contexts, including the African continent, ancient Near East, contemporary art, and museums.

Essays on Related Topics: