Edit article

Edit articleSeries

A Shofar-less Rosh Hashanah: A Karaite’s Experience of Yom Teru’ah

Torah scrolls in the Karaite Jewish synagogue, Congregation B’nai Israel, in Daly City California.

It is so, that for most of the appointed times, there is a reason for their being required; either because they are a remembrance for a certain miracle or a certain event. However, in the case of Yom Teru’ah the reason is not evident from the biblical text. – Adderet Eliyahu (Introduction to the Section on Yom Teru’ah, p. 44b).[1]

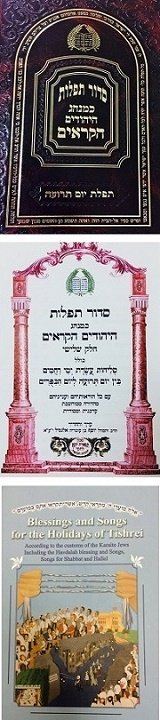

For most Jews, Rosh Hashanah is synonymous with the blowing of the shofar. But I have never actually heard the shofar blown at my Karaite Jewish synagogue. By way of background, my family comes from the historical Karaite Jewish community in Egypt, and I attend Congregation B’nai Israel, the only free-standing Karaite Jewish synagogue in the Western Hemisphere, located just south of San Francisco in Daly City, California.

Among the historical divides between Karaites and Rabbanites concerns whether we are commanded to blow the shofar on Yom Teru’ah, the day most Jews refer to as Rosh Hashanah.[2] Quite simply, the Karaite view is that no such commandment exists.

A Day of Trumpeting or a Day of Shouting?

The phrase “Yom Teru’ah” is generally interpreted by Karaites as “Day of Shouting,” as in “shouting in prayer.” This understanding is consistent with the usage of the word teru’ah in Joshua 6:5 in which the people are told to “shout a great shout.”[3]

While Karaites interpret “Yom Teru’ah” as a “Day of Shouting;” the word “teru’ah” may also refer to a trumpeting sound as it does with respect to the sounding of silver trumpets. (See Numbers 10:5-6.) And the Torah specifically commands us to sound (“teru’ah”) the shofar on Yom Kippur to announce the Jubilee year (Leviticus 25:9). Thus, it is conceivable that Yom Teru’ah is intended to be celebrated by the sound of the shofar.

Moreover, according to historians, a minority of Karaites in Byzantium did not oppose the blowing of the shofar on Yom Teru’ah.[4] Nevertheless, traditionally speaking, the majority opinion of Karaite communities is that there is no commandment to blow the shofar, especially given that the Torah never mentions a shofar in the verses concerning Yom Teru’ah.

Blowing Shofar as a Form of Melacha (forbidden work)

Another important reason that Karaites have historically not blown the shofar on Yom Teru’ah is that traditional Karaite halacha deems playing instruments – including blowing the shofar – to be an act of melachah—forbidden labor of the sort prohibited on Shabbat and Yom Tov. Yom Teru’ah is a day on which the Torah says that melechet avodah is forbidden (see Leviticus 23:23-25), and the majority of Karaites deem that prohibition to encompass blowing of the shofar.[5] For example, the 11th century Karaite scholar, Jacob Ben Reuben, wrote in his Sefer ha-Osher that one reason the majority of Karaites do not blow the shofar is “so that they will not profane the holiday.”[6]

The Theme of Yom Teru’ah and the Torah Reading

The Torah does not tell us the reason why we are commanded to observe Yom Teru’ah; but given its proximity to Yom Kippur (the holiest day of the year) and Sukkot (an important agricultural festival), the holiday serves as a national day of awakening to prepare for the upcoming holidays. The Karaite liturgy, as well as zemirot composed for Yom Teru’ah, reflect that Yom Teru’ah is a day of teshuvah (repentance).[7] By way of illustration, the Karaite Zerach ben Natan of Troki composed a hymn whose opening words and refrain are “zeh yom rishon el ha-tshuvah” or “this is the first day for repentance.”

The theme of teshuvah is also reflected in Parashat Kedoshim, the Torah portion Karaites read on Yom Teru’ah. We remind ourselves to act in a holy manner, to remember the Sabbath, to provide for the poor and to treat others with compassion. These themes lead in to Yom Kippur, our national day of atonement. Kedoshim also discusses the importance of leaving the corners of our fields for the poor, an indirect reminder before the agricultural holiday of Sukkot.

As with the Rabbanite community, Karaites – at least those of the last few centuries – also walk the line between observing this day as the beginning of a period of repentance and a day of joy. For example, the author of The Karaite Jews of Egypt informs us that the Karaite community of Egypt viewed the day as one of celebration, prayer and rest. Historically, Karaites did not have special Yom Teru’ah foods – no apples and honey, etc. – but the community does enjoy a festive meal after services. The foods include traditional Egyptian Karaite dishes, which may be cooked on the holiday.

Aseret Yemei Rachamim

Yom Teru’ah also kicks off the Aseret Yemei Rachamim, a ten-day period leading up to Yom Kippur during which we seek mercy from God (roughly parallel to the Rabbinic Aseret Yemei Teshuvah, Ten Days of Repentance).

Traditionally, the Karaites of Egypt did not engage in sexual relations during these ten days.[8] It was also a period of time during which the community arrived at the synagogue well-before sunrise to recite selichot (or penitential prayers). This practice continues to this day in more concentrated Karaite communities – especially in Israel, and parallels the Rabbinic Jewish practice of early morning selichot on these days.

The Karaite Calendar

Unlike Rabbinic Jews, Karaite Jews have not had a fixed calendar historically. Observant Karaites continue the ancient practice of setting our months by physically going out and observing the crescent new moon.[9] This means that our Yom Teru’ah might fall on a different day from Rosh Hashanah as calculated by the Rabbinic calendar.[10]

Furthermore, even in the Diaspora, Karaites only observe one day of Yom Teru’ah. In fact, we do not add an additional day to any of our holidays in the Diaspora. This is because the majority view of Karaites throughout history has been that the local moon (as opposed to the moon in Jerusalem or the Land of Israel) is what determines the start of the months. As a result, Karaites generally do not believe it necessary to add a day to our holidays in order to coordinate our observance with the Land of Israel. Additionally, as Scripturalists, Karaites are reluctant deviate from the lengths prescribed for the mo’adim. In this regard, even those Karaites in the Diaspora today who believe that we should follow the new moon from the Land of Israel do not add an additional day to their moadim.[11]

On this last point, the historians record a rather peculiar incident in which the 10th Century Karaite exegete Jacob al-Kirkisani asked one of the students of Sa’adyah Gaon why many Rabbanites would not marry the Karaites, but would marry the Issawites, adherents to a 7th Century messianic leader. The answer, as Kirkisani recorded it and has been interpreted by leading historians, was that the Rabbanites would marry the Issawites because the Issawites also keep Yom Tov Sheni, the additional day for the holidays outside of Israel.[12]

Maintaining a Karaite Identity

I find that maintaining an identity as a Karaite Jewish minority in a Jewish world dominated by Rabbinic tradition is increasingly difficult. Although over the last centuries Rabbinic notions of Rosh Hashanah have crept into the Karaite understanding of Yom Teruah, the shofar has not.

The sound of the shofar is beautiful, and I love what it represents for the Rabbanite world. It just does not carry the same significance for me and other historical Karaites. Throughout the Middle Ages, the Karaites and Rabbanites polemicized vigorously over whether we are commanded to blow a shofar on Yom Teru’ah/Rosh Hashanah. I prefer to leave polemics in the Middle Ages, and I pray that this piece shed a little light on the Karaite approach to text and tradition.

Whether you are celebrating Yom Teru’ah or Rosh Hashanah, one day or two days, blowing the shofar or not, I wish you a mo’ed shalom.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

September 18, 2014

|

Last Updated

September 28, 2024

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Footnotes

Shawn Joe Lichaa is the founder of A Blue Thread, A Jewish Blog with a Thread of Karaite Throughout (ABlueThread.com), and a co-author of As it is Written: A Brief Case for Karaism. He has spoken about Karaite Judaism at many venues, including synagogues, Jewish day schools, the Library of Congress, and the Association of Jewish Libraries.

Essays on Related Topics: