Edit article

Edit articleSeries

I (God) and Not an Angel: The Haggadah Counters Jesus and the Arma Christi

Passover Haggadah according to the Romanian rite, decorated with paintings of Italian origin, folio 10v & 11r. Copied by Matthias Spagnolo for Leon Bilo bar Yuda in 1583. Bibliothèque nationale de France.

At its core, the Passover Haggadah is a midrashic commentary on a few verses in Deuteronomy, a summary version of the Exodus story declared when bringing the first fruits (Deut 26:5–8).[1] The last verse of the passage reads:

דברים כו:ח וַיּוֹצִאֵנוּ יְ־הוָה מִמִּצְרַיִם בְּיָד חֲזָקָה וּבִזְרֹעַ נְטוּיָה וּבְמֹרָא גָּדֹל וּבְאֹתוֹת וּבְמֹפְתִים.

Deut 26:8 And YHWH brought us out of Egypt with a mighty hand and an outstretched arm, with great terror, and with signs and wonders.”

In one of its interpretations of this verse, the Haggadah comments:

וַיּוֹצִאֵנוּ ה' מִמִּצְרַיִם. לֹא עַל יְדֵי מַלְאָךְ, וְלֹא עַל יְדֵי שָׂרָף, וְלֹא עַל יְדֵי שָׁלִיחַ, אֶלָּא הַקָּדוֹשׁ בָּרוּךְ הוּא בִּכְבוֹדוֹ וּבְעַצְמוֹ.

The Lord brought us out of Egypt. Not by an angel, not by a seraph, not by a messenger but rather by the Holy One blessed be he through his own glory and his own power.

The Haggadah then supports its interpretation by citing God’s first-person prediction of the final plague:

שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר: וְעָבַרְתִּי בְאֶרֶץ מִצְרַיִם בַּלַּיְלָה הַזֶּה, וְהִכֵּיתִי כָל בְּכוֹר בְּאֶרֶץ מִצְרַיִם מֵאָדָם וְעַד בְּהֵמָה, וּבְכָל אֱלֹהֵי מִצְרַיִם אֶעֱשֶׂה שְׁפָטִים, אֲנִי ה'.

As it says [in Exodus 12:12]: “I will pass through Egypt on this night, I will strike down the firstborn in the land of Egypt both humans and animals, and against all the gods of Egypt I will render judgments; I am the Lord.”

The Haggadah expands on each section of this verse:

וְעָבַרְתִּי בְאֶרֶץ מִצְרַיִם בַּלַּיְלָה הַזֶּה – אֲנִי וְלֹא מַלְאָךְ.

I will pass through Egypt on this night. [This means] I and not an angel.

וְהִכֵּיתִי כָל בְּכוֹר בְּאֶרֶץ מִצְרַים. אֲנִי וְלֹא שָׂרָף.

I will strike down the firstborn in the land of Egypt. [This means] I and not a seraph.

וּבְכָל אֱלֹהֵי מִצְרַיִם אֶעֱשֶׂה שְׁפָטִים. אֲנִי וְלֹא הַשָּׁלִיחַ.

Against all the gods of Egypt I will render judgments. [This means] I and not a messenger.

אֲנִי ה'. אֲנִי הוּא וְלֹא אַחֵר.

I am the Lord. [This means] I and no one else.

Some scholars view this interpretation as a response to a Gnostic belief that a divine logos (a personified Wisdom) helped God to redeem the Israelites. However, it is more likely a response to Christianity and its claim that God redeemed humanity through a messianic Jesus.[2] No, this midrash retorts, God did not rely on an intermediary. Israel’s redemption was far greater than the redemption conceived by Christians, because God intervened directly to save his people.

The Midrash Continues

Where we might expect the Haggadah to continue directly with a recitation of the biblical plagues to enumerate God’s actions, it instead lists five items:[3]

בְּיָד חֲזָקָה. זוֹ הַדֶּבֶר

With a mighty hand. This is pestilence.[4]

וּבִזְרֹעַ נְטוּיָה. זוֹ הַחֶרֶב

And with an outstretched arm. This is the sword.[5]

וּבְמוֹרָא גָּדֹל. זוֹ גִלּוּי שְׁכִינָה

And with great terror. This is the revelation of the Shechinah.[6]

וּבְאֹתוֹת. זֶה הַמַּטֶּה

And with signs. This is the staff.[7]

וּבְמֹפְתִים. זֶה הַדָּם

And with wonders. This is the blood.[8]

The pestilence is drawn from the Exodus story of the plagues and refers to the cattle disease of the fifth plague (9:3), while the staff refers to the staff that Moses uses to work some of the plagues (e.g., 7:17, 8:1). There is no mention in Exodus, however, of God using a sword to strike the Egyptians or revealing the Shekhinah. Why does the Haggadah include this?[9]

Just as the first part of the Haggadah’s midrash counters the Christian understanding of redemption—God did not need an assistant (like Jesus) to save his people; he and no one else delivered them—so this second part extends the anti-Christian polemic, countering a tradition known as the Arma Christi, “the weapons of Christ,” with its own catalogue of the powers that God used to deliver Israel from slavery and death.

The Arma Christi

In the Arma Christi tradition, the implements that were used against Jesus during the Crucifixion,[10] such as the Cross itself, the crown of thorns, the lance used to pierce Jesus’ body, and the nails driven into his hands and feet have paradoxically been transformed into the weapons by which Jesus achieved victory over his enemies on humanity’s behalf.[11]

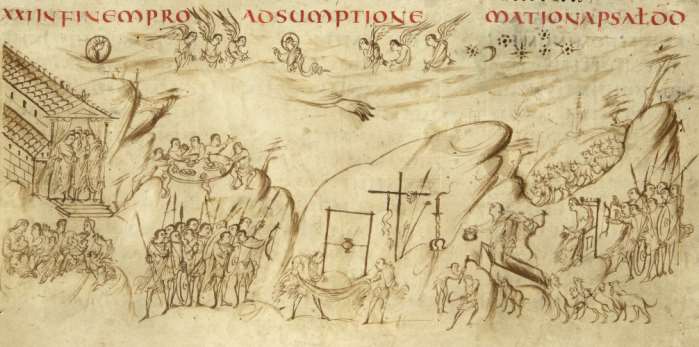

The Utrecht Psalter

The full Arma Christi tradition only became a popular theme in European Catholicism after the 13th century,[12] but an early version appears in the Utrecht Psalter’s (9th century) illustration of Psalm 21 [MT Ps 22], a celebration of God’s victory over his enemies that in Christian tradition is read as a prophecy of the Crucifixion:[13]

The Utrecht Psalter does not explicitly label the items shown—including the Cross, the lance, and the crown of thorns that was placed on Jesus’ head—as weapons, but it suggests as much by positioning them between two groups of armed soldiers on a battlefield and presents them as the trophies of a military victory assembled together for display.[14]

A similar tradition is found in the Greek-speaking Byzantine Empire, which ruled Palestine until its conquest by Muslims in the 7th century and continued to influence religious life there beyond that. A sermon by Photius (820–893), a 9th century patriarch of Constantinople, celebrates the implements of the Crucifixion, including the nails driven into Jesus’ hands, the crown of thorns, and the lance.[15]

The Midrash and the Arma Christi

Though its precise origins are unknown, manuscript evidence indicates that the Haggadah’s midrash on Deuteronomy 26:8 in its present form existed by the 9th or 10th century.[16] It may have developed in Palestine under Byzantine rule prior to the 630s or under the influence of Byzantine culture thereafter. Thus, the author of the midrash may have encountered one of the precursor versions of the Arma Christi tradition.[17]

Read in this light, the instruments that God used to secure the redemption of Israel each has a counterpart in the Arma Christi tradition:[18]

The hand of the Lord. The connection to dever (pestilence) in the Haggadah’s midrash derives from Exodus’ account of the fifth plague (Exod 9:3). In the illustration from Utrecht Psalter, the hand of the Lord itself reaches out from heaven toward the Cross.[19] Later European depictions also include disembodied hands—the hand of a Jew striking Jesus or clutching his hair, symbols of the role of Jews in mocking and torturing Christ—among the weapons instrumental in Christ’s victory.[20]

The sword, presumably of God, is the only literal weapon in the Haggadah’s catalogue. No sword is mentioned in the biblical account in Exodus, but its inclusion in the midrash likely draws on a biblical association of pestilence with God’s sword. Amos, for example, places the two terms in apposition to one another:

עמוס ד:י שִׁלַּחְתִּי בָכֶם דֶּבֶר בְּדֶרֶךְ מִצְרַיִם הָרַגְתִּי בַחֶרֶב בַּחוּרֵיכֶם....

Amos 4:10 I have sent a pestilence against you in the way of Egypt and I have killed with a sword your young men.

The sword also has a counterpart in the Arma Christi tradition. In the Utrecht Psalter illustration, the closest analog is one of the other objects used to strike Jesus—the lance or the scourge—and later depictions of the Arma Christi tradition actually include swords, such as the one that Peter used to cut off the ear of the servant sent to arrest Jesus (Matt 26:51, Mark 14:47, Luke 22:50).

Since the pestilence and the sword come from the earlier midrash found in Sifrei to Numbers, it might only be a coincidence that they have counterparts in the Arma Christi. The Haggadah’s addition of three other items that correspond to the Arma Christi, however, makes clear that the expansion of the earlier midrash mirrors items associated with redemption in Christian tradition.

The Shechinah refers to an aspect of God that settles down and dwells on earth, and it was imagined in rabbinic sources as a protective presence of God that was revealed to Moses and the Israelites during the Exodus, much like the biblical kavod (often transalted as “glory”; see, e.g., Exod 24:16–17; 40:34–35).[21] Christianity developed a similar idea in the form of the Holy Spirit, conceived as an agent of revelation and also as a protective presence that revealed itself during the Crucifixion.[22] It is often depicted as a dove. For example, an 11th-century Byzantine image from the Pala d’Oro in Venice presents a dove together with the Cross, the crown of thorns, the lance, and the sponge, and in later European depictions of the Arma Christi, a dove rests on top of the Cross.[23]

The staff. The Haggadah interprets the word “signs” as referring to the staff that Moses used to perform signs and wonders. Its counterpart in the Arma Christi is the Cross. A widely circulated medieval legend traced the staff’s history from its origin in the Tree of Life in the Garden of Eden (Gen 2:9) to the time of Christ, when its wood was incorporated into the Cross. The staff was sometimes colored green or depicted sprouting green leaves to signify its connection to the Tree of Life, and the Cross can be depicted similarly.[24]

The blood. The connection to the Arma Christi is most apparent if we interpret the blood as a reference to the blood of the Passover sacrifice and its role in saving the Israelites from death.[25] Late antique references to the Crucifixion present the blood of the Passover sacrifice as an analogue for Jesus’ blood, and Photius’ 9th-century sermon highlights the redemptive power of the blood that flows from Jesus’ body. Some later medieval and early modern illustrations of the Arma Christi include images of the bleeding of Jesus or a large gaping red wound alongside the other implements.[26] The midrash may be playing on the association of Jesus’ blood with the blood of the Passover sacrifice, reclaiming the Passover blood, instead of the blood of Jesus, as an agent of Israel’s salvation.

The Exodus as a Counter-Crucifixion

Each item mentioned in the Haggadah was culled from earlier tradition, but they have been brought together in a way that precisely counters the enumeration of redemptive implements in the early Arma-Christi tradition. The Haggadah thus represents a polemical interpretation of the Exodus as a counter-Crucifixion, wresting from Christians some of the symbolism they used to represent redemption as they understood it.

In later European culture, the Arma Christi were used to stigmatize the Jews—hands shown in a slapping gesture or pulling Christ’s hair are not attached to bodies, but it was understood that they belonged to Jews, and some depictions also include a grotesque face of a Jew spitting at Jesus.[27]

It is possible that the Haggadah was meant as a sarcastic riposte to the role of the Arma Christi tradition as a mode of anti-Jewish caricature. It is also possible, however, that the author was not seeking merely to counter Christian hostility but to tap into the success of the Arma Christi as a way of conceiving redemption, drawing on it as a model for how to conceive God’s intervention during the Exodus. The Haggadah’s midrash not only counters the claim that God had the help of another being in the act of redemption; it comes up with its own enumeration of divine weapons as manifestations of God’s saving power.

Judaism’s Relationship with Christianity

The midrash would thus represent another example of the Haggadah’s two-sided relationship to Christianity—combining anti-Christian polemic with the emulation of Christianity—showing how the midrashic preamble to the Ten Plagues was both influenced by and reacting to a Christian conception of redemption as spiritual warfare.

The author of this midrash in the Haggadah wanted to insist that God’s redemption of Israel was unique, but in commemorating that redemption as a catalogue of divine powers, he reveals himself to be entangled in a spiritual arms race with Christians that involved both competition and imitation.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

April 17, 2024

|

Last Updated

April 18, 2024

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Footnotes

Prof. Steven Weitzman serves as Abraham M. Ellis Professor of Hebrew and Semitic Languages and Literatures and the Ella Darivoff Director of the Herbert D. Katz Center of Advanced Judaic Studies at the University of Pennsylvania. He received his Ph.D. from Harvard University after completing his B.A. at UC Berkeley, and spent several years teaching Religious Studies at Indiana University and Stanford, where he also served as director of their Jewish Studies programs. Weitzman specializes in the Hebrew Bible and early Jewish culture and in his scholarship, he seeks insight by putting the study of ancient texts into conversation with recent research in fields like literary theory, anthropology, and genetics. His publications include The Jews: A History (co-authored with John Efrom and Matthias Lehman), a biography of King Solomon titled, Solomon: The Lure of Wisdom (Yale’s “Jewish Lives” series) and his The Origin of the Jews: the Quest for Roots in a Rootless Age (Princeton University Press, 2017).

Essays on Related Topics: