Edit article

Edit articleSeries

Leviticus as a Literary Tabernacle

Inside view of the Tabernacle, Jan Luyken, 1705. rijksmuseum.nl

Leviticus 25 lays out the laws of shemiṭṭah (letting the land lie fallow every seven years) and the Jubilee (freeing indentured servants every fifty years).[1] The opening verse is unusual for Leviticus:

וַיְדַבֵּר יְ-הוָה אֶל מֹשֶׁה בְּהַר סִינַי לֵאמֹר.

And YHWH spoke to Moses on Mount Sinai, saying.

The most common opening to pericopae in Leviticus is “And YHWH spoke to Moses saying” (וַיְדַבֵּר יְ-הוָה אֶל מֹשֶׁה לֵאמֹר), which appears 27 times;[2] only at Lev 25:1 does the text add, “on Mount Sinai.” Thus, the rabbis ask (Sifra, Behar 1:1):

מה עניין שמיטה לעיניין הר סיני[3]

What is the connection between sabbatical and Mount Sinai?

This rabbinic dictum, which later came to mean why are two seemingly unrelated units juxtaposed, originates as a response to the odd introductory formula in Lev 25:1, which includes the geographical indicator בְּהַר סִינַי “on Mount Sinai.”

Traditional Approaches

The rabbis use this juxtaposition to teach that all the commandments (including, but not limited to, the laws of the sabbatical year) and their particulars (דיקדוקיה) were commanded at Sinai (Sifra Behar 1:1).[4] In his commentary on this verse, Rashi (1040-1105) quotes the Sifraand supports it.

Rashbam and Ibn Ezra

Rashi’s grandson, Rashbam (1085-1158), however, offers a much more prosaic interpretation:

קודם שהוקם אוהל מועד

Before the Tabernacle was built.

In other words, the phrase is meant to tell the reader that even though this passage comes after the building of the Tabernacle, the revelation of the law actually occurred earlier.[5]Rashbam’s contemporary, Abraham ibn Ezra (1089-1167), took the same approach:

אין מוקדם ומאוחר בתורה, וזו הפרשה קודם ויקרא וכל הפרשיות שהם אחריו, כי הדבור בהר סיני.

“The Torah is not necessarily in chronological order”[6] – and this passage comes before the opening passage and all subsequent passages of Leviticus, which come after it, for this revelation happened at Mount Sinai.

Ibn Ezra goes on to explain that the reason this passage is being presented at the end of Leviticus, instead of earlier where it belonged chronologically, is to connect the laws of letting the land lie fallow (shemiṭṭah) with the punishment section, since not keeping this law is one of the reasons Israel will be punished (Lev 26:34-35).[7]

Mary Douglas: A Literary-Structural Approach

The British scholar Dame Mary Douglas (1921-2007) was the most important late-20th-century social scientist to examine sections of the Bible from a serious anthropological vantage point. Most well known, perhaps, is her pathfinding essay on the laws of kashrut, “The Abominations of Leviticus,” included in her 1966 book, Purity and Danger, published near the beginning of her career.[8] Towards the end of her illustrious career, Douglas authored Leviticus as Literature, with the ingenious proposal that the book of Leviticus evinces a literary structure that reflects the layout and configuration of the Tabernacle.[9]

The British scholar Dame Mary Douglas (1921-2007) was the most important late-20th-century social scientist to examine sections of the Bible from a serious anthropological vantage point. Most well known, perhaps, is her pathfinding essay on the laws of kashrut, “The Abominations of Leviticus,” included in her 1966 book, Purity and Danger, published near the beginning of her career.[8] Towards the end of her illustrious career, Douglas authored Leviticus as Literature, with the ingenious proposal that the book of Leviticus evinces a literary structure that reflects the layout and configuration of the Tabernacle.[9]

The springboard for Douglas’ reading was Nahum Sarna’s insight,[10] based on Ramban’s (1194-1270) discussion of the “secret of the Tabernacle” [11] (סוד המשכן), that the Tabernacle is meant to function as an earthly Mount Sinai, and is even designed with the same tripartite division of space laid out in the pericopae on the Mount Sinai revelation (Exodus 19 and 24):

| Tabernacle | Mount Sinai |

| Outer Court – All Israelites | Lower slopes – All Israelites |

| Holy Place – Priests | Halfway up – Aaron and his sons, the elders |

| Holy of Holies – High Priest | Summit – Moses |

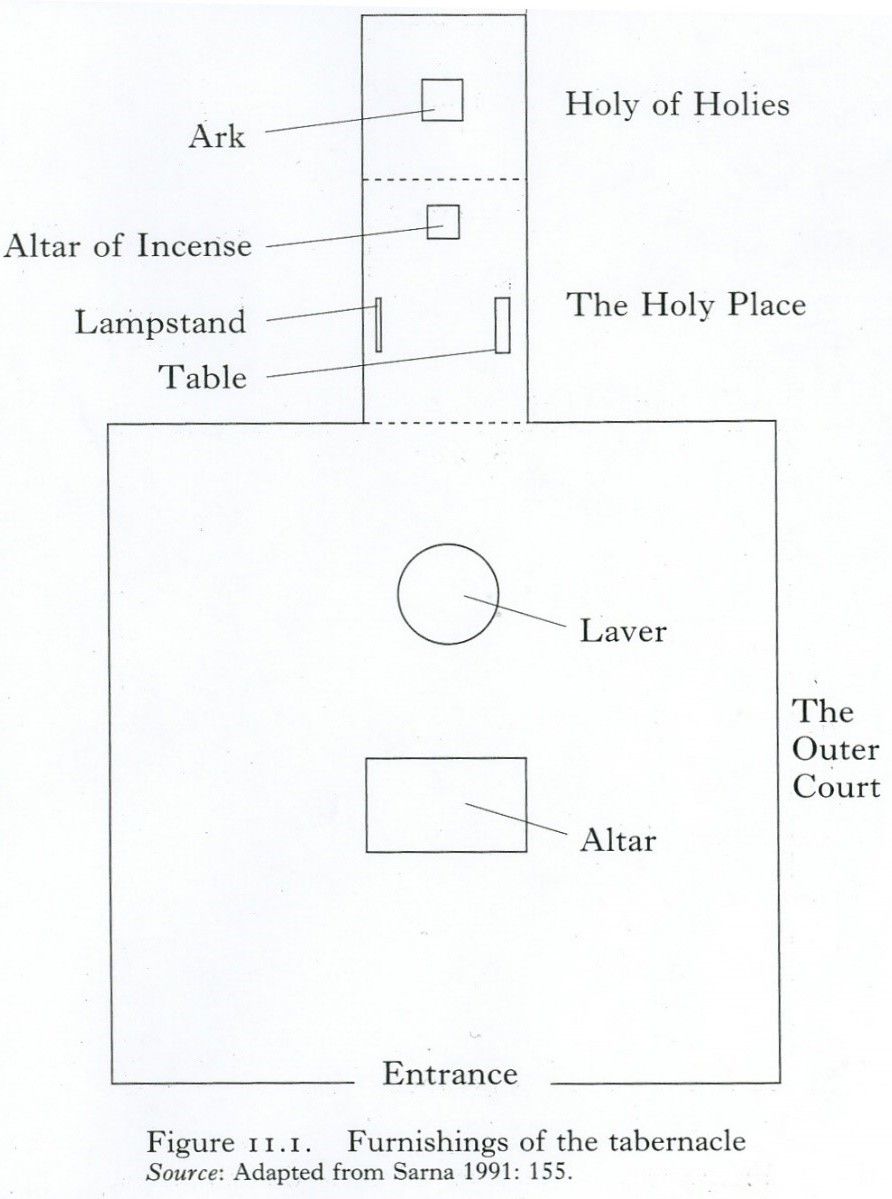

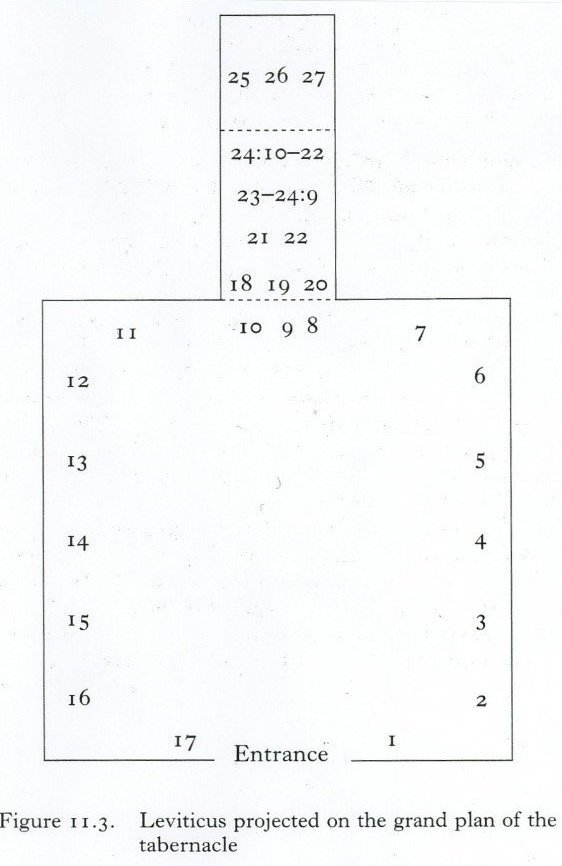

Douglas extended this parallel to the layout of the book of Leviticus.[12] In her analysis (pp. 218-231), the entire book of Leviticus is laid out on the pattern of the Tabernacle, that is to say, in a tripartite division:

(a) Outer Court (chs. 1-17);

(b) Holy Place (chs. 18-24);

(c) Holy of Holies (chs. 25-27).[13]

|

|

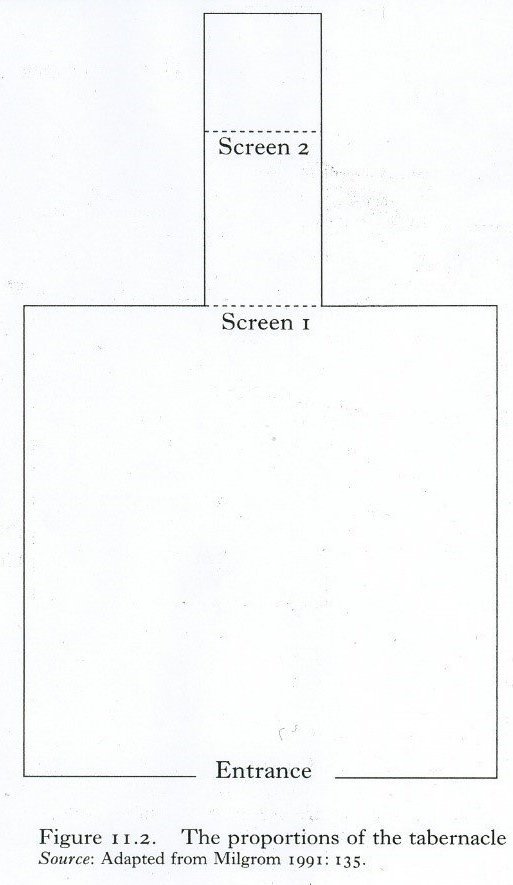

Each chunk of literature corresponds in relative size to the different parts of the Tabernacle, with (a) the largest, (b) the middle-sized, and (c) the smallest.

Structure Reflected in Content

It is not simply the relative sizes of the three parts of Leviticus that match the sections of the Tabernacle, but their contents as well.

Section (a) deals with the sacrifices (chapters 1-7), which were performed in the Outer Court; the laws of purity (chapters 12-15), which governed who could enter the Tabernacle; the laws concerning the slaughtering of animals and the prohibition against eating blood (chapter 17), relevant to the primary activity at the altar; and other related issues.

Section (b) includes laws specific to the priests (chapters 21-22), who alone could enter the Holy Place, and details concerning the lampstand and table (24:1-9), which were located there.

Section (c) focuses on the blessings and curses that will arise if Israel either observes or disobeys the covenant (chapter 26), which is embodied by the ark housed in the innermost sanctum.

In light of these observations, Douglas proposed that the individual chapters of Leviticus be placed on the Tabernacle floorplan, providing the reader with a virtual tour of the locus of Israelite worship as one proceeds through the book.

Too Clever by Half? Or Inherent in the Book?

Is this proposal reasonable? Did Douglas read the structure of the Tabernacle layout into the book of Leviticus, or has the structure been present therein for millennia awaiting its discovery by a 20th-century British scholar? In other words, is Douglas’s approach a case of eisegeis (reading something into the text) or exegesis (extracting nuggets from the text)?

Narratives as Screens

The inclusion of two narratives in the book, in 8-10 and in 24:10-23, supports her thesis. Chapters 8-10 relate the investiture of Aaron and his sons (chs. 8-9) and the strange fire that consumed Nadav and Avihu (ch. 10), while Lev 24:10-23 is the rather extraordinary tale about the blasphemer.[14]

According to Douglas, these two narratives are intended to represent the two screens or curtains that divide the Tabernacle into its three constituent parts. The larger of these two is situated before the screen that separates the Outer Court and the Holy Place, called the masak (Exod 26:36-37, 36:37-38); while the smaller of these units is positioned before the screen that separates the Holy Place from the Holy of Holies, called the paroket (Exod 26:31-35, 36:35-36).

The inclusion and placement of the latter story has long puzzled readers of Leviticus.[15] To my mind, Douglas was the first to provide an explanation for the inclusion and placement of Lev 24:10-23. But her theory of Leviticus’ structure accounts for much more than that.

First Screen: Between the Outer Court and the Holy Place

The narrative of Leviticus 8-10, what Douglas refers to as the first screen, includes four references to the area separating the Outer Court and the Holy Place:

i. Aaron and his sons remained at פֶּתַח אֹהֶל מֹועֵד “the entrance to the Tent of Meeting,” that is, in the area between the first screen and the altar, for seven days (8:31-36).

ii. Moses and Aaron enter the אֹהֶל מֹועֵד “Tent of Meeting,” and then exit to bless the people (9:23):

וַיָּבֹא מֹשֶׁה וְאַהֲרֹן אֶל אֹהֶל מוֹעֵד וַיֵּצְאוּ

And Moses and Aaron came into the Tent of Meeting, and they exited.

This is a very strange verse. As Milgrom notes: “For what purpose did Moses and Aaron enter the Tent? None is cited, and it can only be conjectured.” [16] I suggest that, in keeping with Douglas’ model, it was to highlight the screen, which they traverse in both directions in rapid succession.

iii. Fire came forth מִלִּפְנֵי יְ-הוָה “from before YHWH,” and consumed the offering on the altar of the ordination – for the first time (9:24); this fire must have emerged from the screen of the Holy Place.[17]

iv. The second fire came forth מִלִּפְנֵי יְ-הוָה “from before YHWH,”(10:2) this time the destructive one that consumed Nadav and Avihu, and which once more clearly must have emerged from the Holy Place,[18] that is, again passing through the first screen.

Such a concentration of passages focusing on this particular locus within the greater Tabernacle structure accords with Douglas’s view that the reader of this narrative is in essence walking the perimeter of the Outer Court and halts for a moment in front of the first screen, or masak, which separates the Outer Court from the Holy Place.

Second Screen: Between theHoly Place and the Holy of Holies

The second case (Lev 24:10-23) contains no references to the screen that separates the Holy Place from the Holy of Holies. But the passage that immediately precedes this episode refers to that screen explicitly:

ויקרא כד:ג מִחוּץ לְפָרֹכֶת הָעֵדֻת בְּאֹהֶל מוֹעֵד יַעֲרֹךְ אֹתוֹ אַהֲרֹן מֵעֶרֶב עַד בֹּקֶר לִפְנֵי יְ-הוָה תָּמִיד חֻקַּת עוֹלָם לְדֹרֹתֵיכֶם.

Lev 24:3 Outside the curtain of the Pact, in the Tent of Meeting, Aaron shall set it up (to burn) from evening to morning before YHWH regularly; it is a law for eternity throughout your generations.

The word paroket is specifically used, in fact, in a unique expression, פָרֹכֶת הָעֵדֻת “the curtain [= screen] of the Pact.” The scene, as Douglas emphasized (pp. 227-228), places us within the Holy Place itself, as God commands Moses concerning the lampstand (vv. 2-4) and the table and its loaves (vv. 5-9).

Leviticus’ Summit: Sinai and the Holy of Holies

We now can return to the discussion in the opening section of this essay. Why does the first verse of chapter 25 include the expression בְּהַר סִינַי “on Mount Sinai”? Moreover, this section of Leviticus closes with this expression twice, once at the end of the curses (26:46) and again at the end of the entire book (27:34).

ויקרא כו:מו אֵלֶּה הַחֻקִּים וְהַמִּשְׁפָּטִים וְהַתּוֹרֹת אֲשֶׁר נָתַן יְ-הוָה בֵּינוֹ וּבֵין בְּנֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל בְּהַר סִינַי בְּיַד מֹשֶׁה.

Lev 26:46 These are the laws and the rules and the instructions that YHWH gave, between Himself and the children of Israel, on Mount Sinai, by the hand of Moses.

ויקרא כז:לד אֵלֶּה הַמִּצְוֹת אֲשֶׁר צִוָּה יְ-הוָה אֶת מֹשֶׁה אֶל בְּנֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל בְּהַרסִינָי.

Lev 27:34 These are the commandments that YHWH commanded Moses for the children of Israel on Mount Sinai.

This enveloping of the final section of the book (chs. 25-26/27) as being “from Mount Sinai” is unique in the book of Leviticus.[19]

Following Mary Douglas’ model, I suggest that this enveloping structure is the coup-de-grâce of the author of Leviticus. At this very point in our text the reader enters the Holy of Holies, corresponding to the summit of Mount Sinai, and thus the text brings Moses to that point, or returns him to that point, as it were, by stating explicitly that YHWH spoke to him בְּהַר סִינַי “on Mount Sinai.”

Moreover, this passage functions as the subtlest of references to the second screen. When we understand that “Mount Sinai,” i.e., the summit of the mountain where Moses converses directly with God, represents the Holy of Holies (and vice versa) in Leviticus, for Moses to have reached “Mount Sinai” (i.e., the Holy of Holies), he must have passed through the second screen.[20] The author of our text has managed to surround the short narrative with two reminders of where we are at this point in our journey through the Tabernacle, the one as explicit as can be (the word paroket), the other as allusive as can be (the phrase בְּהַר סִינַי “on Mount Sinai”).[21]

Personal Note

I was privileged to know Mary Douglas (1921-2007) during the last decade of her life. On one memorable occasion I was a guest in her lovely home in Highgate, London (July 2002); and then one year later I hosted her for a lecture series at Cornell University (October 2003). In addition, I was most honored to deliver an oral version of this essay at the Mary Douglas Seminar Series organized by University College London in May 2005, in her presence. I saw Mary Douglas for the last time in December 2005 when she delivered the Carolyn Drucker Memorial Lecture at Princeton University. I dedicate this essay to her lasting memory.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

May 8, 2018

|

Last Updated

September 28, 2024

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Footnotes

Prof. Gary Rendsburg serves as the Blanche and Irving Laurie Professor of Jewish History in the Department of Jewish Studies at Rutgers University. His Ph.D. and M.A. are from N.Y.U. Rendsburg is the author of seven books and about 190 articles; his most recent book is How the Bible Is Written.

Essays on Related Topics: