Edit article

Edit articleSeries

Was Haman Hanged, Impaled or Crucified?

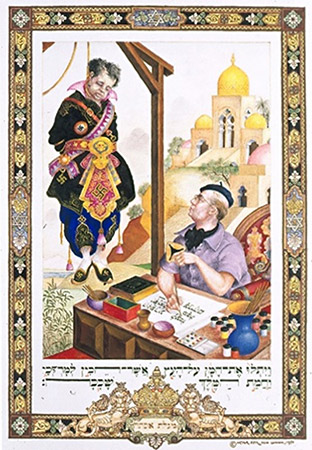

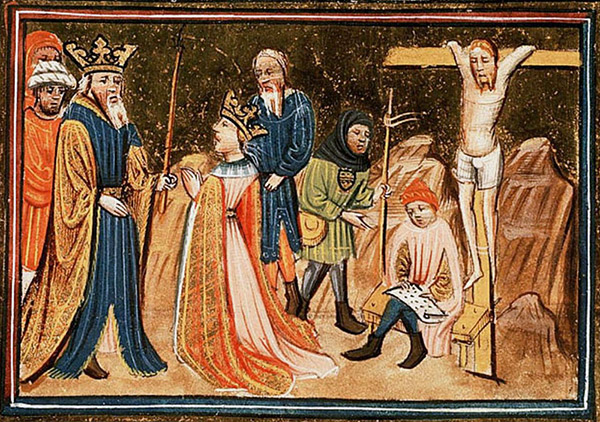

Haman being put to death, in Bible Historiale, 1357, BL Royal 19 D II, f. 237v. British Library

Hanging Haman

For most of us who learned the book of Esther growing up, Haman was killed by being hung on gallows. This seems to be what the Megillah describes in chapter 7. After Queen Esther accuses Haman of trying to have her and all her people killed, Harbona, one of the palace officials tells the king:

אסתר ז:ט ...גַּם הִנֵּה הָעֵץ אֲשֶׁר עָשָׂה הָמָן לְמָרְדֳּכַי אֲשֶׁר דִּבֶּר טוֹב עַל הַמֶּלֶךְ עֹמֵד בְּבֵית הָמָן גָּבֹהַּ חֲמִשִּׁים אַמָּה וַיֹּאמֶר הַמֶּלֶךְ תְּלֻהוּ עָלָיו. ז:י וַיִּתְלוּ אֶת הָמָן עַל הָעֵץ אֲשֶׁר הֵכִין לְמָרְדֳּכָי ….

Esth 7:9 … Look, the very gallows that Haman has prepared for Mordecai, whose word saved the king, stands at Haman’s house, fifty cubits (approx. 75 ft.) high.[1] And the king said, “Hang him on that.” 7:10 So they hanged Haman on the gallows that he had prepared for Mordechai. (NRSV)

The Hebrew word ת.ל.ה/י, means “to hang,” which is understood by many translations, such as the NRSV and the KJV as hanging by the neck on gallows. In fact, the ArtScroll Youth Megillah, the version of Esther that I cherished throughout my childhood, even includes a picture depicting Haman and his servants preparing the long wooden gallows pole upon which to hang Mordecai (Esth 5:14). The illustrated megillah of the famous artist Arthur Szyk (1894–1951) devoted an entire page to verse 7:10 and the gallows.

|

|

Centuries earlier, an illustrated megillah from Ferrara, Italy, published in 1617, depicts Haman dangling from the gallows.

And yet, is Haman hanging on gallows what the author of the Megillah had in mind?

Hanging the Dead Sons of Haman?

On the 13th of Adar, the Jews prevailed over their enemies:

אסתר ט:ה וַיַּכּוּ הַיְּהוּדִים בְּכָל אֹיְבֵיהֶם מַכַּת חֶרֶב וְהֶרֶג וְאַבְדָן וַיַּעֲשׂוּ בְשֹׂנְאֵיהֶם כִּרְצוֹנָם. ט:ו וּבְשׁוּשַׁן הַבִּירָה הָרְגוּ הַיְּהוּדִים וְאַבֵּד חֲמֵשׁ מֵאוֹת אִישׁ. ט:ז וְאֵת... ט:י עֲשֶׂרֶת בְּנֵי הָמָן בֶּן הַמְּדָתָא צֹרֵר הַיְּהוּדִים הָרָגוּ...

Esth 9:5 So the Jews struck down all their enemies with the sword, slaughtering, and destroying them, and did as they pleased to those who hated them. 9:6 In the citadel of Susa the Jews killed and destroyed five hundred people. 9:7 including… 9:10 the ten sons of Haman son of Hammedatha, the enemy of the Jews…

The results of the battle are reported to the king, after which Ahasuerus asks Esther if there is anything else she requires:

אסתר ט:יג וַתֹּאמֶר אֶסְתֵּר אִם עַל הַמֶּלֶךְ טוֹב יִנָּתֵן גַּם מָחָר לַיְּהוּדִים אֲשֶׁר בְּשׁוּשָׁן לַעֲשׂוֹת כְּדָת הַיּוֹם וְאֵת עֲשֶׂרֶת בְּנֵי הָמָן יִתְלוּ עַל הָעֵץ. ט:יד וַיֹּאמֶר הַמֶּלֶךְ לְהֵעָשׂוֹת כֵּן וַתִּנָּתֵן דָּת בְּשׁוּשָׁן וְאֵת עֲשֶׂרֶת בְּנֵי הָמָן תָּלוּ.

Esth 9:13 Esther said, “If it pleases the king, let the Jews who are in Susa be allowed tomorrow also to do according to this day's edict, and let the ten sons of Haman be hanged on the gallows.” 9:14 So the king commanded this to be done; a decree was issued in Susa, and the ten sons of Haman were hanged. (NRSV)

Why do they hang the corpses of Haman’s sons?

Post-Mortem Hanging of Bodies

The hanging of a dead body post execution is described in the book of Deuteronomy:

דברים כא:כב וְכִי יִהְיֶה בְאִישׁ חֵטְא מִשְׁפַּט מָוֶת וְהוּמָת וְתָלִיתָ אֹתוֹ עַל עֵץ.

Deut 21:22 If a man is guilty of a capital offense and is put to death, and you hang him on wood.

Here the hanging is to shame a person after they have been executed. Joshua does this to the five kings he had just defeated:

יהושע י:כו וַיַּכֵּם יְהוֹשֻׁעַ אַחֲרֵי כֵן וַיְמִיתֵם וַיִּתְלֵם עַל חֲמִשָּׁה עֵצִים וַיִּהְיוּ תְּלוּיִם עַל הָעֵצִים עַד הָעָרֶב. י:כז וַיְהִי לְעֵת בּוֹא הַשֶּׁמֶשׁ צִוָּה יְהוֹשֻׁעַ וַיֹּרִידוּם מֵעַל הָעֵצִים וַיַּשְׁלִכֻם אֶל הַמְּעָרָה...

Josh 10:26 After that, Joshua had them put to death and [their bodies] hanged on five wood, and they remained hung on the wood until evening. 10:27 At sunset Joshua ordered them taken down from the wood and thrown into the cave…

The hanging of Haman’s sons fits with this practice. In these passages, however, the Bible is not picturing gallows or hanging people by their necks as a method of execution. Instead, the Bible is envisioning a different practice common in the ancient Near East.

Impaling Bodies

The Hebrew root ת.ל.ה/י can mean hang. But in the context of corpses, it most likely means “impale,” and thus עץ here means not “tree” or “gallows” but “stake.”

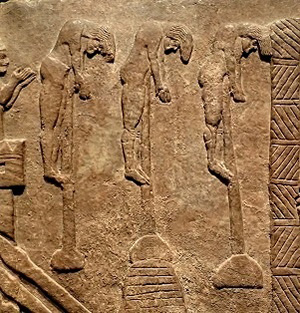

Assyrian reliefs depict the Assyrians impaling their enemies upon stakes. Consider the image to the right from the palace of the Assyrian monarch Tiglath-Pileser III (reg. 745-727) in Kalhu, which depicts the aftermath of an attack on an enemy town.

The defeated dead hang upon stakes. Perhaps they died there as well. Several Judeans themselves suffered this punishment at the hands of King Sennacherib of Assyria, as we can see from the reliefs in his palace at Nineveh depicting the conquest of Lachish. Such was a form of posthumous punishment and humiliation in the ancient world.[3]

Persian society, the very setting of Esther, continued to disgrace bodies of foes by impaling them. In the Behistun inscription, a multilingual text commissioned by the ruler Darius the Great (550-486 BCE), Darius claims to have hung up his enemies’ bodies.[4] The Greek historian, Herodotus (ca. 484–425), makes the same claim about Darius in his description of the capture of Babylon (Histories 3.159):

So was Babylon captured for the second time. When Darius became its master, he pulled down the walls and wrenched the gates from their hinges… Darius also impaled (ἀνεσκολόπισε) three thousand of the chief men but turned the town over to the rest of the Babylonians.[5]

Impaling Haman

Applying this to the book of Esther, it seems likely that לתלות על העץ should be translated “to impale on a stake.” For Haman, impalement also served as the method of execution while for his sons, it was a post-mortem rite of humiliating the corpses. The translation of “hang from the gallows” is an anachronistic retrojection of the common European form of execution on a book set in ancient Persia.[6]

The Crucifixion of Haman

Just as early modern translators imagined Haman being killed by a method with which they were familiar, ancient Greek translators also imagined something familiar to them, namely crucifixion, the standard Roman punishment which most resembles impaling.

The LXX (Septuagint) translates Ahasuerus’ command about Haman as “crucify him upon it,” from the Greek word “stauro-” (σταυρόω).[7] Similarly, the Latin Vulgate refers to the pole upon which Haman and then his sons are hung as patibulum, meaning “cross.”[8]

In his retelling of the story, Josephus Flavius (37–100) also writes about crucifixion (Ant. 11.266–267, LCL trans.):

And then came the eunuch Sabuchadas (=Harbonah), and accused Haman, saying that he had found a cross (σταυρὸν) at his house prepared for Mordechai…. And the cross, he said, was sixty cubits in height. When the king heard this, he decided to inflict on Haman no other punishment that that which had been devised against Mordechai, and ordered him at once to be hanged (κρεμασθέντα) on the very same cross till he was dead.

While Josephus never uses the verb “to crucify” here, he consistently refers to the object as a cross.[9]

Haman and Jesus

The interpretation of Haman’s death as crucifixion had serious consequences in late antiquity, since the crucifixion of Haman suggested to Jewish minds a connection with Jesus.[10] In fact, Jews used this obvious parallel for polemical effect.

An Aramaic poem in honor of Purim,[11] composed towards the end of Late Antiquity (400-600 C.E.), imagines Haman conversing with all the great tyrants of Jewish history, such as Pharaoh and Nebuchadnezzar.[12]

After each villain complains about his failure, Haman retorts that his story contains more tragedy. Towards the end of the poem, Haman talks with Jesus, who chastises Haman and claims that his own lot was the worst of all. The poetry focuses on death by crucifixion, the feature of life that both Jesus and Haman share:[13]

סבר את בגרמך / דאת צלב בגרמך / ואנא שותף עימך

You think only of yourself,/ that you alone were crucified,[14] / but I participated alongside you

סמרי על קיס / ודמותי במרקוליס / מצייר על קיס

Nailed unto the cross (i.e. wood, AB) / I looked like a statue of Mercury (Roman god of commerce and luck, AB) / depicted on wood.

סמרי על קיס / ובשרי לטופח נקיס / ובר נגיד בקיס

They nailed me up on a cross /and a handbreadth-wide gash was flogged from my flesh / and a ‘Son’ was stretched out upon a cross.

סכיף באסקוטוס / מן אתא זיניטוס / וקרון יתי כריסטוס

Scourged with a whip / of woman born: / ‘Tis I who am called Christ.

סמר במסמרין / בגפיי מסמרין / טב מני אכל שעירין

Studded with nails / driven into my limbs / an “eater of barley” is better off than I.

סופיה די נקיבת / עבדין בהתה / בכל אתר ומדינתה

In the end, the pierced one / is worshipped in shame / in every town and city.

In this Jewish re-telling of the Passion narrative, Jesus identifies himself with Haman. Both men were put on a cross. But that is where the parallel ends. Jesus acknowledges Haman’s pain, but asserts that he suffered torment and ignominy that far eclipsed that of Haman.

Response to the Jewish Lampoon

For some ancient Jews, singing this poem likely functioned as a pressure-release valve. The daily hard and soft forms of Christian persecution for which they could not seek political, social or military redress were rectified in the performed space of fictive poetic drama. Instead of fomenting rebellion, Jews re-crucified Haman (= Jesus) every Purim.[15]

And some Christians noticed. On May 29th, 402 C.E., the Roman emperor sent out the following declaration:

The governors of the provinces shall prohibit the Jews from setting fire to (H)aman in memory of his past punishment during a certain ceremony of their festival, and from burning with sacrilegious intent a form cast in the shape of a holy cross in contempt of the Christian faith, lest they mingle the sign of our faith with their jests. They shall also restrain their rituals from ridiculing Christian law because if they do not abstain from matters that are forbidden they will promptly lose what had been thus far permitted to them (Theodosian’s Code 16.8.18).[16]

Some Jews evidently burned a crucified Haman in effigy as a Purim practice. Christians—seeing a figure on a cross aflame—felt anxious. Who is on fire: Haman or Jesus? Setting the former alight might be acceptable. Doing so with the latter strikes at the heart of Christianity. The visual parallel between Jesus and Haman irked Roman authorities enough to demand that Jews cease this form of Purim revelry.[17] We see from here that, at least in some cases, reimagining the death of Haman had real-world consequences.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

February 23, 2021

|

Last Updated

April 15, 2024

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Footnotes

Dr. AJ Berkovitz received his Ph.D. in Religion from Princeton University for his dissertation, The Life of Psalms in Late Antiquity. He the co-editor of Rethinking ‘Authority’ in Late Antiquity: Authorship, Law, and Transmission in Jewish and Christian Tradition (Routledge, 2018), and the author of several articles. He currently serves as Assistant Professor of Liturgy, Worship and Ritual at HUC-JIR in New York.

Essays on Related Topics: