Edit article

Edit articleSeries

Bring the Man to the Carcass or the Carcass to the Man?

Dead cow After a Flood in Oosterbeek, Johannes Hubertus Leonardus de Haas, 1842-1908. Rijkmuseum

The ancient Greek translation of the Torah, known as the Septuagint (LXX), begun in the 3rd century B.C.E., broadly reflects the Torah we have today. Nevertheless, it does not fully agree with the Masoretic Text (MT). Some of these discrepancies are probably due to the translator having had a different Hebrew text (Vorlage—German for “that which lay in front of,” namely the Hebrew text from which the translator worked); in some cases Hebrew texts that agree with the LXX against the MT have been found among the Dead Sea Scrolls. Other discrepancies may be due to conscious interpretive adjustments. In this article, I want to showcase a third type of change, one that stems from the lack of vowels in the Hebrew text.

The Torah is written in unpointed Hebrew, i.e. without vowels.[1] Although modern Jewish chumashim do include vowels, this vowel system developed slowly in the second part of first millennium C.E. This explains why none of the Dead Sea Scrolls, dating through the early second century of the common era, contain vowel signs. Different competing systems were created to represent how Hebrew was read, and the one we use was developed in Tiberius; a competing system, which marks vowels above the letters, was developed in Babylonia. When the Greek Text of the LXX was written, however, there were no vowel signs or cantillation marks; this would have extended to boundaries of interpretation significantly.

An excellent example of this comes from this week’s parasha (Mishpatim), which contains the following rule regarding an unpaid guardian who loses the object he was given to look after (22:9-12):

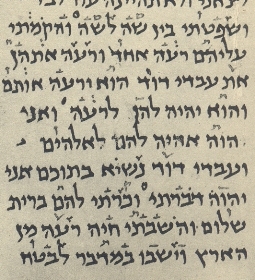

שמות כב:ט כִּי יִתֵּן אִישׁ אֶל רֵעֵהוּ חֲמוֹר אוֹ שׁוֹר אוֹ שֶׂה וְכָל בְּהֵמָה לִשְׁמֹר וּמֵת אוֹ נִשְׁבַּר אוֹ נִשְׁבָּה אֵין רֹאֶה. כב:י שְׁבֻעַת יְהוָה תִּהְיֶה בֵּין שְׁנֵיהֶם אִם לֹא שָׁלַח יָדוֹ בִּמְלֶאכֶת רֵעֵהוּ וְלָקַח בְּעָלָיו וְלֹא יְשַׁלֵּם. כב:יא וְאִם גָּנֹב יִגָּנֵב מֵעִמּוֹ יְשַׁלֵּם לִבְעָלָיו. כב:יב אִם טָרֹף יִטָּרֵף יְבִאֵהוּ עֵד הַטְּרֵפָה לֹא יְשַׁלֵּם.

Exod 22:9 When a man gives to another a donkey, an ox, a sheep or any other animal to guard, and it dies or is injured or is carried off, with no witness about, 22:10 an oath before YHWH shall decide between the two of them that the one has not laid hands on the property of the other; the owner must acquiesce, and no restitution shall be made. 22:11 But if [the animal] was stolen from him, he shall make restitution to its owner. 22:12 If it was torn by beasts, he shall bring evidence/testimony (עֵד); the torn carcass he need not replace.

The meaning of the word עֵד in verse twelve is unclear. Following the common Rabbinic understanding, Rashi suggests,

רש"י שמות כב:יב יביא עדים שנטרפה באונס ופטור.

Rashi Exod 22:12 He should bring witnesses that it was torn [by beasts] through no fault of his own, and he will be exempt [from making restitution.]

According to Rashi, the term עֵד should be translated literally as “witness” and refers to actual human witnesses to what occurred. Presumably, if there were no witnesses to the event, the custodian would have to repay the loss.

Rashi’s grandson, Rashbam, interprets עֵד not as human witnesses but as physical evidence:

רשב"ם שמות כב:יב קצת מאיברי הטרפה לעדות

Rashbam Exod 22:12 Some of the pieces of the cadaver he should bring as evidence.

It seems that Rashbam believes that according to the peshat there is no need to bring actual witnesses. Bringing pieces of the cadaver to demonstrate that it was killed by wild beasts is sufficient proof. This is the view of the Targum Yerushalmi and R. Avraham ibn Ezra as well.[2]

A similar approach is taken by the New JPS translation, which by and large follows the Masoretic text, reads, “If it was torn by beasts, he shall bring it as evidence.” The main difference between NJPS and Rashbam/ibn Ezra/Targum Yerushalmi is practical rather than fundamental. The NJPS assumes that the custodian must bring the entire carcass. This makes some sense since, presumably, the owner would wish to recognize the animal and see how it died. On the other hand, Rashbam et al. could reasonably claim that an entire carcass is very heavy and difficult to carry back to the owner.

These practical considerations beg a more simple solution: why not just bring the owner to the carcass. In fact, this is exactly what the LXX says the custodian should do,

If the animal was torn by beasts, he shall bring him (=the owner) to the carcass and he shall be exempt from restitution.[3]

Logically, this position makes a lot of sense. It is difficult to carry a carcass and it always best not to touch the crime scene. But how can the LXX offer this reading? Was the translator working with a different text? The answer, I believe, is that the LXX translator had the same text, but read the Hebrew differently.

The letters ע.ד. in the MT are pointed with a tzeiri, forming the word “witness.” In addition, the word has the etnachta cantillation mark (עֵ֑ד), which indicates a major pause. The LXX translator, however, read the word as if it had (what would later be called) a patach (עַד), meaning “until,” and did not have the pause. Reading it this way, the phrase means “until” or “up to” the carcass.

Not only is this a very reasonable read of the verse, but this interpretation actually appears in Rabbinic literature as well. For instance, the Jerusalem Talmud (Baba Kama 1:1) offers this reading in the name of Bar Padaya.[4] Similarly, the 11th century work, Midrash Lekach Tov records this (presumably Tannaitic) debate:

מדרש לקח טוב שמות כב:יב א”ר יוסי בר יאשיה: "אם טרף יטרף יביא עדים שנטרפה באונס ויהא פטור מלשלם."ר’ נתן אומר: "יביאהו עד הטריפה, יוליך את הבעלים אצל הטריפה ויהיה פטור מלשלם."

Midrash Lekach Tov Exod 22:12 Said Rabbi Yossi bar Yoshiah: “If it is torn by beasts, he should bring witnesses that it was torn through no fault of his own and he will be exempt from making restitution.” Rabbi Nathan says: “Bring him to the carcass, i.e. bring the owners to the carcass, and then he will be exempt from making restitution.”

This debate is exactly the difference between Rashi’s view and that of the LXX.[5] Targum Pseudo-Jonathan (a 6th century Aramaic translation of the Torah mistakenly attributed to the tanna Jonathan ben Uziel) actually records both options in its translation:

אין אתברא יתבר מן חיות ברא מייתי ליה סהדין או ימטיניה עד גופא דתביר לא ישלם.

If it was torn by wild animals, he should bring witnesses to this fact or bring him (=the owner) to the carcass that was torn and he need not pay.

These Rabbinic texts point to the strong possibility that even during the Rabbinic and early post-Rabbinic period (Targum Pseudo-Jonathan is from around the 6th cent. C.E.), the masorah of the pointing and cantillation was not set, and the rabbis themselves were unsure how to punctuate and pronounce the words.

So how should the word be read, “eid” or “ad”? When it comes to the Torah reading on Shabbat, tradition mandates reading “eid.” (In other words, do not correct the ba’al koreh!) And yet, looking at the debate about how to pronounce this little word offers us a glimpse into the world of Torah before pointing and cantillation, a world that contains a number of possible readings of the biblical texts.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

January 24, 2014

|

Last Updated

February 18, 2026

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Dr. Rabbi Zev Farber is the Senior Editor of TheTorah.com at the Academic Torah Institute. He holds a Ph.D. from Emory University in Jewish Religious Cultures and Hebrew Bible, an M.A. from Hebrew University in Jewish History (biblical period), as well as ordination (yoreh yoreh) and advanced ordination (yadin yadin) from Yeshivat Chovevei Torah (YCT) Rabbinical School. He is the author of Images of Joshua in the Bible and their Reception (De Gruyter 2016) and co-author of The Bible's First Kings: Uncovering the Story of Saul, David, and Solomon (Cambridge 2025), and editor (with Jacob L. Wright) of Archaeology and History of Eighth Century Judah (SBL 2018). For more, go to zfarber.com.

Essays on Related Topics: