Edit article

Edit articleSeries

The Elephantine Passover Papyrus: Darius II Delays the Festival of Matzot

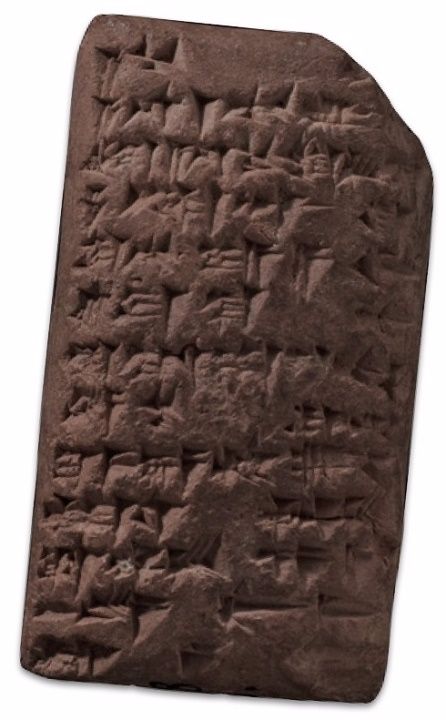

Elephantine, Credit: British Museum

The Isle of Elephantine (Yev)

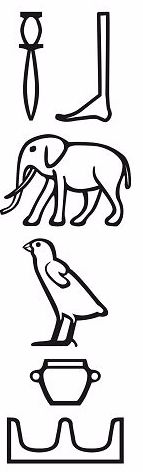

A tiny island, less than one kilometer square, is located on the southern border of Egypt, in the middle of the Nile. Its ancient Egyptian name was ʾAbu—pronounced Yev in Aramaic and Hebrew—meaning elephant or ivory.[1] In English, it is known as Elephantine. This island’s minute size belies its significance for understanding the Bible and the history of Yahwism.[2]

Judeans Move to Elephantine

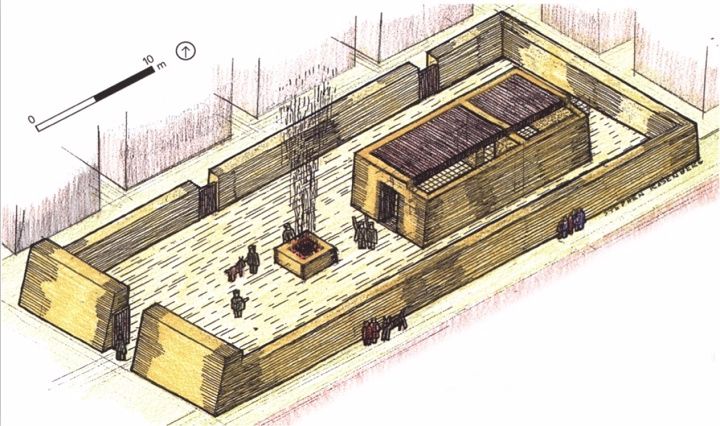

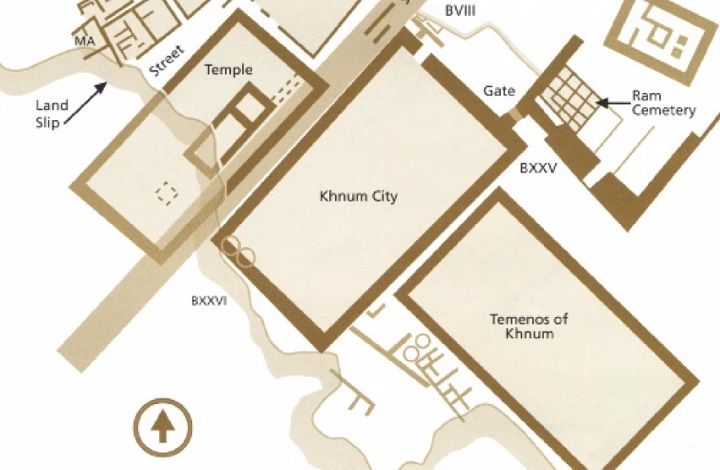

No later than the sixth century BCE, a community of Judean expats settled on the island and in the adjacent mainland settlement of Syene (Aswan). For at least part of the community’s history, many of its members belonged to a Persian military garrison. In this distant outpost, they observed Yahwistic customs, even establishing a temple of YHWH (spelled YHW), complete with a sacrificial cult. Remarkably, their temple was located mere meters away from a large temple complex devoted to the Egyptian god, Khnum, leading to considerable tension and occasional hostility.[3]

The Cache of Documents

The community in Elephantine remained in contact with their brethren in Judea, and—incredibly—a trove of documents including these correspondences (and much more) survived in Elephantine and Aswan. Most of these artifacts were unearthed more than a century ago, but there have been some recent discoveries, as well.[4] Some of these documents were misfiled or forgotten—languishing for decades in museum store rooms—and are only now beginning to see the light of day.[5]

The documents produced by this community are quite diverse, consisting of contracts, letters, and literature, including the earliest attested copy of the popular deuterocanonical Story of Aḥiqar.[6] The texts are primarily in Aramaic, including some that are written in demotic Egyptian script (as well as vice versa).

Jewish-ish Practices

The names of the ex-Judean residents ranged from the biblical—Nathan, Haggai, Isaiah—to the decidedly Egyptian—Eswere, meaning “the great Isis.” Members of the community took oaths in the names of Satis (an Egyptian goddess associated with Elephantine), YHWH, Anatyahu (hybrid of YHWH and the Semitic goddess, Anat, who was popular in Egypt), etc. Several cases of intermarriage are attested, as well.

Since the Elephantine corpus has not undergone the sort of scribal revision that is typical of biblical material, it is a particularly valuable historical resource. These writings provide unique evidence for the real-life experiences of Yahwists in the biblical period.[7]

The So-Called Passover Papyrus

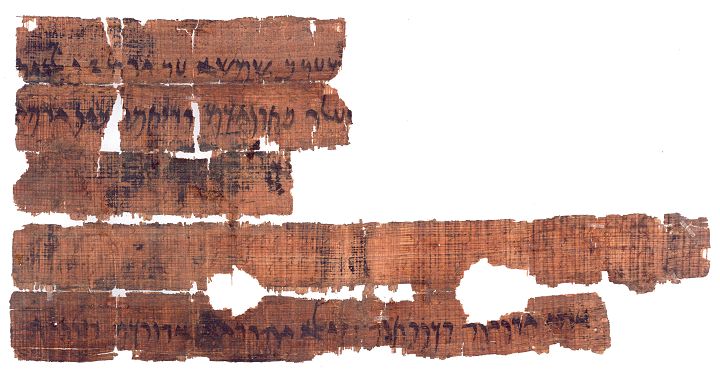

With this in mind, let’s turn our attention to the most famous Elephantine document of all, the so-called Passover Papyrus. It contains a letter sent in 418 BCE by Hananiah, who was evidently affiliated with the Achaemenid administration, and who some speculate is the biblical Hanani, brother of Nehemiah (Neh 1:2, 7:2).[8] Hananiah’s letter was addressed to the Judean garrison in Elephantine and its leader, Jedaniah, and is made up of two sections, both fragmentary.

Papyrus recto – credit Bruce and Kenneth Zuckerman |

Papyrus verso – credit Bruce and Kenneth Zuckerman |

Following the formal greeting, the text begins with a message sent from King Darius II to Arsames, satrap (governor) of Egypt. The content of this message was lost in its entirety. The second section relates to the Feast of Matzot. It mentions the festival’s dates, as well as practices associated with it. A widely-accepted reconstruction of the letter follows:

[אל אחי י]דניה וכנותה ח[ילא י]הודיא אחוכם חננ[יה] שלם אחי אלהיא [ישאלו בכל עדן]

[To my brothers, Je]daniah and his colleagues the [J]ew[ish] ga[rrison,][9]your brother Hanan[iah]. May God (the gods?) [seek after] the welfare of my brothers [at all times.]

וכעת שנתא זא שנת 5 דריוהוש מלכא מן מלכא שליח על ארש[ם] […]

And now, this year, year 5 of King Darius, it has been sent from the king to Arsa[mes] […]

יא כעת אנתם כן מנו א[רבעת עשר יומן לניסן וב14 בין שמשיא פסחא עבד]ו ומן יום 15 עד יום 21 ל[ניסן חגא זי פטיריא עבדו שבעת יומן פטירן אכלו כעת] דכין הוו ואזדהרו עבידה

Now, do you count [fourteen days in Nisan and on the 14th at twilight observe the Passover] and from the 15th day until the 21st day of [Nisan the festival of Unleavened Bread observe. Seven days eat unleavened bread. Now,] be pure and take heed.

א[ל תעבדו ביום 15 וביום 21 וכל מנדעם זי שכר א]ל תשתו וכל מנדעם זי חמיר א[ל תאכלו ואל יתחזי בבתיכם מן יום 14 לניסן ב]מערב שמשא עד יום 21 לניס[ן במערב שמשא וכל חמיר זי איתי לכם בבתיכם ה]נעלו בתוניכם וחתמו בין יומיא[ אלה] […].א

[Do] n[ot do] work [on the 15th day and on the 21st day. And] do [n]ot drink [anything of leaven. And do] n[ot eat] anything of leaven [nor let it be seen in your houses from the 14th day of Nisan at] sunset until the 21st day of Nisa[n at sunset. And b]ring into your chambers [any leaven which you have in your houses] and seal (it) up during [these] day[s]. […]

[אל] אחי ידניה וכנותה חילא יהודיא אחוכם חנניה ב[ר …][10]

[To] my brothers Jedaniah and his colleagues the Jewish garrison, your brother Hananiah s[on of …].

What is the connection between the message from King Darius II to Arsames, on the one hand, and the Feast of Matzot, on the other, and what is it that the Elephantine community is being told “to count”?

Standard Reconstruction: Count Fourteen Days Until the Passover

Most scholars reconstruct the gaps in the second part of the letter in light of Pentateuchal passages pertaining to the Passover and Feast of Unleavened Bread.[11] The most substantial of these reconstructions—one which has achieved broad consensus since it was first proposed in 1911—is of the lacuna immediately preceding the dates of the Matzot festival:

כעת אנתם כן מנו א[רבעת עשר יומן לניסן וב14 בין שמשיא פסחא עבד]ו ומן יום 15 עד יום 21 ל[ניסן חגא זי פטיריא עבדו]. [12]

Now, do you count [fourteen days in Nisan and on the 14th at twilight observe the Passover] and from the 15th day until the 21st day of [Nisan the festival of Unleavened Bread observe].

Passover Papyrus?

Despite the letter being known as the “Passover Papyrus,” the Passover is nowhere to be found in its extant sections; it appears only in scholars’ conjectured reconstructions. This is not to suggest that the Passover (paschal sacrifice) was not observed in Elephantine—it is indeed mentioned on two ostraca (inscribed potsherds) found on the island. However, neither Passover ostracon refers to the Festival of Matzot, just as this papyrus makes no mention of the Passover. This is notable, particularly given that the Festival of Matzot and the Passover were originally separate entities.[13]

Alternative Reconstruction: Declaring a Leap Year

As I argue in a forthcoming article,[14] the aforementioned reconstruction is likely incorrect, and we should instead read “count [an additional] Adar” ([מנו אדר [יתר). In other words, the letter says nothing about Passover, and Darius II was not concerned about Jews keeping chametz (leaven) out of their homes on the Festival of Matzot. The king’s message to Arsames, satrap of Egypt, can be paraphrased as: “You and your province, along with the rest of the empire, must add a second Adar this year.” This new reading clarifies the logical connection between the two parts of the letter.

Having received word of this development, Hananiah sent an urgent message to the community in Elephantine, the upshot of which was: “Do not celebrate the Festival of Matzot in the usual time; it will be a month later this year!” Following the breaking news, Hananiah also mentioned some relevant practices, but the letter’s primary function was a leap-year alert.

The Leap Year in the Achaemenid Period

The Achaemenids began reckoning leap years according to fixed tables only in the fourth century; during Darius II’s reign, the king still exercised his discretion, adding either a second Adar or a second Elul as he saw fit. Serendipitously, ancient records confirm that the year in question, the fifth year of Darius II’s reign, was indeed a leap year, and that the intercalated month was Adar![15]

All this strengthens the case that at this time-period, no Yahwistic or Judean body had independent calendrical authority;[16] the biblical festivals were celebrated according to the Persian civil calendar.[17]

In conclusion, the remarkable “Passover Papyrus” adds even more color to our already vibrant picture of the community of Yahwists in Elephantine. At a time when some of the books of the Bible were still being composed, these Judean immigrants celebrated an extraordinary Festival of Matzot. Its date was not set by their brethren in Jerusalem, nor did they determine it for themselves; it was dictated by the Zoroastrian emperor. Together with their Egyptian spouses and relatives, they observed the holiday that traditionally marks the Exodus from Egypt as they stood mere steps from the temple of Khnum, the Nile god, on the border of Egypt and Nubia.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

April 5, 2017

|

Last Updated

January 29, 2026

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Dr. Idan Dershowitz completed his undergraduate and graduate training at the Hebrew University, following several years of study at Yeshivat Har Etzion. In 2017, he was elected to the Harvard Society of Fellows. Dershowitz was previously Chair of Hebrew Bible and Its Exegesis at the University of Potsdam and is currently Senior Lecturer of Premodern Jewish Studies at Monash University. He is the author of two books: The Dismembered Bible: Cutting and Pasting Scripture in Antiquity and The Valediction of Moses: A Proto-Biblical Book.

Essays on Related Topics: