Edit article

Edit articleSeries

Decoding the Table of Nations: Reading it as a Map

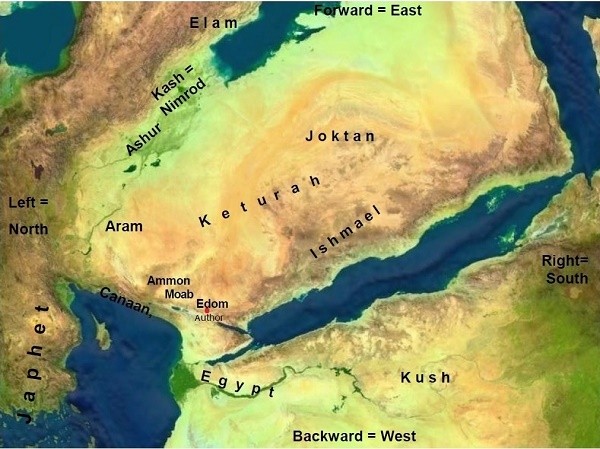

Table of Nations insert: H. Karnoefel/Wikimedia

The Table of Nations in Genesis 10 lists the nations known to the author,[1] depicting them all as the descendants of Noah’s three sons, the only families to survive the flood. A number of problems with this genealogical tree have convinced scholars that this table does not represent the real relationship between these peoples.

Placing Peoples in the Wrong Groups

Using linguistic and historical criteria, a number of anomalies stand out.[2]

- Canaan is in Asia, and its language group, Phoenician-Hebrew, is Semitic. Yet the text describes Canaan as a descendent of Ham (v. 6), whose descendants are in North Africa and whose language groups are (for the most part) Egyptian and Cushitic.

- The Hittites are from Asia Minor (Turkey) and spoke an Indo-European language, and thus should belong to the children of Japhet, yet Het, their progenitor, is listed as one of Canaan’s sons (v. 15).[3]

- The Philistines, many of whom lived in western Turkey or on the Levantine coast, are probably Aegean in origin and are believed to have spoken a form of Greek, yet they are mentioned among the offshoots of Egypt (vv. 13–14).[4]

If linguistic and historical criteria are not what determine genealogical relationship in this text, then what criteria are the Torah using?

Geographical References in the Chapter

In a few verses within the list, the Torah moves away from merely cataloguing the names of descendants and states where on the map they lived or acted.

- The Torah describes the building projects of Nimrod and the cities of Ashur without mentioning their descendants (vv. 10–12).

- Canaan has his border specifically drawn as a triangle marked by his furthermost cities (v. 19).

- We are told the region where the children of Joktan are situated (v. 30). [5]

In my view, to understand the logic behind the grouping of the various nations in the list we need to think geographically, and the key we need to decipher the code of the Table of the Nations is a map.

Canaan in the Center?

As stated above, the borders of Canaan are described as a triangle.

יט וַֽיְהִ֞י גְּב֤וּל הַֽכְּנַעֲנִי֙ מִצִּידֹ֔ן בֹּאֲכָ֥ה גְרָ֖רָה עַד־עַזָּ֑ה בֹּאֲכָ֞ה סְדֹ֧מָה וַעֲמֹרָ֛ה וְאַדְמָ֥ה וּצְבֹיִ֖ם עַד־לָֽשַׁע:

19 The Canaanite territory extended from Sidon as far as Gerar, near Gaza, and as far as Sodom, Gomorrah, Admah, and Zeboiim, near Lasha.

The image of a triangular territory is particularly apropos here. In ancient society, the center of a map represented either the draftsman’s location or the center of Earth, or both.[6] Thus, we can assume that Canaan was meant to be in the center of the map. Since there are three sides to a triangle, the author of the genealogy implies that each of Noah’s sons can be found on one side of this triangle—roughly, Shem in the northeast/east (Syria and Iraq), Ham in the south (Arabia and Africa), and Japhet north/west (Turkey and the Aegean)—with the land of Canaan situated in the middle.

The Canaan Triangle – A Redactional Insertion

The above is what the inclusion and placement of the Canaan map implies, but when we try to understand the chapter according to this scheme, the placement of the peoples makes little sense. If anything, the map of Canaan here is misleading.

Here are some problems we encounter:

- Six of Canaan’s descendants are located north of Sidon, outside of the triangle, which ends at Sidon.[7]

- The children of Joktan, who are on the Shem list (26–29) and should, therefore, dwell amongst the other Semites northeast of the land of Canaan, in fact dwelt in Arabia (southeast).

These items are in serious tension with the map we envision with Canaan in the middle. For this reason, I would like to suggest that the triangle that marks the land of Canaan (v. 19) is not original to this chapter but was added by a Cisjordanian scribe to an older map which did not envision Canaan as the center.[8]

Where would we locate the center of the map if we looked only at the remaining verses?

A Map with Transjordan in the Center

In two articles on TheTorah.com, “Locating Beer-lahai-roi” and “Mourning for Jacob at Goren Ha-Atad,” I presented the argument that much of the J document in the Torah derives from and reworks older Transjordanian Israelite traditions that originated in Kadesh (=Petra). In keeping with this hypothesis, I propose that the draftsman responsible for the original Table of the Nations, before the addition of v. 19, also belonged to this group, and that to understand the genealogy as it was intended, we must use a map with Petra—not Canaan—in the center.

Guidelines for Understanding the Map

A few basic rules, common to ancient Near Eastern conceptions of geography and maps, can help us read the text properly.

- East is the primary direction, and thus it comes first on the list. (In fact, one of the words for east in ancient Hebrew, קדם, also means “forward.”)

- Right comes before left.

- Geographic distance is manifest in genealogic distance and vice versa. The closer to Petra, the closer the relationship that group will have to Israel on the genealogical tree.

Now let us see the world through the eyes of the author of the map.[9] To make the picture fuller, I will begin with Israel’s closest relatives from later on in the Torah (descendants of Lot, Abraham, and Isaac). The author of the genealogy in chapter 10 could not give a full picture of the world as he knew it and had to leave the nations closest to his own out artificially, since these nations (Moabites, Edomites, etc.) are only introduced as part of the history of the patriarchs.[10]

Our geographer-genealogist is located in Petra/Kadesh, probably standing on one of the mountains, facing eastward. In front of him is the territory of Edom/Esau, which became the twin brother of Jacob/Israel (Gen 25:30, 36:43).

To his right (= to the south) is the territory of Ishmael, Jacob’s uncle, his father’s brother (Gen 25:12-18). The further he advances southward, the deeper he enters the Ishmaelite genealogy. To the east of Esau and the Ishmaelite tribes are the descendants of Keturah, who are cousins: the descendants of Grandfather Abraham from his concubine (Gen 25:1-4).

To his left (= to the north) are Moab and Ammon, the descendants of Lot, who are the grandchildren of Haran, Abraham’s brother (Gen 19:38-39). Moab is the closer of the two geographically to our creator of the map. And needless to say, Moab is the son of the firstborn daughter. This is how the author would have viewed his closest neighbors, whom he discusses later in the Torah.

All of this territory is envisioned in ch. 10 as the territory of Eber and of his ancestor Arpachshad. (Ishmael, Esau, and Lot “inherited” Eber’s territory.) In front (=east) and to the left (= to the north and northeast) of Eber are the brothers of his grandfather Arpachshad: Elam, Ashur, Lud, and Aram (v. 22).[11]

Behind the author, in the west, beyond the Syro-African rift valley (including the Jordan River, the Dead Sea, and the Red Sea), are the seed of Ham: first Canaan, in Asia, then Egypt, Kush, etc., in Africa. Also behind him, far to the north in Asia Minor or far to the west in the Aegean, are the offspring of Japhet.

Genealogical Proximity Equals Geographic Proximity

Reading the genealogy this way, as an expression of the geographic proximity or distance from the Israelite author in Kadesh, many of the problems in this chapter are solved.

- Canaanites are from Ham and related to Egyptians because they are behind the author, to the northwest.

- Canaan’s descendants can be found outside the triangle because the triangle is an artificial supplement to the J genealogy, aimed at conveying the editor’s perspective, not at making the genealogy more coherent.

- Joktan is east of the rift valley, and therefore still part of Shem.

- In the time of the author, Hittite elements and the Philistines dwelt in the Cisjordan or just north of it. Thus, they are Hamites and related to Canaan.[12]

In short, the genealogy in chapter 10 explains the proximity or distance of nations from the Transjordanian Israelites by claiming that it is based on their familiar relationship with Israel. The original center of this geographic distribution was the Transjordan, specifically Kadesh/Petra.

The delineation of the territory of Canaan as a triangle, implying that it stands at the central point of the map, was added by the editor. This element served to demonstrate his own geographic point of view, with the Cisjordan in the center. The shift of the map’s center prevented scholars from decoding the genealogy of the Table of Nations, making it impossible to understand. Read without this addition, the details of the map fall into place… that is, as long as you know where the author was standing.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

October 16, 2015

|

Last Updated

February 10, 2026

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Dr. David Ben-Gad HaCohen (Dudu Cohen) has a Ph.D. in Hebrew Bible from the Hebrew University. His dissertation is titled, Kadesh in the Pentateuchal Narratives, and deals with issues of biblical criticism and historical geography. Dudu has been a licensed Israeli guide since 1972. He conducts tours in Israel as well as Jordan.

Essays on Related Topics: