Edit article

Edit articleSeries

Abraham, Smasher of Idols, and the Question of the Torah’s Historicity

Abraham destroys his father Terah’s idols, Herlingen Haggadah, Vienna, 1725, f. 4v (detail). e-codices

The Midrashic Abraham

בראשית רבה נח פרשה לח אמר ר' חייא תרח עובד צלמים הוה, חד זמן נפק לאתר הושיב אברהם מוכר תחתיו, הוה אתי בר נש בעי דיזבון, אמר ליה בר כמה שנין את, אמר ליה בר חמשין, אמר ליה ווי לההוא גברא דאת בר חמשין ותסגוד לבר יומא, והוה מתבייש והולך לו,

Gen Rab 38 Rabbi Chiyya said: Terah was an idol worshiper. Once he went on a trip and he placed Abraham in charge of the store in his place. When a man would come to buy [an idol], [Abraham] would ask him: “How old are you?” The man would respond: “Fifty.” [Abraham] would reply: “Whoa to this man, you are fifty years old and yet you bow to one who is only a day old!” The man would then feel embarrassed and slink away.

חד זמן אתת איתתא טעינא חד פינך דסלת אמ' ליה הא לך קרב קדמיהון, קם נסיב בוקלסה ותברהון ויהב ההוא בוקלסה בידוי דרבה דבהון, כיון דאתא אבוה אמר ליה מה עבד להון כדין, אמר ליה מה נכפור לך אתת חדא איתתא טעינא חד פינך דסלת ואמרת לי קרב קומיהון, דין אמר אנא אכיל קדמאי ודין אמר אנא אכיל קדמאי, קם הדין רבה נסיב בוקלסה ותברהון,

One time a woman came carrying a dish of fine flour. She said to [Abraham]: “Here, offer this before them.” [Abraham] picked up a staff and broke [the idols] and placed the staff in the hands of the largest of them. When his father returned, he asked him: “Why did you do this to them?” [Abraham] replied: “Would I hide it from you? A woman came carrying a plate of fine flour and she told me to offer it before them. Each one of them said, ‘I will eat first’ until the largest of them picked up the staff and shattered the others.”

[אמר ליה] מה את מפלה בי, ידעין אינון, אמר ליה ולא ישמעו אזניך מפיך, נסתיה ומסרתיה לנמרוד...

[Terah] responded:“Why are you trying to fool me? I know what they are!” [Abraham] retorted: “Do your ears not hear what your mouth is saying?!” [Terah] took him and brought him before Nimrod…

Let us open with a simple question, an example that may seem minor: did Abraham shatter the idols in his father’s store as was described in the above midrash? Personally, I believe the answer to be yes, Abraham did, in fact, shatter the idols in his father’s store. Yet, not everyone believes this to be the case.[1]

There are those who claim that the author of the midrash wished to complete Abraham’s incomplete biography, and thus to deal with the question of why God specifically chose Abraham out of all people on earth.[2] Taking this approach, the author of the derasha is filling in the gaps in the Torah’s description of Abraham, which describes God’s appearance to him without any introduction or explanation.

Alternatively, there are those who suggest that the author of the derasha wished to call our attention to the foolishness of idolatry and idol worshipers, and he decided to express this with wit and poignancy by writing a story and placing it into the life story of Abraham, the father of monotheism.

Neither of these approaches are less traditional than the one I articulated as my own; each finds expression in the words of some of our traditional commentators, who remove the midrashic account from any real-life context. Instead, they look for the story’s underlying ideas, accentuating the religious and moral lessons embedded in it. These commentators show little interest in incorporating the details of the story into what we would call history.

The question of the historicity of the midrash seems like a low hurdle to jump over on our way to dealing with the important ahistorical religious notions we glean from the story. The many traditional interpreters who seem unconcerned with the midrash’s historicity contribute to the ease of jumping this hurdle. Nevertheless, there exists a hurdle which appears much higher and harder to clear, and that is the following question: If it is possible for us to say that the midrashic Abraham does not reflect historical reality, but rather represents various ethical and moral ideals, can we say this about the biblical Abraham as well? More accurately, can we say this about Abraham in general, the man himself? In other words, was there an Abraham?

Recoiling at Historical Misgivings

The very suggestion of the possibility that the biblical Abraham is not a flesh and blood historical figure shook the pillars of traditional thought centuries ago.[3] Even in our days, this possibility causes ripples when it is proposed in the presence of a diverse array of religious people. This deep and instinctive recoiling experienced by many different believers should not be dismissed with a mere shaking of the head, nor is it sufficient to point to the lack of rational grounds at its core.

This reaction has an enormous impact on religious discourse and requires serious attention. It is incumbent upon us to deliberate honestly about the reasons for this recoiling. If it is possible for us to explain a midrash as ahistorical—and there were many sages who objected even to this over the millennia—why shouldn’t we expand this possibility to include interpretations of biblical passages as well?

Looking carefully at the sources for the objection to the ahistorical interpretation, we find that there are two main objections, the slippery slope problem and the truth problem.[4] Let us look at each in turn.

A. The Slippery Slope or The Domino Effect[5]

The intuitive rejection of the possibility that Abraham is the protagonist of a story and not a historical figure can be explained on the basis of the following consideration: If we were to say that Abraham never existed, then, in theory, we could say the same about Isaac and Jacob. Where would we stop? If our patriarchs never existed, how did they go down to Egypt? Even worse, did the Exodus from Egypt happen? Perhaps worst of all: Did God’s revelation on Mount Sinai happen?

This type of consideration does not a priori invalidate possible reasons to stop the process of ahistorical reading—for example, perhaps there is a way of distinguishing between the patriarchal period and that of the Exodus. Rather it undermines their value since the possibility always exists that someone else, unconvinced by one’s reason for dividing between one story and another, will take the process of ahistorical reading even further. For this reason, since the Torah, as a single narrative complex, is without any historical anchor other than tradition, it is incumbent upon us to protect the tradition from every side and to keep critical scholarship at a distance, even from parts of the narrative whose historicity appears insignificant, lest the critical methodology plant its seeds there. In other words, let us say that Abraham existed so that no one suggest that his descendants never existed, and they never went down to Egypt, and never left Egypt, and never received the Torah at the footsteps of Mount Sinai!

In truth, the question of the historicity of the exodus from Egypt and the receiving of the Torah at Sinai is enormously challenging, but I will save it for another occasion.[6] For now, I wish to focus on the rhetorical and logical structure of the slippery slope argument. The slippery slope argument bases itself upon the claim that one must sometimes stake one’s claim over a minor matter in order to fortify one’s position on a more serious and central matter; sometimes one must put up a fence a great distance from the danger point and establish clear borders so that the uninitiated can avoid pitfalls.[7]

The slope does not get less slippery—perhaps it even gets slipperier—as it enters the world of religious practice. The trajectory of ahistorical interpretation may pose a serious threat to the observance of mitzvot. If Abraham and Sarah never existed on this earth but are merely abstract symbols—“matter” and “form”, for example, as some medieval Jewish philosophers suggested—are the mitzvot, then, also just abstract symbols? Perhaps they are just theoretical principles expressed as concrete rules; rules, whose intellectual and moral bases we should try to understand but not laws we should actually keep in any practical way.[8] Every symbolic reading of a Torah passage, even one that has no direct connection with any mitzvah, grants added weight to the feeling and idea that biblical verses are primarily symbolic. Each symbolic reading risks uprooting the foundation of halachic obligation, which expresses itself in the real world as Jewish observance.[9]

B. The Problem of Truth

Another pillar upon which the opposition to ahistorical reading has been founded is the problem of truth. Like the previous pillar (the slippery slope argument), this argument takes into consideration the entirety of the Torah, but comes at it from a different angle. The claim is as follows: If Abraham is only a literary character, this places the entire corpus of Torah into the genres of fiction, fable, and myth.

Since Abraham never existed, was never a flesh-and-blood person, then all that the book of Genesis says about him are merely tales. In other words, they aren’t true. How can it be that the divine Torah, which is presented as truth and has pretentions to being the “Truth”, busies its readers, students, and adherents with concocted stories?![10] Only a Torah that happened—meaning that the narratives presented in it occurred in the concrete past as described—can be considered true and trustworthy. A Torah that tells tales is nothing more than a work of fiction.[11]

I would like to engage this position in its own language, but with the opposite premise. To my mind, a narrative tale is no less “true” than a historical description; it can be just as valuable, even truer than it, in a certain sense.

Tradition vs. Text in Chazal

In order to establish this proposition and make it easier for people to digest, allow me to veer a little bit from the path we have been trodding thus far in the essay, and turn to a Talmudic concept that is only tangentially related to our discussion, but which may shed some needed light upon it.

The Talmud (b. Sanhedrin 4a-b) describes two possible ways to read the language of the Torah: “the received text is paramount (yesh eim le-mesoret)” and “the accepted recitation is paramount (yesh eim le-mikrah)”. The words of the Torah—at least some of them—can be read in more than one way. Take, for example, the word שבעים in Lev. 12:5, “If she bears a female, she shall be unclean שבעים.” The word could be read as shevu’ayim, i.e. “two weeks,” as it is pointed in all of our chumashim and, more significantly, as we have been accustomed to reading it for generations, even before there was pointing in our Hebrew texts. This reading is based on the premise that accepted recitation is paramount, according to which the main factor guiding our interpretation of a word in the Torah is the way it has been understood in Jewish tradition over the years.

Nevertheless, this very word could be read without making recourse to the traditional vocalization of it (which finds its concrete expression in the pointing), giving power to the written form of the word which itself has been passed down in tradition over the generations. Such a reading would be based on the premise that the received text is paramount. For if we were to simply look at the way the word is written in the Torah, i.e. in its defective (chaser) spelling, and we were simply to suggest the most intuitive reading of the term, we would undoubtedly say that the word before us is shiv’im, “seventy,” i.e., the impurity should last seventy days.

The first approach to reading of the Torah is not surprising. In order to pave the way for this reading various techniques have been adopted such as pointing the word (שְׁבֻעַיִם), or adding matres lectionis (שבועיים). The second approach, however, is rather surprising. Hasn’t the meaning of the word, with its halachic implications, been determined by the way it has been read over the generations? From whence sprang the suggestion to interpret the Torah against the way it has been read? Can one really neutralize the “true” meaning of a verse and read shiv’im (seventy) instead of shevu’ayim (two weeks)?

In order to answer this question let us investigate the basis for this phenomenon: what is the point of writing? The main purpose of contracts and newspapers, for example, is to translate the real world—where a deal was struck or something worth describing occurred—into writing. Writing, not just in these examples, is a reality substitute of great value. A business deal that took place before witnesses, but without documentation, can end up being a source of dispute and fraud if the witnesses disappear and never return. An event with significant import to the wider population that is never reported will end up being known by only a handful of people who witnessed it.[12]

Writing, especially in the above examples, allows people who were not witnesses to the events to meet the reality of the event in a mediated encounter. As such, writing is secondary to the event itself. The business deal or the event is the main matter of significance, describing the event in writing is simply a means of conveying knowledge of that deal or event to others. Thus, whenever a question arises about something written, our goal would be to try and get as close as we can to reproducing the event as it occurred, to analyze the event itself, if possible, in order to learn “what really happened.” We would not shy away from reading alternative descriptions of the event, even contradictory ones, and compare these versions to the one we have in our hands.

The way the Sages understand Scripture is quite different. In their understanding, the written text is not there to convey an event; it is the event itself. It is the Torah of God, turning its face to Torah students in every generation. The fervent attempt to capture some meaning in each and every word of the Torah, without making recourse to any external factors as a control, is a clear expression of this perspective. It is this difference, which lies at the heart of the distinction between the two interpretive methods described above.

The interpretive strategy of “the accepted rendition is paramount” emphasizes the importance of our mediated encounter with the text, the reading that I was taught by my teacher, and he his teacher, going all the way back to ‘the law given to Moses at Sinai.’ In short, the tradition is of utmost value.

The interpretive strategy of “the received text is paramount” takes an entirely different approach, which attempts to encounter the word of God without any mediation.[13] The sacred written Torah is the teaching of God and it is forbidden to learn it indifferently. Its meaning is not dependent on external evidence; its narrative descriptions should not be characterized as reconstructions or preservation of past events. Such narrative strategies, as I mentioned above, would be subject to factual investigation as well as comparative evidence, taking into account alternative versions. Instead, the text of the Torah should be understood on its own terms; the Torah itself is the matter being studied. Therefore, we should be careful not to miss even a single hint or implication that may be imbedded in the direct speech of God to us.

Ahistorical Torah: God’s Narrative

Our analysis of the “truth problem” leads us to this summary statement: Whenever we as readers encounter a description of an event in the Torah, the main concern for us as students of Torah is not the reality of the event as it happened but the event as described in the biblical narrative. This point can be expressed in two different ways. The first and simplest is, “What the Torah says about the event is what is important.” The second is shorter but sharper, “What the Torah says is what is important.”

The first statement, the simpler one, would probably be acceptable to anyone. The Torah describes various events from its own unique perspective. These events occurred at some point in the past, and the Holy Author (God) describes them from the unique perspective of the divine. It is this perspective in particular, and the interpretation of the event expressed in it, that is of interest, religiously speaking, for within this retelling of the event lies its religious value. The believer, who adapts the divine message to his or her own life, chooses to look upon the events of the past described in the Torah from the divine perspective.

Nevertheless, juxtaposed to this more moderate phrasing, we placed a more radical one. According to this second phrasing, the events described in the Torah are part of God’s narrative; whether this narrative has a basis in historical fact doesn’t matter. A divinely originated narrative has no need for “real” historical events in order to grow sinews and flesh and become something substantial. The believer who adopts this narrative wishes to engage it directly. When he or she reads the accounts of our father Abraham in the Torah and wishes to understand their significance, what he or she wants is not to find out more about the (possible) historical character behind the story but to encounter the protagonist of the narrative, i.e. the literary character.

Studying the “real life” of the giant among men, our founding father, Abraham the man of faith and kindness, would, in theory, give us an opportunity to uncover the God in which he places his trust. Nevertheless, such an opportunity would be limited. As our rabbis taught us, “all is in the hands of heaven except for fear of heaven (b. Berachot 33b);” even the historical Abraham would have to fit into this rubric. Therefore, by necessity we would need to distill from his historical persona what parts of his life were his own choice, (i.e. not in the hands of heaven,) in order to say something about the God he discovered and followed.

Contrast this with the literary Abraham, the Abraham who is the fruit of the spirit of God and the divine pen. This Abraham is entirely in the hands of heaven (in a different and positive sense). In an ahistorical reading, we exchange Abraham the man, his biographic details—only some of which have any connection to God—with God’s Abraham. In essence, we exchange a conversation about God for an encounter with God.

Presenting the Torah as God’s narrative does not take away from its religious significance. The opposite is the case. Understanding the Torah this way can strengthen the deep vitality buried in its every story, every verse, every word – even every letter. These could now be understood as virtually physical expressions of the divine message. Even religious feeling, if it is possible to speak of this as a thing, is poised to gain from the intimate connection that is formed between humanity and God, when one understands the Torah as God telling a story just as a parent tells a story to his or her child.

What Is History?

One of the questions that occupies philosophers of history as a discipline has been, to what extent can a historian really reconstruct the past and to what extent is he or she actually reshaping it? One approach (the older and more naïve one) claims that the job of a historian is to make a copy of the past and place it, as-is, before present day students of history. A different approach (cutting edge and more realistic) assumes that reconstruction of the past, with a point-by-point accurate portrayal, is impossible. Therefore, it is the job of the historian to tell his or her story about history. In this story, he or she creates a new reality that never before existed, or, to be more precise, he or she describes a reality that bears a relationship with events that did occur in the past, but is not an exact replica of those events.

This second approach, in my opinion, works well with what seems to be occurring in the biblical narratives. When the Torah describes various events that appear to be rooted in a concrete time and place, its account is more a retelling than a reconstruction. The Torah crafts its story line purposefully in such a way as to support the aims of the Narrator, including the Narrator’s values and moral lessons. Moreover, the traditional approach to Torah, which accompanies the study of the written text, greatly emphasizes the function of studying the past for contemporary times. This is the meaning of the phrase, “In every generation a person must look upon himself as if he left Egypt.”[14]

This perspective is reflected in the world of halacha as well. Among the many events described in the book of Genesis, there are a handful that carry with them a mitzvahrequirement—the circumcision of Abraham (Gen. 17) and the injuring of Jacob’s sciatic nerve (Gen. 32:25-33), for instance. Although these events have halachic weight in Jewish tradition, this is not because they happened in the past (before the revelation at Sinai) but because they were included in the Torah’s narrative at Sinai.[15]

If the stories about the ancestors of the nation had not been included in the Torah at Sinai, it seems likely that they would be without any religious implications. The giving of the Torah at Sinai turns a story or mitzvah included in it into the barometer for proper religious behavior.[16] Only from the time of its inclusion in the Sinai covenant could a given law become the Archimedean point for the spiritual makeup of a person. Rambam expressed this idea in his unique idiom,

Anyone who accepts the seven mitzvot (of the Noahides) and is careful not to violate them should be considered one of the righteous gentiles and has a share in the World to Come. This, however, is when this person accepts the [mitzvot] and fulfills them because the Holy One commanded this in the Torah and informed us through our teacher Moses, that the descendants of Noah had been so commanded (Mishneh Torah, “Laws of Kings,” 8:11).

Following the analysis offered here, the halachic tradition makes the religious value of any historical event that occurred before the revelation at Sinai contingent upon the power given to it by its inclusion in the narrative that came down to the world at Sinai. Considering this, insofar as observance is concerned, is it important to defend the belief that all of the stories narrated in the book of Genesis actually happened? Cautiously, I would like to suggest that doing so is not important.

If the religious value of events comes from their being included in the word of God, let us allow God to speak to us in God’s own language, and to tell us the divine story with its entire force. Would we really be unable to give ear and listen to God’s story with great focus, attention, and feeling unless we could simultaneously locate it in a specific time and place? Will God’s story be diminished if we do not connect it with the actions of specific people, as great as they may have been?

Let’s imagine that God’s message is cloaked with descriptions of events that modern day historians believe cannot be accepted as fact—so what? Does the story become less powerful, less complete, less true?[17] Is it surprising that God’s narrative is the story of humanity writ large?

It is about humanity’s religion and its faith, its moral struggles, its successes and failures, its hopes and aspirations for greatness, its dream of breaking into the world of the infinite and clinging to God. Is there a truer story than this? Is it less true than a simple chronology of events describing the beginning of the world and of humankind?[18] Is it less significant than a partial biography of a given individual, who lived 3500 years ago in some insignificant part of the world?

Pushing Back

As I was leading a discussion in the beit midrash on this subject, one of the participants pushed back against this approach. “If this is a story,” he said, “it is a very human story. Shouldn’t we expect from God a more coherent story, one that is free of the subtle and even blatant contradictions that can be found within it?” Another participant argued that he still couldn’t see, despite my explanation, why the Torah chose to speak to us in historical language.

In response to the first question, I admitted that I am not trying at all to prove that the biblical author was God. I simply believe it. If I were pushed to offer some sort of response to this question anyway, I would say that just as any great author can breathe life into his or her characters and describe them from many angles, so too can the Divine Author, the greatest of authors. I am not surprised, therefore, at the literary prowess—very much like human literary prowess—demonstrated in Torah by its author.[19] The various literary layers identified by biblical scholars in the text do not contradict its status as divine.[20] Moreover, even if the Torah had been written from one perspective only, in one clear and flowing style, that would not have proven that it came from God. It would always have been possible to claim that one author, Moses for instance, wrote it on his own.

Although I felt able to push the first question into the sidelines, the second question seemed to me more problematic. Why did God choose to limit the divine creative impulse to the (apparently) inadequate framework of narrative? To attempt an answer, I suggest that dry mechanical lists of rules, such as “do not murder and do not steal”, couldn’t accomplish the transmission of lofty values to humankind. In order for such values to find a permanent place in the spiritual life of individuals, they must be narrated. Perhaps they even needed to be narrated in exactly the way the Torah itself narrates them.

The power of a story cannot be found purely in the ideological explication of the divine message contained within, even if the message once understood, requires a person to live up to it in his or her life. Instead, the full power of the divine message comes once the message finds its place within a person’s heart. This is something best accomplished by narrative, not by list of laws or principles.

Establishing the Palace of Torah on Higher Ground

When I ask myself the question, “What is more important: that Abraham lived in Ur 3500 years ago, or that he should live for 3500 years in the hearts of the people of Israel,” I choose the second option. There is also a third option, of course, that the Abraham who lived in Ur continued to live in the hearts of Israel. Nevertheless, this possibility brings to mind the old joke about the elephant and the ant.[21] Did the elephant really need the ant in order to make dust-clouds in the desert? Does the Torah’s Abraham really need the historical Abraham in order to claim an important role in Jewish religious consciousness?[22]

Getting accustomed to this kind of thinking about the Torah is required, in my opinion, if a person wishes to acquire the ability to raise his or her faith in Torah from a peripheral attachment to an essential attachment to its contents. Seeing the Torah as the story of God establishes a person’s faith in Torah from Heaven at its highest and purist level. Such a perspective does not diminish the connection between humanity and God; it strengthens it.[23]

It is, furthermore, impossible to deny another benefit of the ahistorical model of understanding the Torah’s narratives. Establishing the pillars of faith upon the bedrock of the historicity of past events requires an honest person to evaluate, without bias, the question of the historical reality of the Torah’s claims. In a world where there are many doubts about the historicity of core events in the Torah’s narrative,[24] establishing the palace of Torah upon a higher foundation would seem to be a constructive goal.[25]

Freeing the Torah from its historical crutches not only frees the narrator from having to keep the narrative in line with past events, but it also neutralizes the basis for the attack against the validity of a person maintaining his or her faith. An ahistorical Torah is not subject to being “disproven” by archaeology or academic historical reconstructions.

Postscript

Existential or Non-Essential

I cannot deny that the intuition of religious people, whether they be simple believers or great scholars, prefers to see the Torah’s narratives as based in factual history. These events are seen—not without cause—as being singular and special.[26] Therefore, even if a believer’s intellectual powers allow him or her to consider the possibility that an ahistorical Torah could be more sophisticated and spiritual than a historical one, nevertheless, he or she cannot ignore the outer voice—or even the inner voice—that makes it difficult to be satisfied with scholarly justifications.

In many ways, the challenge faced by such a person is similar to the one faced by Rambam when he tried and demonstrate to the world that God has no body.[27] Putting this view forward before those who believed that God had a body probably caused those believers a crisis of faith. The simple reader of Maimonides—and even the not so simple reader—was likely to feel that the loss of God’s body was almost equal to the loss of God. Many in Maimonides’ generation believed that the existence of God was coterminous with God’s physical existence.[28] Although they believed that the great and majestic body of God was not comparable to their small and weak bodies, nevertheless, they could not let go of a God with some sort of a physical body.

How is one to deal with such a tremendous challenge? What is a believer to do, when he or she is convinced that a new religious outlook, as innovative and brazen as it may be, not only doesn’t diminish the value of faith but even colors it in stronger and more vibrant colors?[29] How should this believer relate to the fact that the very type of faith that he or she sees as inferior is exactly the one which sits best with the majority of the faithful? It is precisely the struggle of thinkers like Rambam and Rav Kook that can be most helpful in answering such questions. It is precisely this struggle with which I attempt to grapple in my book.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

February 12, 2014

|

Last Updated

January 30, 2026

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

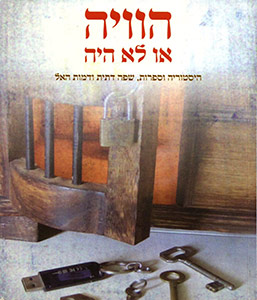

Dr. Rabbi Amit Kula is the rabbi of Kibbutz Alumim as well as of Beit Midrash “Daroma” at Ben Gurion University. He did his Ph.D. in Jewish thought at Ben Gurion University, focusing on the writings of Rav Kook. Kula was formerly the Rosh haYeshiva of Yeshivat HaKibbutz HaDati in Ein Tzurim. He is a member of the rabbinic organizations Tzohar and Beit Hillel, has written a number of online responsa, and is the author of Existential or Non-Essential: History and Literature, Religious Language and the Nature of the Deity.

Essays on Related Topics: