Edit article

Edit articleSeries

The Historical Uniqueness and Centrality of Yom Kippur

On the eve of Yom Kippur (Prayer). Artist Jakub Weinles (1870–1935)

Part 1

The Significance of Yom Kippur

“Yom Kippur,” the day of ritual and moral cleanness and self-denial, has become the climax of the Jewish High Holy Days. This day is the hope for freshness and new beginning for individuals and for the collective. Once a year, on the tenth of the seventh month (Tishre), the high priest atones (כפר) for impurities of the Temple and the altar, and at the same time also for sins of all the people: himself, his close family, his priestly clan, and all Israel (Lev 16:10-11, 16-19, 21-22, 24, 29-33; 23:27; Num 29:7; Exod 30:10). In fact, atonement of the people is the core of the Yom Kippur ritual (Lev 16:6-11, 15, 17, 21-24, 30-32), while the atonement of the Temple and the altar is mentioned only secondarily (Lev 16:16, 18-20, 33).

The biblical text states: “For on that day [shall the priest] make an atonement for you, to cleanse you, that you may be clean from all your sins before the Lord” (Lev 16:30).[1] Despite the evident meaning of the term “all your sins,” the rabbis learn from the phrase “before the Lord” that Yom Kippur atones for sins “between man and God” (בין אדם למקום) only, and this too, only under certain conditions.[2] For the sins “between man and his fellow” (בין אדם לחברו), one must appease his fellow and request forgiveness. In case he or she harmed another, he or she must pay compensation or return the stolen goods.[3]

Yom Kippur and the Akītu Festival

The uniqueness of Yom Kippur and its rituals are obvious when compared to the Babylonian New Year festival (Akītu) in the month of Nisan. The latter lasted not a single day as Yom Kippur, but eleven or twelve days, and its aim was mainly atonement for the temple, and parenthetically also for the king, who went through humiliating rituals.

Furthermore, in the Babylonian rite the high priest was not involved in the atonement of the temple. It was accomplished by lower temple-servers. The Babylonian high priest just read a hymn to the gods at early morning and spoke some words at the end of the service. Thus, the similarity between Yom Kippur and Akītu is very general and the differences significant.[4]

The Centrality of Yom Kippur for all groups of Jews

The significance of Yom Kippur in the Israelite/Jewish religion is evident from its central literary location in the holiest Scripture of Judaism – the Torah: it is placed in the book of Leviticus, which comes after Genesis–Exodus but before Numbers–Deuteronomy. In Leviticus, it is described in chapter 16, which serves “as a culmination to all of chapters 1-15.”[5]

Furthermore, because of the importance of the day, its ritual is to be performed almost entirely by the high priest, that is, by one who stood on the peak of the priesthood hierarchy (Lev 16:1-28, 32-33). To cite Tosefta Horaiot 2:1: “all Yom Kippur’s ritual is unacceptable unless it has been performed by him” (כל עבודת יום הכיפורים אינה כשרה אלא בו). Also, this is the only day of the year that the high priest is allowed to enter the inner sanctum of the Temple – the Holy of Holies (Leviticus 16; Mishnah, Kelim 1:9; Hebrews 9:7).

Given that Yom Kippur is only mentioned in Priestly sources, its antiquity is unknown. Nonetheless, at some point in the Second Temple period the day was considered as such, and has been so ever since. Yom Kippur was considered a High Holiday by the Qumranites; the Sadducees, the Pharisees and their successors, the Rabbinites;[6] it remains central to the Karaites (ca. 750 C.E. and on), the Samaritans, and in contemporary Judaism.

Part 2

The Significance of the Jerusalem Priest’s

Attack on the Qumranite Leader

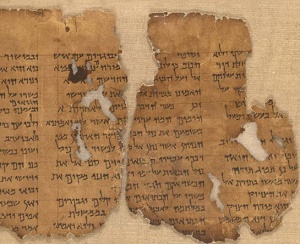

Pesher Habakkuk (1QpHab) of the Dead Sea Scrolls[7] is generally dated to the second half of the first century B.C.E. The Scroll teaches about the history of the late Second Temple period, more than about the biblical book of Habakkuk. Since usually the prophetical verses were considered as allusions to the future historical events in the life of God’s people, the author of 1QpHab 11.2-8 actualizes the biblical verse (Habakkuk 2:15):

“Woe to the one who gives his neighbor to drink, adding in his poison, making him drunk, in order to gaze upon their feasts(מועדיהם).[8]

The author of Pesher Habakkuk interprets this verse to reflect a tale that happened in his own time. He expounds the verse about the Wicked Priest (כוהן הרשע), most probably the high priest,[9] who attacked the Righteous Teacher (מורה הצדק) – who also was a priest – on the Day of Atonement (1QpHab 11.2-8).[10]

"הוי משקה רעיהו מספח חמתו אף שכר למען הבט אל מועדיהם" פשרו על הכוהן הרשע אשר רדף אחר מורה הצדק לבלעו בכעס חמתו אבית (= בבית) גלותו ובקץ מועד מנוחת יום הכפורים הופיע אליהם לבלעם ולכשילם (= להכשילם) ביום צום שבת מנוחתם

“Woe to the one who gives his neighbor to drink, adding in his poison, making him drunk, in order to gaze upon his feasts.” Its meaning concerns the Wicked Priest, who pursued the Righteous Teacher – to swallow him up (i.e., to kill him) with his poisonous vexation – to his house of exile, and at the end of the feast, (during) the repose of the Day of Atonement he appeared to them to swallow them up and to make them stumble on the fast day, their restful Sabbath.

The clash between the Jerusalem Wicked Priest and the Qumranite Righteous Teacher is likely alluded to in a hymn from among Hodayot:

… they conspired wickedly against me to exchange your Torah which you inculcated in my heart for smooth things (to deceive) your people. They withhold the drink of knowledge from the thirsty, but cause the thirsty to drink vinegar in order to gaze at their error (למען הבט אל תעותם, this alludes to the celebration of Yom Kippur at the wrong time, I.K.), to deport themselves foolishly on their festivals (להתהולל במעדיהם) and to be caught in their snare (1QH 12:5-12).[11]

The following emerges from 1QpHab 11.2-8:

A. Yom Kippur – Not the Same Day

The Yom Kippur of the “Wicked Priest” was on a different day than that of the Righteous Teacher. Otherwise, the former could not attack the latter, because of performing (or at least participating) in Yom Kippur rites in the Temple. Moreover, he would not have violated the sanctity of Yom Kippur by traveling approximately 50 km from Jerusalem to Qumran at the northwest corner of the Dead Sea, without any food and drink in the hot weather of the Judean desert. Thus, most likely the conflict refers to one of the controversies about observance of the biblical holidays in general and Yom Kippur in particular, in which the Qumran community found itself involved because of their solar calendar.[12]

It is also possible, however, as Sacha Stern suggests, that the Righteous Teacher and the Wicked Priest “could have reckoned the same lunar calendar, based on sightings of the new moon, except that on this occasion they happened to have sighted the new moon on different days; or alternatively, they may have differed on the question of whether to intercalate that year (with the addition of a thirteenth month), so that they would have observed the Day of Atonement, on that occasion, one month apart. Arguments such as these would not have meant that fundamentally different calendars were observed.”[13] If so, then the dispute between the Wicked Priest and the Righteous Teacher was regarding the reckoning of the calendar that year, rather than a dispute about a lunar versus a solar calendar.

B. Different Practices of Yom Kippur

The clash between the Wicked Priest and the Righteous Teacher may not have been only about the date of Yom Kippur but also about its nature. Naftali Wieder and later Joseph M. Baumgarten suggest that for the Sadducees and Pharisees, Yom Kippur was the day of fast, festival, and performing of a unique cult and rituals in the Temple, and had an ambivalent character, including happiness. Indeed, Mishnah Ta’anith 4:8 (and parallels in Talmud and Midrashim) states that “there were no happier fast days for Israel than the fifteenth of Ab and Yom Kippur.” For the Qumranites, however, it was the day of rest, fast, self-affliction and grief, and struggle with the demonic hosts of Belial. The assumption that the Qumranites’ Yom Kippur was a day of self-affliction and grief may be reflected in Jubilees 34:17-19; this book was very popular in Qumran as attested from the 14-15 copies of it found there.

Fighting about Yom Kippur has an impressive pedigree among ancient Jews. In addition to the story of the battle between the high priest and the righteous teacher, the Mishnah and Talmud (m. Rosh Hashanah 2:8-9; b. Rosh Hashanah 25a-b) tell a story about the head of Sanhedrin, Rabban Gamliel II of Yavneh (last quarter of the 1st cent. C.E.), and Rabbi Joshua ben Hananiah, who had a dispute about the calendar one year. In this story, Rabban Gamliel orders Rabbi Joshua to appear before him carrying his staff and money (which are forbidden to be carried on the holiday), on the day that according to Rabbi Joshua’s reckoning would be the Day of Atonement.

In the Talmudic story, Rabbi Joshua obeys Rabban Gamliel and peace is maintained. In contrast, according to the Dead Sea Scrolls, the high priest appeared in the camp of his opponent, the Righteous Teacher, and tried to impose his authority on him and his community. It is doubtful that the high priest succeeded, and the tremors of that confrontation fill the group’s scrolls and writings. At the core of both controversies is the centrality of Yom Kippur and the atonement Jews of all groups seek on this highest of high holidays.[14]

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

April 5, 2014

|

Last Updated

February 8, 2026

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Prof. Isaac Kalimi is Gutenberg-Forschungsprofessor in Hebrew Bible and Ancient Israelite History, at the Seminar für Altes Testament und Biblische Archäologie, Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz, Germany, and Senior Research Associate in the University of Chicago, USA. He received his Ph.D. from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Kalimi is the author of The Reshaping of Ancient Israelite History in Chronicles and The Retelling of Chronicles in Jewish Tradition and Literature: A Historical Journey.

Essays on Related Topics: