Edit article

Edit articleSeries

Our Mummified Patriarchs: Jacob and Joseph

Burying the Body of Joseph, illustration from the 1890 Holman Bible (colorized)

The end of Genesis tells the story of Jacob’s death and burial. As Jacob dies in Egypt, but wishes to be buried in Canaan, in the cave where his ancestors (and wife) had been buried, Jacob’s son Joseph, an Egyptian official at the time of Jacob’s death, has his servants embalm his father’s body. This would have kept it from decaying during the long journey, probably using an Egyptian practice we call mummification. Though the preservation of the body through the elimination of fluids after death is not exclusive to ancient Egypt, the word “mummy” or the image of a wrapped body, often with its arms crossed over the chest, invariably calls Egypt to mind.

Mummification is best viewed as a two-part practice:

- A physical process of drying out the body so it wouldn’t be susceptible to decay.[1]

- The expression of complex religious beliefs.

Part 1

The Physical Process

Mummification was an inconsistent practice—it would have varied a lot from period to period and, maybe, from case to case. No Egyptian source completely outlines exactly what was done in what order, or for how long (Egyptologists would go crazy if some text were found that detailed this process). Thus, it is important to read what follows as a description of the general outlines of the ideal process as best as we can reconstruct it.

The Viscera

The mummification process began with the removal of internal organs that were prone to decomposition. The viscera were mummified and typically buried with the dead in dedicated “canopic” jars. The jars of royals like Tutankhamun could be topped with the likeness of the deceased, but those of non-royal elites often bore the likenesses of the so-called sons of Horus:

- Imsety, a human who protected the liver;

- Duamutef, a jackal, who protected the stomach;

- Hapy, a baboon, who guarded the lungs;

- Qebsenuef, a falcon, who protected the intestines.

In some periods the preserved organs were returned to the body cavity, and yet the deceased was still buried with “dummy” canopic jars bearing the heads of these gods. Whether dummies or containing organs, the jars were often stored in a chest and interred alongside the mummy. Sometimes these chests bore the images of four protective goddesses: Isis, Nephthys, Neith, and Serket. Enshrining these organs, both physically and with the protections of so many deities, indicates an understanding that the viscera were essential to bodily function.

The Brain

The brain, on the other hand, was disposed of by hooking it through the nose, sometimes after it had been liquefied by pulverizing it with the hook. To do this, the nose was broken—this is the gory-sounding part of the process that usually appeals to schoolchildren.

The Heart

Most important to the Egyptians was the heart, which would ideally remain with the body. To ensure its survival, an amulet in the shape of the hieroglyph for “heart” might be placed within the burial assemblage. Sometimes this amulet was in the shape of a scarab beetle, inscribed with instructions for how to successfully use the heart to gain entry into the afterlife.

Timing

The Torah describes the process of embalming as taking forty days, with a seventy-day mourning period.

וַיִּמְלְאוּ לוֹ אַרְבָּעִים יוֹם כִּי כֵּן יִמְלְאוּ יְמֵי הַחֲנֻטִים וַיִּבְכּוּ אֹתוֹ מִצְרַיִם שִׁבְעִים יוֹם.

It required forty days, for such is the full period of embalming. The Egyptians bewailed him seventy days.

This fits the description of the process in Egyptian sources according to which the body was packed with salts and drained for around forty days to dry it, followed by a thirty-day period during which the body was subject to applications of unguents, oils, and various other treatments.

Nevertheless, some early modern commentaries have questioned the Torah’s description of the timing based on other ancient sources. This spurred the 19th century Jewish commentator, Samuel David Luzzatto (Shadal, 1800-1865), to defend the Bible’s accuracy:

לחנוט את אביו: היו מוציאים מגופו של מת המוח והמעים, והיו ממלאים את הבטן מר וקציעה, ואח”כ היו מולחים כל הגוף בנתר (nitrum) משך ארבעים יום, והירודוט אומר שבעים יום, ודיאודורוס אומר יותר משלשים יום, ואין ספק שהיה הדבר הזה ידוע לישראל ולמשה יותר ממה שהיה ידוע ליונים.

“To embalm his father” – they would remove from the dead body the brain and the innards, and would fill the stomach with herbs and spices, and afterwards they would salt the body with nitrum for forty days. Herodotus says seventy days, and Diodorus says more than thirty days. And there is no doubt that this practice was known among the Israelites and to Moses better than it was known to the Greeks.

Ideal versus Real Process

Debating, or even establishing, the precise sequence of mummification and the length of the mourning period may be impossible. Ancient performative practices most likely come to us as constructed ideals. Things weren’t always done in an official order, or in an exact time frame, or sometimes at all. Timing and—especially—resources dictated how embalming was carried out.

Mummification was for the highest elites, and the preservation quality of mummies varies wildly, so that some bodies, like those of the New Kingdom rulers, look eerily lifelike, while others have all but disintegrated. Some early pre-dynastic “mummies” were not subject to any of these interventions. In other periods, “good” or expensive burials incorporated so much pouring and applying of unguents and oils that the body was ultimately less well preserved.

Mummy Boards

In the Third Intermediate Period (around 1070-712 BCE)—arguably the golden age of mummification—the preservation practice became much more complicated. Bodies from this period often appear to have been “sculpted,” their features packed with linen or otherwise manipulated. In the same epoch the burial practice shifts from emphasis on the tomb to emphasis on the burial assemblage, that is, the goods physically surrounding the mummy.

Already at the end of the New Kingdom (1550-1070 BCE), a plank of wood bearing an image of the deceased was in use. These “mummy boards” appear to have become a canonical element of the burial assemblage by the Third Intermediate Period. Within the coffin, the board physically rested atop the mummy as another protective layer for the body.

Despite the adjustment in practice, the unifying principles that justified mummification are theoretically consistent across Egyptian history. Mummification was a process of transformation—the dead body was ideally changed from vulnerable and subject to decomposition to hard and easily preserved, like a statue. Conceptually, the living person became not a god, but divine nevertheless.

Wrappings and Coffins

In advance of burial, the mummy was packed with and wrapped in linens, along with amulets and, sometimes, what we call a “death mask.” The gold death mask of King Tut is the best-known of these, though masks of lesser status were gilded or painted yellow to represent gold. The skin of the gods was gold, and adorning the body with it was one more way of transforming the deceased into the divine. The body was placed in a coffin or series of coffins and processed to the tomb, where it would remain forever so that the metaphysical aspects of the self could return to the tomb and the body.

In very elite burials, the coffin(s) containing the wrapped mummy were placed within a sarcophagus incised with various texts that guided the deceased through the afterlife. Coffins were most often made of local woods like acacia or fig, which were thought to be sacred to the regenerative goddess Hathor, another symbol of rebirth and transformation. The sarcophagus, though, was ideally hard stone, which was protective—or it was meant to be, at least.

Sacred Burial Chambers and Tomb Robbers

Ideally, no one would ever again breach the burial chamber, but in the tomb chapel, the family would continue to nurture their loved one with prayer and food, caring for their revered ancestor for eternity.

Nevertheless, the deceased cannot be remembered, let alone nurtured, forever. Tomb robbery in Egypt is well-attested, and some tombs in the Theban necropolis were used and reused multiple times, sometimes by descendants but often by unrelated people just looking for a place to be laid to rest. High-status objects in tombs were often reused by, and sometimes redecorated for, whoever acquired them.

Modern Treatment of Mummies

Few Egyptian burials are found undisturbed, and many of the mummies that survived antiquity were treated like property by modern Europeans, especially in the 19th century. They were believed to contain hidden gems (sometimes true) and secret powers (always false). Mummies were unwrapped in front of audiences, burned for fuel, or ground up and consumed as medicines.

Mummies are ubiquitous in museum collections, where they are frequently on display, inspiring debates over how much personal dignity belongs to the dead. Would he or she have delighted to be remembered, or despaired at being gawked at? Does educating visitors about Egyptian beliefs justify exploitation? Can someone who died millennia ago, without an emotional response to current circumstances, be exploited? Almost everyone now agrees that mummies deserve to be treated respectfully, although there is no consensus on what constitutes respectful treatment.

Despite the prevalence of mummies and their close association with ancient Egypt, their indeterminate status—dead but “reborn,” neither person nor object—makes them liminal, and they can defy both neat categorization and rationalization. Mummies are dead bodies, after all, and few things trigger emotional reactions in people like physical manifestations of mortality.

Part 2

The Beliefs that Underpin Mummification

Egyptian burial practices were part of the mourning process of the living. They were also meant to ensure that the person’s self would continue in some state after the death of the body.

In Egyptian thinking, a person’s self was made up of multiple parts. Though there is no exact English translation for the following terms, these parts of the self can be defined as follows:

- The ba bird, which was something akin to the psyche or personal autonomy of the deceased.

- The ghostly akh, close to our concept of a “spirit” that functions as an intermediary between the living and the dead; the akh could punish those who wronged it or interfered in its tomb, or help the living if so inclined.

- The active ka, which required sustenance in the form of offerings and tomb goods.

Embalming—indeed, the entire Egyptian funerary practice—was intended to create a series of vessels in which these aspects of the deceased’s self were able to manifest. Images of the deceased, particularly statues, could house the akh, the ba, and especially, the ka in the event that the body became desecrated or otherwise inaccessible.

Metaphorical Vocabulary

In Egyptian language, the vocabulary for some of the actions of mummification bore metaphorical or theological weight. For example, the word for scent, sntr, contained the word for a deity—ntr. Applying a smelly unguent to a mummy, therefore, might have symbolized that the deceased was coming closer to the divine, or now divine himself/herself.

Likewise, the Egyptian term for “pouring” was related to the term for “ejaculation.” In Egyptian mythology, the first step in creation was the ejaculation of the creator god, Atum.[2] This concept, of course, mimics the first step of procreation in reality. So it may have been believed that pouring things on or into the cadaver would help the dead to become reborn.

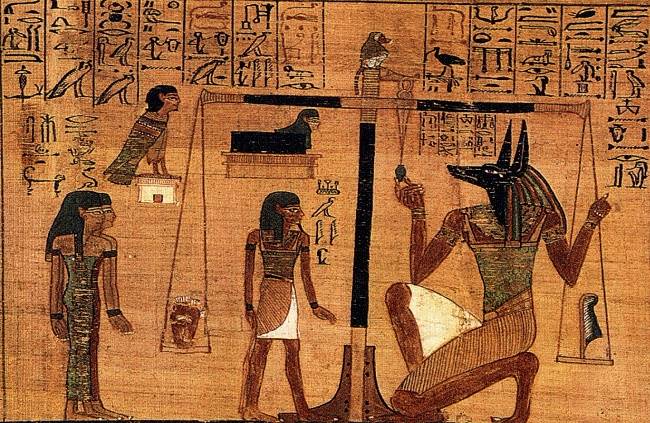

The Weighing of the Heart

Egyptian liturgy depicts the heart as the record of the person’s attitude and deeds, which is why its preservation as part of the body plays such a central role in mummification. The deceased was believed to need that record in the Underworld to prove that he or she deserved to be there. Funerary papyri and, sometimes, coffins depicted Chapter 125 of the Book of the Dead—the weighing of the heart against an ostrich feather, which was a symbol for maat, the concept of rightness in Egyptian society.[3] If the heart balanced against the feather on the scale, the deceased was able to enter the Afterlife. If not, the person would cease to exist.

The Cycle of Life, Death, and Rebirth

Egyptian society held multiple theologies at any given time, but among the more prominent was the construction of life, death, and rebirth as a cycle of the son becoming the father, and in turn dying and being reborn as the son. Ideally, offices, including that of king, passed from father to son. In tomb scenes, children make offerings to their seated, deceased parents; statues of mother/father/offspring triads attest to the importance of this generational cycle. Likewise, the king’s kawas thought to pass from each ruler to his or her successor, as if from father to son, whether the new king was a blood relation or not.[4]

A God of the Dead: The Mummified Osiris

In art and literature, this father-son cycle is represented by Osiris, the mythical ur-king of ancient Egypt, who was deposed, only to have his son, Horus, eventually assume the throne.[5] The concept of mummification is crucial to this cycle. In the myth, Osiris’ wife Isis, effectively mummifies Osiris’ recovered body. Osiris becomes a mortuary god while his son Horus rules as a living king. The funerary liturgy in the Third Intermediate Period (around 1070-712 BCE) increasingly emphasizes the deceased as an “Osiris.”

Throughout Egyptian history, Osiris is depicted as a mummy. His skin is sometimes bluish, blackish, or greenish—all colors that represent rebirth and regeneration, symbolically and linguistically, and which contrast visually with the reddish skin of living, virile Egyptian men. In comparison, Osiris is markedly corpselike, his body bound so tightly that his hands just emerge from the wrappings.[6]

The Story of Sinuhe and the Need to Be Buried in Egypt

Genesis describes Jacob and Joseph as concerned that their bodies would be left in Egypt. Both explicitly stipulate that their mummified corpses must be brought to Canaan and buried there.

Jacob (Gen 49:29)

בראשית מט:כט וַיְצַו אוֹתָם וַיֹּאמֶר אֲלֵהֶם אֲנִי נֶאֱסָף אֶל עַמִּי קִבְרוּ אֹתִי אֶל אֲבֹתָי אֶל הַמְּעָרָה אֲשֶׁר בִּשְׂדֵה עֶפְרוֹן הַחִתִּי.

Gen 49:29 Then he instructed them, saying to them, “I am about to be gathered to my kin. Bury me with my fathers in the cave which is in the field of Ephron the Hittite.

Joseph (Gen 50:25)

בראשית נ:כה וַיַּשְׁבַּע יוֹסֵף אֶת בְּנֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל לֵאמֹר פָּקֹד יִפְקֹד אֱלֹהִים אֶתְכֶם וְהַעֲלִתֶם אֶת עַצְמֹתַי מִזֶּה.

Gen 50:25 So Joseph made the sons of Israel swear, saying, “When God has taken notice of you, you shall carry up my bones from here.”

The Middle Kingdom story of Sinuhe, probably written around 1875 BCE, offers a parallel perspective, with an Egyptian protagonist with the inverse problem. The story details the wanderings of a man named Sinuhe outside of his homeland, Egypt.[7] Ultimately, Sinuhe has to return to Egypt in order to be properly buried—which is to say, mummified—which implies that that proper burial practices could only be executed within Egypt’s borders.

The text is loosely in the style of a tomb autobiography—that is, a story from the perspective of the deceased explaining that he served the king and the gods. A link is created between Egyptianness, so to speak, and mummification. The king invites Sinuhe back to Egypt proper specifically to die there so that his body can be subject to mummification (called “passing to blessedness”) and buried in a tomb bestowed by the king himself:

A night vigil will be assigned to you, with holy oils; /

And wrappings from the hands of Tayet. /

A funeral procession will be made for you on the day of joining the earth, /

With a mummy case of gold.[8]

The story begins with Sinuhe narrating from the tomb and ends where it began, echoing the cyclical continuity around which Egyptian thought was constructed: Sinuhe begins the story from death, is reborn within the text, and dies at the end of his journey, presumably to be reborn again.

The completion and repetition of this cycle is only possible because he has returned to Egypt and been mummified and buried, and this privilege was only extended to him because, in his travels, he remained essentially Egyptian. As the king tells Sinuhe in imploring him to come home,

Your death will not happen in a foreign country; /

Asiatics will not lay you to rest.[9]

Although we cannot apply one work of Egyptian literature broadly to a practice with millennia of history, the number of copies preserved of this tale suggests that it is expressing something universal about Egyptian belief: Over two dozen copies of the text survive from both the Middle Kingdom and later.[10]

Reading Sinuhe together with the Bible loosely suggests that place of origin was an important part of individual identity in the ancient Near East.[11] Both Sinuhe on one hand and Jacob and Joseph on the other worry that something important about themselves will be lost—perhaps the quality of their afterlife or their place in the destiny of their descendants—if they are not buried in their homelands.

Jacob and Joseph as Egyptian Ideals

Bereshit is ultimately a story of generations. Arguably, its defining literary theme is anxiety about the successful transition from father to son. Mummification, and Egyptian funerary traditions generally, were cultural responses to that same anxiety. Jacob’s story in particular revolves around securing a place as his father’s heir and, later, furthering that legacy thirteenfold.

One of the tenets of Egyptian kingship is to continually surpass the deeds of one’s predecessors: to do “never had the like occurred”; to enlarge and, therefore, to strengthen; to add to and enhance the works of rulers past. It may be ironic that, as he is mummified and returned to the resting place of his ancestors, Jacob has become, in death, an ideal Egyptian.

The account of Jacob’s death and burial is in keeping with the world he is pictured as inhabiting. Embalming may have been a pragmatic solution to the problem of physical decay, but the image of an Israelite patriarch going through an Egyptian ritual process is almost poetic in reinforcing the notion of a transnational ancient Mediterranean world.

The image is even more striking with Joseph, who not only has himself embalmed but even has his body placed in an Egyptian coffin as it awaits its final burial in Canaan, something he did not do for Jacob. And this is the final verse of the book of Genesis!

בראשית נ:כו וַיָּמָת יוֹסֵף בֶּן מֵאָה וָעֶשֶׂר שָׁנִים וַיַּחַנְטוּ אֹתוֹ וַיִּישֶׂם בָּאָרוֹן בְּמִצְרָיִם.

Gen 50:26 Joseph died at the age of one hundred and ten years; and he was embalmed and placed in a coffin in Egypt.

Genesis begins with the creation of the world (ch. 1), describes the beginnings of humanity (chs. 2-3), and even the origins of all the nations of the world (ch. 10) before turning its attention to Abraham and the Israelites. And it ends with the mummification of the patriarch from which the name Israel arises and his favorite and most important son, Joseph. These same mummified patriarchs are then buried in their homeland; Jacob in the cave of Machpelah (Gen 50:13) and Joseph, hundreds of years later, in Shechem (Josh 24:32).

This cosmopolitan image of Israelite founders with hybrid identities shows that ancient people lived, as we do, as citizens of a complex world in which matters of identity are not straightforward, consistent, and easily resolved.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

January 10, 2017

|

Last Updated

April 14, 2024

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Footnotes

Dr. Rachel P. Kreiter earned a doctorate in art history from Emory University in December 2015 and has written about arts and culture for various publications, including Burnaway and the Awl. Their research interests include ancient Egypt in its myriad contexts, including the African continent, ancient Near East, contemporary art, and museums.

Essays on Related Topics: