Edit article

Edit articleSeries

Poetic Laws

Beginning of Kedoshim in the Lisbon Bible, vol 1 (of 3). The manuscript was copied by Samuel, son of Samuel Ibn Musa, for Joseph, son of Judah al-Hakim, and was completed in 1482.

Rules for Reading Haiku

In arguably the most famous Japanese poem ever written, Matsuo Bashō writes,

An old silent pond…

A frog jumps into the pond,

splash! Silence again.[1]

Is this poem a simple, even funny, observation? Does the frog represent something, like the coming spring? Does the pond symbolize the universe, or is the pond just a pond? This poem is a haiku, a Japanese form of short poetry that typically contains lines of seventeen syllables divided into three phrases of 5 – 7 – 5. A haiku often juxtaposes two ideas and, somewhat jarringly, cuts between them suddenly. The static, quiet lake is disrupted by the active, lively frog, and the reader can sense the drama this movement creates.

Without knowing to look for this tension, a reader might miss the poetry’s hidden depths; the poem is not only about a frog that once jumped into water. Understanding the rules of how a haiku operates allows the person reading or hearing the poem to unlock the meaning and purpose of the poem.

Biblical Hebrew Poetry

Approximately one-third of the Hebrew Bible is poetic, and like most poetry, biblical Hebrew poetry operates according to its own set of culture-specific rules.

Lamech’s Poetic Lament

For example, in Gen. 4:23b, Cain’s descendant Lamech says,

כִּי אִישׁ הָרַגְתִּי לְפִצְעִי

וְיֶלֶד לְחַבֻּרָתִי.

I have slain a man for wounding me,

And a lad for bruising me.[2]

How many people has Lamech killed? Perhaps the answer is two: “a man” who wounded Lamech and “a lad” who bruised him. However, these words are written using a poetic device called parallelism, and a reader must be familiar with the rules of biblical poetry to understand the verse correctly. Indeed, Lamech has only killed a single person, though he describes the incident twice, using slightly different words.

The two clauses taken together (“I have slain a man for wounding me” plus “And a lad for bruising me”) constitute a line of poetry. The clauses themselves are called cola (singular: colon). In parallelism, an author expresses a single idea in two (or more) successive cola, where the second colon echoes the first in terms of content and/or grammar. “The man” in the first colon (labeled A) is the same person as “the lad” in the B-colon; “wounding me” is parallel to “bruising me.”

|

|

When God Spurns

Consider next a verse in which YHWH says how he will punish the person who consumes blood (Lev. 17:10b):

|

וְנָתַתִּי פָנַי בַּנֶּפֶשׁ הָאֹכֶלֶת אֶת הַדָּם

|

A | I will set my face against the person who eats the blood; |

|

וְהִכְרַתִּי אֹתָהּ מִקֶּרֶב עַמָּהּ.

|

B | I will cut him off from among his people. |

In a conventional reading of this verse as prose, two events will befall the person who violates God’s will: YHWH will (A) notice the transgression (“set my face against”) and then (B) cause the person to be executed or driven (“cut off”) from the community.[3]

If we instead understand this verse as poetic, then B would echo A, and the line would convey only a single thought: if God spurns the offender in A-colon, then B is the natural consequence of A and not a separate action.[4] B would echo and second A, reformulating and emphasizing the consequence for consuming blood instead of introducing a second event.

In this short study, I hope to consider how biblical legal sections such as Lev 19 would change if we read some of its verses as poetic rather than as prose.

A Crash Course in Parallelism

Parallelism, the main feature of biblical poetry, expresses itself in multiple ways relating to a line’s meaning, grammar, word choice, and sound.[5]

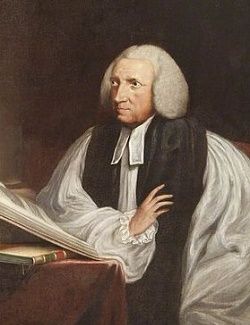

Modern study of biblical poetry began with Robert Lowth, an eighteenth-century British bishop and professor. In a series of lectures at Oxford University, he identified a phenomenon in biblical poetry where there exists “a certain equality, resemblance, or parallelism” between cola.[6] He identified three types of parallelism: synonymous (where the cola express the same idea using varied terminology, such as Lamech’s outcry in Gen. 4:23b), antithetical (where A and B convey contrary sentiments), and synthetic (a catchall category for poetic lines that are neither synonymous nor antonymic).

Heightening

In some poetic lines, the B-colon does not always parrot the A-colon. Rather, B can also heighten or specify A. For example, Isaiah 1:3a reads:

|

יָדַע שׁוֹר קֹנֵהוּ |

A B |

An ox knows its owner, And the donkey its masters’ trough. |

James Kugel argues that B goes further than A in its meaning. An ox is a relatively smart animal, so it should be little surprise that it can recognize its owner. It is more impressive, though, that a lowly donkey also knows where its food comes from. Kugel proposes translating some parallel sentences as “A is so, and what’s more, B is so.”[7] We could translate the verse as follows:

|

יָדַע שׁוֹר קֹנֵהוּ |

A B |

An ox knows its owner, And, what’s more, the donkey [knows] its masters’ trough. |

Grammar

In addition to their parallel meanings, cola may also show equivalence or variation in grammatical forms, such as when a masculine singular noun parallels a feminine plural noun. A perfect verb may parallel another perfect verb, an imperfect verb, a verbless nominal clause, and so on. These elements of Hebrew morphology and syntax may not always be perceptible in English translations.

Pairing

The 20th-century discovery of poetic epics from Ugarit helped biblicists understand that parallel lines also often contain certain fixed pairs of words; if A-colon mentions “silver,” B-colon will likely include “gold” (Ps. 68:14):

|

כַּנְפֵי יוֹנָה נֶחְפָּה בַכֶּסֶף |

A B |

The wings of a dove are covered in silver, Its pinions with fine gold. |

Biblical authors perhaps worked with oral (or, less likely, written) dictionaries containing hundreds of such word-pairs, similar to a lyric writer today consulting a rhyming dictionary.[8]

Alliteration and Assonance

Finally, a specific sound pattern might dominate parallel cola, producing alliteration (where similar consonants repeat), assonance (where similar vowels repeat), or, more rarely, end-rhyme. Notice the constant /a/ sound in Jer. 49:1b:

מַדּוּעַ יָרַשׁ מַלְכָּם אֶת־גָּד

וְעַמּוֹ בְּעָרָיו יָשָׁב.

maddûaʿ yāraš malkām ʾeṯ-gāḏ

wĕʿammô bĕʿārāyw yāšāḇ

Protecting a Disabled Individual

Parallelism may even affect the number of commandments in a verse. As is well-known, according to Jewish tradition the Torah contains 613 commandments (b. Makkot 23b). But how many of these are present in Lev. 19:14a?

לֹא תְקַלֵּל חֵרֵשׁ וְלִפְנֵי עִוֵּר לֹא תִתֵּן מִכְשֹׁל.

You shall not insult the deaf, and before the blind you shall not place a hindrance.

Read as standard prose, this law prohibits two specific acts: insulting the deaf and hindering the free movement of the blind. Indeed, while no official enumeration of the 613 exists, the Rambam (Maimonides) in Sefer Hamitzvot sees two separate prohibitions in this verse: insulting or cursing a Jew (Negative Commandment 317)[9] and giving misleading advice that hinders a person’s path (Negative Commandment 299).

Let us consider, though, that this verse might contain parallelism:

|

לֹא תְקַלֵּל חֵרֵשׁ |

A B |

You shall not insult the deaf, And before the blind you shall not place a hindrance. |

Indeed, many poetic texts present “blind” and “deaf” as word-pairs in parallel cola.[10]Further, if this verse were prose, the sentence could easily read, “Do not insult or hinder the deaf or the blind.”[11] Why did the author choose to separate the two impairments into two phrases? A parallel reading suggests that the author heightens the strictness of the statute in B-colon.

By the very nature of the disability, a deaf person would not likely be aware that any denigration had occurred. However, if a person places a physical obstacle (commonly “stumbling block”) in front of a blind person, the disabled individual, upon tripping or falling, would be fully aware of the event.

Thus, if the cola are taken as a parallel construction instead of as a two-itemed list, then a new translation is possible: “You shall not covertly insult the disabled behind their back (without their knowledge), / And, what’s more, you shall not overtly obstruct the disabled in their everyday life.” In this interpretation, Leviticus 19:14a can read as a strong, single prohibition against distressing or damaging disabled individuals in any way. I would therefore propose that only one of the 613 commandments should be found in this verse: you shall not mistreat someone with a disability.

Mourning Rituals

The same principle of parallelism can apply in Leviticus 19:27-28:

|

לֹא תַקִּפוּ פְּאַת רֹאשְׁכֶם

|

A | You shall not round off the side-growth of your head, |

|

וְלֹא תַשְׁחִית אֵת פְּאַת זְקָנֶךָ.

|

B | And you shall not destroy the side-growth of your beard; |

|

וְשֶׂרֶט לָנֶפֶשׁ לֹא תִתְּנוּ בִּבְשַׂרְכֶם

|

C | A gash for the dead you shall not make in your flesh, |

|

וּכְתֹבֶת קַעֲקַע לֹא תִתְּנוּ בָּכֶם.

|

D | And tattooed writing you shall not set on yourself. |

| אֲנִי יְהוָה | I am YHWH. |

If A and B are read as prose, then they contain two prohibitions about hair on two parts of the skull. Therefore, observant Jews do not shave their פֵּאוֹת (payot or peyis; sidelocks) even if they shave their beards. If A and B are read as parallel, with B echoing and perhaps heightening A, then the two cola convey only a single thought that a man shall not cut any hair on the side of his head (scalp or beard). Perhaps the traditional Rabbinic definition ofpayot (as discussed in b. Makkot 20a) is too narrow!

Similarly, if C and D are read as prose, then the verse prohibits two acts: cutting your flesh in mourning for the dead and tattooing any letters or symbols on yourself. If read as parallel, though, then the “tattooed writing” is a further explanation of the “gash for the dead.” (Even today, some people tattoo themselves with names or dates after a loved one dies.) If read as poetry, Leviticus 19:28 does not contain a blanket prohibition against tattooing, but only of tattoos undertaken in grief after a person’s passing. If all four cola parallel each other, then the prohibition against cutting hair might also only apply to mourning rituals, a notion substantiated by Deut. 14:1b, which only forbids shaving as a sign of grief:

לֹא תִתְגֹּדְדוּ וְלֹא תָשִׂימוּ קָרְחָה בֵּין עֵינֵיכֶם לָמֵת.

You shall not gash yourselves or create baldness between your eyes [shave your head] because of the dead.[12]

Interpreting Lev. 19:27-28 as poetic opens up a new realm of interpretation and might have significant ramifications for Jewish law, or at least for what this law meant in its pre-rabbinic interpretation.

Adultery

Numerous laws concerning prohibited sexual relations may also benefit from a poetic reading. Consider Lev. 20:10:

|

וְאִישׁ אֲשֶׁר יִנְאַף אֶת אֵשֶׁת אִישׁ

|

A | A man who commits adultery with the wife of a man, |

|

אֲשֶׁר יִנְאַף אֶת אֵשֶׁת רֵעֵהוּ

|

B | Who commits adultery with the wife of his neighbor, |

|

מוֹת יוּמַת הַנֹּאֵף וְהַנֹּאָפֶת

|

He shall be put to death, the adulterer and the adulteress. |

The verse is oddly repetitive, with “who commits adultery with the wife of…” present in both A and B. This unnecessary duplication has led some scholars to propose that the verse contains a scribal error called dittography, where a copyist mistakenly repeats a letter or phrase.[13] Alternatively, perhaps someone added B-colon to clarify a minor ambiguity in A: the NJPS translation renders אֵשֶׁת אִישׁ as “another man’s wife” instead of my hyper-literal “the wife of a man,” for surely a man does not commit adultery through sex with his own wife. Or, the expansion in B explicitly limits the law to adultery with an Israelite’s wife.[14]

However, we can already see that the author chose to use more words than necessary, as the Hebrew root נאף itself means “to commit adultery.” The phrase “with the wife of” is superfluous;[15] this law would convey the same information if it read אִישׁ אֲשֶׁר יִנְאַף מוֹת יוּמַת, “A man who commits adultery shall be put to death.” Thus, the repetitive nature of B-colon is little cause to hypothesize a corrupt or altered text. Instead, the repetition might be poetic.

Indeed, reading 20:10 as containing parallelism suggests that B heightens A by moving from the general crime of adultery to the specific crime of adultery with an Israelite woman: “A man who commits adultery with the wife of (another) man, and, what’s even worse, who commits adultery with the wife of his (Israelite) neighbor…”. The verse presents the single idea that adultery is a capital crime by having B reformulate and heighten A.

Poetry Versus Prose

No word for “parallelism” exists in Biblical Hebrew, and the Tanakh does not usually contain markings to indicate when poetry is present. How do we know when we should interpret a text as poetry and when as prose? In short, the scholarly consensus has already decided which texts are poetic. In many cases, centuries of brilliant religious and academic leaders have gotten it right. But, as our understanding of ancient texts continues to evolve, we may find still-unrecognized poetic passages.

I speculate here that the laws of Parashat Kedoshim contain more poetic elements than are first obvious, and I have elsewhere claimed that entire chapters of the Torah should be redefined as poetic.[16] However, many hypotheses concerning Torah composition—including mine—can never be proven. Instead, I hope that readers will continue to search for meaning in biblical texts with an open mind towards new interpretations, including the possibility that many more texts are poetic than meet the eye.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

May 1, 2017

|

Last Updated

January 8, 2026

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Dr. Jason Gaines is Senior Professor of Practice in Hebrew Bible, and Director of Undergraduate Studies for the Department of Jewish Studies, at Tulane University in New Orleans, LA. He received his Ph.D. in Near Eastern and Judaic Studies from Brandeis University, and is the author of The Poetic Priestly Source (Fortress Press).

Essays on Related Topics: