Edit article

Edit articleSeries

Symposium

Sacrificing a Lamb in Egypt

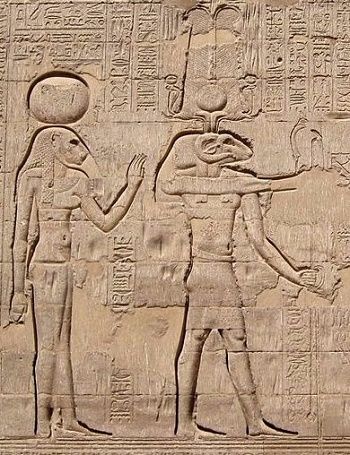

A scene at the Temple of Seti I. The King, presenting burning incense in front of the boat of Amun-Ra. The figure heads on the prow and stern are in the form of rams’ heads emerging from polychrome lotus flowers. Photo by kairoinfo4u, Flickr

Neither the Egyptian gods nor the Egyptian cult plays a very significant role in the book of Exodus. Only one passage briefly alludes to the worship of sacred animals, the most striking peculiarity of the Egyptian cult. Exod 8:22 (=26) mentions a ritual conflict between Hebrew and Egyptian beliefs, during which Moses objects to Pharaoh’s suggestion to hold the requested feast for the god of the Hebrews not in the wilderness, but in Egypt, with the argument that,

שמות ח:כב לֹ֤א נָכוֹן֙ לַעֲשׂ֣וֹת כֵּ֔ן כִּ֚י תּוֹעֲבַ֣ת מִצְרַ֔יִם נִזְבַּ֖ח לַי-הֹוָ֣ה אֱלֹהֵ֑ינוּ הֵ֣ן נִזְבַּ֞ח אֶת תּוֹעֲבַ֥ת מִצְרַ֛יִם לְעֵינֵיהֶ֖ם וְלֹ֥א יִסְקְלֻֽנוּ:

Exod 8:22 It would not be right to do so; for the sacrifices that we offer to the LORD our God are an abomination to the Egyptians. If we offer in the sight of the Egyptians sacrifices that are an abomination to them, will they not stone us?

This passage suggests that Moses recognizes that the Israelites are going to sacrifice an animal that is sacred to the Egyptians, and that this would be an abomination for the Egyptians (תועבת מצרים). Ostensibly, this is because the ram was the sacred animal of two Egyptian gods, Amun and Khnum.

Contempt for Amun

Amun was a very important god in Ancient Egypt, and in the New Kingdom (1550-1070 B.C.E.) he was seen as the king of the gods, and was syncretized with the sun god as Amun-Ra. It would doubtless have been offensive to the priests of Amun to sacrifice a ram, and there certainly were temples of Amun in the Delta in the vicinity of Goshen and the capital, Pi-Ramesse. That such an act would be offensive would have been clear to any educated person who knew about Egypt in ancient times. Herodotus, in his survey of Egyptian customs, writes (Histories, 2:42):

Now all who have a temple set up to the Theban Zeus (=Amun) or who are of the district of Thebes, these, I say, all sacrifice goats and abstain from sheep… the Egyptians make the image of Zeus (=Amun) into the face of a ram… the Thebans then do not sacrifice rams but hold them sacred for this reason.[1]

Centuries later, the Roman historian, Publius Cornelius Tacitus (56-ca.117 C.E.), who believes that Moses created the Torah laws to polemicize against Egyptians, even suggests that the Jews, “sacrificed rams for the sake of despising Amun (caeso ariete velut in contumeliam Hammonis).”[2]

The Khnum Temple in Elephantine

Khnum is the god who creates individual humans on his potter’s wheel; his worship goes all the way back to the old kingdom (3rd millennium BCE). As the ram was also sacred to the priests of Khnum, they too would not have looked fondly on sacrificing a sheep. We do not know if there were temples of Khnum in the delta, but we do know of Khnum temples in the south, on the islands of Esna and Elephantine.

In fact, Moses’ fear of a violent reaction is highly reminiscent of a well-documented case that occurred at the beginning of the 5th century on the island of Elephantine.[3] There, a Judahite temple of Yahu stood in closest vicinity of the Egyptian temple of Khnum. The fact that the ram was the sacred animal of Khnum may have sanctified all related animals, such as sheep and lambs, on Elephantine.

The sacrifice of lambs on the occasion of Pesach must have offended the priests of Khnum, for they took advantage of the temporary absence of the Persian satrap and had Egyptian soldiers destroy the Jewish temple. The Jews asked the authorities in Jerusalem for the permission to rebuild the temple and got it, with the exclusion of making ‘olah offerings, i.e., sacrifices that were burnt in their entirety to God, without the worshipper eating any part, doubtlessly in order not to repeat the offence in the future.[4]

The Strengthening of a Taboo under Foreign Rule

The worship of sacred animals is as old as Egyptian religion. Each of the major and many of the minor deities had their specific sacred animals. Although veneration of these animals was part and parcel of the cult from olden times, it assumed a new significance under foreign, i.e., Persian domination when the cult of the sacred animals became a matter of cultural-religious identity, not unlike cow worship in India under British colonial rule.

The mention of the תועבה or “abomination” (i.e., taboo in the sense of the most sacred, untouchable item) of the Egyptians seems to reflect this stage in the Persian era when the sacred animals achieved the highest status of sanctity in Egypt. In turn, this taboo would have been well-known in the Persian age, both to Greek writers like Herodotus and to the Jewish scribes in Jerusalem, who gave us the final form of the exodus story.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

April 18, 2016

|

Last Updated

February 9, 2026

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Prof. Jan Assmann, z”l, was a Professor of Egyptology at the University of Heidelberg and is now Honorary Professor of Cultural and Religious Studies at Constance. He received his Ph.D and Dr.habil from Heidelberg, as well as honorary degrees from Muenster, Yale and the Hebrew University Jerusalem. Among his many books are Moses the Egyptian; The Search for God in Ancient Egypt; The Mind of Egypt; Death and Salvation in Ancient Egypt; Of God and Gods; The Price of Monotheism; and From Akhenaten to Moses.

Dr. Rabbi Zev Farber is the Senior Editor of TheTorah.com at the Academic Torah Institute. He holds a Ph.D. from Emory University in Jewish Religious Cultures and Hebrew Bible, an M.A. from Hebrew University in Jewish History (biblical period), as well as ordination (yoreh yoreh) and advanced ordination (yadin yadin) from Yeshivat Chovevei Torah (YCT) Rabbinical School. He is the author of Images of Joshua in the Bible and their Reception (De Gruyter 2016) and co-author of The Bible's First Kings: Uncovering the Story of Saul, David, and Solomon (Cambridge 2025), and editor (with Jacob L. Wright) of Archaeology and History of Eighth Century Judah (SBL 2018). For more, go to zfarber.com.

Essays on Related Topics: