Edit article

Edit articleSeries

The Joseph Story: Ancient Literary Art at Its Best

Joseph explains Pharaoh’s dream. Artist: Adrien Guignet Frnace 1816 – 1854. Wikimedia

Coloring the Story with Egyptian Words and Customs

Like the exodus narrative (Exod 1-15),[1] the Joseph narrative is infused with Egyptian words, themes, religious concepts, and more. This is best seen in Genesis 41, where Egyptian words, proper names, and customs abound.[2]

Egyptian Words

Achu – This term אָחוּ appears in the cow dream (vv. 2 and 18). It derives from the Egyptian word 3ḫy, “reed-grass.”[3]

Abrech – When Joseph is paraded through the city, the people call out אַבְרֵךְ (v. 43). The term is a hapax legomenon, and while several etymologies have been proposed, the best, especially given the context, is Egyptian ib r-k, literally “heart to you,” presumably in the sense of “attention!”[4]

Egyptian Proper Names

Tzafenat Pa’anech –Pharaoh grants Joseph the Egyptian name צָפְנַת פַּעְנֵחַ (v. 45). The phrase is meaningless in Hebrew,[5] but it reads well as the Hebraized form of Egyptian dd p3 ntr iw-f ʿnḫ ‘the god says, he has life’.[6] Many readers will recognize the Egyptian word ʿnḫ, ‘life’ (anglicized as ‘ankh’) preserved in the final three consonants of the Hebrew phrase, that is, ע-נ-ח.

Asenat – Joseph’s wife’s name is אָסְנַת (vv. 45, 50), which derives from Egyptian n-s nt, “she who belongs to (the goddess) Neith.”[7] Names constructed in this manner are common throughout the history of ancient Egypt.

Potiphera – Joseph’s father-in-law is פֹּוטִי פֶרַע Potiphera” (v. 45), a name which derives from Egyptian p3 di p3 rʿ, “He whom Ra has given.”[8]

On – Potiphera is described as כֹּהֵן אֹן ‘priest of On’ (v. 45), Egyptian iwn (‘On,’ i.e., Heliopolis), the center of Ra worship in ancient Egypt.[9]

Egyptian Customs

Dream Interpretation – In ancient Egypt, dream interpretation was a valued art; in fact, we possess two extensive dream interpretation manuals from ancient Egypt.[10] The older and larger of the two manuals, dating to the reign of Ramses II (1279–1213 B.C.E.), includes a list of 222 items (139 good dreams, 83 bad dreams), with the proper interpretation. Thus, in schematic fashion, “If you dream x, then y shall occur,” and so on.[11] It is no surprise, accordingly, that the largest concentration of dreams and dream interpretation in the Bible takes place in the Joseph narrative: his own two dreams in ch. 37, the dreams of his two fellow prisoners in ch. 40; and the Pharaoh’s dreams in ch. 41.[12]

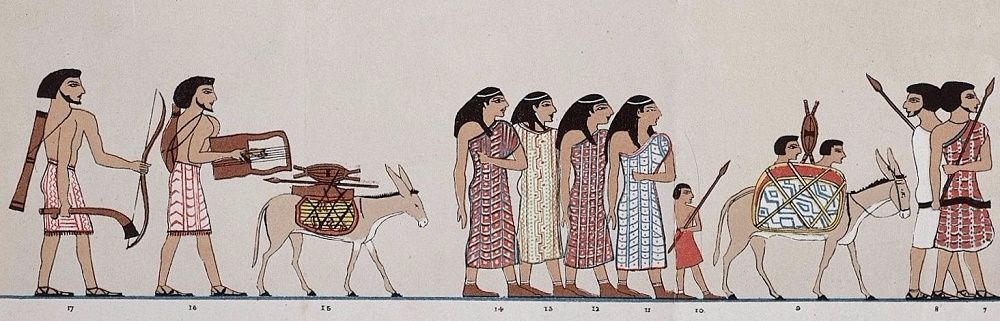

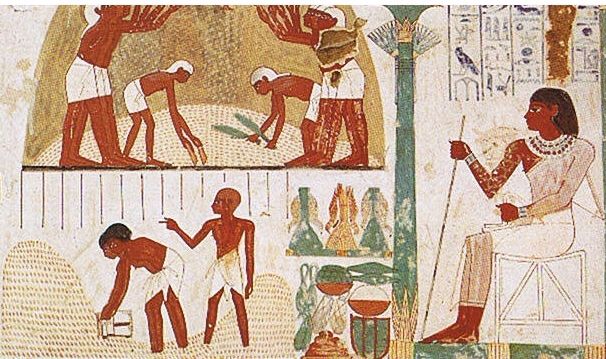

Shaving – In v. 14, Joseph shaves before his audience with Pharaoh. This reflects the fact that Israelite and other Semitic adult males wore beards, but the Egyptians were clean-shaven. Thus begins Joseph’s acculturation process, as he commences the transformation from a Hebrew lifestyle to an Egyptian one.

Attire – When Pharaoh elevates Joseph to the level of high government, he dresses him in appropriate Egyptian attire (41:42):

וַיָּ֨סַר פַּרְעֹ֤ה אֶת טַבַּעְתֹּו֙ מֵעַ֣ל יָדֹ֔ו וַיִּתֵּ֥ן אֹתָ֖הּ עַל יַ֣ד יֹוסֵ֑ף וַיַּלְבֵּ֤שׁ אֹתֹו֙ בִּגְדֵי שֵׁ֔שׁ וַיָּ֛שֶׂם רְבִ֥ד הַזָּהָ֖ב עַל צַוָּארֹֽו׃

And Pharaoh removed his signet-ring[13]from upon his hand, and he placed it on the hand of Joseph; and he dressed him (with) garments of linen,[14] and he placed a chain of gold upon his neck’.

Such is the dress of an Egyptian aristocrat, as many tomb paintings attest.

The infusion of Egyptian words and cultural traits into the Joseph narrative is not merely connected to the cultural and theological background of the Bible, but it also serves a literary purpose: By introducing words and ideas from the geographical setting of a particular story, the author transports the reader to that locale. And this is only one example of the literary artistry used by the biblical authors to craft the Joseph story.

The Bible works at different levels: theological, moral and ethical, historical, legal, political, and so on. But at the most basic level, it is literature, as scholars have increasingly noted over the past forty years.[15] Its authors were ancient Israelite literati who created a style of literary prose that is unsurpassed in antiquity. The Joseph story is the prime example of this prose style.

Interior Monologue

The Joseph story offers several clear examples of the Bible’s use of interior monologue, a frequent biblical stylistic device. Generally, the biblical narrator simply recounts the story. But from time to time, the author allows the reader to view the narrative not from his third-person objective stance, [16] but rather from the point-of-view of one or more of the characters.

A classic example of this device appears in Genesis 41:8,

וַיְסַפֵּ֨ר פַּרְעֹ֤ה לָהֶם֙ אֶת חֲלֹמ֔וֹ וְאֵין פּוֹתֵ֥ר אוֹתָ֖ם לְפַרְעֹֽה.

And Pharaoh related his dream to them [i.e., the magicians], but none could interpret them for Pharaoh.

The narrative describes two dreams, and the text informs us that Pharaoh awoke in between the dream about the cows and the dream about the grain (v. 4). But v. 8 subtly lets us know that Pharaoh understood that the two dreams were one by telling us that “Pharaoh related his dream” (in the singular). The magicians, however, were not perceptive enough to understand this point; to them there were two dreams and thus the text says, “none could interpret them.”[17]

The passage quoted above presents this point by stating “And Pharaoh related his dream to them,” thus allowing the reader a glimpse at Pharaoh’s perception of the matter; while in stating “but none could interpret them for Pharaoh,” the narrator has given us the magicians’ point-of-view.

This observation that the magicians did not perceive what Pharaoh knew is accomplished in a very oblique way, with the text gliding from the narrator’s voice to the point-of-view of characters in the story. This is done without direct quotations; thus, the term “interior monologue.”

The reader needs to retain this observation as she continues to absorb the story. True, Pharaoh says to Joseph “I dreamed a dream, and no one can interpret it” (v. 15), with both Joseph and the reader hearing this from Pharaoh’s mouth directly, and with two singular forms (‘dream’ and ‘it’) used. But this point is brought home in v. 25, when Joseph says, “Pharaoh’s dream is one” (v. 25).

What the magicians were unable to discern, Joseph realized very clearly. No doubt when Joseph began his interpretation of the dream(s) to Pharaoh in this manner, Pharaoh knew that he had found his man. Joseph was able to state explicitly what Pharaoh already knew: the dreams were one and the same.

Only the careful reader of this story, who had grasped the author’s intention with the words, “but none could interpret them for Pharaoh” (v. 8) as an interior monologue presenting the viewpoint of the magicians, can fully realize how Joseph truly surpassed the magicians in his ability to interpret Pharaoh’s dream(s).

Repetition with Variation

Repetition is one of the most important literary techniques in the Bible, and is especially prominent in the Joseph story.[18] The specific technique of repetition with variation is utilized with great mastery in the account of Pharaoh’s two dreams (41:1-7).[19] The narrator presents these two dreams to us in all their detail, but in dispassionate fashion, without commentary. Pharaoh then relates the dreams to the magicians of Egypt in summary fashion (41:8) without the readers of the story hearing this telling. Then Joseph arrives (41:14-16) and we hear a second telling of the dreams (41:17-24), this time from the mouth of Pharaoh as he addresses Joseph; this retelling is characterized by passion and personal commentary:

מא:יט לֹֽא רָאִ֧יתִי כָהֵ֛נָּה בְּכׇל אֶ֥רֶץ מִצְרַ֖יִם לָרֹֽעַ.

41:19 …I never saw such bad (cows) in all the land of Egypt.

מא:כא וְלֹ֤א נוֹדַע֙ כִּי בָ֣אוּ אֶל קִרְבֶּ֔נָה וּמַרְאֵיהֶ֣ן רַ֔ע כַּאֲשֶׁ֖ר בַּתְּחִלָּ֑ה…

41:21 …One would not know that they came into their midst, for their appearance was so bad, as it had been at the start…

This commentary is not present the first time the dreams were presented. We then are treated to a third telling of the dreams, in verses 25-27, or at least in part, because in the course of interpreting the dreams for Pharaoh, Joseph repeats elements of the report that he had just heard from Pharaoh.

Shifting Vocabulary

The specific vocabulary is altered in each retelling of the dreams. This technique of repetition with variation is typical of biblical storytelling; moreover, it works at two levels.[20] First, it allows the author to display his lexical and grammatical virtuosity; and secondly, it prevents the listener from tiring of hearing the same material over again.

The text was originally performed or presented orally, a fact which we must keep in mind at all times whenever reading ancient literature. The author wrote the text, but the presenter intoned the text orally for the listeners to hear aurally, and thus we should picture the story proceeding along the line of:

author > text > presenter > listener

The repetition with variation that the author places in the text demands the mind of the listener to constantly be at attention during the presentation.

The story of Pharaoh’s dreams has a number of prominent examples of this variation in language.

Cow Dream

Fat Cows Appear

| Narrator (41:2) |

יְפֹ֥ות מַרְאֶ֖ה וּבְרִיאֹ֣ת בָּשָׂ֑ר

|

beautiful of sight and fat of flesh |

| Pharaoh (41:18) |

בְּרִיאֹ֥ות בָּשָׂ֖ר וִיפֹ֣ת תֹּ֑אַר

|

fat of flesh and beautiful of form |

Note the change in the ordering of the two phrases and the substitution of מַרְאֶה (“sight”) with תֹּאַר (“form”).

Thin Cows Appear

| Narrator (41:3) |

רָעֹ֥ות מַרְאֶ֖ה וְדַקֹּ֣ות בָּשָׂ֑ר

|

bad of sight and thin of flesh |

| Pharaoh (41:19) |

דַּלֹּ֨ות וְרָעֹ֥ות תֹּ֛אַר מְאֹ֖ד וְרַקֹּ֣ות בָּשָׂ֑ר

|

gaunt and very bad of form, and meager of flesh |

Again, the word מַרְאֶה (“sight”) becomes תֹּאַר (“form”) in the second telling; the adverb מְאֹד “very” is added; Pharaoh leads with the word דַּלֹּות (“gaunt”) absent from the narrator’s account; and instead of דַקֹּות (“thin”) he uses the graphically similar רַקֹּות (“meager”). And then to all of this Pharaoh adds the expression noted above, “I never saw such bad (cows) in all the land of Egypt.”

Thin Cows Eat Fat Cows

| Fat Cows | Thin Cows | |||

| Narrator (41:4) |

יְפֹ֥ת הַמַּרְאֶ֖ה וְהַבְּרִיאֹ֑ת

|

beautiful of sight and fatty |

רָעֹ֤ות הַמַּרְאֶה֙ וְדַקֹּ֣ת הַבָּשָׂ֔ר

|

bad of sight and thin of flesh |

| Pharaoh (41:20) |

הַבְּרִיאֹֽת

|

fat |

הָרַקֹּ֖ות וְהָרָעֹ֑ות

|

meager and bad |

The narrator’s description of the cows is almost, but not quite, the same as his description of the cows when they appear. For the good cows, he merely leaves out the word בָּשָׂר (“meat,” see 41:2). For the bad cows, he repeats the same phrases (41:2), though with the addition of the necessary definite article ‘the’ (2x).[21] Here, too, I would argue, we have a literary flourish: a) the narrator departs from the technique of repetition with variation, in order to keep the reader/listener honest, as it were; and b) the bad cows are so striking to Pharaoh, that their description is constant, at least in vv. 3-4.

Variation returns when Pharaoh relates the dream to Joseph, for he now refers to the bad cows as “meager and bad” and the good cows as simply “fat,” at which point he adds the expression noted above, “One would not know that they came into their midst, for their appearance was so bad, as it had been at the start.”

Grain Dream

The retelling of the grain dream offers fewer examples of stylistic variation, but the technique continues to be employed nonetheless.

Appearance of Good Ears-of-Grain

| Narrator (41:5) |

בְּרִיאֹ֥ות וְטֹבֹֽות

|

fat and good (41:22) | ||

| Pharaoh (41:22) | מְלֵאֹ֥ת וְטֹבֹֽות | full and good |

The description of the good ears-of-grain is already shorter than that description of the cows, using only two words instead of four, and Pharaoh changes one of them in his retelling to the word used by the narrator in the dream’s next scene.

Appearance of Bad Ears-of-Grain

| Narrator (41:6) |

דַּקֹּ֖ות וּשְׁדוּפֹ֣ת קָדִ֑ים

|

thin and blasted by the east-wind |

| Pharaoh (41:23) |

צְנֻמֹ֥ות דַּקֹּ֖ות שְׁדֻפֹ֣ות קָדִ֑ים

|

shriveled, thin, blasted by the east-wind |

Here, Pharaoh expands the wording by adding the new lexeme צְנֻמֹות (“shriveled”), a hapax legomenon in the Bible. At the same time, he varies the grammar by not using the conjunction “and” as one would have expected.

Bad Ears-of-Grain Swallowing Good Ears-of-Grain

| Good | Bad | |||

| Narrator (41:7) |

הַבְּרִיאֹ֖ות וְהַמְּלֵאֹ֑ות

|

fat and full |

הַדַּקֹּ֔ות

|

thin |

| Pharaoh (41:24) |

הַטֹּבֹ֑ות

|

good |

הַדַּקֹּ֔ת

|

thin |

In the swallowing scene, the narrator refers to the good ears-of-grain as “fat and full”; the change in the latter term (from “good” to “full”) is the same as what Pharaoh uses when he retells the appearance of the good ears-of-grain. The narrator’s description of the bad ears-of-grain as simply “thin,” is itself quite “thin,” as it omits the phrase “blasted by the east-wind.”

When Pharaoh relates this scene to Joseph, he abridges both descriptions, as the good ears-of-grain are simply “good.” The bad ears-of-grain he describes simply as “thin,” like the narrator does.

These shortenings suggest that Pharaoh is a bit tired by this point, as he approaches the end of his long speech (vv. 17-24), and so he uses only single adjectives to describe the contrasting ears-of-grain.

Joseph’s Interpretation

As the story proceeds, Joseph refers to the cows and the ears-of-grain with yet different terms and phrases!

Good Cows and Ears-of-Grain – Joseph keeps it simple in the beginning, by referring to the good cows as simply הַטֹּבֹ֗ת ‘good’ (v. 26) and to the good ears-of-grain in similar fashion as simply הַטֹּבֹ֔ת ‘good’ (v. 26). Pharaoh used this word to refer to the good ears-of-grain only (v. 22 – see above), but Joseph applied it to both sets of good items.

Bad Cows and Ears-of-Grain – Joseph continues in the next verse by referring to the bad cows as הָֽרַקֹּ֨ות וְהָרָעֹ֜ת (“meager and bad” 41:27), which is verbatim what he heard from Pharaoh (v. 20 – see above).[22] When he refers to the bad ears-of-grain, however, Joseph introduces a new lexeme: הָרֵקֹ֔ות שְׁדֻפֹ֖ות הַקָּדִ֑ים (“empty and blasted by the east-wind” 41:27). Moreover, since the words רַקֹּ֨ות (“meager”) and רֵקֹ֔ות (“empty”) sound so much alike (and indeed they are written the same way), the listener may think for a moment that the presenter has misspoken, or that she has misheard the word, but such is the stuff of biblical literature: minor lexical substitutions such as this one serve as one of the key building blocks from which the text is constructed.

The Role of the Listener

Considering that this literature was meant to be read out loud to a listening audience, are we to assume that the listener was supposed to keep track of all these small changes in language? Would it even be possible?! Apparently, yes. Such was the ability of the ancient listener, raised in a culture in which literature was presented orally and was consumed aurally.

The language was an integral part of the narrative, so that, to repeat, here and elsewhere the author grasped the opportunity to display his virtuosity, and he had every expectation that his reader/listener would be able to apprehend these minor lexical and stylistic alternations.

Literary Artistry in Biblical Prose

The author of our text uses every opportunity to enhance the literary pleasure. The reader is transported to Egypt itself through the inclusion of Egyptian words, proper names, and customs, is invited to enter the mind of the character (in this case, especially Pharaoh), through the use of inner monologue, and is encouraged to analyze a dizzying array of repetition with variation. The combined effect yields one of the greatest works of biblical narrative prose, the Joseph novella.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

December 11, 2017

|

Last Updated

February 8, 2026

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Prof. Gary Rendsburg serves as the Blanche and Irving Laurie Professor of Jewish History in the Department of Jewish Studies at Rutgers University. His Ph.D. and M.A. are from N.Y.U. Rendsburg is the author of seven books and about 190 articles; his most recent book is How the Bible Is Written.

Essays on Related Topics: