Edit article

Edit articleSeries

Tikvatenu: The Poem that Inspired Israel’s National Anthem, Hatikva

Avital Pinnick/flickr cc.20

The History of Hatikva and Its Author

Naftali Herz Imber (1856-1909), the author of the poem on which Israel’s national anthem is based, was born in 1856 in a small town in Galicia, at that time part of the Austrian Empire. From a young age, he wrote songs and poems, including a poem dedicated to Emperor Franz Josef, for which he received an award from the emperor.[1]

Naftali Herz Imber (1856-1909), the author of the poem on which Israel’s national anthem is based, was born in 1856 in a small town in Galicia, at that time part of the Austrian Empire. From a young age, he wrote songs and poems, including a poem dedicated to Emperor Franz Josef, for which he received an award from the emperor.[1]

At age 19, he left his native town and began to travel across Europe and beyond. During his travels in Turkey, he met British diplomat Sir Laurence Oliphant in Istanbul. Oliphant, who hired Imber to be his personal secretary, was an author and a Christian messianic mystic who enthusiastically supported the return of Jews to Eretz Yisrael. Imber accompanied Sir Oliphant and his wife Alice to Eretz Yisrael and stayed there with them from 1882-1887, years that coincided with the First Aliyah (the first major wave of European Zionist immigration to what is now Israel between 1882 to 1903).

Contemporary sources relate that Imber was a colorful character who loved to sing and visit the various agricultural communities founded by the immigrants. After he had eaten and drunk to his heart’s content, he would read his poems. The flowery and emotionally charged words were embraced by the builders of the moshavot (Jewish agricultural settlements) and expressed their deepest sentiments and hopes. Imber ultimately left Eretz Yisrael, moving first to London and then to New York, where he died penniless in a public hospital in 1909.

The Original Poem: Tikvatenu

Imber apparently composed Hatikva (The Hope) around 1878, several years before he moved to Eretz Yisrael. At first the poem was called Tikvatenu (Our Hope), and had nine stanzas (only two would become the Israeli national anthem). Tikvatenu was published in Barkai, a book of his poems, in Jerusalem in 1886. Hatikva, the two stanzas that became the national anthem, were revised several times over the years, including by Imber himself. Since he read different versions at the moshavot he visited, the result was that the members of the various moshavot were familiar with different versions of the poem.

Hatikva Gets a Tune

In addition to the flowery and uplifting words, the tune helped this poem become ingrained in the hearts and minds of its listeners. A few tunes were adapted for this poem. The one that is familiar to us today was written by Shmuel Cohen,[2] a young man who made aliyah from Romania.

Hatikva Overtakes the Competition

Hatikva was the most popular song that reflected the Zionist hopes and yearnings. Several other songs, particularly one by Chaim Nachman Bialik, who is considered Israel’s national poet,[3] and Psalm 126 (שיר המעלות בשוב י־הוה), were candidates for the anthem for the Zionist movement and later for the State of Israel, but Hatikva ultimately won the people’s hearts.

The Official Version of Hatikva: A Revised Form of the First Two Stanzas

Only two of the original nine stanzas of Tikvatenu comprise Israel’s national anthem, and even these were revised a few times, including reversing the order of the stanzas. The following is the official version of Hatikva as it appears in the Israeli Flag and Emblem Law:

כּל עו̇ד בַּלֵּבָב פְּנִימָה

נֶפֶשׁ יְהוּדִי הוֹמִיָּה

וּלְפַאֲתֵי מִזְרָח קָדִימָה

עַיִן לְצִיּוֹן צוֹפִיָּה.

As long as in the heart within,

The Jewish soul yearns,

And toward the eastern edges, onward,

An eye gazes toward Zion.

עוֹד לֹא אָבְדָה תִּקְוָתֵנוּ

הַתִּקְוָה בַּת שְׁנוֹת אַלְפַּיִם

לִהְיוֹת עַם חָפְשִׁי בְּאַרְצֵנוּ

אֶרֶץ צִיּוֹן וִיְרוּשָׁלַיִם.

Our hope is not yet lost,

The hope that is two thousand years old,

To be a free nation in our land,

The Land of Zion, Jerusalem.[4]

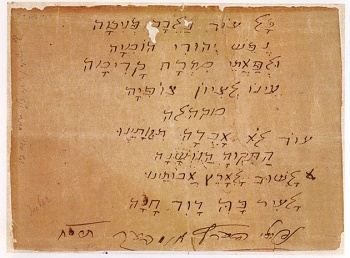

Here is the poem, Tikvatenu, as it originally appeared in Imber’s book:[5]

עוֹד לֹא אָבְדָה תִּקְוָתֵנוּ

הַתִּקְוָה הַנּוֹשָׁנָה

מִשּׁוּב לְאֶרֶץ אֲבוֹתֵינוּ

לְעִיר בָּהּ דָּוִד חָנָה.

I

Our hope is not yet lost,

The ancient hope,

To return to the land of our fathers;

The city where David encamped.

כָּל עוֹד בִּלְבָבוֹ שָׁם פְּנִימָה

נֶפֶשׁ יְהוּדִי הוֹמִיָּה

וּלְפַאֲתֵי מִזְרָח קָדִימָה

עֵינוֹ לְצִיּוֹן צוֹפִיָּה.

II

As long as in his heart within,

A soul of a Jew still yearns,

And onwards towards the ends of the east,

His eye still looks towards Zion.

כָּל עוֹד דְּמָעוֹת מֵעֵינֵינוּ

תֵּרֵדְנָה כְּגֶשֶׁם נְדָבוֹת

וּרְבָבוֹת מִבְּנֵי עַמֵּנוּ

עוֹד הוֹלְכִים לְקִבְרֵי־אָבוֹת.

III

As long as tears from our eyes

Flow like benevolent rain,

And throngs of our countrymen

Still pay homage at the graves of our fathers.

כָּל עוֹד חוֹמַת־מַחְמַדֵּינוּ

עוֹד לְעֵינֵינוּ מֵיפַעַת

וַעֲלֵי חֻרְבַּן מִקְדָּשֵׁנוּ

עַיִן אַחַת עוֹד דּוֹמַעַת.

IV

As long as our precious Wall

Appears before our eyes,

And over the destruction of our Temple

An eye still wells up with tears.

כָּל עוֹד הַיַּרְדֵּן בְּגָאוֹן

מְלֹא גְּדוֹתָיו יִזֹלוּ

וּלְיָם כִּנֶּרֶת בְּשָׁאוֹן

בְּקוֹל הֲמֻלָּה יִפֹּלוּן.

V

As long as the waters of the Jordan

In fullness swell its banks,

And down to the Sea of Galilee

With tumultuous noise fall.

כָּל עוֹד שָׁם עֲלֵי דְּרָכַיִם

שָׁם שַׁעַר יֻכַּת שְׁאִיָּה

וּבֵין חָרְבוֹת יְרוּשָׁלַיִם

עוֹד בַּת־צִיּוֹן בּוֹכִיָּה.

VI[6]

As long as on the barren highways

The humbled city-gates mark,

And among the ruins of Jerusalem

A daughter of Zion still cries.

כָּל עוֹד שָׁמָּה דְּמָעוֹת טְהוֹרוֹת

מֵעֵין־עַמִּי נוֹזְלוֹת

לִבְכּוֹת לְצִיּוֹן בְּרֹאש אַשְׁמוֹרוֹת

יָקוּם בַּחֲצִי הַלֵּילוֹת.

VII

As long as pure tears

Flow from the eye of a daughter of my nation

And to mourn for Zion at the watch of night

She still rises in the middle of the nights.

כָּל עוֹד רֶגֶשׁ אַהֲבַת־הַלְּאֹם

בְּלֵב הַיְּהוּדִי פּוֹעֵם

עוֹד נוּכַל קַוֵּה גַּם הַיּוֹם

כִּי יְרַחֲמֵנוּ אֵל זוֹעֵם.

VIII

As long as the feeling of love of nation

Throbs in the heart of a Jew,

We can still hope even today

That a wrathful God may have mercy on us.

שִׁמְעוּ אַחַי בְּאַרְצוֹת נוּדִי

אֶת קוֹל אַחַד חוֹזֵינוּ

"כִּי רַק עִם אַחֲרוֹן הַיְּהוּדִי

גַּם אַחֲרִית תִּקְוָתֵנוּ".

IX

Hear, oh my brothers in the lands of exile,

The voice of one of our visionaries,

[Who declares] that only with the very last Jew,

Only there is the end of our hope!

Hatikva has been uplifting hearts ever since it was written, toward the end of the 19th century, and has given voice to the 2,000-year-old hope, thanks to its stirring melody and the quasi-biblical language used by the poet.

Biblical Allusions in the Tikvatenu: A Look at the Song

The first stanza of the original Hatikva (the second stanza of today’s national anthem) contains two powerful biblical citations, but only one of them was retained in the final version.

Ezekiel’s Vision: The Valley of the Dry Bones

The first line of the first stanza reads: עוד לא אבדה תקותינו “Our hope is not yet lost,” expressing the persistent faith in the possibility of returning to the Jewish homeland. These words are based on Ezekiel’s vision of the dry bones:

יחזקאל לז:יא וַיֹּאמֶר֘ אֵלַי֒ בֶּן־אָדָ֕ם הָעֲצָמ֣וֹת הָאֵ֔לֶּה כָּל־בֵּ֥ית יִשְׂרָאֵ֖ל הֵ֑מָּה הִנֵּ֣ה אֹמְרִ֗ים יָבְשׁ֧וּ עַצְמוֹתֵ֛ינוּ וְאָבְדָ֥ה תִקְוָתֵ֖נוּ נִגְזַ֥רְנוּ לָֽנוּ:

Ezek 37:11 Then He said unto me: “Son of man, these bones are the whole house of Israel; behold, they say: ‘Our bones are dried up, and our hope is lost; we are clean cut off.’”

These words of despair are uttered by the dead, whom Ezekiel awakened, and into whose bones he breathed a renewed spirit. They represent Israel’s lack of faith even in the presence of the great miracle they have experienced – their own resurrection. Imber turns these words on their head: “Our hope is not yet lost.” In other words, contrary to the biblical statement, we have not yet been redeemed or been revived, yet our hope is not lost.[7] Thus, he proffers a reference to the biblical text but turns the words of defeat into words of courageous hope.

The City Where David Encamped: Removing a Messianic Insinuation

The second prominent biblical citation in the original version of the poem was not retained in the official version of Hatikva we sing today. The revision of this line was proposed by Dr. Yehuda Leib Matmon-Cohen (years later the founder of the Tel Aviv Gymnasia school) in or around 1905:

Revised (Matmon-Cohen)

עוֹד לֹא אָבְדָה תִּקְוָתֵנוּ

הַתִּקְוָה בַּת שְׁנוֹת אַלְפַּיִם

לִהְיוֹת עַם חָפְשִׁי בְּאַרְצֵנוּ

אֶרֶץ צִיּוֹן וִירוּשָׁלַיִם.

Our hope is not yet lost,

The hope that is two thousand years old,

To be a free nation in our land,

The Land of Zion, Jerusalem

Original (Imber)

עוֹד לֹא אָבְדָה תִּקְוָתֵנוּ

הַתִּקְוָה הַנּוֹשָׁנָה

מִשּׁוּב לְאֶרֶץ אֲבוֹתֵינוּ

לְעִיר בָּהּ דָּוִד חָנָה.

Our hope is not yet lost,

The ancient hope,

To return to the land of our fathers;

The city where David encamped.

The original version written by Imber is based on Isaiah 29:1:

תהלים כט:א ה֚וֹי אֲרִיאֵ֣ל אֲרִיאֵ֔ל קִרְיַ֖ת חָנָ֣ה דָוִ֑ד

Isa 29:1 Ah, Ariel, Ariel, the city where David encamped.

This verse is excerpted from Isaiah’s prophecy of rebuke against the people of Jerusalem, and he laments what will become of the city. The phrase “city where David encamped” refers to Jerusalem, as it was King David who established the city as Israel’s capital.

Matmon-Cohen suggested the revision, which retains the expression of longing for Zion, but removes the messianic insinuation, as the original poem creates an affinity between the generations-long yearnings of the Jews and King David, who according to Jewish tradition is the forebear of the Messiah.

This revision, like the deletion of the stanzas depicting the weeping over the destruction, the prostration over the forefathers’ graves, and citations from the biblical chapters on the destruction, paved the way for Hatikva to become the national anthem for the Zionist movement, which was comprised mostly secular Jews. This revision altered the messianic nature of the poem to that of a nation yearning for its homeland.

Biblical References in the Remaining Stanzas of the Poem

Tikvatenu contains additional biblical citations, let us explore a few of them.[8]

A Bountiful Rain

The third of the original nine stanzas states:

כָּל עוֹד דְּמָעוֹת מֵעֵינֵינוּ

תֵּרֵדְנָה כְּגֶשֶׁם נְדָבוֹת

וּרְבָבוֹת מִבְּנֵי עַמֵּנוּ

עוֹד הוֹלְכִים לְקִבְרֵי אָבוֹת.

As long as tears from our eyes

Flow like benevolent rain,

And throngs of our countrymen

Still pay homage at the graves of our fathers.

The expression “benevolent rain,” comes from Psalms 68:10:

תהלים סח:י גֶּ֣שֶׁם נְ֭דָבוֹת תָּנִ֣יף אֱלֹהִ֑ים

נַחֲלָתְךָ֥ וְ֝נִלְאָ֗ה אַתָּ֥ה כֽוֹנַנְתָּֽהּ:

Ps 68:10 You released a benevolent rain, O God;

When Your own land languished, You sustained it.

The emotional pathos in this poem is typical of Imber’s generation – to him tears are “benevolent rain.” Chaim Nachman Bialik, who represents the next (and more contained) generation of Hebrew poets, reduced them to, “that single boiling tear (דמעה הרותחת ההיא)” in his 1902 poem Levadi (“Alone”), which reflects a different poetic aesthetic than that of poets of Imber’s generation.

Controversial Reference to God

The mention of God in the original poem also posed a problem for those who wanted Hatikva to be the national anthem. For example, the eighth stanza contains an allusion to Psalms 7:12:

Tikvatenu

כִּי יְרַחֲמֵנוּ אֵל זוֹעֵם.

That a wrathful God may still have mercy on us.

Psalms

תהלים ז:יב אֱ֭לֹהִים שׁוֹפֵ֣ט צַדִּ֑יק

וְ֝אֵ֗ל זֹעֵ֥ם בְּכָל־יֽוֹם:

Ps 7:12 God vindicates the righteous;

God pronounces wrath each day.

This was excluded—indeed, Hatikva contains no references to God!

References to Lamentations and the Destruction of the Temple

Many of the original biblical citations are excerpts from the prophecies of destruction and the Book of Lamentations. The line from stanza 4,

עַיִן אַחַת עוֹד דּוֹמַעַת

An eye still wells up with tears,

for example, picks up on the following verses:

ירמיה יג:יז וְדָמֹ֨עַ תִּדְמַ֜ע וְתֵרַ֤ד עֵינִי֙ דִּמְעָ֔ה

Jer 13:17 My eye must stream and flow with copious tears.

איכה א:ב וְדִמְעָתָהּ֙ עַ֣ל לֶֽחֱיָ֔הּ

Lam 1:2 Her tears are on her cheeks.

איכה א:טז עֵינִ֤י׀ עֵינִי֙ יֹ֣רְדָה מַּ֔יִם

Lam 1:16 My eyes run down with water.

The Original Ending

The original poem ended with a grandiloquent exclamation:

כִּי רַק עִם אַחֲרוֹן הַיְּהוּדִי

גַּם אַחֲרִית תִּקְוָתֵנוּ!

Only with the very last Jew,

Only there is the end of our hope!

This expression is embodied in the verse from Jeremiah:

ירמיה כט:יא כִּי֩ אָנֹכִ֨י יָדַ֜עְתִּי אֶת־הַמַּחֲשָׁבֹ֗ת אֲשֶׁ֧ר אָנֹכִ֛י חֹשֵׁ֥ב עֲלֵיכֶ֖ם נְאֻם־יְ־הוָה מַחְשְׁב֤וֹת שָׁלוֹם֙ וְלֹ֣א לְרָעָ֔ה לָתֵ֥ת לָכֶ֖ם אַחֲרִ֥ית וְתִקְוָֽה:

Jer 29:11 For I know the thoughts that I think towards you, says the Eternal, thoughts of peace and not of evil, to give you a future and a hope.

The prophet’s words of comfort seem to be interwoven in the poet’s proclamation of faith. Here too, Imber cited this verse in a creative fashion, as the message in the poem is that only the total annihilation of the Jewish People can extinguish the hope, while Jeremiah’s prophecy “a future and a hope” is a positive expression of dreams of redemption facilitated by God. Here too the strong religious overtones of the allusion may be responsible for the omission of the stanza.

Hatikva: A Dearth of Biblical References

As noted above, many of the biblical allusions in the original poem were abridged and revised out of existence, perhaps due to a desire to secularize the national anthem. Some biblical references remain in the official version, for example, the poem ends with:

אֶרֶץ צִיּוֹן וִיְרוּשָׁלַיִם

The Land of Zion, Jerusalem

This follows the biblical model, where Zion and Jerusalem appear as synonymous parallels.[9]

Wording similar to that of the anthem is found in several places in the Prophets, such as (Isaiah 24:23):

ישעיה כד:כג כִּֽי־מָלַ֞ךְ יְ־הוָה צְבָא֗וֹת בְּהַ֤ר צִיּוֹן֙ וּבִיר֣וּשָׁלִַ֔ם…

Isa 24:23 …for Eternal of hosts will reign in Mt. Zion and in Jerusalem…[10]

Yet the poem downplays the prophetic religious and messianic message, and Mt. Zion in the verse – the site of the Temple – becomes the country of the Zionists, the lovers of Zion.

A Biblical Hebrew Song Before the Rise of Modern Hebrew

The poem was published in 1886 (and apparently written about ten years previously), at the time of the beginning of the Hebrew language revival movement. Before this revival, modern Hebrew literature and poetry were indeed written and read, but spoken Hebrew was not widely used for everyday communication. The Safa Berura (Clear Language) Society, whose aim was to promote the speaking of Hebrew in Eretz Yisrael, and to help connect Ashkenazic and Sephardic Jews via the Hebrew language, was not founded until 1889.[11]

Thus, Imber wrote his poems in a period when Hebrew had not yet begun to function as an everyday language. Still, they are written in clear, natural language. The Hebrew comes to life in the lines that emanated from his heart, and seems neither artificial nor forced.[12]

A large percentage of the vocabulary in Tikvatenu (and, consequently, Hatikva) is biblical: words and expressions such as הומיה (yearns), צופיה (gazes), נושנה (ancient), לפאתי (towards the far corners), קדימה (onward), בת ציון (Daughter of Zion), יכת שאיה (destroyed) and more, represent the biblical register and lexicon. Thus, in addition to citing and reworking expressions from biblical verses, Imber’s choice of words and the style of this poem (although not to same extent in its syntax) create an air of biblical vitality.

Marking the Jewish Struggle

The singing of Hatikva has accompanied landmarks along the path of Jewish history ever since this poem was written. It was sung with great vigor in the moshavot of the First Aliyah at the Zionist congresses in the early years of the 20th century, and is sung on every momentous national occasion to this day.

An emotional recording by the BBC in 1945 immortalizes the voices of hundreds of survivors of Begen-Belsen concentration camp, singing Hatikva during a special Kabbalat Shabbat service in the camp just five days after their liberation. The inner strength and power of the liberated concentration camp inmates is evident in the recording. Three years later, Hatikva was sung following the proclamation of the establishment of the State of Israel, on 5 Iyar, 5708 (May 14, 1948) at the Tel Aviv Museum, and afterward it was played by the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra.

Even though Hatikva was firmly established in the public’s consciousness as Israel’s national anthem, it was not formally legislated as such until 57 years after the establishment of the state, in a 2004 amendment to the Flag and Emblem Law, which was changed to the Flag, Emblem and National Anthem Law.

A Modern Prayer or Kapitel (Chapter of) Tehilim

Hatikva is not a prayer in the accepted sense of the word, and certainly not in the formal version that serves as Israel’s national anthem. It does not appeal to God, but does relate to the lofty, eternal and spiritual, and is therefore considered a prayer by some Jews. Hatikva has been played in a wide variety of musical arrangements and has been recruited for both political and liturgical purposes.

In many synagogues, it is customary to sing Hatikva at the conclusion of the Yom Kippur service, and many cantors or prayer leaders (שליחי ציבור) sing various prayers to the tune of Hatikva, during the Mussaf service on Rosh Hashanah, for example, at the end of Ne’ilah or at the end of the Pesach Haggadah.

Albeit with objections from different segments of the Israeli society,[13] for over 130 years, Hatikva has served as a modern psalm for the Jewish People. Its various, though selected, types of uses of biblical material have helped cement its relationship with the Jewish community, and have made it sound like a quasi-biblical, though modern, psalm, which connects Hatikva to Jewish tradition in a profound manner.

This connection has made Hatikva canonical, not only officially, but as an integral and powerful part of Israeli culture. Over the years, this poem, which quotes from the Bible, itself became a wellspring for citation – for a plethora of songs, slogans, posters and expressions quoting directly or indirectly from the national anthem.

The para-liturgical nature of Imber’s poem can be demonstrated in a line from Nathan Alterman’s poem, Himnon U’mehavro (An anthem and its author). Alterman wrote his poem in 1953, when Imber’s remains were brought to Jerusalem to be buried. It asks:

מִי כַשִׁיר הַזֶּה עַל פִּי הָעָם שָׁגוּר?

שֶׁמָא רַק תְפִלוֹת מִסְפָּר שֶׁבַּסִּדּוּר.

Which poem is so well-known by the people?

Perhaps only a handful prayers in the siddur.[14]

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

May 10, 2016

|

Last Updated

April 11, 2024

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Footnotes

Prof. Rabbi Dalia Marx is Professor of Liturgy and Midrash at Hebrew Union College-JIR (Jerusalem). She earned her Ph.D. at the Hebrew University and her rabbinic ordination at HUC-JIR (Jerusalem and Cincinnati). Among her publications are When I Sleep and When I Wake: On Prayers between Dusk and Dawn and A Feminist Commentary of the Babylonian Talmud. Her website is: www.dalia-marx.com.

Essays on Related Topics: