Edit article

Edit articleSeries

Symposium

What We Know About Slavery in Egypt

Slave brick-makers, depicted in the tomb of the vizier Rekmire, c. 1450 BCE.

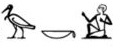

While the Egyptians used several terms to convey the notion of forced labor,[1] Egyptologists have typically used the translation “slave, servant” to understand two Egyptian terms:

- Slave/Servant: Hm/Hmt (masculine:

; feminine:

; feminine: ).

). - Servant/ Worker: bAk/bAkt (masculine:

; feminine:

; feminine: ).

).

The latter is also often translated as “worker.”[2] It is possible that the status intended by the use of the word Hm was restricted to foreigners, as Egyptians who gave up their legal freedoms (due to famine, debt, etc.) were referred to as bAk.w not Hm.w.[3]

Due to the absence of law codes from ancient Egypt, the legal status of slaves was never fully explained. Nevertheless, the following sample of Egyptian texts dealing with slavery from the Middle Kingdom through the New Kingdom offers insight into the complex relationship between various dependent workers, slaves, and Egyptian elites.

Middle Kingdom (2000-1700 B.C.E.) and 2nd Intermediate Period (1700-1550 B.C.E.)

One famous Middle Kingdom text, the “Satire of the Trades,”[4] outlines the dangers and misfortunes that accompany seemingly every occupation but that of the scribe. Noticeably absent is the role of slavery, which one prominent Egyptologist reasonably believes was not a clearly defined social group during this time.[5] Various phrases referring to a type of forced labor are, however, found in the Satire:

- w Hr bAk.f (“drawn/made to work”),

- w Hr bAk.f mni.ti (“made to work in the fields”),

- tw.f m Ssm 50 (“beaten with 50 lashes” for a day’s absence), etc.

The concept of forced labor is clear in this text, yet it doesn't explicitly mention slavery. This is emblematic of the problems of terminology.

In another Middle Kingdom text, the Westcar Papyrus, the term Hm is used to describe two individuals massaging their master, the legendary magician Dedi:

It was lying down on a mat at the threshold of his house that he found him (Dedi), a slave (Hm) at his head massaging him and another wiping his feet.[6]

Various documents during this period mention for the first time commercial transactions involving workers (bAk.w). One text mentions the purchase of three male workers and seven female ones to add to those inherited by his father, while another individual added twenty “heads,” namely slaves or servants to his estate.[7] That they were purchased and added to an inheritance seems to indicate a form of long-term servitude or slavery, but again the terms are ambiguous, especially “heads.”

Captured Foreigners

More obvious is the case of specific Asiatics, who were captured in military campaigns, reduced to slavery, and then entrusted to individuals as property, who could then be inherited or sold.[8]

Taken as a whole, both native-born Egyptians and foreigners could thus serve as slaves/servants. Antonio Loprieno notes,

[O]f the seventy-nine servants presented in the list on the verso side of the Brooklyn Papyrus as belonging to a single owner, at least thirty-three were Egyptians![9]

Again, it must be stressed that there is no consensus as to the precise legal statuses of those called “slaves/servants” (Hm.w) or “workers” (bAk.w).

Other Terms Relevant to Slavery

Other terms Middle Kingdom terminology also includes the following:

- Conscripts (w) – Those who were conscripted to serve in the army, labor in building or agricultural projects or mining quarries as a temporary labor force.

- Deserters (w) – The punishment for desertion was a life of labor.[10]

- Royal servants (w-nzw) – Egyptians who shared the status of the Asiatic slaves, and, in contrast to conscripted workers, if they fled they were executed.[11]

Unique cases of interaction between slaves and masters are evident in this time period. A slave named Uadjhau was taught to read and write by his master.[12] During the Second Intermediate Period, if not earlier, it was possible to earn freedom and citizenship through marriage.[13]

New Kingdom (1550-1070 B.C.E.)

During the New Kingdom, most slaves were foreigners, who replaced the roles previously held by royal servants and conscripts.[14] Many were prisoners of war, but there is evidence of slave trade as well. Amenhotep III wrote to Milkilu of Gezer that he was sending an official to trade various goods for “beautiful cupbearers without blemish.”[15]

Slave Work

Slaves plowed fields, planted and harvested crops, tended cattle, and worked with textiles in service to temple estates. They could also serve as butlers, beer-makers, fan-bearers, shield-bearers, and mercenaries.[16] An Egyptian official, Setau, used foreign slaves to construct and work at the temple at the Wadi es-Sebua.[17] Slaves were also brick-makers, as depicted in a famous scene from the tomb of the vizier Rekmire (ca. 1450 B.C.E.) and in a leather scroll now housed in the Louvre dating to Ramesses II.[18]

At the workmen’s village of Deir el Medina, the state provided slaves for individual households; these slaves were paid in grain rations and may even have been rented out to others, allowing the original owner to earn additional income from their labor.[19] Prisoners were given as rewards to individuals, as noted several times in the texts of the soldiers Ahmose son of Ibana and Amenemheb and the treasurer Maia.[20]

Emancipation of Slaves

Foreign slaves in the New Kingdom could be emancipated in several different ways. A slave named, Ameniu was awarded his freedom in exchange for marrying his owner’s invalid niece.[21] Slaves could also be freed through adoption, as was the case for the children of the slave girl Dienihatiri, whose owner adopted her children. One of the girls, Taimennut, married the overseer of the stables, Pendiu. Any children born to them were free citizens.[22]

Another path to freedom was to be purified (swab) by the king himself, as noted in Tutankhamen’s Restoration Stele. Slaves could earn taxable wages, had some judicial rights, could marry and start families, and even keep their original names.[23]

Overall, slaves played many roles in New Kingdom Egypt, a highly complex society that came to increasingly rely on slave labor for its economic prosperity.[24]

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

April 18, 2016

|

Last Updated

February 10, 2026

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Dr. Mark Janzen is assistant professor of history and archaeology at Southwestern Baptist Theologocial Seminary. He holds a Ph.D. in history/Egyptology from the University of Memphis, and an M.A. in Biblical and Near Eastern Archaeology from Trinity Evangelical Divinity School. His dissertation is titled, “The Iconography of Humiliation: The Depiction and Treatment of Foreign Captives in New Kingdom Egypt.”

Essays on Related Topics: