Edit article

Edit articleSeries

The Significance of Hittite Treaties for Biblical Studies and Orthodox Judaism

Hattusa the capital of the Hittite Empire in the late Bronze Age. Wikimedia

Biblical scholars refuse to let the Hittites, residents of the once powerful kingdom in ancient Turkey, rest in peace. Despite their extinction as a civilization three-thousand years ago, the Hittites continue to make headlines. (If you haven’t noticed, you’re obviously reading the wrong blogs.) In a series of insightful and provocative essays dealing with the relationship between academic biblical study and Orthodoxy, which appeared on Torah Musings, my colleague Professor Joshua Berman has shown how the late second millennium BCE Hittite vassal treaties can deepen our understanding of the biblical notion of covenant (ברית). Moreover, he argues for the possibility that these ancient documents can be used to prove the antiquity and coherence of the Torah.[1]

Background

The history of modern research into the biblical covenant is one of polemics.[2] At the turn of the twentieth century (CE), academic scholarship was divided about the antiquity of the concept of “covenant” in the Bible. Julius Wellhausen and others claimed that the covenant was unknown before the exilic period. More sociological and anthropologically inclined scholars such as Max Weber and William Robertson Smith, on the other hand, viewed the notion of covenant as central to the early formation of Israel.[3] The latter tendency gradually became dominant when George Mendenhall emerged on the scene with a secret weapon that eradicated the opposition – the Hittite vassal treaties.[4]

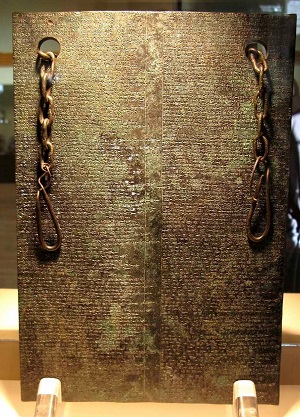

Building on the ground-breaking analysis of the historian of law Victor Korošec, Mendenhall used the similarities between the Hittite treaties and covenantal passages in the Bible as empirical evidence for the antiquity of the latter. Particular attention was given to the structure of the Hittite treaties, which featured the following sections (even though not all are present in any given document):

Building on the ground-breaking analysis of the historian of law Victor Korošec, Mendenhall used the similarities between the Hittite treaties and covenantal passages in the Bible as empirical evidence for the antiquity of the latter. Particular attention was given to the structure of the Hittite treaties, which featured the following sections (even though not all are present in any given document):

- Historical prologue

- Presentation of the parties to the treaty

- Conditions of the treaty

- Witnesses (list of various gods)

- Blessings and curses

In comparison with treaty forms found in other parts of the Near East, the inclusion of a historical prologue and blessings alongside the curses can be viewed as distinctive. Strikingly, several covenantal texts in the Bible also feature these two sections, especially the Book of Deuteronomy – taken in its entirety as a treaty form – and Joshua 24. On the other hand, these two sections are absent from the Neo-Assyrian treaties, from the eighth and seventh centuries, which others believe were the main influence on Deuteronomy. These observations served as the basis for Mendenhall’s argument that the biblical sources reflect a late 2nd millennium BCE date of composition, not the much later dates that were accepted by most biblical scholars.

Moreover, the presence of these two sections – a historical introduction recollecting the loyalty of the two parties in the past and the set of blessings rewarding loyalty to the contract – should be viewed as an expression of the fundamental difference in approach between the Hittite and Neo-Assyrian treaties. Whereas the Neo-Assyrian treaties employ fear as the singular basis for compelling the loyalty of the vassal, the Hittite treaties are based on the principal of reciprocity, which emphasizes the mutual benefits offered to both sides. This latter approach finds analogues in the Bible that tends to temper any coercive aspects of the covenant by emphasizing the positive aspects of the relationship.

Despite these similarities, more recent scholarship has tended to find traces of Neo-Assyrian influence in Deuteronomy. Specifically, close linguistic parallels between Deuteronomy and Esarhaddon’s Succession Treaty (7th cent. BCE)[5]supported the classical view that the scroll discovered by King Josiah in 2 Kings 22– 23 was none other than the book of Deuteronomy (which was not written long before then).[6]Berman challenges this consensus in his renewed examination of the Hittite treaties, ultimately supporting Mendenhall’s earlier dating of Deuteronomy.

Deuteronomy 1-3 and the Hittite Historical Prologue

Close study of the opening section of Deuteronomy leads into another problem, no less serious from a traditional Jewish perspective than the dating of the text, namely the internal tensions within the Bible. Specifically, the numerous contradictions between the historical description in the opening of Deuteronomy and that of Exodus-Numbers would seem to cast doubt on the singular authorship of these books.[7]

Recognizing these contradictions, Berman has turned again to the Hittite vassal treaties – and found a novel solution. Building on earlier research on these treaties,[8] Berman refers to the existence of ostensibly contradictory historical accounts, for example, the variant accounts of the submission of Aziru, ruler of Amurru. Without going into detail here, Berman suggests that the rewriting of history in these treaties was taken as “diplomatic signaling,” through which the relations between the suzerain and vassal were redefined. In this manner, the largely more critical account of the wilderness in Deuteronomy was not intended to erase the previous history of the wilderness wanderings, but rather to reframe them with the aim of rebuking the Israelites in the plains of Moab.[9]

This provocative suggestion deserves careful consideration, but here I will just add a few brief observations. First, several scholars in the field of Hittitology have offered interpretations which preserve the essential historicity of these treaties, such that they may not necessarily provide the external evidence that Berman seeks.[10] Be that as it may, I believe that Berman’s approach to the biblical evidence should be evaluated on its own merit, providing a compelling understanding of how Deuteronomy 1–3 can be read together with the previous books of the Torah. However, once one accepts in principal that the author of Deuteronomy is rewriting history – subordinating historical accuracy to its deeper moral and religious message, we may wonder if this approach may not encourage a less literalistic understanding of Mosaic authorship.[11]

Problems with Using the Hittite Material to Support Early Dating

Returning to the touchy topic of the dating of Deuteronomy in modern scholarship, there are several problems in using the Hittite treaties to establish an early dating for Deuteronomy. First of all, it may be possible to account for the general similarities – the notions of benevolence and reciprocity – found in the Hittite treaties and the biblical covenant as stemming from more basic socio-political similarities between the two cultures, such that these need not be attributable to specific historical influence.

Indeed, in his book Admonition and Curse, the most comprehensive recent treatment of the treaty and covenant traditions in the ancient Near East, the author, Noel Weeks, abandons the once-dominant attempt to link a particular treaty form with a specific historical period.[12] In his provocatively-titled final chapter “The Significance Of It All,” the reader is disappointed to discover the author’s sober and rather unsensational conclusion: The treaty form is a common inheritance of the ancient Near East which took distinct forms in local traditions, concluding that even if “some of these local traditions have tantalizing similarities… similarity may have diverse causes” (182).

Berman attempts to overcome these objections by demonstrating striking structural and linguistic parallels between a specific Hittite treaty and Deuteronomy 13.[13] This Hittite treaty is with a group of people from an area called Kizzuwatna, located in southernmost Anatolia (Turkey), hence originating from a geographic area relatively close to Canaan. These similarities would potentially demonstrate a much clearer case of influence. However, it is doubtful that these parallels will change the consensus in biblical scholarship, since linguistic and structural parallels have also been found connecting the Neo-Assyrian treaties of Esarhaddon (7th cent.) with Deuteronomy, including Chapter 13 and the treaty-curses of Chapter 28.[14] These are as close, if not closer, than the parallels found in the Hittite treaties.

Concluding Reflection

My purpose here is not to settle these issues; clearly, any resolution between academic scholarship and Orthodoxy will not be easy to come by. A person who derives his or her “permission to believe” from empirical evidence will need to evaluate the evidence. A religious claim that can be verified by scientific inquiry today can be falsified by it tomorrow.

Let me suggest, however, that it may be the very notion of covenant that can resolve the tension between rationality and religion (emunah). As demonstrated by Berman and earlier scholars, an understanding of the treaty traditions provides essential background for comprehending how the Israelite relationship with God was modeled metaphorically on the relations between king and vassal, in Deuteronomy and many other biblical books.[15]

Despite occasional claims to the contrary, Israel’s self-understanding as a people in a covenantal relation with God was unique in the ancient Near East and served as a central pillar of biblical religion. Moreover, in the face of national catastrophes – the destructions of Samaria and Jerusalem – it enabled the Israelites and Judahites to overcome the cognitive dissonance between their faith and the bitter reality, allowing them to interpret the events as a divine punishment. This same sense of covenant enabled Israel to survive as a persecuted minority in exile.

Just as this steadfast conception has provided the Jewish people with the flexibility to survive in the most unhospitable conditions of national existence, I believe that the covenant offers a viable framework for maintaining an unbreakable commitment to Torah as part of a rationalistic and rigorously critical approach to reality. That is, in my view, the significance of it all.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

March 4, 2014

|

Last Updated

April 12, 2024

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Footnotes

Dr. Yitzhaq Feder is a lecturer at the University of Haifa. He is the author of Blood Expiation in Hittite and Biblical Ritual: Origins, Context and Meaning (Society of Biblical Literature, 2011). His most recent book, Purity and Pollution in the Hebrew Bible: From Embodied Experience to Moral Metaphor (Cambridge University Press, 2021), examines the psychological foundations of impurity in ancient Israel.

Essays on Related Topics: