Edit article

Edit articleSeries

Ezekiel: A Jewish Priest and a Babylonian Intellectual

Ezekiel, close-up of the southern portal of the facade of the cathedral Notre-Dame in Amiens, France. Credit Guillaume Piolle / Wikimedia

The pyrotechnics of Ezekiel’s first vision (Ezek 1:4) are comparable to and perhaps even surpass the spectacle of sound and light that accompanied the revelation of Torah at Sinai (Exodus 19:16, 18).[3] The prophet, or those who committed his words to writing,[4] demonstrated unparalleled mastery of literary style, imagery, and metaphor, features that contribute to the perception that the book presents some of the “most theologically challenging and dynamic material among the prophets of the Bible, and some of the most difficult and bizarre passages.”[5]

However, it is not the medium of Ezekiel’s message, or even the message itself, that is the focus here. Rather, the seemingly inconsequential location at which the divine word was made manifest to the prophet serves as a jumping-off point for this essay, which aims to locate the prophet Ezekiel in the social, economic, and intellectual contexts of the communities of Judean exiles in sixth-fifth century BCE Mesopotamia.

The Rivers of Babylon

In Mesopotamia, the land between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, the waters of Babylon, —both the springtime floods and the controlled flow coursing through canals and irrigation ditches — sustained great empires of the ancient world, the fabled kingdoms of Nebuchadnezzar, Cyrus, Darius, and Xerxes.

The sweet waters which supported agriculture and urban life also absorbed the bitter tears of exiled Judeans as they sang, prompted by their captors, of their homeland (Psalm 137:1-2):

עַל נַהֲרוֹת בָּבֶל שָׁם יָשַׁבְנוּ גַּם בָּכִינוּ בְּזָכְרֵנוּ אֶת צִיּוֹן. עַל עֲרָבִים בְּתוֹכָהּ תָּלִינוּ כִּנֹּרוֹתֵינוּ.

By the rivers of Babylon, there we sat down, yea, we wept when we remembered Zion. Upon the willows in the midst thereof, we hanged up our harps.

One of those waterways in particular, the river Chebar was the locus at which Ezekiel’s mission began; it is named in the opening line of the haftarah read on Shavuot (Ezek 1:1):

וַיְהִי בִּשְׁלֹשִׁים שָׁנָה בָּרְבִיעִי בַּחֲמִשָּׁה לַחֹדֶשׁ וַאֲנִי בְתוֹךְ הַגּוֹלָה עַל נְהַר כְּבָר נִפְתְּחוּ הַשָּׁמַיִם וָאֶרְאֶה מַרְאוֹת אֱלֹהִים.

Now it came to pass in the thirtieth year, in the fourth month, in the fifth day of the month, as I was among the captives by the river Chebar, that the heavens were opened, and I saw visions of God.

These lines situate the prophet’s call early in the captivity of Jehoiachin, the Judahite king exiled to Babylon at eighteen years of age[6]; they identify the prophet as a priest and son of Buzi, and note that the hand of the Lord was upon Ezekiel by the river Chebar.[7]

The Chebar Canal

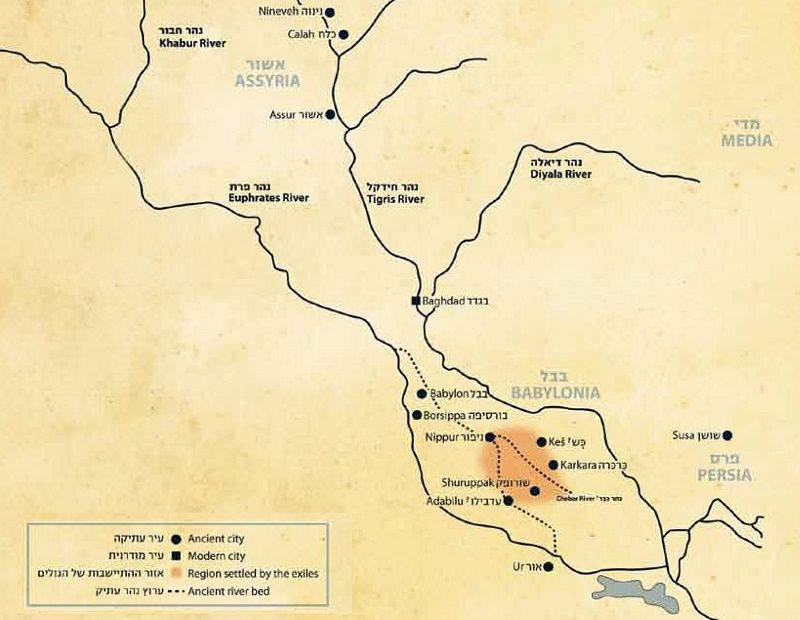

The Chebar canal is the Nār Kabari that appears in legal and administrative cuneiform texts of the “long sixth century” (626-477 BCE).[8] Its course can no longer be traced with certainty, yet it is generally agreed that it flowed from the area around Babylon eastward toward Susa, connecting small settlements and major towns in the Mesopotamian countryside indirectly to the Achaemenid capital cities of Babylon and Susa.[9]

The waterway’s role as a commercial route is not in doubt,[10] and as members of native and deportee populations traveled along it, they shared and transmitted Mesopotamian intellectual and cultural achievements.

The Babylonian Resettlement Strategy

In the wake of Nebuchadnezzar’s military conquests in the Levant, Judeans and other population groups were relocated to the south-eastern reaches of the Mesopotamian heartland in settlements that were named for their places of origin.[11]Such towns, sometimes referred to a “mirror towns,”[12] reflect and preserve the geographic and cultural background of their inhabitants.

Maintaining intact a critical mass of each of the diverse population groups was a means of supporting the primary economic objective of the resettlement agenda, namely, the revitalization of lands devastated in the Assyro-Babylonian wars at the end of the 7th century BCE that contributed to the downfall of the Assyrian empire. Peoples of similar geographic, linguistic, and even religious backgrounds might be expected to more readily and productively collaborate in working together in a new environment.[13]

The Murašû Texts and (āl-)Yāḫūdu, “Judah(town)”

Judean exiles are now attested in cuneiform documentation composed in settlements proximate to the Nār Kabari. The first evidence recovered in modern times documenting the presence of Judeans in the Babylonian landscape was the archive of the Murašû family. In these texts, excavated at Nippur, Judeans primarily appeared as witnesses to documents recording transactions typical of the land-for-service economic sector. The Murašû texts date from 454-400 BCE, approximately 130 years following the destruction of the First Temple.

Later, nearly fifty cuneiform texts written in a settlement called (āl-)Yāḫūdu, “Judah(town)”[14] were published. These texts document the presence of Judeans on the Mesopotamian landscape from 572-474 BCE (year 32 of Nebuchadnezzar to year 9 of Xerxes), only twenty-five years following the first wave of deportations or nearly fifteen years after the destruction of the Jerusalem Temple.[15] Although the precise location of āl-Yāḫūdu is not known, internal evidence in the texts shows that it, and nearby towns in which other West Semitic deportees resided, lay in a triangle that expanded eastward from Nippur.

Thus, the (āl-)Yāḫūdu texts, the earliest of which dates to 572 BCE, have contributed the evidence for a nearly continuous Judean presence in southern Babylonia from the start of the Exile through the period of Achaemenid (early Persian) rule. Texts from Susa and Sippar document Judeans participating in other social and economic sectors, as court officials and royal merchants, respectively.[16]

Ezekiel: An Intellectual Prophet

Although he prophesied at the Chebar waterway that ran through the agricultural lands of southern Mesopotamia, nothing in his book confirms Ezekiel’s likely participation in the agricultural sector of the economy from which the majority of cuneiform documentation of Judeans in Babylonia derives. Rather, Ezekiel the prophet, an intellectual in the eyes of many, was responsible for the biblical book marked by the densest concentration of evidence of cross-cultural contact and influence; the number of loanwords and literary motifs rooted in the Babylonian language is staggering.[17]

Ezekiel prophesies in Babylon, but in some of his visions, he is transported back to Jerusalem (e.g., Ezek 8:3, 40:1-2). David Vanderhooft observes that Ezekiel was the only prophet to experience “visionary transportation between the two acculturative loces — Babylonia and Jerusalem”[18] and describes Ezekiel as “a kind of intellectual interlocutor who deciphers the experience of Babylon for his Judean compatriots.”[19]

Ezekiel’s brilliance lies in his mastery of the Babylonian realia—for example, transforming specialized vocabulary such as Akkadian elmešu-stone into ḥašmal (Ezek 1:26-27) — and modes of thought—such as aspects of the organization of the heavens—and his integration of them into the divine message with which he is charged, a message intended to confront the exiled Judeans for their abandonment of God.[20]

The challenge remains to determine how, in view of his having been brought to Babylon as an adult, Ezekiel acquired his knowledge of Babylonian intellectual culture. A number of suggestions follow.

1. Part of the Babylonian Elite

Following a demonstration of the linguistic and epigraphic fluidity and complexity of Babylonian hermeneutical techniques employed in the first millennium BCE, British Assyriologist Irving Finkel bravely suggests a scenario in which “the best brains among the Judeans were taught cuneiform by the best teachers in the country” accounts for the reflexes of these methods in Jewish scholarship.[21]

Composition of the Babylonian Elite

The exposure of Judeans to Babylonian intellectual process undoubtedly occurred over time. Nevertheless, the on-going production of cuneiform culture (that continued even into the Hellenistic period) generally reflects the activity of members of the close-knit and socially closed world of the Babylonian urban elite.[22] This group included, in addition to the Babylonian literati and intelligentsia — scientists, astronomers, priests — individuals who, in contemporary parlance, might be termed members of upper middle class professions — judges, merchants, etc.

Elite Babylonians traced their lineage through a small number of families or clans, and consistently included that affiliation when providing their names, for example, a scribe active in the area of (āl-)Yāḫūdu was named Arad-Gula, son of Nabû-šum-ukīn, descendant of Amēl-Ea.[23] Minorities, including Judeans and members of other deportee populations, are not attested as cuneiform scribes, even in the most mundane administrative documents. Thus, another, non-hereditary means that could account for an early acceptance of (presumably educated and erudite) Judeans into elite Babylonian intellectual circles should be sought.

2. The Curricular Context

Jonathan Stökl suggests the individuals such as Ezekiel were exposed to the lower levels of the Babylonian curriculum as one institutionalized context in which linguistic contact occurred in the multilingual environment that obtained around the time of Ezekiel’s writings.[24] Certainly, the notion that some Judeans received cuneiform scribal training is suggested by Daniel 1:3-4:

וַיֹּאמֶר הַמֶּלֶךְ לְאַשְׁפְּנַז רַב סָרִיסָיו לְהָבִיא מִבְּנֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל וּמִזֶּרַע הַמְּלוּכָה וּמִן הַפַּרְתְּמִים… וַאֲשֶׁר כֹּחַ בָּהֶם לַעֲמֹד בְּהֵיכַל הַמֶּלֶךְ וּלֲלַמְּדָם סֵפֶר וּלְשׁוֹן כַּשְׂדִּים.

And the king spoke unto Ash-penaz his chief officer, that he should bring in certain of the children of Israel, and of the seed royal, and of the nobles,[25] … such as had ability to stand in the king’s palace; and that he should teach them in the learning and the tongue of the Chaldeans.

Judeans (or other non-native residents of Babylonia) who attended the cuneiform academy would have followed the traditional Babylonian curriculum.

The Babylonian Curriculum

The history of the Babylonian cuneiform scribal school is long, its fully developed curriculum enduring, with some modification, from the Old Babylonian (roughly 1800-1600 BCE) through the Neo-Babylonian (626-539 BCE) periods and beyond.[26] Thus, to a large extent the curriculum in use at the time of the composition or redaction of Ezekiel’s prophecies resembled that established more than a millennium earlier. It was a vehicle for training that supported increasingly complex levels of literacy: functional, technical, and scholarly.[27]

Mastery of the basic curriculum could be achieved in three years, of the secondary stage in again three; advanced study might follow.[28] Primary education included study of vocabulary lists, including one that was a Sumerian-Akkadian compendium of terms primarily in use in commercial endeavors that scholars refer to as “ur5-ra = ḫubullu” (“debt, interest-bearing loan”) based on its first entry. It is precisely from this list that a great number of the Akkadian loanwords in Ezekiel derive.[29] This is only one example of the various lines of connection Stökl draws between distinctive terminology in Ezekiel and its potential Babylonian setting. While many of the terms from the Akkadian lexical list would have been used in everyday commerce, and thus could have been “picked up” by the man on the street, the extent of the technical and even esoteric Akkadian vocabulary that finds expression in Ezekiel’s writing points to a formal exposure to the Babylonian academy and its scholarship.

Nevertheless, in spite of this suggestive evidence, it remains an open question whether Ezekiel, old enough to assume priestly duties, would, after his arrival in Babylonia, have invested years in mastering the cuneiform curriculum. What is certain, however, is that there is another group of scribes who mediated the worlds of cuneiform and alphabetic documentation, and thus confirm the multi-cultural, multi-lingual activities in which Ezekiel was engaged.

3. Alphabetic Scribes (Sepīru)

Cuneiform is a style of writing that served a number of languages (Sumerian, Akkadian, Hittite, etc.) For monumental inscriptions, the signs would be carved on stone but for standard scribal writing, the signs would be impressed by a stylus upon a clay tablet. The durability of the medium upon which cuneiform was committed matched the script’s utility and vitality. As Niek Veldhuis writes:

Cuneiform was used for three millennia; it survived fundamental historical, linguistic, and administrative changes, as well as changes in the uses of writing and it was slow to die centuries after the introduction of alphabetic systems such as Aramaic and Greek.[30]

During the period of cuneiform’s slow decline, the names of other scribal professions emerged; these were preserved in the cuneiform records, although these scribes’ writings did not survive. Cuneiform tablets, including some written at (āl-)Yāḫūdu, or nearby towns of Bīt-Našar, Bīt-Abi-râm, or Ṭūb-Yāma,[31] record the existence of a cohort of scribes competent in writing in alphabetic script(s) on the media to which those scripts were typically committed, i.e. parchment and, in the case of Egypt, papyrus.[32] In Akkadian, they were known as sepīru, a term likely borrowed from and formed on the Aramaic root s-p-r, which conveys the semantic range “to write,”[33] and from which comes the Hebrew word סופר meaning “scribe.”

Collaborative Scribes

Proof positive that cuneiform and alphabetic scribes worked collaboratively in specific contexts comes from a cuneiform text from the Hellenistic period (330-64 BCE) that notes that the text of the clay tablet duplicates the record of the transaction committed to parchment copy in the previous month:[34] the cuneiform tablet was written on 8 Simānu (=Sivan) year 84 of the Seleucid era (20 June 228 BCE), and the parchment at least a week earlier, at some unspecified time in the preceding month of Ayāru (=Iyyar).

Among the reasons for producing two copies of a transaction on two different supports is to provide members of each linguistic and script community with written confirmation of the conditions and implementation of the transaction.

The text of the earlier, parchment exemplar was undoubtedly alphabetic, Aramaic or Greek. The translation from the Babylonian to Aramaic or Greek would have been produced either with the supporting services of a translator, or by a scribe proficient in both languages and media.

Surviving evidence of sepīru and their activities suggest, as do the complexity and scope of the Babylonianisms in Ezekiel’s work, that a particular scribe could master both languages, the various media, and demonstrate competence in the multicultural environment.

Ezekiel – Parade Example of a Judahite Acculturated to Babylon

Across the network of rivers and canals that watered Babylonia, many languages and peoples came together. Whether native to the region, or resettled there involuntarily, these peoples interacted in an environment in which social and economic institutions supported varying levels of acculturation and cultural integration. Ezekiel, and the book that bears his name, provides a distinctive opportunity to explore the varieties and means of expressing these processes.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

May 21, 2017

|

Last Updated

March 10, 2025

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Dr. Laurie Pearce is a Lecturer in Akkadian in the Department of Near Eastern Studies, UC, Berkeley. She holds an M.A. and Ph.D. from Yale’s department of Near Eastern Languages and Literatures. Among Pearce’s articles are “Looking for Judeans in Babylonia’s Core and Periphery”and“Cuneiform Sources for Judeans in Babylonia in the Neo-Babylonian and Achaemenid Periods: An Overview” and she is the author (with Cornelia Wunsch) of Documents of Judean Exiles and West Semites in Babylonia in the Collection of David Sofer.

Essays on Related Topics: