Edit article

Edit articleSeries

My Abandoned Quest to Integrate Orthodoxy and Biblical Criticism

Yeshiva University's Mendel Gottesman Library, built in 1967. Wikimedia

Growing Up in an AOJS Home

I was born into a home infused with the values of AOJS – the Association of Orthodox Jewish Scientists. My father, Prof. Elmer (Eliezer) Offenbacher, cofounded this organization with a couple of colleagues in December 1947. This organization advocated a Torah u-Madda (Torah and Science) approach.[1] Two of the goals stipulated at the first AOJS meeting were: “To clarify our Weltanschauung combining a scientific and Torah outlook on the world,” and “To further ourselves professionally and socially by associating with others who have these common interests.”

My father was a solid-state physics professor for 50 years at Temple University in Philadelphia. He had grown up in Frankfurt, Germany, studied at the Samson Raphael Hirsch high school, and lived a life he referred to as “TIDES” = Torah Im Derech Eretz. Indeed, he modeled the AOJS on the idea of a pre-World War II German group known as the Bund Jüdischer Akademiker (BJA) (Union of Jewish Academicians), founded in 1906.[2] My father often asserted that the fact that we now take for granted that an Orthodox Jew can also be a successful scientist, is in no small part a product of some of the achievements of BJA and AOJS.[3]

The Torah u-Madda value system with which I grew up was also expressed in a “scientific” approach towards Torah learning, i.e., Judaic Studies. My personal interest in biblical studies began already at a young age when I would walk with my father to Shabbat afternoon study sessions at the home of Prof. Moshe Greenberg. I admired the insightful discoveries of a master teacher who represented for me an ideal of how a religious person can study Bible. [4] It seemed to me a natural next step to apply an AOJS Weltanschauung to Judaic studies and in particular to Bible. After I graduated the Talmudical Yeshiva of Philadelphia, I enrolled at Yeshiva University.

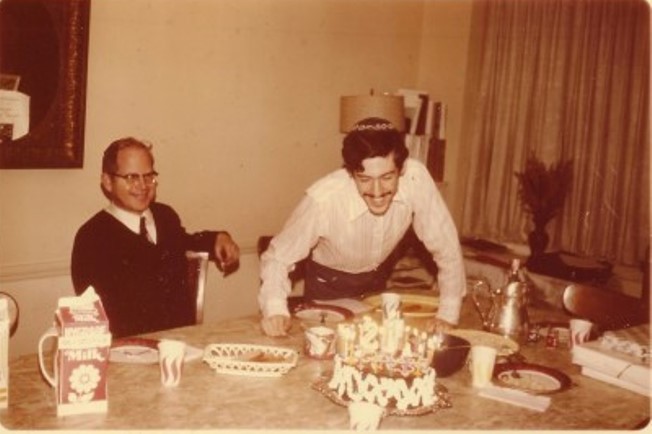

A beardless Moshe Greenberg at the author’s Manhattan apartment for his 21st birthday (March 24, 1974).

A beardless Moshe Greenberg at the author’s Manhattan apartment for his 21st birthday (March 24, 1974).

Controversies about Bible Scholarship in YU in the 60s and 70s

The validity of studying biblical criticism had been debated at YU in the mid-1960s as is reflected in letters to the editor in YU’s student newspaper, The Commentator. YU senior, Robert Koret, threw down the gauntlet in a letter on November 18, 1965, concluding: “The complex issue of a modern approach to Biblical literature must be raised again. If scholarship is the basis of a university, then scholarship must be offered”.[5]

His classmate, Irving Jabitsky, offered a rejoinder in the next issue of The Commentator (Dec 2): Biblical criticism should not have a place in Yeshiva College as it “is in a state of flux” while “the Torah is unchangeable.”[6] YU Bible professor Dr. Rabbi Meyer Herskovics[7] lectured at YU on December 2 about “the prejudice and lack of knowledge shown by some modern Bible critics.”[8] This was reported in the next installment of The Commentator (Dec 16), while also publishing an article by Larry (Lawrence) Grossman, a senior at YU, arguing that “a scholarly Orthodox approach to Bible criticism is not only consonant with Judaism, but is also urgently needed at the present time.”[9]

The next round in the debate began after Hillel Goldberg interviewed Rabbi Dr. Irving Yitz Greenberg and this was published in The Commentator April 28, 1966. Greenberg, a charismatic professor of history at YU with credentials as a Harvard Ph.D., advocated introducing “contemporary Biblical scholarship” into the YU curriculum, including comparing “the temporal experience of the ancient Near East.” He proposed developing “our own Biblical scholarship” without apologetics.

Rabbi Dr. Aaron Lichtenstein, also a Harvard Ph.D. graduate, responded criticizing Greenberg on June 6, 1966. This debate, later referred to as the “Lichtenstein - Greenberg Exchange,” is considered “a watershed in the history of American Modern Orthodoxy.”[10] The upshot was that Greenberg eventually left YU [11] and Bible criticism was not inserted into the YU curriculum.[12]

Majoring in Bible at YU

Although Bible had been part of YU’s Judaic Studies since 1917,[13] few academically trained Bible instructors taught there.[14] When YU’s Teacher’s Institute (TI) was rebranded as EMC - Erna Michael College of Hebraic Studies (today called the Isaac Breuer College), it became a college that granted B.A. degrees including in Bible. The newly appointed dean, Rabbi Jacob Rabinowitz, recruited B. Barry Levy to teach Bible studies. Levy was a 23-year-old graduate of TI studying for semicha and pursuing graduate studies at RIETS.

In fall 1970, I enrolled in Levy’s course, “Introduction to Biblical Exegesis.” It was different than my other EMC Bible courses given by Rabbis Pesach Oratz, Michael Orlian and Meir Havazelet insofar as Levy provided a glimpse into academic biblical scholarship. Not only did he demonstrate why Palestinian Aramaic Targum Neophyti was important,[15] but also introduced us to Biblia Hebraica—a Bible which notes textual variants in the LXX, Peshitta, and other places—and boldly asserted that the Torah could be clarified or “fixed” by examining textual variants.[16] I subsequently took another three courses with Levy[17] and he encouraged me to explore original research.[18]

As a Bible major at YU, I avidly studied ancient Near Eastern texts, submitted term papers such as “A Comparison of Fallen Angels in Jubilees and Enoch with Genesis 6,”[19] and read Bible criticism in the original French and German. I studiously memorized classical Greek in order to analyze the Septuagint with renowned YU scholar Prof. Louis Feldman.[20]

Perhaps inspired by Chaim Potok’s novel The Promise,[21] I visited the Jewish Theological Seminary (JTS)/Columbia University to audit Bible courses with Professors Moshe Held and Shalom Paul. I imbibed historical insights from Prof. Lee Israel Levine and heard Prof. Theodore Gaster’s explanations of his book, Thespis: Ritual, Myth, and Drama in the Ancient Near East.

The author with Nechama Leibowitz at her home (1975)

The author with Nechama Leibowitz at her home (1975)

Studying at Hebrew University

I spent the summer of 1971 in Jerusalem and wrote in my diary: “Aliyah is my dream and theoretical decision.” But it was my junior year abroad (fall 1972 - spring 1973) at Hebrew University (HU)[22] that crystallized my resolve to become a “Bible scholar.” I studied Biblical Aramaic with David Tenne, Archaeology with Amnon Ben-Tor and Akkadian with Terry L. Fenton. I took courses with leading Bible professors such as Moshe Greenberg, Nechama Leibowitz, Alexander Rofé, and Shemaryahu Talmon.

One lecturer who impressed me was 34-year-old Arie Toeg (pronounced “tveeg”), who taught Hosea. Born in Shanghai in 1938, Toeg wore a black kipah and exemplified a scholar committed to halakha who was open to honest intellectual inquiry.[23] On June 21, 1973 he told me: “It doesn’t really matter if Moses wrote the Torah or JEDP wrote it. The apologetic scholars do not truly understand the critical approach. Even Prof. Moshe Zvi Segal[24] didn’t really appreciate the complexities of the contradictory layers of biblical law…” Tragically, Toeg was killed in the 1973 Yom Kippur War.

Would it be possible to become an academic Bible scholar and remain Orthodox?[25] In the 1970s, few academic Bible scholars who identified Orthodox were involved in source criticism. The Jacobs affair in the early 1960s indicated that established Orthodoxy could not easily integrate Torah MiShamayim (Torah from Heaven) with Wellhausen.[26] Thus, I wondered if an Orthodox Jew could pursue academic biblical scholarship including higher criticism without being ostracized?[27]

My father was also concerned and wrote to me from New York:

Even in the most objective scholarly studies, personal biases have a considerable influence. This is true even in the hard sciences. Even in solid state physics, I sometimes encounter biased preconceptions and dispositions. Kal Vechomer (how much more so), one must be aware of these influences in limudei kodesh (Jewish studies). …In your studies of Tenach (Bible) and the languages and cultures of the Ancient Near East, you must continuously be aware of the “havdala” (difference) between the literary and spiritual content.

You might compare this to the two approaches used by a physician to understand his patient.[28] On the one hand, he sees his patient as an anatomical specimen… On the other hand, he relates to the patient as a human being, a tzelem Elohim (divine image) with thoughts, emotions, and a unique purpose in life.[29]

While I was at Hebrew University, the Bible Department organized a Shabbaton on May 11–12, 1973 at a hotel in Arad with the theme, “Biblical Criticism from Religious and Belief Perspectives.” The ten speakers included seven professors from the Bible Department: Moshe Greenberg, Sarah Japhet, Alexander Rofé, Emanuel Tov, Moshe Zucker, Moshe Weinfeld, and Meir Weiss, and three from the Department of Jewish Thought: Eliezer Schweid, Shalom Rosenberg, and Raphael Judah Zwi Werblowsky (who chaired their Department of Jewish Thought).

In conversation with me, Werblowsky reflected on the ensuing debates regarding how Jews should view the challenges posed by Biblical criticism, “I can observe objectively and dispassionately from a distance because I’m not religious and do not teach Bible.” During the Shabbaton, he recounted four categories of responses to Biblical criticism from a sociology of religion perspective:

- Fundamentalist—refuting science and proving faith facts;

- Protestant—separation of faith and rationalism;

- Catholic—contradiction is not possible between science and Divine Truth;

- Dialectic—mystical as a legitimate mode of interpretation.[30]

He had previously delineated these ideas in an article he wrote in response to a debate generated by Rabbi Mordechai Breuer in the Yavneh periodical Deot (1959–1960).[31] Breuer had argued that Wellhausen’s critical approach should be accepted while believing in Torah from Heaven.

Moshe Greenberg tried to explain how one can be both religious and a critical Bible scholar. He analogized this to how a child relates to a parent. When young, children innocently adore their wonderful parents. As they mature, they discover the parents’ “flaws” yet still love and admire them. So, Greenberg continued, we love the Torah, even as we discover contradictions and critical issues. We might lose our “innocence” in the pristine integrity of the Torah but not our love and appreciation.

1974 AJS – JSHS, and the Yavneh Shabbaton

In my senior year at YU, I was invited to teach a class in Ezra and Nechemia for Lincoln Square Synagogue’s adult education program. [32] I also joined other YU students in setting up a Judaic Studies Honors Society (JSHS).[33] On October 22, 1973, I met with Prof. Arnold Band, president of the AJS (Association for Jewish Studies),[34] to try and achieve recognition of JSHS.[35] He was receptive to the idea.

The highlight of my “budding Bible career” was February 15–16, 1974, in Boston. Yavneh, the Religious Students Organization, sponsored a Shabbaton on Bible Criticism at the Young Israel of Brookline. Yavneh was then in its heyday[36] and its members had tackled this topic in their Israeli journal, Deot. I invited the two Bible academics with whom I had studied at EMC: Dr. Yehuda Felman[37] and Prof. B. Barry Levy. The latter presented examples of the importance of biblical criticism based on archaeology and linguistics.

Two illustrious Boston Rabbis were invited: the Bostoner Rebbe (Rabbi Levi I. Horowitz) and Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik (Rosh Yeshiva of Yeshiva University. R. Soloveitchik spoke about his Adam 1 and Adam 2 distinction in the Torah’s first two creation stories. [38] Thanks to this talk, I defined a new category of an Orthodox response to biblical criticism for my BA thesis, “Philosophical Exegesis.” [39]

Rabbi Dr. Aaron Lichtenstein, at the time Rosh Yeshiva of Yeshivat Har Etzion, was also on the program. In fact, he was highlighted as the “mentor of Yavneh”. In 1962, R. Lichtenstein had advocated utilizing literary criticism—not textual criticism and certainly not source criticism—in line with the approaches of Israeli scholars Nechama Leibowitz and Meir Weiss.[40] Although he was in favor of integrating secular studies with Talmud Torah,[41] he was a staunch defender of the Torah as divinely revealed – “it is not merely a document delivered (salve reverentia) by God, but composed by Him.[42]

I, a naive 20-year-old YU senior, was the sixth speaker. My talk was titled “Orthodox Reactions to Pentateuchal Criticism.” Overly optimistic, I thought that the path was being paved for Orthodox Jews to actively engage in Biblical criticism.

B.A. Thesis on Torah Min Hashamayim and Pentateuchal Criticism

In January 1974, I applied for the Lady Davis Foundation scholarship for graduate study in Bible at Hebrew University.[43] On May 12 that year, I wrote a paper on Pentateuchal Criticism for Dr. David Kadosh’s EMC course in Medieval Jewish Philosophy. When Kadosh awarded me an A+, I was so enthusiastic that I expanded it into a bachelor’s Thesis, “Torah Min Hashamayim and Pentateuchal Criticism: The Variety of Orthodox Resolutions.”[44] It expanded on Werblowsky’s work by proposing seven categories of theological responses to biblical criticism:

- Axiomatic Traditionalism: Truth of tradition is superior to ephemeral hypotheses of scholars. Source criticism is considered biased and often anti-Semitic. As an example, I cited Ben Levi’s enumeration of thirteen “biases.”[45]Detractors of this approach label it “dogmatic”, “apologetic” or “fundamentalist.”

- Philosophical Exegesis: Seeming contradictions and repetitions are resolved by using philosophic tools to uncover new meanings. Rabbi Soloveitchik’s analysis of Genesis 1 and 2 is an example.

- Double Truth: There are two “universes of discourse.” Faith is supreme in the transcendental while science reigns in the physical. This “double faith” thesis, popular amongst Protestant Bible scholars, has its origins in the philosophy of Christian Averrorists, St. Thomas Aquinas and Isaac Albalag. A contemporary Israeli thinker, Yeshayahu Leibowitz, is identified with this approach. Joshua Abelson voiced this approach to higher criticism already in 1913.[46]

- Mystical Approach: The Torah is a primordial blueprint - “God looked into the Torah and created the world.”

- Scholarly Rapprochement:Reconciles the tradition of Pentateuchal authenticity with contemporary scholarship as was done in “Mosaic Maximalism” by Moses Hirsch Segal. A second example was “The Crystallization Hypothesis”, that Pentateuchal traditions were gradually deposited around a nucleus of mosaic law.

- Theological Harmonization: Belief in the Torah’s divine origin does not require the entire Torah having been verbally transmitted by Moses. For example, Franz Rosenzweig viewed the Redactor, R as Rabbeinu - his theology is our Teaching. whoever he was and whatever sources he utilized.

- Eclecticism: Selecting or combining versions of the above approaches.

On June 5, 1974, my essay won the annual YU Edward A. Rothman Memorial Essay Contest on “Application of Orthodox Judaism to Modern Times.”[47] Prof. Shnayer Z. Leiman , then at Yale University’s Department of Religious Studies, wrote to congratulate me.[48]

Rabbi Prof. Norman Lamm, who sometimes invited me to his home on Shabbat, encouraged me in my biblical pursuits. He even arranged for me to give Youth Shabbat Rabbi’s speeches at the Manhattan Jewish Center.[49] On June 13, 1974, he sent me a letter praising my B.A. thesis as “a splendid piece of work” and stating that “the paper is far too valuable to merely gather dust in your files. If there is any way in which I can help arrange for its publication, I shall be only too glad to do so.” [50] I sent my article to Rabbi Prof. Walter Wurzburger, editor of Tradition. He agreed to publish it on condition that I condense it, though, as I shall soon explain, I never did.

Spiritual Crossroad in Yeshivat Mercaz Harav in Jerusalem

When I graduated EMC, I received a second award - the Rosalie and Jacob Singer Memorial Award for Excellence in Bible,[51] and was ready to start graduate school. On June 27-28, 1974, I visited the University of Pennsylvania. Prof. Barry Eichler, Professor of Assyriology in the Department of Near Eastern Languages & Civilization, hosted me, and I also consulted with Professors Jeffrey H. Tigay and Erle Verdun Leichty. I wrote, “Now that I have decided to study at Hebrew University for my MA in Bible, I should seriously consider coming back to spend a year or two at Penn in graduate studies focusing on Assyriology.”

Before I left for Israel, Rabbi Lamm advised me to spend time immersing myself in religious studies at Yeshivat Mercaz Harav in Jerusalem before starting graduate school at HU. That advice drastically changed my direction in life.

I arrived in Jerusalem on August 14, 1974 and wrote in my diary, “I should decide if I should remain in Mercaz for a year or two or only learn for two months until the academic year begins at HU.” My first Shabbat in Jerusalem, I visited the Rosh Yeshiva, Rav Tzvi Yehudah Kook. He gave me a special blessing at seudah shlishit (the afternoon meal). I asked him how to Hebraize my name Offenbacher and mentioned that my grandfather used a nickname “Offie.” Rav Kook suggested “Ophir.” He held my hand and explained that Ophir implies preparing for holiness, for building the Beit Hamikdash [Temple] as it refers to the gold imported by King Solomon to build it (1 Chron. 29:4).

When the academic year began, I audited courses at Hebrew University. In Prof. Abraham Malamat’s class, we read texts from Mari in Akkadian and compared them to Talmudic ideas. I joined an interdisciplinary M.A. research seminar, “The Concept of Geulah in Jewish Thought”, where Prof. Moshe Greenberg presented the biblical concept of redemption. Professors Michael Stone, Eliezer Schweid, Paul Mendes Flohr and Tzvi Werblowsky examined that theme throughout history until modern times.

I especially connected to the literary criticism of Prof. Shemaryahu Talmon. On Sept. 23, 1974, I was flattered yet in a dilemma when he asked if I’d like to be his graduate assistant. I had discovered that immersing myself in full-time Torah study and tefillah [prayer] was exhilarating and a sharp contrast to the academic inquiry. At this stage in my life, my quest for biblical scholarship seemed merely a scintillating academic exercise that contrasted sharply with the spiritual fulfillment of living Judaism at Mercaz.

Besides learning Talmud Baba Batra with Rabbis Avraham Shapira, Shaul Yisraeli, Zalman Melamed, and Chaim Steiner, Rabbi Chaim Druckman excited me with the teachings of Rav Kook on prayer (Olat Rayah). Rabbi Yehoshua Zuckerman taught musar (ethics), and Rabbi Tzvi Yehudah Kook gave motzei Shabbat talks at his home. The debates of textual criticism began to seem irrelevant in the world of פנימות התורה (inner spiritual secrets of Torah) in a Yeshiva whose goal was to encourage each of us to live as a “Tzadik.”

On May 2, 1975, I consulted Rav Tzvi Yehudah Kook for advice about enrolling at HU while continuing at Mercaz. He responded unequivocally, “It is frivolity and even destructive.” He counseled me, “Our Yeshiva is educating for belief (emunah) while the University is teaching disbelief and heresy (apikorsut and kefira).”[52] He stipulated that he was not negating individuals at Hebrew University, and mentioned Prof. Shraga Abramson (a Talmud Professor) as an example of an outstanding scholar filled with yirat shamayim (fear of Heaven).”

Rav Kook’s strong language shocked me to invest my full energy and time learning Torah.[53] I decided to remain in Mercaz Harav to “fill myself with holiness and spirituality.” I also decided against publishing my paper in Tradition, given R. Kook’s depiction of such study as destructive and heretical. I began studying for Rabbinical ordination.

In January 1978 I was ordained by the Roshei Yeshiva of Mercaz Harav, Rabbi Avraham Shapira, and Rabbi Shaul Yisraeli as well as from Rabbi Yehudah Gershuni, Dean of Yeshivat Eretz Israel, and Rabbi Avraham David Rosenthal, Rosh Yeshiva of Keter Torah.

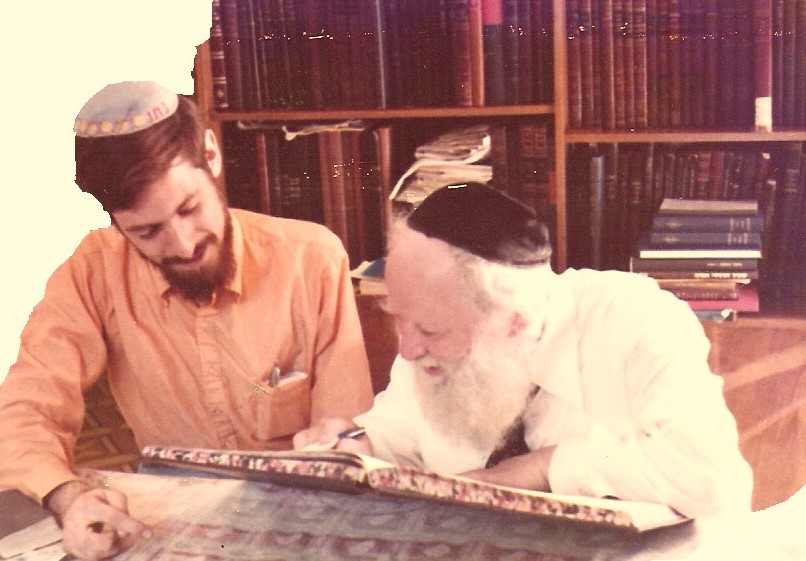

Author studying Talmud with Rabbi Avraham Shapira, Rosh Yeshiva of Mercaz Harav and later Chief Rabbi of Israel.

Author studying Talmud with Rabbi Avraham Shapira, Rosh Yeshiva of Mercaz Harav and later Chief Rabbi of Israel.

A Career in Jewish Education and Jewish Philosophy

In August 1979, I got married and began an educational career. I set up a program for English speakers at Yeshivat Machon Meir, taught מחשבת ישראל (Jewish Thought) at the Horev high school for girls and at the Mercaz Harav high school for boys as well as to one year program students at BMT (Beit Midrash LeTorah).

In September 1981, I returned to Hebrew University, but chose the Melton Program of Jewish Education in the Diaspora as a less problematic area than Bible studies. I reestablished the Yavneh Student Organization on campus and organized religious activities. I was still grappling with the yeshiva/university dichotomy and even gave a talk in January 1982 for Hebrew University Rothberg Overseas School students titled “University or Yeshiva: Where Do They Differ?, in which I compared Albert Einstein’s ideal for Hebrew University[54] with that of Rabbi Avraham Yitzhak haCohen Kook.[55]

A year later, the University decided to employ a full-time coordinator of religious affairs. The Dean of Students, Prof. Amiran Gonen, who knew me via Yavneh, hired me for that on Oct. 17, 1982.[56] Besides the rabbinic halachic responsibilities and pastoral counseling to the University community, I also set up a Beit Midrash and Kollel Program. I organized dozens of symposia and weekend retreats, developed Gesher encounters between religious and non-religious students, officiated at many weddings, and developed interfaith programming. Throughout, my mentors at Mercaz Harav encouraged me to do “outreach” on the college campus. On Sept. 13, 1987, Rav Avraham Shapira, Israel’s Chief Rabbi, even granted me an official document of recognition as Rabbi of the Hebrew University Mt. Scopus campus.

Returning to Graduate Studies… but not Bible

In 1984, I decided to switch from Jewish Education to a more content-based discipline. Academic Bible study had lost its luster and appeal for me and there was no TheTorah.com in those days. Instead, I was attracted to the work of professors in the Jewish Philosophy Department including Prof. Aviezer Ravitsky who later became my M.A. and Ph.D. advisor. He confided in me that he too had decided not to major in Bible because he felt that it would undermine his faith in religious Judaism.

|

|

|

The author with Profs. Aviezer Ravitsky & Zeev Harvey, World Congress of Jewish Studies, June 1993. |

The author with Prof. Jacob Elbaum in his office at Hebrew University, Mt. Scopus, July 1993. |

I found Ravitsky’s course on Hasdai Crescas fascinating and intellectually challenging. I also found a second advisor, Prof. Yaakov Elbaum, with whom I studied Rabbinic midrashic literature. Under their guidance, I completed my M.A. and Ph.D. about Rabbi Hasdai Crescas as a Philosophical Exegete of Rabbinic.

In a way, I had returned full circle, but in a safer venue. Crescas was famous for offering an alternative to the 13 principles of faith as defined by Maimonides and did not include dogmas #7-9 which had set the foundation for the axiomatic belief in Torah Min Hashamayim.[57]

What If There Had Been TheTorah.com?

In retrospect, TheTorah.com encapsulates my quest of half a century ago: to utilize tools and insights of academic biblical scholarship to deepen engagement with the Torah as a living text in a modern world. It is something that nowadays is becoming normative, [58] but half a century ago was possible only for a dedicated few.[59] But what impact will expansive engaging in biblical criticism have upon the fabric of future Modern Orthodoxy? Will it “lead to attrition, out of Orthodoxy and out of halachic observance?” Has the belief in the divine origin of the written Torah become such an integral part of Orthodox theology that Orthodox Jews who are biblical critics will ipso facto be ostracized?[60]

Now to return to my opening story, can a comparison for TABS be drawn to what AOJS and BJA did in enabling Orthodox Jews to integrate into the academic world of science? The common theme is an honest intellectual inquiry combining “a scientific and Torah outlook on the world” with a framework of social support. Is TheTorah.com performing a similar role for scholars of modern academic Bible study?[61] Are we witnessing the emergence of an Internet based global community of Bible scholars? Or to use my father’s nostalgic German/Yiddish expression, is TheTorah.com creating a “Chavershaft” of kindred souls working together towards a common goal synthesizing Torah and Mada?

The answer is not so simple because the theological challenges raised by biblical criticism, which go to the very foundation of Judaism, seem more problematic and “dangerous” than those raised by science.[62]

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

November 11, 2021

|

Last Updated

February 2, 2026

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Dr. Rabbi Natan Ophir (Offenbacher) is currently the Head of the English Department at Emunah Academic College of Fine Arts in Jerusalem. An alumnus of Yeshiva University, he received ordination from Yeshivat Mercaz Harav and a Ph.D in Jewish Philosophy at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. In addition to his many articles, Ophir is the author of Rabbi Shlomo Carlebach: Life, Mission, and Legacy (Urim 2014). In the past, he directed JMIJ, the Jewish Meditation Institute Jerusalem, to teach Jewish Meditation in the light of neuropsychology.

Essays on Related Topics: