Edit article

Edit articleSeries

Reconstructing the Features of Solomon’s Temple

A clay and stone model found at Khirbet Qeiyafa. Qeiyafa.huji.ac.il

As no archaeological excavations can be performed on the Temple Mount, the biblical text describing Solomon’s Temple is our only source about that building. Three long chapters in the book of Kings provide varied information about the form of the Temple, the size of the different rooms, its construction materials, its decoration, its major cultic paraphernalia and its dedication ceremony.

Many of the passages’ architectural details describing the Temple are difficult to understand. Until recently, these questions could only be debated theoretically, as no empirical finds could be brought to bear on the question. All this changed in 2011, with the excavations at Khirbet Qeiyafa.[1]

Qeiyafa and the Stone Temple Model

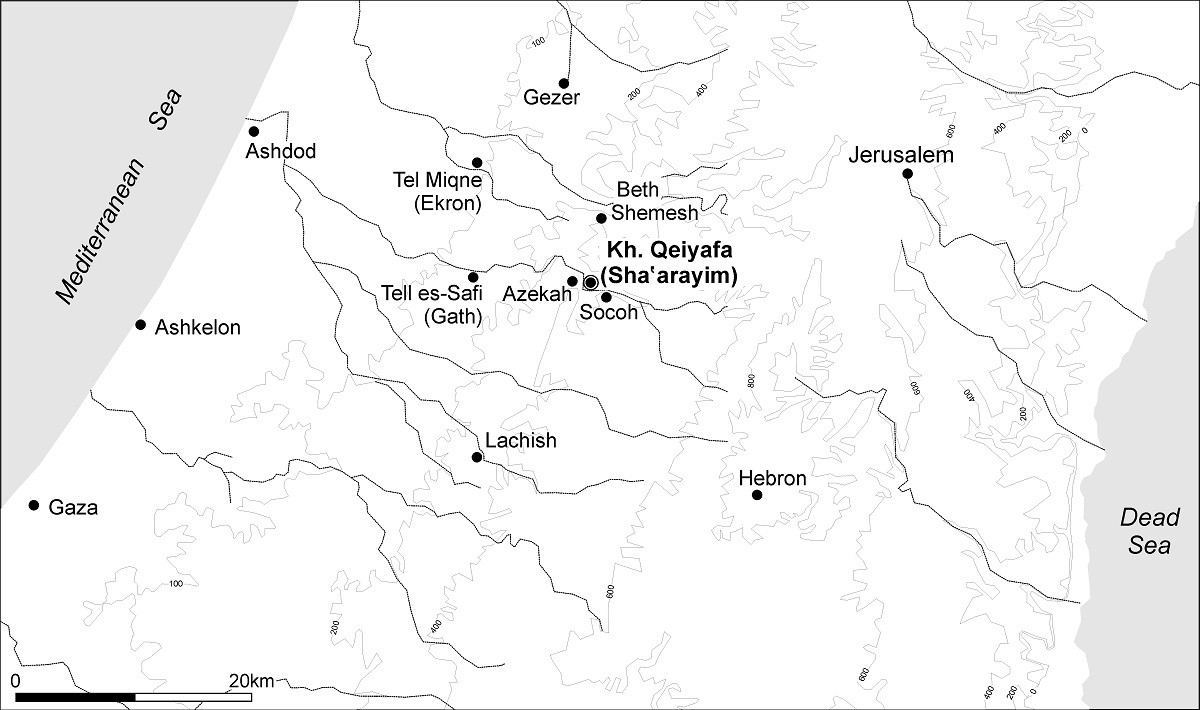

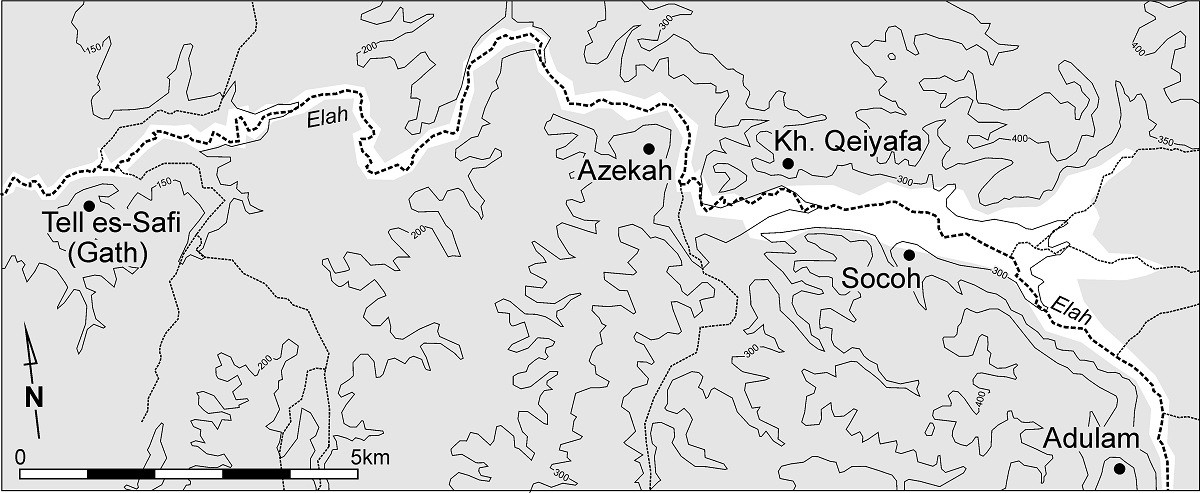

The ancient city of Khirbet Qeiyafa is located in the Judean lowlands on a ridge that encloses the Elah Valley from the north.

Close by in the valley are other archaeological sites, such as Tel Socoh to the east and Tel Azekah to the west. The famous battle between David and Goliath of Gath is also set in the Elah Valley near Khirbet Qeiyafa, at Ephes-dammim between Socoh and Azekah (1 Samuel 17:1).

During seven seasons of excavations, we uncovered a fortified city that was built in the early 10th century B.C.E. i.e., which according to the biblical chronology is the time of King David.

While excavating a cultic room near the southern city gate, we uncovered a unique shrine model made of stone. Such models are miniature buildings to contain cultic artifacts. The very fact that this object was carved in stone is unusual, because such objects found so far had been fashioned out of clay by potters. (In fact, nearby, another shrine model was found, made from clay.)

The stone model is a carved box, 21 cm wide, 26 cm long, and 35 cm high.

The figure above shows the object’s façade after reconstruction. The sides and back are simple flat walls, while the façade is elegantly profiled. In the center of the façade is a large rectangular doorway, 10 cm wide and 20 cm high. Chiseled upon the structure’s ornate façade are a number of architectural elements: a triple recessed doorway and triglyphs. As we studied the architectural style represented in the model, it emerged to our surprise that these components appear in the biblical description of Solomon’s Temple.

Triple Recessed Doorway

The model’s entrance has three interlocking frames: the outer frame is the largest, the middle frame is smaller and recessed from the first toward the interior of the model, and the inner frame is the smallest, again recessed from the first two. This triple-recessed doorway forms three rows of lintels above the entrance and three rows of doorposts on either side. A fourth frame, which extends to the top of the structure, apparently represents the edge of the building, but may indicate a fourth outer doorframe.

This recessed doorway casts light on the description of the entrance from the forecourt (ulam) to the outer sanctum or great hall (hechal) in the book of Kings:

מלכים א ו:לג וְכֵן עָשָׂה לְפֶתַח הַהֵיכָל מְזוּזוֹת עֲצֵי שָׁמֶן מֵאֵת רְבִעִית.

1 Kgs 6:33 For the entrance of the forecourt, too, he made doorposts of oleaster wood, having four sides.

The Hebrew מֵאֵת רְבִעִית is difficult and means something like “in a fourfold way”; it is often emended to read רְבֻעוֹת. The Greek LXX interprets the phrase (or an alternative Hebrew text) as στοαὶ τετραπλῶς, meaning “four-sided porticos.” Looking at the model, we suggest the meaning is that the entrance had four mezuzot (doorposts).

According to Kings, the entrance between the outer sanctum and the inner sanctum/shrine or holy of holies (devir) had five mezuzot (doorposts) of olive wood:

מלכים א ו:לא וְאֵת פֶּתַח הַדְּבִיר עָשָׂה דַּלְתוֹת עֲצֵי שָׁמֶן הָאַיִל מְזוּזוֹת חֲמִשִׁית.

1 Kgs 6:31 For the entrance of the inner sanctum he made doors of olive wood, the pilasters and the doorposts having five sides.

The elaborate stone shine model from Khirbet Qeiyafa, which includes a doorway ornamented with recessed frames, clearly shows that temple entrances could indeed be decorated with multiple recessed doorframes, i.e., mezuzot.

Recessed Doorframes in the Ancient Near East

This design is known from many structures in the ancient Near East. The earliest example of such recessed openings is from Tepe Gawra in Mesopotamia, dated to around 4500 B.C.E., in three temples that stood in the city square.

Dozens of doorways like this are known from excavations in Mesopotamia, dated to the fourth, third, second, and first millennia B.C.E., mainly in temples.

In fact, they were so typical of temple entrances that eventually they became a symbol of a temple and of the presence of the deity in his temple. In our study on recessed doorways in temples, and other buildings of worship, we followed this motif from 4,500 B.C.E. till today.[2]

The only examples known to us of this motif in Israel are from Khirbet Qeiyafa. Both are unique cult objects. The first is the stone model discussed here at length. The second is a basalt altar decorated on its narrow side like the façade of a structure including a doorway around which a number of frames were carved, representing recessed frames.

Thus, it would appear that this construction style reached the Land of Israel only in the Iron Age, and that Canaanite culture of the Middle and Late Bronze Age did not commonly decorate temple doorways with recessed frames; certainly none of the great Canaanite temples found in various places in the country, such as Hazor, Megiddo, Shechem, and Lachish, used this motif. These Canaanite Bronze age temples agree with most Assyrians and Egyptian temples, which also lacked this motif.

Triglyphs

A row of protruding rectangular elements can be found between the doorframe and the roof of the model. Each is divided by deep incisions into three smaller parallel rectangles. Four such protruding rectangles were fully preserved, and remains of three others are visible, together creating seven such elements. This element depicts the wooden beams that support the roof and is called a “triglyph”; it is a common feature of classical architecture of Greek temples.

The triglyph decoration in the temple model from Khirbet Qeiyafa predates the Greek temples by several centuries; for example, it is about half a millennium earlier than the Acropolis temples of Athens. The evidence from Khirbet Qeiyafa suggests that the triglyph motif began no later than the early tenth century B.C.E., much earlier than previously supposed.

This too sheds light on the biblical text, which uses the expression tzelaot (צלעות) in various contexts in the description of the Temple. In general, the term refers to wooden planks, for example in “planks of cedar” and “planks of cypress.”

מלכים א ו:טו וַיִּבֶן אֶת קִירוֹת הַבַּיִת מִבַּיְתָה בְּצַלְעוֹת אֲרָזִים מִקַּרְקַע הַבַּיִת עַד קִירוֹת הַסִּפֻּן צִפָּה עֵץ מִבָּיִת וַיְצַף אֶת קַרְקַע הַבַּיִת בְּצַלְעוֹת בְּרוֹשִׁים.

1 Kings 6:15 He paneled the walls of the House on the inside with tzelaot of cedar. He also overlaid the walls on the inside with wood, from the floor of the House to the ceiling. And he overlaid the floor of the House with tzelaot of cypress.

1 Kings suggests that such planks were used to panel the interior walls of the outer sanctum and the holy of holies. 1 Kings 6:5 also describes planks surrounding the outer sanctum and the holy of holies near the roof:

מלכים א ו:ה וַיִּבֶן עַל קִיר הַבַּיִת (יצוע) [יָצִיעַ] סָבִיב אֶת קִירוֹת הַבַּיִת סָבִיב לַהֵיכָל וְלַדְּבִיר וַיַּעַשׂ צְלָעוֹת סָבִיב.

1 Kgs 6:5 On top of the outside wall of the House—the outside walls of the House enclosing the Great Hall and the Shrine—he made tzelaot all around. (authors’ translation).

Many translations, such as NJPS, NRSV, KJV, have interpreted the term tzelaot to mean “side chambers.” Nevertheless, we suggest that this is a mistaken translation, and that this is describing the use of wooden planks that support the roof.

Support for this translation comes from Ezekiel, which describes the Temple with tzelaot, in groups of three, thirty times, surrounding the Outer Sanctum and the Holy of Holies:

יחזקאל מא:ו וְהַצְּלָעוֹת צֵלָע אֶל צֵלָע שָׁלוֹשׁ וּשְׁלֹשִׁים פְּעָמִים וּבָאוֹת בַּקִּיר אֲשֶׁר לַבַּיִת לַצְּלָעוֹת סָבִיב סָבִיב לִהְיוֹת אֲחוּזִים וְלֹא יִהְיוּ אֲחוּזִים בְּקִיר הַבָּיִת.

Ezek 41:6 And the tzelaot (planks) were organized three together, in thirty groups, placed on top of the wall, around all the building, without being integrated into the walls of the building.

Again, the preferred translation here has been “side-chambers,” but we suggest that Ezekiel presents the tzelaot as wooden planks organized in groups of three, like the triglyphs in the Khirbet Qeiyafa temple model. The same accounting relating to the tzlaot in the description of Solomon palace:

מלכים א ז:ג וְסָפֻן בָּאֶרֶז מִמַּעַל עַל הַצְּלָעֹת אֲשֶׁר עַל הָעַמּוּדִים אַרְבָּעִים וַחֲמִשָּׁה חֲמִשָּׁה עָשָׂר הַטּוּר.

1 Kgs 7:3 It was roofed with cedar above the tzlaot (planks), which were placed on top of pillars, 45 planks in 15 groups.

In short, the biblical tzelaot near the roof of monumental buildings, like a palace or a temple, are organized in groups of three together. This is the contribution of the Khirbet Qeiyafa shrine model to a better understanding of the text.[3]

According to the ratio of spacing beams in the Solomon’s palace, we reconstruct that the beams were placed 4 cubits apart. We reconstructed 10 groups of beams on each side of the structure and 5 on the front and 5 in the back. Thus, there were 30 groups of beams around the entire building. Precisely the number mentioned in the book of Ezekiel (41:6).

Windows

Although many scholars did not include windows in their reconstruction of the temple, it is clear that the Temple had windows; the text mentions them explicitly:

מלכים א ו:ד וַיַּעַשׂ לַבָּיִת חַלּוֹנֵי שְׁקֻפִים אֲטֻמִים.

1 Kgs 6:4 He made windows for the House, šequfim and ʾaṭumim.

The meaning of the verse is difficult: The word šaquf generally means “transparent” while ʾaṭum means “opaque.” How can windows be both transparent and opaque? The King James Version translates it as “windows of narrow lights” and the New Jewish Publication Society Tanakh translates these terms as “recessed and latticed.”

We understand the term as windows with recessed window frames, as Yigal Yadin suggested long ago.[4] Such windows are engraved on many ivories which depict a woman looking through a window.[5] While the model does not have windows, it has recessed openings, parallel to the recessed frames around the Temple windows.

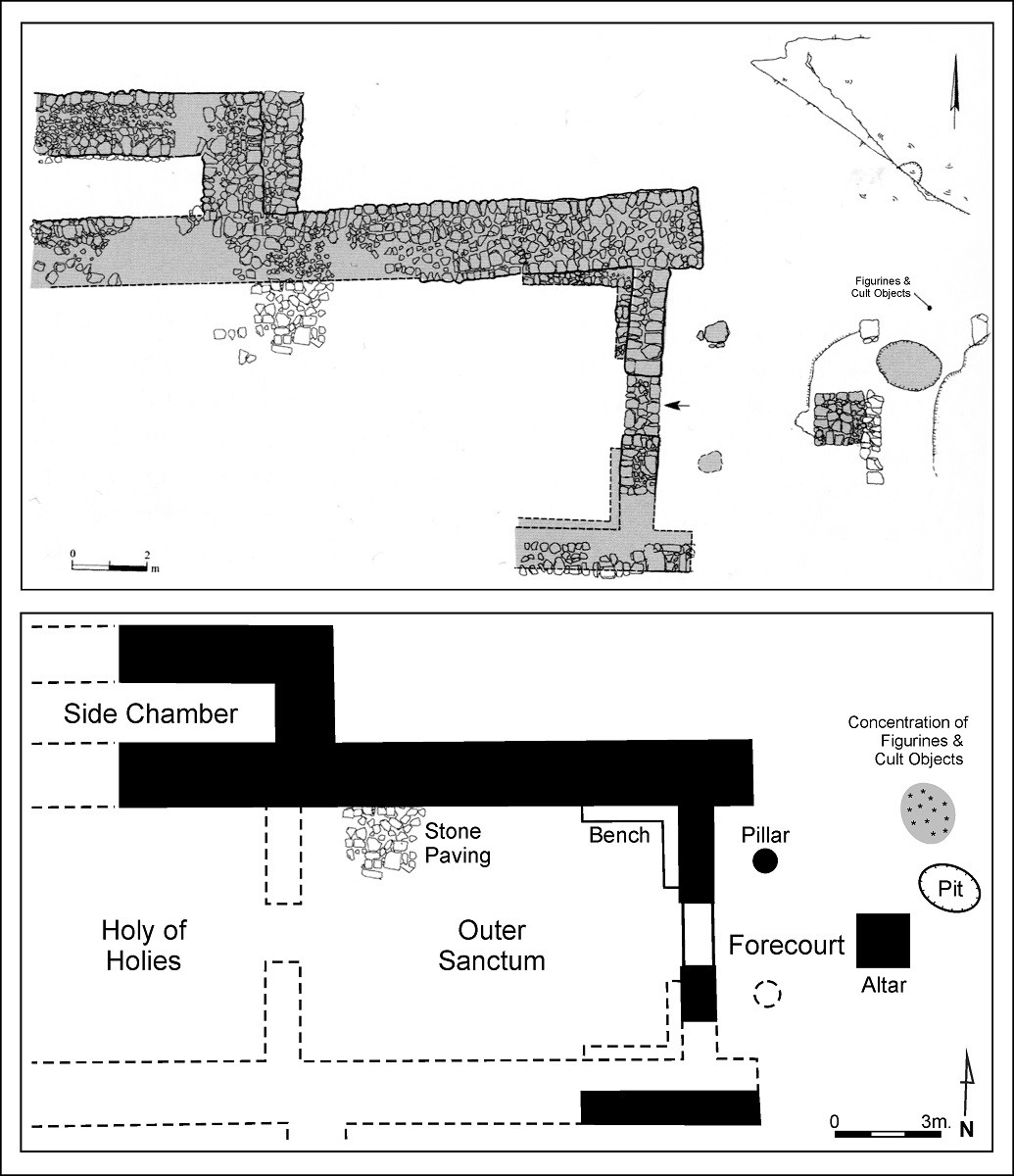

The Motza Temple

In 2012, less than a year after the temple model was found at Khirbet Qeiyafa, a ninth century B.C.E. temple was found at Motza near Jerusalem.[6] Both the Motza temple and the Jerusalem Temple existed simultaneously, and thus the former can help us better understand the biblical text relating to the Solomonic Temple.

The structure at Motza faced east and included two columns at the front, a Forecourt (Ulam), an Outer Sanctum (Hechal) and probably part of the Holy of Holies (Devir).

It also features an outer structure surrounding it on the western side. Thus, the Motza temple conforms in all aspects to the biblical description of Solomon’s Temple in Jerusalem.

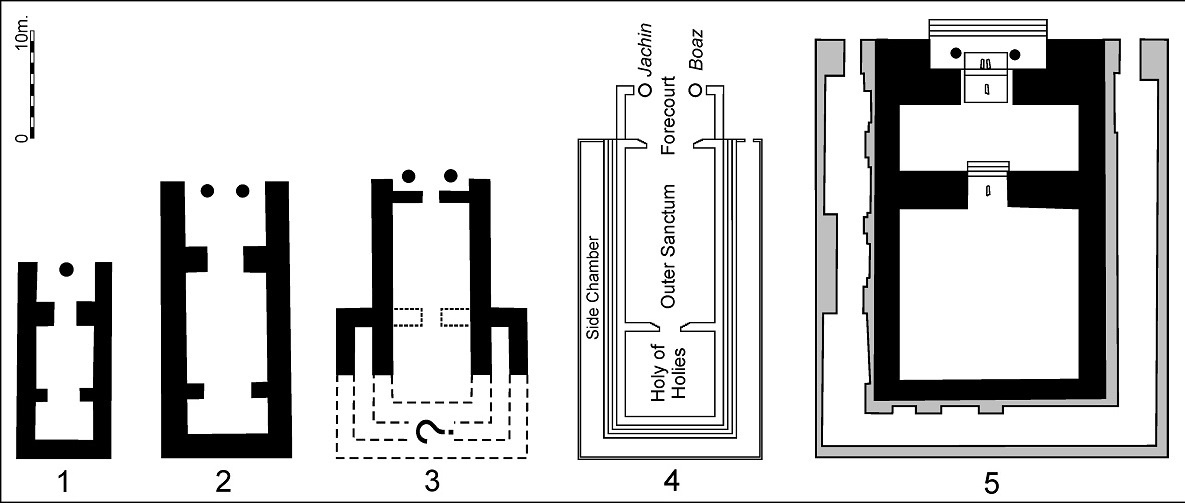

Archaeological excavations have uncovered similar temples that illuminate the cultural background shared with the temple in Jerusalem, such as the temples at tell Tayinat in Southern Turkey, the temple at tel Arad and the temple at Ain Dara in northwestern Syria.

Indirect Archaeological Light on Solomon’s Temple

With the discovery of the stone model in Qeiyafa and the Motza Temple, it is possible to discuss Solomon’s Temple based on information derived from sites that are close to it, both geographically and from the biblical perspective, chronologically. The Motza temple helps us understand the horizontal plan of Solomon Temple, while the Khirbet Qeiyafa building model helps us understand the vertical shape of the building.

Built in the Tenth Century B.C.E.?

For the past few decades, scholars have long debated whether the Temple was really built in the late tenth century, when King Solomon ostensibly ruled in Jerusalem. The findings in Qeiyafa and Motza shed some light on this question.

The description of the Temple built by King Solomon in 1 Kings 6 reflects some of the main characteristics of royal architecture in the Levant in the 10th – 7th centuries B.C.E. Enigmatic passages suddenly make sense when interpreted through the prism of these archaeological examples. This, in turn, demonstrates that the writer of 1 Kings 6 was aware of this particular type of architecture, unknown in the Levant before the era of David and Solomon. The Khirbet Qeiyafa shrine model is a direct evidence that this building style was known in Judah in the 10th century B.C.E.

One of the main functions of the historian is to compare and cross-reference sources. If different sources attest independently to the same phenomenon, the historical reliability of that phenomenon is greatly enhanced. Thus, the discovery of the stone temple model at Khirbet Qeiyafa and the temple at Motza make it more plausible that a similar temple could have been built in Jerusalem in the same period.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

August 5, 2019

|

Last Updated

March 23, 2025

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Dr. Madeleine Mumcuoglu is a research fellow at the Institute of Archaeology, the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, where she specialized in the cultic architecture of the Ancient Near East. She holds a doctorate from the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich (ETH Zurich), and has participated in the excavations at Khirbet Qeiyafa, Lachish, and Khirbet al-Rai. Mumcuoglu is the co-author (with Yosef Garfinkel) of Solomon’s Temple and Palace: New Archaeological Discoveries and Crossing the Threshold: Architecture, Iconography and the Sacred Entrance.

Prof. Yosef Garfinkel is Yigael Yadin Professor of Archaeology of the Land of Israel at the Institute of Archaeology, the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, where he has been the head since 2017. In the early part of his career, he specialized in the late prehistory of the Levant, the Neolithic and Chalcolithic periods. As part of this work, he excavated various Proto-historic sites such as, Yiftahel, Gesher, Tel Ali, Shaar Hagolan, Neolithic Ashkelon, and Tel Tsaf. Since 2007, he has shifted his concentration to the early phases of the Kingdom of Judah in the 10th and 9th centuries B.C.E. As such, he has conducted excavations and surveys at Khirbet Qeiyafa, Socoh, Tel Lachish and Khirbet al-Rai, uncovering new data on the early kings of the kingdom: David, Solomon, and Rehoboam.

Essays on Related Topics: