Edit article

Edit articleSeries

The Ancient City of Hebron

Credit: Dr. Avishai Teicher Pikiwiki Israel

An Ancient City – Older than Tanis

When Moses sends spies to scout out the land, one of the places they arrive at is the city of Hebron:

במדבר יג:כב …וְחֶבְר֗וֹן שֶׁ֤בַע שָׁנִים֙ נִבְנְתָ֔ה לִפְנֵ֖י צֹ֥עַן מִצְרָֽיִם:

Num 13:22 …Now Hebron was founded seven years before Zoan of Egypt.

According to the verse, Hebron is more ancient that the Egyptian city of Zoan, the Hebrew name for Tanis (Egyptian Djanet). Tanis was built during the Ramesside 19th dynasty (ca. 1292-1189 B.C.E.), and eventually became the capital of Egypt during the 21st dynasty (ca. 1069-945 B.C.E.), as the Nile changed course away from Pi-Ramesses.

By making Hebron a little older than Tanis, probably the “old” capital of Egypt at the time the verse was written, the biblical author wished to communicate Hebron’s antiquity; yet Memphis, Thebes and Heliopolis would have been better choices.[1] In fact, according to the archaeological remains, Hebron is much older than Tanis.

Tel Hebron: An Overview

Ancient Hebron is not in the modern city of Hebron, which lies in the valley near the Cave of the Patriarchs in an area built during the Mumluk period (probably during the 13th century C.E. or later). Instead, it is located on Tel Hebron (often erroneously called Tell Rumeida), which lies on a secondary eastern spur of Jebel Rumeida (elevation 936 m = about 3000 feet above sea level), overlooking the modern city of Hebron from the south.

Topographically, the mound is not easily defensible, but it is situated near a cultivation area and, importantly, near a spring which until the Ottoman period was called “En Hebra” (spring of Hebron), though today it is called En Judeida, (Arabic for “the new spring”). This setting on a lower spur, near a spring, recalls the site at the City of David built adjacent to the Gihon Spring at Jerusalem.

After it was abandoned, probably during the Islamic period, the mound gradually became covered by agricultural terraces. The tell is covered today mostly by olive groves, some hundreds of years old. What do we know about the history of this ancient town?[2]

Biblical Period Hebron – According to the Bible

Hebron was (and still is) the foremost city in the Judean hill country south of Jerusalem. The name Hebron likely derives from the Hebrew root ח.ב.ר, meaning “friend.” The name is known from ancient stamp seals (see discussion further on) as well as from the Bible. Biblical texts also identify Hebron with Kiryat-Arba and Mamre (e.g., Gen 13:18, 23:2), which has led some scholars to suggest that the town was constructed of various quarters (possibly four, as the Hebrew name Kiryat-arba may indicate) with different names, and thus spread overa relatively large area.[3]

Hebron in the Abraham Story – Hebron plays a prominent role in the Abraham stories. In addition to his building an altar to YHWH there, by Elonei Mamre (Oaks of Mamre, Gen 13:18), Genesis describes how Abraham bought a field, with a burial cave called Machpelah, from one of its Hethite (or Hittite) inhabitants.[4] The purchase takes place before “all who entered the city gates” (לְכֹל בָּאֵי שַׁעַר עִירוֹ), implying this was a walled city. As such, a field used for burials would have been located outside the city walls. According to Genesis, this cave became the burial place of all three patriarchs and three matriarchs (Gen 50).

Hebron Becomes Israelite/Judahite – The Bible contains multiple somewhat discordant references to the conquest of Hebron. Two of these passages describe how Joshua conquered it either in the southern campaign (Josh 10:36-37), or in a campaign to clear the land of giants (Josh 11:21). Another three passages describe how the city was given to Caleb and his descendants (the Calebites) and how he conquered it (Josh 14:13–15, 15:13-14, Judg 1:10).

Hebron’s Many Functions in Judah – Hebron is described as a city of refuge (Josh 20:7, 21:13), as a Levitical city specifically for priests (Josh 21:11–13, 1 Chron 6:39-40), and as a “city of defense” (עָרִים לְמָצוֹר) in Judah fortified Solomon’s son, Rehoboam (2 Chron 11:10).[5]

David’s First Capital – The Book of Samuel describes Hebron as David’s first capital, where he ruled for seven and a half years before his conquest of Jerusalem (2 Sam. 2:1–4, 5:3–5). When David executes the killers of Ish-boshet, Saul’s son, he chops off their hands and legs and displays them over the “pool at Hebron” (עַל הַבְּרֵכָה בְּחֶבְרוֹן; 2 Sam. 4:12, possibly the spring near Hebron). Later, in the story of Absalom’s rebellion, as an excuse to go to Hebron where he launches his rebellion against his father, Absalom claims that he needs to go to there to “pay his vow before YHWH” (2 Sam. 15:7–12), implying there was a cultic site there.

All of these references reflect the importance of Hebron at their authors’ time.

Biblical Period Hebron – According to Archaeology

As noted above, archaeology has demonstrated that Hebron is a very ancient city.

Early and Middle Bronze Age (Canaanite City)

Already in the Early Bronze Age III (ca. 2600–2200 BCE), the city was fortified with a massive twenty-foot thick city wall, which was exposed by Emanuel Eisenberg underneath the even more massive Middle Bronze Age city.

Philipp Hammond was the first archaeologist to excavate Hebron, during the 1960’s. In the southern part of the tell, Hammond exposed portions of the cyclopean city wall,[6] which he dated to the Middle Bronze Age.[7] Avi Ofer followed during the 1980’s, and Emanuel Eisenberg in 1999 exposed another segment of the same city wall on the northern side of the tell and, using pottery and scarabs from the related floors, securely dated it to the Middle Bronze Age II (1750–1550 BCE).[8]

The Middle Bronze Age wall exposed on the south side is nearly 200 feet of continuous wall. Several other MB sites in the central hills were fortified by similarly sized walls, as Jerusalem-the City of David, Shechem and Shiloh. The wall stood about 15 feet high in places, nearly 12 feet thick, but was probably originally at least double in height. This massive city wall, built of huge rocks (up to six feet in size), would have been visible from afar to passersby.

Some scholars have suggested that this cyclopean wall is the reason Hebron developed a reputation as a city originally built by (mythical) giants (ʿanaqim),[9] though other scholars have offered a more prosaic suggestion that that the original meaning of ʿanaq was not “giant” but a clan name, related to the Amorite clan yʿnq mentioned in second millennium B.C.E. sources.[10]

Iron Age (Israelite Hebron)

But what was Hebron like in the Iron Age, some 700–1000 years later, during the period in which the Hebrew Bible stories about Hebron were likely composed? New excavations conducted by the author and Emanuel Eisenberg indicate that the massive fortification existed then as well, and that they were used and even reinforced during the First Temple period continuously, up until the last days of the kingdom of Judah in the early 6th century B.C.E.[11]

An enforcement or supporting wall running along the outside of the entire city wall, fortified by a tower, was discovered. Adjacent to it was a glacis, a sloping rampart designed to make it difficult for enemies to climb the wall or attack it with battering rams. Six feet to the south yet another massive wall was built parallel to the city wall.

These additional fortifications date to the 8th century B.C.E. or later; the date was obtained from pottery and other finds from the fill of the enforcement walls. Possibly the wall was built during the days of Hezekiah, who rebelled against Judah’s Assyrian overlord Sennacherib.

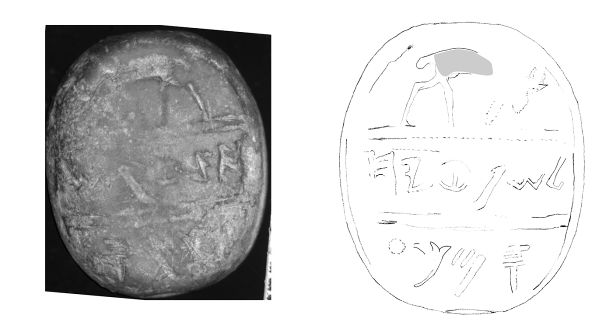

The Seal of Shephatyahu

The Iron Age fortification area yielded a Hebrew seal with a picture of a grazing deer, underneath which it reads:

לשפטיהו סמך

Of Shephatyahu (son of) Samekh

According to the style of the letters as well as parallels for the name and decoration the seal should date to the late 8th or early 7th century B.C.E.[12] The motif of the grazing deer/gazelle crouching towards the ground (on the upper register) is popular on private seals of officials in Judah during the late Iron Age II. It may symbolize dedication and devotion as well as the “one beloved by God” as we find, for instance, in Psalms:

תהלים מב:ב כְּאַיָּל תַּעֲרֹג עַל אֲפִיקֵי מָיִם כֵּן נַפְשִׁי תַעֲרֹג אֵלֶיךָ אֱלֹהִים.

Ps 42:2 Like a hind crying for water, my soul cries for You, O God.

The first name is a standard Yahwistic name meaning “YHWH has obtained justice.” The name here appears in its full form (-yahu), as was standard in Judah during this period, as opposed to its short form (-yah).[13] Both forms of this name (Shephatyahu and Shephatya) appear in the Bible (the latter is more common).

The second name is a hypocoristic theophoric name, in other words, a shortened form a theophoric (god-based) name with the divine element removed. The name means “[X] has supported.” One form of the name, Aḥisamakh—using the element “my brother” (a familial epithet for God)—appears in the Bible as the patronymic for the leader of the tribe of Dan (Exod 31:6).

The seal probably belonged to one of the officials of Hebron, maybe the one responsible for the fortification work. Hebron was an important administrative site during the late Iron Age, and this is reflected in the well-known LMLK (lamelech), “for the king,” seals stamped onhundreds of jar handles from the time Hezekiah.

The jars have been found in many locations, and they are generally marked with the name of one of four towns: Hebron (חברן), Mamshit, Zif, or Sochoh. Many of the seals also carry a royal emblem of a two- or four-winged figure.[14]

The lamelech seals were produced in one center in the Shephelah, and probably relate to an emergency tax collection taken by Hezekiah in preparation for the confrontation with the Assyrians, perhaps to supply emergency provisions to various districts.

Persian and Early Hellenistic Periods

The Iron Age city of Hebron and its massive wall were destroyed in the early 6th century B.C.E. by the Babylonians under Nebuchadnezzar. After a brief period of abandonment, the city was reoccupied by the Idumeans (biblical Edom), who, taking advantage of the absence of the Judeans, had begun to expand from southern Transjordan to the west and north, eventually reaching all the way up to Ashkelon-Beth Zur on the coast. By the time Judea was re-established in the Persian period, Hebron and its surroundings had already been assimilated into Idumea, which continued to dominate this region during the Hellenistic period as well.

The book of 1 Maccabees (5:65) describes how Judah the Maccabee fought the Idumeans who occupied Hebron:

And Judah and his brothers went out and made war on the sons of Esau in the land to the south. And he struck Hebron and its daughters and tore down its fortresses and burned the towers all around it (NETS with adjustments).

Later, After the successful Maccabean revolt and the founding of Judea as an independent polity, Josephus writes (Ant. 13:9) that the Hasmonean high priest John Hyrcanus, who ruled Judea, conquered the Idumeans and forcibly converted them to Judaism (c. 125 B.C.E.).

Late Hellenistic and Roman Period Hebron – Jewish or Idumean?

Considering that Hebron was an Idumean town, but that Idumea was ruled by Judah and the Idumeans had been converted to Judaism, was Hebron a Jewish town during the late Hellenistic and Roman periods? Archaeology can shed some light on this question.

The Cave of the Patriarchs Monument

For the past two millennia, the Cave of Machpelah has been identified with what is now called the Cave of the Patriarchs (in Arabic: al-Ḥaram al-Ibrahimi or Ḥaram el-Khalil). The cave itself has never been excavated, but various pieces of evidence such as pottery dated from the Iron Age and probably earlier, indicate that it contains (or once contained) ancient burials.[15]

Above this cave sits a Roman Period temenos (cultic site), a large monument built of ashlar stone. From the style of construction, it is clear that it was built by King Herod the Great (37 B.C.E.-ca. 1 C.E.), the king of Judah.[16] This is the only Herodian structure to survive intact into modern times. (During the Mamluk period the structure was renovated, enlarged, and the inside was constructed. This was the period during with the “old town” of Hebron—i.e., the core of modern Hebron—was built.)

Another cultic structure from this same period was constructed at Elonei Mamre (Oaks of Mamre) about three kms away from the Cave of the Patriarchs structure. The careful margin hueing and size of the immense stones (the structure is preserved up to 60 feet on top of the bedrock) is very similar to Herodian structures at the temple mount at Jerusalem, and thus Herod is believed to have been behind the building of this structure as well.

Considering his investment in these Jewish holy sites, it seems likely that Herod thought of Hebron as a Jewish city, although some have argued that the site was meant for his Idumean brethren.[17] In any event, Herod’s treating the city as Jewish does not prove that the Idumean inhabitants thought of themselves as Jews. Herod was part of the Judean royal family and was “king of the Jews” so he would naturally identify with his Jewish identity. What about the average Idumean in Hebron?

Tel Hebron Excavations Reveal a Jewish City

Our excavations at Tel Hebron during 2014 and 2017 revealed a domestic and industrial quarter dated to the Second Temple Period (from the Hasmonean period until the Bar-Kokhba revolt). Among other things, two domestic houses were excavated on both sides of a street, as well as a pottery workshop, and some agricultural installations. The general impression is that the settlement reflected a Jewish rather than a pagan or Idumean community for the following reasons:

- “Pure” vessels – Chalk stone vessels were found there. These are a common identification element for Jewish sites, since they cannot become impure according to the Jewish laws of vessel purity. Only Jews used these types of vessels that were much more difficult to make, and more expensive than clay vessels.

- Large ritual baths (מקואות) – A number of Jewish ritual baths (mikvaot) were found. (See appendix)

These new archaeological finds answer the question about the inhabitants’ religious identity clearly. Whether this means that Judeans inhabited the city, that the Idumean inhabitants embraced their Jewish identities, or both, Hebron was a Jewish town during the Hasmoneans and Roman periods.

The city was destroyed in the Great Jewish Revolt then resettled until the Bar Kokhba Revolt (132–135 CE). Although it was sparsely resettled on and off until the Mamluk period, it was not to be resettled by Jews.[18]

Addendum

The Mikvaot in Tel Hebron

In the Second Temple period, a standard mikvah consisted of a small stepped pool, in which Jews immersed, often daily, or when needed, to be clean of impurities.[19] These are very common in nearly all Jewish settlements of Second Temple Judah also occurring in the vicinity of agricultural installations related to Jewish settlements.80

In Hebron, the western mikvah is a 24×14.5-foot rectangular pool carved in the natural rock, with fourteen wide and well-plastered steps leading to a small floored pool, over 10 feet deep.

The eastern mikvah, about 40 feet to the west and better preserved, had a squarer open space, 21 × 18 feet in size and over nine feet deep, with thirteen steps going down. It was connected by two large rectangular openings carved in the rock to a large closed underground natural space in the rock about 21 × 21 feet in size. Similar mikvaot with large closed spaces were found in the archaeological sites of Alon Shevut and Beer Ijda (“Sarah’s Bath”).

The reason for the double separation, which can be seen in the above pictures, is not clear. Perhaps the aim was to separate between visitors having various degrees of impurity.

Mikvahs Not Water Reservoirs

But why are these pools identified as Jewish ritual baths at all, rather than water reservoirs or other water related installations? As Ronny Reich has shown in his seminal work, the majority of the stepped pools found in Judah during the Second Temple period and later should be identified as mikvahs. Moreover, these could not have been water reservoirs, since the stairs highly reduce the pool’s capacity, and make the drawing of the water very inconvenient.

Nor do these structures fit any other function, such as wine presses or vats. There is no other explanation for the well-smoothed rounded finishing of the plastering of the walls of the pool and the stairs, other than preventing the bathers from getting hurt when descending to be immersed, naked, and often in the dark.

While, in principle the bathing could have been non-ritual as well, this is less likely since these installations appear almost exclusively during the Second Temple Period, in Judah and the Galilee, and they correlate well with the description of mikvaot in Rabbinic texts.[20]

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

June 5, 2018

|

Last Updated

November 29, 2025

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Prof. David Ben-Shlomo is an Associate Professor of Archaeology at Ariel University. He holds a Ph.D. and M.A. in archaeology from the Hebrew University and is Co-Director of the Tel Hebron and the Jordan Valley Excavation Projects. Among his many publications are “Ritual Baths from the Second Temple Period at Hebron” (Judea and Samaria Resarch Studies), “Hebron: Still Jewish in Second Temple Times” (BAR), and Tel Hebron Excavations: Final Report (with Emanuel Eisenberg).

Essays on Related Topics: