Edit article

Edit articleSeries

The Astragali of Abel Beth Maacah

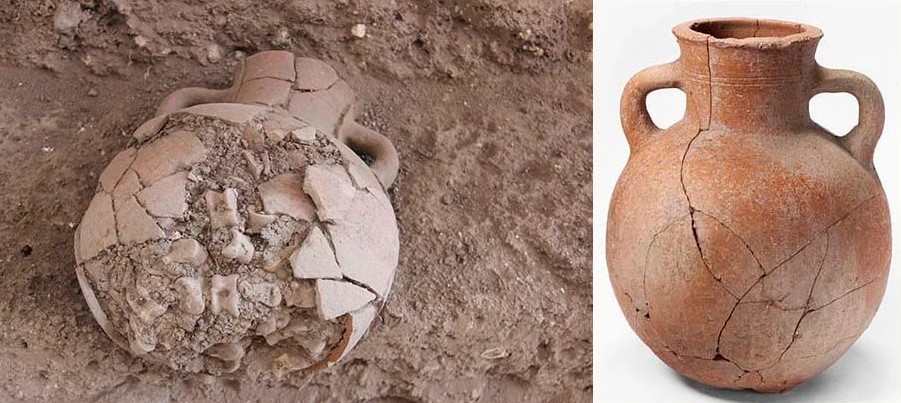

A sample of worked sheep/goat astragali from the Abel Beth Maacah hoard, with natural perforations in the central depression of the bones’ dorsal side (photo by author).

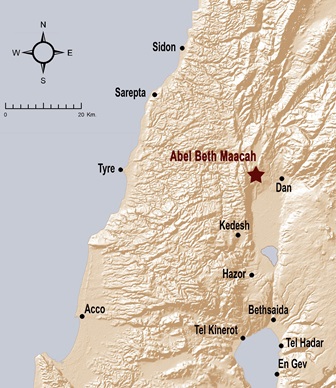

The city of Abel Beth Maacah, on the northern border of Israel, appears in the conquest itineraries of the 9th century B.C.E. Aramaean king Ben Hadad (1 Kgs 15:20) and of the later Neo-Assyrian king Tiglath-pilesar III in 732 B.C.E. (2 Kgs 15:29). The only narrative in which the city features is when a conflict erupts between the men of Israel and Judah, and a Benjaminite named Sheba, the son of Bichri, attempts to lead Israel in a rebellion against King David (2 Sam 20:1–2). David quickly calls up his army to capture Sheba before he can establish himself in the fortified cities of Israel (v. 6), and Sheba flees:

שׁמואל ב כ:יד וַיַּעֲבֹר בְּכָל שִׁבְטֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל אָבֵלָה וּבֵית מַעֲכָה וְכָל הַבֵּרִים וַיִּקָּלֲהוּ וַיָּבֹאוּ אַף אַחֲרָיו.

2 Sam 20:14 Sheba passed through all the tribes of Israel to Abel of Beth-maacah, and all the Bichrites assembled and followed him inside.[1]

David’s forces, led by Joab, prepare to attack the city to capture Sheba, but a wise woman of the city, who appears to function as a civic, if not cultic, leader, offers a “peaceful” solution: the people will throw Sheba’s head over the wall to induce Joab to withdraw his army from the city (vv. 21–22).

Before making this offer, however, the wise woman attempts to shame or frighten Joab into giving up the attack by reminding him of Abel Beth Maacah’s reputation:

שׁמואל ב כ:יח וַתֹּאמֶר לֵאמֹר דַּבֵּר יְדַבְּרוּ בָרִאשֹׁנָה לֵאמֹר שָׁאֹל יְשָׁאֲלוּ בְּאָבֵל וְכֵן הֵתַמּוּ. כ:יט אָנֹכִי שְׁלֻמֵי אֱמוּנֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל אַתָּה מְבַקֵּשׁ לְהָמִית עִיר וְאֵם בְּיִשְׂרָאֵל לָמָּה תְבַלַּע נַחֲלַת יְ־הוָה.

2 Sam 20:18 Then she said, “They used to say in the old days, ‘Let them inquire (shaʾol yeshaʾalu) at Abel,’ and so they would settle. 20:19 I am one of those who are peaceable and faithful in Israel; you seek to destroy a city that is a mother in Israel; why will you swallow up the heritage of YHWH?”

Some commentators explain that Abel Beth Maacah was known as a place to seek wise judgments.[2] The Septuagint version of this verse, however, pairs Abel with the nearby city of Dan, a known cult center—i.e., “make inquiry in Abel and in Dan”[3]—which could indicate that Abel Beth Maacah’s reputation as a place for resolving inquiries was related to cultic activity, perhaps even divination.[4] Indeed, a recent archaeological discovery at the site of Abel Beth Maacah may offer some insight into the possibility that the city could have been a center for divination.

Excavations at Tel Abel Beth Maacah

Tel Abel Beth Maacah[5]—a large (10 hectare) site in the Hula Valley, 6.5 km west of Tel Dan and just south of the modern-day border between Israel and Lebanon—was already occupied in the 3rd millennium B.C.E. By the 18th–17th centuries B.C.E., it had developed into a large and important fortified city.[6] From the 12th to the 9th centuries B.C.E., i.e., during the pre-monarchic period of Israelite settlement through the early monarchic period, it was a major regional urban center.

Among the evidence of cultic activity found at the site is a late Iron Age I (10th century B.C.E.) stratum that features a large, well-constructed building with a courtyard containing many cultic objects and furnishings and ritual-related items, including a ceramic cult stand, a stone offering table, benches, a large matzebah (standing stone),[7] a deer antler, a goat horn, and a double sink-like basin with a drain.[8]

Directly above and just a few meters west of this structure lies a large public venue from the subsequent Iron Age IIA period (ca. 10th–9th centuries B.C.E.). There, on a small, elevated podium that was located above a stone pavement, researchers discovered a small two-handled amphora containing 406 astragali.[9]

What Are Astragali?

An astragalus[10] (often called a “knucklebone”) is a small bone located in the ankle joint of the two hind legs of mammals—thus, two per animal. Those of sheep and goats, and slightly bigger ones from deer, are small enough to be easily held and manipulated in the hand. They are durable, can easily be worked, and depending on the species, the shape is somewhat cube like.

The bones at Tel Abel Beth Maacah were from adult animals: 402 were from sheep and goats and four were from deer. There was a slight preference overall for astragali from the animals’ right side. The majority of the goat astragali belonged to females.

Two hundred eleven of the bones had been modified: many with cutmarks, 42 with artificially flattened surfaces (to make the rounded and protruding sides more cube-shaped), 12 with drill holes and one with iron inserted into it. These signs indicate the astragali may have been used in a variety of ways—as tools, weights, dice, or perhaps even as jewelry or amulets—by multiple individuals before they were deposited in the amphora. A large number of the astragali also had natural perforations in the general location where drill holes were made (perhaps important as signs in divination).

Astragali in the Ancient World

The collection, use, and modification of astragali is a common cross-cultural phenomenon that has persisted for millennia up until the modern period, from the ancient Near East, the Aegean, Mesopotamia, Europe, Africa, central Asia and the Americas.[11] Many of the types of modifications found on the Abel Beth Maacah astragali appear on astragali found around the globe.[12] Often found grouped together and in isolation from other animal bones, astragali have been recovered from temples, palaces, cult corners, burials, houses, and other public contexts.

Specifically in the Iron IIA period in the southern Levant (10th–9th centuries B.C.E.), large clusters of astragali, often with over a hundred grouped together, have been recovered from a number of Israelite/Judahite, Philistine, and Phoenician sites, deposited predominantly in cultic contexts. The location of Tel Abel Beth Maacah’s hoard fits this pattern.

Astragali and their Function

Beyond the uses of individual astragali—as tools, weights, jewelry, etc.—Greek sources suggest astragali hoards served two primary functions.

Games – Herodotus (5th century B.C.E.) describes astragali being used in games as dice (History I, 94).

Divination – Pausanias (2nd century C.E.) describes astragali being used in divination. The one who is inquiring takes four astragali (from a much larger collection) and throws them onto a surface in front of a statue of Heracles. A tablet, serving as a guidebook, was used to explain the outcome of how the astragali were thrown; the different possible outcomes were divine messages (Pausanias VII: 25.1).

The fact that astragali were used for both games and divination makes sense in the context of the classical world, in which destinies were determined by deified Fates (Moira). Fate, therefore, whether in divinatory practices or in games, was in the hands of the divine.[13]

Mesopotamian Astragali

The Akkadian term for astragalus, kiṣallu (in Sumerian, ZI.IN.GI), appears in the same contexts in Akkadian texts.[14] In the game known as “The Royal Game of Ur,” two astragali of different sizes were used as dice in order to determine the moves available to the game player, similar to Herodotus’s description.

Astragali were also apparently important in the divinatory practice known as extispicy, i.e., the reading of omens from sacrificial animals’ internal organs.[15] A nearly 4,000-year-old Old Babylonian tablet (YOS 10 47) describing examination of various body parts of the sacrificed sheep—e.g., eyes, ears, mouth, tongue, jaw, teeth, nose, blood and down to the hoof and tail—includes four omens that deal with inspecting the animal’s astragali:

- If the right ankle bone (kiṣalum) is perforated, the client’s wife will become a prostitute.

- If the left ankle bone is perforated, you will take the treasure of your enemy.

- If an extra bone is present in the right ankle, the king’s heir will seize the throne.

- If an extra bone is present in the left ankle, a person with no right to the throne will seize the throne.[16]

Thus, anomalies such as perforations or extra bones were understood as portending favorable or unfavorable outcomes. The natural perforations noted above that were found on the Abel Beth Maacah could have possibly related to these practices.

Extispicy in the Bible?

The Bible does not mention astragali by name, but extispicy and divination were known to the biblical authors. Indeed, its imagery seems to lie behind Jeremiah’s description of himself as a sacrificial lamb whose organs YHWH inspects:

ירמיה יא:יט וַאֲנִי כְּכֶבֶשׂ אַלּוּף יוּבַל לִטְבוֹחַ וְלֹא יָדַעְתִּי כִּי עָלַי חָשְׁבוּ מַחֲשָׁבוֹת נַשְׁחִיתָה עֵץ בְּלַחְמוֹ וְנִכְרְתֶנּוּ מֵאֶרֶץ חַיִּים וּשְׁמוֹ לֹא יִזָּכֵר עוֹד. ירמיה יא:כ וַי־הוָה צְבָאוֹת שֹׁפֵט צֶדֶק בֹּחֵן כְּלָיוֹת וָלֵב אֶרְאֶה נִקְמָתְךָ מֵהֶם כִּי אֵלֶיךָ גִּלִּיתִי אֶת רִיבִי.

Jer 11:19 But I was like a gentle lamb led to the slaughter. And I did not know it was against me that they devised schemes, saying, “Let us destroy the tree with its fruit; let us cut him off from the land of the living, so that his name will no longer be remembered!” 11:20 But you, O YHWH of hosts, who judge righteously, who inspects the kidneys and the heart (bochen kelayot va-lev), let me see your retribution upon them, for to you I have committed my cause.

In the ancient Near East, a person’s kidneys and heart were thought to house their innermost thoughts and emotions.[17] Thus, the phrase בֹּחֵן כְּלָיוֹת וָלֵב (bochen kelayot va-leb) is traditionally translated as “who inspects thoughts and the mind.” It seems apparent, however, that a knowledge of extispicy lies in the background of this potent and poetic passage.

In addition, Ezekiel clearly describes the Babylonian king practicing extispicy (and other forms of divination):

יחזקאל כא:כו כִּי עָמַד מֶלֶךְ בָּבֶל אֶל אֵם הַדֶּרֶךְ בְּרֹאשׁ שְׁנֵי הַדְּרָכִים לִקְסָם קָסֶם קִלְקַל בַּחִצִּים שָׁאַל בַּתְּרָפִים רָאָה בַּכָּבֵד.

Ezek 21:26 [NRSVue 21:21] For the king of Babylon stands at the parting of the way, at the fork in the two roads, to use divination; he shakes the arrows; he consults the teraphim; he inspects the liver.

The techniques of shaking the arrows, which presumably involves casting or selecting them from the quiver like lots, and consulting teraphim,[18] which were figurines used in divination, are not mentioned in Babylonian texts, but examination of the liver of a sacrificed animal is well-documented.[19]

Finally, Leviticus’s requirement to immediately remove and burn a sacrificed animal’s internal organs (3:3–5) would have prevented their use in extispicy.[20]

Was Divination Practiced at Abel Beth Maacah?

While research at Abel Beth Maacah continues, it seems that the large hoard of astragali found at Abel Beth Maacah could very well have served as a conduit for performing divination. Whether the bones were used in extispicy and checked for perforations, or were meant to be cast, as in Pausanias’s description, is unclear. Perhaps a combination of the two practices occurred, in which the amphora—a closed vessel with a narrow neck—was shaken and turned upside down to allow one or a small number of astragali to come out, and whether or not the bone had a perforation would have determined the answer to the diviner’s inquiry.

On a final note, unlike internal organs, bones survive unchanged for a very long time. Astragali could thus be both interpreted immediately following the slaughter of an animal—i.e., for extispicy—and subsequently transformed into devices that bore continued oracular portent. Indeed, astragali are durable, small, and easy to handle, store and move. It is likely these properties that allowed for their collection and oracular use over long periods of time and that enabled them to become such important and popular items of the Iron Age.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

April 27, 2023

|

Last Updated

January 4, 2026

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Dr. Matthew Susnow is a lecturer and postdoctoral researcher in the Hebrew University of Jerusalem’s Department of Archaeology. He holds a Ph.D. in archaeology from the University of Haifa (2019) and additionally has an M.A. from the Divinity School at the University of Chicago (2011). He is the author of The Practice of Canaanite Cult: The Middle and Late Bronze Ages (Zaphon, 2021). His research focuses on various aspects of archaeology of the Bronze and Iron Age southern Levant, especially religion and ritual. Matt is also a staff member of the Tel Abel Beth Maacah expedition.

Essays on Related Topics: