Edit article

Edit articleSeries

Why Is David and Goliath’s Story 40% Longer in the MT Than in the LXX?

David by Bernini, 1623-1624, Villa Borghese, Rome. Wikimedia

The Septuagint (LXX) is missing about 40–45% of the Masoretic Text (MT) of the story of David’s triumph over Goliath and his subsequent rise to fame (1 Samuel 17–18).[1] Both the MT and LXX begin with the Philistines and Israelites gathering their armies for battle at the Valley of Elah (17:1–3). Goliath, a giant warrior,[2] challenges the Israelites to pick a champion to duel with him:

שׁמואל א יז:ח וַיַּעֲמֹד וַיִּקְרָא אֶל מַעַרְכֹת יִשְׂרָאֵל וַיֹּאמֶר לָהֶם לָמָּה תֵצְאוּ לַעֲרֹךְ מִלְחָמָה הֲלוֹא אָנֹכִי הַפְּלִשְׁתִּי וְאַתֶּם עֲבָדִים לְשָׁאוּל בְּרוּ לָכֶם אִישׁ וְיֵרֵד אֵלָי. יז:ט אִם יוּכַל לְהִלָּחֵם אִתִּי וְהִכָּנִי וְהָיִינוּ לָכֶם לַעֲבָדִים וְאִם אֲנִי אוּכַל לוֹ וְהִכִּיתִיו וִהְיִיתֶם לָנוּ לַעֲבָדִים וַעֲבַדְתֶּם אֹתָנוּ.

1 Sam 17:8 He stood and shouted to the ranks of Israel, “Why have you come out to draw up for battle? Am I not a Philistine, and are you not servants of Saul? Choose a man for yourselves, and let him come down to me. 17:9 If he is able to fight with me and kill me, then we will be your servants, but if I prevail against him and kill him, then you shall be our servants and serve us.”[3]

MT: David is a Shepherd Boy

David, who in the previous chapter was brought into Saul’s court as a musician tasked with soothing the tormented king’s spirit (1 Sam 16:14–23), is in the MT version re-introduced as a shepherd boy, sent by his father to visit the Israelite army, bringing supplies and well-wishes for his three eldest brothers, who are soldiers, and for their superiors:

שׁמואל א יז:כ וַיַּשְׁכֵּם דָּוִד בַּבֹּקֶר וַיִּטֹּשׁ אֶת הַצֹּאן עַל שֹׁמֵר וַיִּשָּׂא וַיֵּלֶךְ כַּאֲשֶׁר צִוָּהוּ יִשָׁי וַיָּבֹא הַמַּעְגָּלָה וְהַחַיִל הַיֹּצֵא אֶל הַמַּעֲרָכָה וְהֵרֵעוּ בַּמִּלְחָמָה.

1 Sam 17:20 David rose early in the morning, left the sheep with a keeper, took the provisions, and went as Jesse had commanded him. He came to the encampment as the army was going forth to the battle line, shouting the war cry.

From the battle lines, David hears Goliath’s taunts and wonders what the reward will be for defeating the Philistine:

שׁמואל א יז:כו וַיֹּאמֶר דָּוִד אֶל הָאֲנָשִׁים הָעֹמְדִים עִמּוֹ לֵאמֹר מַה יֵּעָשֶׂה לָאִישׁ אֲשֶׁר יַכֶּה אֶת הַפְּלִשְׁתִּי הַלָּז וְהֵסִיר חֶרְפָּה מֵעַל יִשְׂרָאֵל כִּי מִי הַפְּלִשְׁתִּי הֶעָרֵל הַזֶּה כִּי חֵרֵף מַעַרְכוֹת אֱלֹהִים חַיִּים.

1 Sam 17:26 David said to the men who stood by him, “What shall be done for the man who kills this Philistine and takes away the reproach from Israel? For who is this uncircumcised Philistine that he should defy the armies of the living God?”

These scenes of David as the shepherd boy are absent in the LXX, which continues from the previous chapter with David already a member of Saul’s entourage.

In a verse found in both the MT and LXX, the Israelites react with fear and dismay to Goliath’s taunts, and David bravely volunteers to fight the imposing warrior:

שׁמואל א יז:לב וַיֹּאמֶר דָּוִד אֶל שָׁאוּל אַל יִפֹּל לֵב אָדָם עָלָיו עַבְדְּךָ יֵלֵךְ וְנִלְחַם עִם הַפְּלִשְׁתִּי הַזֶּה.

1 Sam 17:32 David said to Saul, “Let no one’s heart fail because of him; your servant will go and fight with this Philistine.”

Saul at first rejects David’s offer: David is just a boy, and the Philistine man has been a warrior since his youth (17:32–33). David’s anecdotes of his triumphs against wild animals during his time as a shepherd convince Saul, and he attempts to equip David with his own armor. When that proves too cumbersome, however, David heads out with only his staff and his sling (vv. 34–39). After exchanging taunts with Goliath (vv. 42–48a), David kills him with his slingshot:

שׁמואל א יז:מט וַיִּשְׁלַח דָּוִד אֶת יָדוֹ אֶל הַכֶּלִי וַיִּקַּח מִשָּׁם אֶבֶן וַיְקַלַּע וַיַּךְ אֶת הַפְּלִשְׁתִּי אֶל מִצְחוֹ וַתִּטְבַּע הָאֶבֶן בְּמִצְחוֹ וַיִּפֹּל עַל פָּנָיו אָרְצָה.

1 Sam 17:49 David put his hand in his bag, took out a stone, slung it, and struck the Philistine on his forehead; the stone sank into his forehead, and he fell face down on the ground.

The emboldened Israelite army routs the Philistines (vv. 51–54).

MT: Saul Does Not Know David

The scene in the MT (not in the LXX) then shifts back in time to the beginning of the battle and focuses on Saul, who does not appear to know David:

שׁמואל א יז:נה וְכִרְאוֹת שָׁאוּל אֶת דָּוִד יֹצֵא לִקְרַאת הַפְּלִשְׁתִּי אָמַר אֶל אַבְנֵר שַׂר הַצָּבָא בֶּן מִי זֶה הַנַּעַר אַבְנֵר וַיֹּאמֶר אַבְנֵר חֵי נַפְשְׁךָ הַמֶּלֶךְ אִם יָדָעְתִּי.

1 Sam 17:55 When Saul saw David go out against the Philistine, he said to Abner, the commander of the army, “Abner, whose son is this young man?” Abner said, “As your soul lives, O king, I do not know.”

After David has killed the Philistine warrior, Abner brings him to meet Saul (vv. 56–58). Saul’s son Jonathan quickly befriends David, and the young shepherd becomes part of Saul’s army (18:1, 3–5).

In both the MT and LXX, David’s success in battle, and the Israelite women’s recognition of it, perturbs Saul (18:6–8, 12a). Though David is useful to Saul and becomes a beloved commander in the army (vv. 13–16), Saul attempts to kill David.

MT: Saul Offers David His Daughter Merab

In a scene that is present only in the MT, Saul, hoping that David will die in battle, then offers his daughter Merab to David in marriage in exchange for David’s agreement to fight the Philistines:

שׁמואל א יח:יז וַיֹּאמֶר שָׁאוּל אֶל דָּוִד הִנֵּה בִתִּי הַגְּדוֹלָה מֵרַב אֹתָהּ אֶתֶּן לְךָ לְאִשָּׁה אַךְ הֱיֵה לִּי לְבֶן חַיִל וְהִלָּחֵם מִלְחֲמוֹת יְ־הוָה וְשָׁאוּל אָמַר אַל תְּהִי יָדִי בּוֹ וּתְהִי בוֹ יַד פְּלִשְׁתִּים.

1 Sam 18:17 Then Saul said to David, “Here is my elder daughter Merab; I will give her to you as a wife; only be valiant for me and fight YHWH’s battles.” For Saul thought, “I will not raise a hand against him; let the Philistines deal with him.”

Merab, however, is given to another before the wedding can happen (v. 19).

Both the MT and LXX also include a similar scene in which Saul offers his daughter Michal to David:

שׁמואל א יח:כה וַיֹּאמֶר שָׁאוּל כֹּה תֹאמְרוּ לְדָוִד אֵין חֵפֶץ לַמֶּלֶךְ בְּמֹהַר כִּי בְּמֵאָה עָרְלוֹת פְּלִשְׁתִּים לְהִנָּקֵם בְּאֹיְבֵי הַמֶּלֶךְ וְשָׁאוּל חָשַׁב לְהַפִּיל אֶת דָּוִד בְּיַד פְּלִשְׁתִּים.

1 Sam 18:25 Then Saul said, “Thus shall you say to David, ‘The king desires no marriage present except a hundred foreskins of the Philistines, that he may be avenged on the king’s enemies.’” Now Saul planned to make David fall by the hand of the Philistines.

Yet, here as well, David does not fall in battle, and the narrative in the MT and LXX ends with Saul’s fear and David’s fame growing.

Additions to the Story in the MT

In sum, the following scenes and characters in MT are not present in the LXX:

- The lengthy introduction of David as a shepherd boy (17:12–31)

- Saul and his general, Abner, inquiring about David’s name (17:55–58)

- Jonathan making a covenant with David (18:1–5)

- Saul offering his daughter Merab to David in marriage (18:17–19)

Explaining the differences between the MT and LXX is one of the best-known and complex problems of biblical textual criticism.

The Addition Hypothesis

The “Addition Hypothesis” posits that the shorter LXX account represents an older version of the narrative, Version 1,[4] while the MT includes material that was added later, long after the bulk of the book of Samuel had come together.[5] The most common explanation for the MT-“pluses” is that they comprise an old, originally separate and complete, David tradition, Version 2, that was edited into MT-Samuel during the Persian period.[6] In sum, the LXX contains only Version 1 of the narrative, while the MT combines Versions 1 and 2.

Version 1 (the LXX and MT): David, a Servant of Saul

Version 1 begins with David already part of the king’s entourage, as he was brought into Saul’s court in the previous chapter (1 Sam 16:14–23). After hearing the Philistine champion’s taunts (17:1–11), David volunteers to fight (17:32). Saul is unable to either dissuade David or arm him, and David faces and kills Goliath with only a sling for a weapon (vv. 33–39, 42–48a, 49, 51).

The Israelites defeat the Philistines, Saul makes David a commander in his army, and, in an attempt to arrange David’s death in battle, he offers his daughter Michal’s hand in marriage if David will attack the Philistines (17:52–54, 18:13–16, 20–21a, 22–26a). Version 1 ends with a description of Saul’s growing fear of David (18:28–29a).

Version 2 (MT-pluses): David, the Shepherd

In Version 2, David is present at the battle by happenstance, sent there by his father (17:12–22). When he hears the Philistine’s taunts, he is “in the trenches,” talking with the men on the battle-lines (vv. 23–30). As the Philistine approaches, the young shepherd launches a successful surprise attack, killing the Philistine with his sling (vv. 41, 48b, 50).

Seeing this, Saul asks who David is, and Abner then brings David to meet Saul (vv. 55–58). Saul’s son Jonathan quickly befriends David, and the young shepherd becomes part of Saul’s army (18:1, 3–5). Saul also offers his daughter Merab to David in marriage, but she is given to another before the wedding can happen (vv. 17–19). Version 2 seems to end with David being highly regarded within Saul’s court (v. 30).

Aligning the Two Versions

Several verses found only in the MT are not part of the original story, but in this theory are redactional additions designed to connect the two originally distinct versions of the narrative. For example, one verse resolves David’s roles as court musician (Version 1) and shepherd (Version 2) by stating that David split his time between his home and Saul’s camp:[7]

שׁמואל א יז:טו וְדָוִד הֹלֵךְ וָשָׁב מֵעַל שָׁאוּל לִרְעוֹת אֶת צֹאן אָבִיו בֵּית לָחֶם.

1 Sam 17:15 But David went back and forth from Saul to feed his father’s sheep at Bethlehem.

A subsequent verse, also a later addition, describes Saul permanently taking David into his court (18:2).

Another problem in aligning the two versions is that David departs for his battle with Goliath from different places in each narrative:

In Version 2, David is on the battle-lines speaking to the Israelite soldiers (17:23–30).

In Version 1, David is with Saul, and they have an extended exchange about David’s offer to fight (17:32–39).

To solve this problem, the editor added a verse indicating that Saul sent for David after hearing what David had been saying on the battle-lines:

שׁמואל א יז:לא וַיְּשָּׁמְעוּ הַדְּבָרִים אֲשֶׁר דִּבֶּר דָּוִד וַיַּגִּדוּ לִפְנֵי שָׁאוּל וַיִּקָּחֵהוּ.

1 Sam 17:31 When the words that David spoke were heard, they repeated them before Saul, and he sent for him.

Several other short clauses of the MT-pluses are also redactional and serve similar purposes (e.g., 18:26b, 29b).[8]

Challenges to the Addition Hypothesis

One problem with the Addition Hypothesis is that while the LXX does not include Version 2 of the David and Goliath narrative, it subsequently appears to refer to details from it, most importantly the covenant that David and Jonathan make right after they meet, which is only found in the MT:

שׁמואל א יח:א וַיְהִי כְּכַלֹּתוֹ לְדַבֵּר אֶל שָׁאוּל וְנֶפֶשׁ יְהוֹנָתָן נִקְשְׁרָה בְּנֶפֶשׁ דָּוִד וַּיֶּאֱהָבֵוּ יְהוֹנָתָן כְּנַפְשׁוֹ.... יח:ג וַיִּכְרֹת יְהוֹנָתָן וְדָוִד בְּרִית בְּאַהֲבָתוֹ אֹתוֹ כְּנַפְשׁוֹ. יח:ד וַיִּתְפַּשֵּׁט יְהוֹנָתָן אֶת הַמְּעִיל אֲשֶׁר עָלָיו וַיִּתְּנֵהוּ לְדָוִד וּמַדָּיו וְעַד חַרְבּוֹ וְעַד קַשְׁתּוֹ וְעַד חֲגֹרוֹ.

1 Sam 18:1 When David had finished speaking to Saul, the soul of Jonathan was bound to the soul of David, and Jonathan loved him as his own soul…. 18:3 Then Jonathan made a covenant with David because he loved him as his own soul. 18:4 Jonathan stripped himself of the robe that he was wearing and gave it to David and his armor and even his sword and his bow and his belt.[9]

Later, the LXX (consistent with the MT) describes an oath made between the two men as being taken “again,” seemingly referring back to that original covenant in Version 2:

LXX 1 Sam 20:17 And Ionathan added again to swear to Dauid, for he loved the soul of one loving him.[10]

שׁמואל א כ:יז וַיּוֹסֶף יְהוֹנָתָן לְהַשְׁבִּיעַ אֶת דָּוִד בְּאַהֲבָתוֹ אֹתוֹ כִּי אַהֲבַת נַפְשׁוֹ אֲהֵבוֹ.

MT 1 Sam 20:17 Jonathan made David swear again by his love for him, for he loved him as he loved his own life.

In a subsequent narrative, King David executes a number of Saul’s descendants at YHWH’s command (2 Sam 21). The Lucianic LXX recension (LXXL), includes among those killed “the sons of Merab…whom she bore to Adriel” (v. 8).[11] Adriel is not otherwise mentioned in Samuel in the LXX. In the MT, however, he does appear after Saul initially offers Merab to David:

שׁמואל א יח:יט וַיְהִי בְּעֵת תֵּת אֶת מֵרַב בַּת שָׁאוּל לְדָוִד וְהִיא נִתְּנָה לְעַדְרִיאֵל הַמְּחֹלָתִי לְאִשָּׁה.

1 Sam 18:19 But at the time when Saul’s daughter Merab should have been given to David, she was given to Adriel the Meholathite as a wife.

If the scene of Merab’s marriage to Adriel is a later addition to the MT, how would the LXX know to refer to it?

The Omission Hypothesis

These issues of narrative continuity—of the LXX referring to narrative details that are present in the MT, but not present in its own version of the David and Goliath narrative—are often cited to justify an alternative to the Addition Hypothesis: the “Omission Hypothesis,” which proposes that the MT represents the older text,[12] and that the LXX version was created when an editor omitted those portions of the MT that were thought to be problematic in some way. Specifically, the translator of the Septuagint found parts of the story to be redundant or superfluous. In one version of this theory, the redundant portions of the MT arose because an earlier editor had combined multiple accounts, and the Septuagintal translator was simply “fixing” the overly-full story.[13]

But in another major line of argumentation, the MT works better as a folktale than does the shorter LXX version. On this account, the fuller MT text is viewed to be the archaic original precisely because of the twisting and turning plot, the multiple points of view offered by the narrator, and the intrigue involving the offer that David should marry the king’s daughter.[14]

Challenges to the Omission Hypothesis

The Omission Hypothesis offers an explanation for the literary continuities between the MT’s Version 2 material and later portions of LXX-Samuel. It has difficulty, however, explaining the evidence that the passages that the LXX editor excised from the David and Goliath narrative comprise a complete story of David’s battle with Goliath and its aftermath, along with all of the verses that serve to connect the two versions.[15] How could an editor, no matter how careful, have removed this material with such precision?

A New Way Forward: The Corruption-Replacement Hypothesis

Consideration of the material aspects of ancient texts suggests a new explanation of the evidence: that the LXX tradition developed from the repair of a damaged scroll. Ancient scrolls were subject to wear and tear over time, and they occasionally required repairs to restore damaged text. In such cases, a scribe would stitch the replacement text to the original.

Replacement Sheets at Qumran

For example, manuscripts at Qumran show evidence that they have been patched:[16]

- A fragment of a manuscript of Jubilees (4Q216 = 4QJubileesa) preserves portions of two different sheets, along with the stitching holding them together.[17] Molly Zahn notes: “The two sheets are written in two different hands, the first dating to the mid-first century B.C.E. and the second to approximately 125–100 B.C.E. That is, the writing on the second sheet is considerably older than that on the first sheet.”[18]

- A sheet that contained an older copy of the Temple Scroll (11Q19) has had newer sheet added to its right side, patching the text. Again there is a clear shift in both the material qualities of the parchment and the handwriting associated with each between the two sheets.[19]

Patching may also explain the significant differences between the LXX and MT versions of the David and Goliath narrative.

Version 1 in the LXX as a Replacement Text

Scrolls did not normally reach the lengths required to contain the entire text of most biblical books. Indeed, the book of Samuel was likely too large to fit on a single scroll.[20] The Corruption-Replacement Hypothesis posits that in a “parent-manuscript” of the LXX, the first scroll of the book of Samuel ended with a version of 1 Samuel 17–18 similar to the MT.

The final narrative contained in this shorter scroll would therefore relay the full story of how David defeated a Philistine giant and came into Saul’s court, married Saul’s daughter, befriended Saul’s son, the crown prince, and proved himself on the field of battle, gaining renown (18:30). It was in the following companion scroll that an entirely different narrative was told, i.e., how David was chased from Saul’s house and forced to live as an outlaw until he ascended to the throne.

At some point, the end of the first scroll was damaged, but instead of replacing chapters 17–18 with the MT-like text of Samuel, a scribe used a manuscript containing only Version 1 of the narrative.[21] This solution assumes that at that point in time, there were still manuscripts in existence that contained only Version 1, and the scribe copied from one of these to repair the damaged LXX scroll. The scribe may not even have realized that this document was shorter than the text that he was repairing.[22]

Where the Patch Could Have Been Added

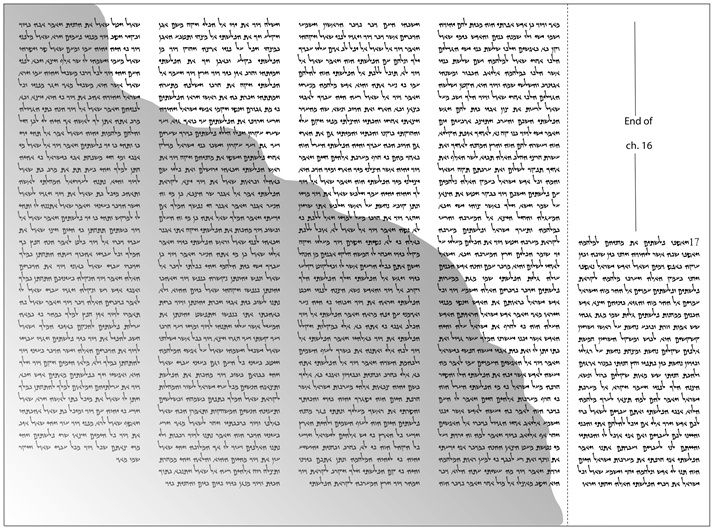

The repair of the scroll did not necessarily begin right where the MT deviates from the LXX (in 17:12). The patch could have begun anywhere between 1 Samuel 16:14–17:11, as this material all comes from the same author.[23] The shaded portion of the text in the following schematic figure represents the damage to the scroll. The dotted line between the first two columns on the right represents the margin where the textual specialist could have cut off the damaged section of the scroll and attached the new piece.

Fig. 1: Heuristic representation of damage to a Hebrew parent manuscript of LXX at 1 Samuel 17–18. This figure uses the font 1QM, courtesy of the Dead Sea Scrolls Project, University of Haifa; design: Einat Tamir ( accessed Feb. 2, 2023). Image © J. M. Hutton, with assistance from Nathaniel E. Greene.

Fig. 1: Heuristic representation of damage to a Hebrew parent manuscript of LXX at 1 Samuel 17–18. This figure uses the font 1QM, courtesy of the Dead Sea Scrolls Project, University of Haifa; design: Einat Tamir ( accessed Feb. 2, 2023). Image © J. M. Hutton, with assistance from Nathaniel E. Greene.

The reconstruction presented here is admittedly conjectural.[24] Yet, it attempts to take seriously the material witnesses to scribal culture that archaeologists have recovered from the Dead Sea basin alongside other modes of performing text-historical reconstruction. If this hypothesis is correct, it provides additional evidence for two longstanding ideas.

First, it would offer, through indirect evidence, another example of a text that had undergone damage and subsequent repair. Second, it would constitute further evidence that alternative textual traditions existed alongside more popular or “authoritative” ones in antiquity.[25] In this case, the alternative tradition preserved one of the original sources of the tradition that became authoritative in the form of 1–2 Samuel as we know it.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

July 4, 2023

|

Last Updated

March 21, 2025

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Prof. Jeremy Hutton is Professor of Classical Hebrew Language and Biblical Literature in the University of Wisconsin–Madison’s Department of Classical and Ancient Near Eastern Studies. He holds a B.A. in Philosophy and Theology from the University of Notre Dame, and an A.M. and Ph.D. in Hebrew Bible and Semitic Philology from Harvard University. He is the author of The Transjordanian Palimpsest: The Overwritten Texts of Personal Exile and Transformation in the Deuteronomistic History (2009) and co-author (with C. L. Crouch) of Translating Empire: Tell Fekheriyeh, Deuteronomy, and the Akkadian Treaty Tradition (2019), as well as the author or co-author of dozens of articles. He is currently working on projects in several sub-fields of Hebrew Bible and Northwest Semitics, including the composition and reception history of the book of Samuel; translation in antiquity; Palmyrene Aramaic epigraphy; the roles of priests and Levites in Iron Age Israel; and cognitive linguistic approaches to Hebrew semantics.

Essays on Related Topics: