Edit article

Edit articleSeries

YHWH: The God that Is vs. the God that Becomes

Burning bush sculpture by David Palombo (1966) at the entrance of the Knesset, Jerusalem

The Multiple Names of God

The Bible has multiple names for God. Jean Astruc (18th cent.), one of the founding fathers of biblical criticism, used the pattern of divine names YHWH and Elohim in Genesis and early Exodus to explain the contradictory accounts in the Bible. He suggested that they derived from two different sources that made use of one or the other of these names for God.[1] This insight laid the groundwork for what eventually matured into the Documentary Hypothesis.

The multiplicity of divine names—and not just YHWH and Elohim—are equally crucial for the development of Jewish theology, or, more correctly, theologies. After listing all the names used for God in his classic study of them, the Jewish theologian Arthur Marmorstein (1882-1946), who was both a yeshiva trained rabbi and a professor at Jews College, observed:

Here a wealthy sanctuary of the most treasured religious ideas and doctrines is opened to us, which invites entrance to all who want to come nearer to God. Nowhere is the creative genius of the pious scribes more at its best than in this long list.[2]

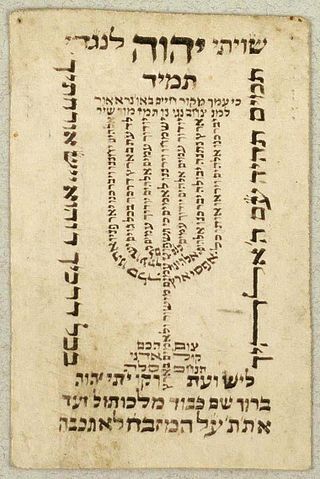

The canonical texts subtly shift between such epithets as Elohim, El, Adonai, Shaddai, Zevaotand, of course, the Tetragrammaton, YHWH, the four letter name that was paradoxically termed, the unpronounceable, “articulated name” (shem hameforash).[3] Whatever sense this phrase actually conveys, so sacrosanct was it considered that its explicit vocalization became taboo.[4]

Lost in Translation

Readers familiar with the Bible solely through translation, even the most devoted ones, remain unaware of this critical dimension in the biblical and rabbinic biography of God. Years in the classroom teaching the Hebrew Bible to undergraduates with no background in Hebrew have taught me this first hand. Distinctions between the different names are often blurred by their indiscriminate renderings as “God,” “LORD,” or “Lord.”[5]

Jewish Theology vs. Biblical Theology

Historical criticism is immensely important for reconstructing the complex formation of an ancient text, or even for excavating modes of divine encounters in an ancient Near Eastern context. From a historical-critical perspective, the different names of God may signal the disjointed fragments of a layered text offering clues to the disentangling a multi-authorial composition spanning many centuries.

Even so, as one prominent Jesuit scholar of the Old Testament put it, historical-critical research may only provide a “foundation of sand” for understanding any theological development.[6] If such is the case for Christian theology, it is even more apropos the evolution of Jewish thought. Since the Hebrew Bible became canonized, it has been read and intricately reread starting with the Second Temple works such as Jubilees, and continuing with the rabbinic sages in antiquity, and on. The Bible, on its own terms, therefore is a rich source of Jewish theology, but cannot be divorced from its long ensuing history of interpretation.

Of late, contemporary Jewish biblical scholars have expressed much greater interest in biblical theology.[7] However, Jewish theology, i.e., the approach of rabbinic Judaism throughout its long history, as opposed to biblical theology, i.e., the attempt to understand the Bible in its original context, emerges out of encountering the text holistically in its final redacted version. Approached this way, the alternating divine names offer clues, not to authorial construction, but to deific construction, leading to wholly different notions of a deity.

Theological Approaches to Understanding the Divine Names

For some, the names coalesce to produce austere philosophical abstractions of an immutable characterless God, lacking anything related to personhood. For others, they individually manifest different attributes that parallel human characteristics such as compassion and rigor. And for yet others, they indicate the elusiveness, the dynamism, of a God evolving, in tandem and reciprocally, with his creation and his creatures.

All of the Jewish intellectual traditions—rabbinic/midrashic, rationalist/ philosophical, and kabbalistic/mystical[8] — have profoundly engaged these different appellations, exploring and determining their meanings, significations, and precise roles within the diverse biblical contexts in which they appear.[9]

Maimonides – Names Derived from Actions

Moses Maimonides or Rambam (1138-1204), Judaism’s chief exponent of the rationalist tradition, holds that all divine names, except the Tetragrammaton, “correspond to the actions existing in the world,”[10] which reflect the different characteristic the name designates. As he states, they “derive from actions.”[11] Simply put, since a fundamental premise of his negative theology is that God possesses no attributes, the referent of these names is not God but rather phenomena in the natural world. Since nature is linked to God by virtue of it being His creation, a particular name or attribute is then semiotically reoriented toward God in His capacity as the remotest cause in the long chain of natural causation.

These names, in one sense, play a practical role for the sake of providing some linguistic referent for the purposes of religious worship such as prayer. Yet, if taken literally, they are simply false, and it is done at the cost of philosophical coherence. (On Maimonides’s understanding of the Tetragrammaton, see below.)

Nahmanides – Dimensions of God’s Dynamic Being

On the other end of the Jewish theological spectrum is Moses Nahmanides or Ramban (1194-1270), one of the most prominent medieval rabbinic exegetes and Kabbalistic expositors of the Bible. For him, God is far more reactive and personal than some remote first cause of existence, and thus the names capture different dimensions of God’s dynamic being. In fact, they are such paramount divine ciphers as to form the algorithmic keys to the Torah since it can be read in its entirety as an elongated continuous thread of divine names.[12]

In other words, the Bible only superficially records historical events, depicts human characters, and normatively regulates human conduct by mitzvot. All that comprises simply an external shell that masks an entirely different story. That story is an esoteric narrative pulsating beneath the surface that charts the life of God, via the medium of names. The transition from a solid block of names to an individuated one of discrete words is for the sake of human intelligibility. It marks a transition from “the supra-legal to the legal, from a primordial Torah to the written and oral Torah, from the invisible to the visible.”[13]

The Name YHWH

Essential to the development of all divine name theology is the name YHWH, which, occurs repeatedly throughout the book of Genesis, but is only introduced formally, in direct response to Moses’ request for it, in Exod. 3:13 at the burning bush theophany. Exod. 6:3 corroborates its unprecedented disclosure to Moses-

וָאֵרָא אֶל אַבְרָהָם אֶל יִצְחָק וְאֶל יַעֲקֹב בְּאֵל שַׁדָּי וּשְׁמִי יְהוָה לֹא נוֹדַעְתִּי לָהֶם.

I appeared to Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob as E-l Shad-dai, but I did not make Myself known to them by My name YHWH.

Although its apparent meaning is “cause to be,” it remains unclear what precisely the name means. Cognate Semitic roots inventively render alternatives ranging from “blow” (thus a storm god), to “fall” (thus the one who destroys), to “roar” (thus the god of thunder), to “passionate,” to name but a few.[14] The interminable debates regarding its meaning are so wide-ranging one scholar claims they form a separate academic discipline of “hayyaology.”[15]

Ehyeh asher Ehyeh

Whatever the historical meaning of the name, the Torah’s first communication of it to Moses includes an etymological nod towards its meaning in the seemingly tautological and seductive play on the root “to be” of ehyeh asher ehyeh (Exod. 3:14) “I will be who I will be” or “I am who I am.”

וַיֹּאמֶר אֱלֹהִים אֶל מֹשֶׁה אֶהְיֶה אֲשֶׁר אֶהְיֶה וַיֹּאמֶר כֹּה תֹאמַר לִבְנֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל אֶהְיֶה שְׁלָחַנִי אֲלֵיכֶם.

And God said to Moses, “Ehyeh-Asher-Ehyeh.” He continued, “Thus shall you say to the Israelites, ‘Ehyeh sent me to you.'” (NJPS)

This enigmatic phrase, evasively formulated in the first person imperfect form of the root “to be,” rather than the third person of the name itself, has provoked an endless stream of translations, interpretations, and scholarship, from the Septuagint, the ancient Greek translation, to the twentieth century philosopher Martin Buber, and beyond. This contentiousness itself attests to what I believe is its deliberate ambiguity and irresolvable open-endedness.[16]

Enigmatic as it may be, ehyeh asher ehyeh remains the sole overt exposition of the divine name YHWH in the entire Hebrew Bible.[17] Thus, it is also of utmost importance to comprehend the narrative context from which it emerged to become a mainstay of any Jewish theology, philosophical or otherwise.

Franz Rosenzweig considered the attempt to understand this phrase paramount for what he felt is the “task” of Jewish theology since this encounter and dialogue between Moses and God out of which the name emerges is that moment which foundationally envisages all future divine/human encounters. Rosenzweig credited Moses Mendelssohn with pioneering the “task” of understanding the full import of this inaugural encounter, of “connecting the name to the moment at which the name was revealed.”[18]

Philosophical Interpretation of YHWH: Being

Philosophically abstract conceptions of God originate with the ancient Greeks, and have influenced the development of philosophical theology through the Middle Ages to the present day. The Greek Septuagint version of ehyeh asher ehyeh as “I am the One who is” (ego eimi ho on), overwhelmingly influenced the history of biblical translation. It overshadowed all ensuing interpretation with a present tense that is amenable to Greek metaphysics and ontology of pure Being.[19] Subsequently, there emerged:

- Philo’s “the Being who Is,”[20]

- The New Testament’s “the Was, the Being, and the Is to come,”[21]

- Maimonides’ “necessary existent,”

- Aquinas’ “true being, immutable, simple self-sufficient,”

- Moses Mendelssohn’s “Eternal Being” (ewige Wesen).

These understandings take this present tense metaphysics to its logical conclusions.[22]

This seemingly innocuous grammatical inflection set the agenda for all future onto-theological notions of divine perfection in their respective religious traditions.[23] Jewish theology has consequently been torn between the perfect immutable impersonal God that is,and the personal, relational God that is not static and fixed but rather becomes.

For Maimonides, YHWH is the one name of God that signifies pure divine essence stripped of all attributes. As such it signifies a wholly abstract being unrelated to the world. In fact, it is so detached from history and humanity that Maimonides draws on a midrash which considers God and the name YHWH to have preceded the creation of the world as an endorsement of this proposition.[24]

Significance of the “God of Being” in Christianity

Despite Maimonides and the school of Jewish rationalism of which he is the leading exponent, this view of a pure unchanging perfect necessary existence, devoid of any characteristics associated with personhood, known as “Being,” was far more endemic to Christianity. All the evidence indicates it is a foreign intruder to the rabbinic tradition. Etienne Gilson best sums this up with his assertion that

Exodus lays down the principle from which henceforth the whole of Christian philosophy will be suspended… There is but one God and this God is Being, this is the cornerstone of all Christian philosophy.[25]

A recent exhaustive study of Western Christianity’s reception of the Name similarly asserts,

For some fifteen centuries from the Fathers to Leibnitz and Wolff, the God of Moses’ religion and the Being of Greek philosophy met without confusion at the heart of the Christian faith.[26]

Yet, God’s declaration ehyeh, as a form of the root “to be,” in addition to its open-endedness, does not explicitly disclose the name YHWH. It seems to be an intentional evasion of Moses’ request for a name that uniquely identifies someone or something. It thus defies the kinds of definition and classification that are the hallmarks of philosophical reasoning. Even Philo himself, the ancient pioneer of philosophical theology, admits this when he supplements the meaning of YHWH as Being with the lesson that “no name at all can properly be used of Me, to whom all existence belongs.”[27]

Mystical Interpretation of YHWH: Expressing a Relationship

While the rationalist movement attempted to purge the Bible of all its mythic dimensions, classical rabbinic thought, continuing through its midrashic genres, and on through kabbalah, actually picked up on that myth, developing, expanding, and enhancing it even further.[28]

How else can one characterize God wearing tefillin(phylacteries), accompanied by a debate that appears early on in the Talmud, as to what biblical passages are inserted in the divine tefillin compartments![29] It turns out that God’s tefillin are the mirror image of their human counterpart. Just as the latter contains the passage declaring God’s uniqueness so the former contains an analogous declaration:

Jew’s tefillin (Deut 6:4)

שְׁמַע יִשְׂרָאֵל יְ-הוָה אֱלֹהֵינוּ יְ-הוָה אֶחָד.

Hear O Israel YHWH is our God, YHWH alone (eḥad).

God’s tefillin (1 Chr 17:21)

וּמִי כְּעַמְּךָ יִשְׂרָאֵל גּוֹי אֶחָד בָּאָרֶץ…

Who is like your people Israel, a unique (eḥad) nation on the earth…

As such, YHWH conveys more of a relational being in a partnership of reciprocity with Israel. It connotes a God of endless becoming, as the imperfect I will be indicates, a deity who cannot but be elusive, continually shaped and reshaped by the respective partners with whom it establishes a relationship. Other divine names then derive naturally in this respect from the core relational name YHWH. They correlate to various dimensions of God such as compassion, mercy, or justice, which are all manifest in relationships.

As opposed to Maimonides’ detached, unaffected, necessary existence, Rashi exquisitely captures this God of relationship by fleshing out the meaning of ehyeh asher ehyeh as,

אהיה עמם בצרה זו אשר אהיה עמם בשעבוד שאר מלכיות.

I will be with them during this affliction as I will be with them during their oppression by other kingdoms.

God provides the comfort, assistance, and empathy expected of any partner in a meaningful relationship.

An Atbash (Transposed Anagram) Interpretation

Kabbalistic reinventions of ehyeh asher ehyeh, push this relational mutuality between God and human beings to striking extremes. For example, employing a traditional anagrammatic technique of transposing letters in words to create new words, in this case the last letter of the alphabet for the first (atbash), the Name becomes I will be what you will be [30] אהיה אשר תהיה.

Midrashic Interpretation of Yah – A Broken Relationship

Midrashic traditions further deepen the interdependence required by authentic relationships. For example, a partial appearance of the name YHWH such as YH (Exod. 17:16) indicates for the Rabbis a “partial” God, signifying a deity whose imperfect state of brokenness, alienation, and even exile, especially in the face of substantive evil in the world, can only be remedied by the restorative acts of human beings.[31] The kabbalistic notion of a broken fragmented deity in need of repair became a staple of mystical theology since the Middle Ages.[32]

Kabbalistic Interpretation – Closer to the Biblical Original

Rabbinic and mystical interpretations of an evolving, impressionable, at times fragmented and suffering, God, emerge more naturally from the original sense of a personal interventionist God subject to emotions and affectation in the Hebrew Bible as well as its rabbinic overlay.[33]

Thus, a mythic continuum stretches from the Bible through rabbinic midrash, kabbalah, and onward. Conversely, the philosophical abstractions consistent with notions of divine perfection actually require a violent distortion of the original text, imposing a notion of the deity that is foreign both to the written text and its voluminous oral traditions.

Modern Critiques of the Philosophical Approach

Contemporary Jewish theology continues the assault on rationalist understandings of YHWH as “pure Being.”

Buber – The Need for a Vital God

Martin Buber (1878-1965) forcefully challenged the philosophical notions of God, both on philological grounds, and on the claim that they are abstractions of a kind that do not usually arise in periods of increasing religious vitality. According to Buber, “religious vitality” gives rise to a vital and dynamic being, a God of presentness, rather than a static definitive one. For him, “It means happening, coming into being, being there, being present, being thus and thus; but not being in an abstract sense.”[34]

Hertz – Active Manifestation not Passive Being

Earlier, Rabbi Joseph H. Hertz (1872-1946), in his commentary on Exod. 3:14, until recently, the standard edition of the Pentateuch used in most Modern Orthodox congregations, had noted that the name “must not be understood in the philosophical sense of mere ‘being’, but as an active manifestation of the Divine existence.”[35]

Malbim’s Compromise

God further qualifies the announcement of His name to Moses in the verse following the disclosure of Ehyeh asher Ehyeh by historically contextualizing YHWH to enhance the name’s recognizability for the wider community:

יְ-הוָה אֱלֹהֵי אֲבֹתֵיכֶם אֱלֹהֵי אַבְרָהָם אֱלֹהֵי יִצְחָק וֵאלֹהֵי יַעֲקֹב שְׁלָחַנִי אֲלֵיכֶם.

YHWH the God of your ancestors, the God of Abraham, the God of Isaac, the God of Jacob sent me to you. (3:15)

He then supplements it further with an assertion about its temporal intelligibility:

זֶה שְּׁמִי לְעֹלָם וְזֶה זִכְרִי לְדֹר דֹּר.

This is my name for all time And this is my memorial for successive generations.

The nineteenth century exegete, Meïr Leibush ben Yehiel Michel Wisser (d. 1879), known as Malbim, hybridizes the traditions about the name’s meaning. He parses what is patently an emphatic avowal of durability into a proclamation of two different dimensions to the human encounter with God, resulting in different perceptions of God:

שלעולם מציין הזמן התמידי הבלתי מתחלק, ולדור דור מציין הזמן המתחלק לפי הדורות,

For le’olam expresses time that is continuous and indivisible while dordor expresses time that is periodic, segmented according to each generation.

By distinguishing between different senses of temporality conveyed by the terms “forever” (le’olam) and “every generation” (dor dor), the phrase conveys two facets of God’s being, one closer to the philosophical eternal immutable God, and the other a relational God persistently in flux. Accordingly, the first term signifies,

והוא שמי העצמי זה לא ישתנה בשום דור והוא עומד לעולם בהנהגה קבועה בלתי משתנה.

This is His essential name, it does not change in any generation, and He stands constant for every period and conducts Himself in a fixed and immutable manner.

At the same time, the second term connotes that,

שבכל דור ודור יש הנהגה חדשה וזוכרים את מעשיו באופן אחר כמ”ש אלהי אברהם אלהי יצחק, שבדור יצחק נשתנה ההנהגה האלהית ממה שהיה בימי אברהם.

Each generation experiences a novel mode of governance and remembers His ways differently as it states “the God of Abraham, the God of Isaac,” meaning that divine governance in Isaac’s generation was different than in Abraham’s.

A Generation-Specific God

Each generation, in a sense, relates to a different God who is transformed by the particular encounters engendered by unique temporal and human contexts. That “memorial” associated with “successive generations” is associated with the flux of history, conditioning any knowledge of God on Israel’s experiences of God at different junctures within history. Preserving those memories of how each generation experiences its own version of God’s name thus presents a prime instance of Yosef Haim Yerushalmi’s evaluation of the role of memory in the life of Israel as “crucial to its faith, and ultimately to its very existence.”[36]

Heschel’s Advice: YHWH Simply as God’s Personal Name

Abraham Joshua Heschel’s (1907-1972) stand on the issue of God’s name, is, I believe, crucial for the sake of the ongoing viability of Jewish theology, whether for critical scholars, philosophers, theologians, pedagogues, or rabbinic experts. In 1968, he addressed the annual conference of Solomon Schechter School principals, offering advice on how they should teach theological ideas “in the Jewish way of thinking.”

In that talk, he distinguished between a “notion,” identified with the Greeks and the rationalist school of thought, and a “name,” associated with the traditions endorsing a personal God of history. For him the two are so different as to be “profoundly incompatible,” and therefore, Heschel presents the two alternatives as an either/or choice.

Heschel was categorical about his own choice. In this talk to Jewish educators, those most responsible for the perpetuation of Jewish thought to the next generation of potential scholars, theologians, philosophers, and halakhic authorities, he advocated a named God over and against theoretical conceptions of God. In line with those views noted previously, represented by midrashic traditions, kabbalah, Rashi, and Buber, Heschel insisted they treat YHWH as evocative rather than descriptive. He thus admonished them that “the God of Israel is a name, not a notion…don’t teach notions of God, teach the name of God.”[37]

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

January 17, 2017

|

Last Updated

November 30, 2025

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Prof. James A. Diamond is the Joseph and Wolf Lebovic Chair of Jewish Studies at the University of Waterloo and former director of the university’s Friedberg Genizah Project. He holds a Ph.D. in Religious Studies and Medieval Jewish Thought from the University of Toronto, and an LL.M. from New York University’s Law School. He is the author of Maimonides and the Hermeneutics of Concealment, Converts, Heretics and Lepers: Maimonides and the Outsider and, Maimonides and the Shaping of the Jewish Canon.

Essays on Related Topics: