Edit article

Edit articleSeries

A Moral Value in the Song of Songs

כל הכתובים קודש ושיר השירים קודש קודשים – All the Writings are holy, but Song of Songs is the Holy of Holies

A Strange Book

The Song of Songs is a strange book to find in the Bible. It is a love song (or, in one view, a collection of love songs) devoid of reference or even allusion to God, Torah, and Israel’s historical experience. It is devoted rather to an intimate view of two young people, a man and a woman. Since they are caught in a moment of transition to adulthood, they could be called “boy” and “girl,” or, more exactly נער and נערה. The woman is also called the Shulammite, which probably means “the flawless one.” I will refer to them by whatever seems appropriate to the moment in the Song.

The Rabbis accepted the Song as sacred scripture because they read it as an allegory of God’s love for Israel. In my view, this allegory is foreign to the book’s original meaning. Still, it has become one of the book’s meanings, one legitimized by the history of Jewish interpretation. But, the book as interpreted allegorically is virtually a different book from the Song in its original sense, and it is the meaning and the poetry of the latter that engages me.

Making Love

The Song is clear in its vision of sexual love, though its clarity has been clouded by traditional assumptions and religious proprieties. This vision is expressed in allusions that are virtually explicit.[1] The lovers are not married, though they certainly intend to be: The woman is still under her brothers’ control (1:6), living at her family’s house, “the house of my mother” (8:2) not at her lover’s; he must sneak up to her house at night to speak to her (2:9; 5:2), and when he suddenly seems to disappear, she chases about the city at night, searching for him desperately (3:1-4; 5:6). They are not at any point said to be married; the man calls the woman kallah, “bride” in the poem in 4:8-5:1 as a term of endearment, reflecting a hope, not a reality.

To be sure, there is mention of Solomon’s wedding (3:7-11), which many scholars have interpreted as referring to the lovers’ own. But the couple is unmarried in the rest of the book. More likely, the passage is a fantasy. When the woman says, “Behold Solomon’s couch!” she is declaring her lover as a king and their bower a royal pavilion, as in 1:12-17. Nor are the couple yet betrothed, for she wishes she could have her love publically recognized (8:1-2). Their betrothal lies in the future (8:8-10). As for now, they are two young people who alone recognize that this is a love that their will last till death.

The two lovers make love in many ways. They lavish glorious praise on each other. They kiss deeply, mouth to mouth (1:2). They spend the night with him nestled between her breasts like a pouch of fragrant henna, as they lie under a bower of trees (1:17). What they do that night is left to the reader’s imagination, for the book’s treatment of sex is subtle, but not too subtle. This bower, to the woman, is a royal couch for her lover, who is her “king” (1:12-13).[2] This “king” brought her to his chambers (1:4), later revealed to be their bower in the field (1:17). They offer each other “love,” called dodim, a word that always refers to sexual love,[3] and they exult in each other’s dodim (1:4; 4:10). Later, the woman declares proudly, “I am my beloved’s and his passion is for me.” (The word for passion, teshuqah, means sexual desire; it is the word used of woman’s desire for her mate in Genesis 3:16.)

She is a “garden,” locked and not available (4:12) to anyone but her lover. Him she invites in (4:16), and her garden becomes his too (5:1). He enters, and there he “eats” and “drinks,” partaking of her “fruits” (5:1). At the end of this verse, an unidentified voice, perhaps the women of Jerusalem (who are the Shulammite’s companions), perhaps the author’s, urges: “Eat well, O friends, drink yourselves drunk on dodim.” (For the unmistakable sexual sense of this metaphor, see Proverbs 5:19[4] and 7:18.) Later, the Shulammite invites her lover to go with her to the field. There, she says, “We’ll pass the night in the countryside,” and “there I will give you my dodim” (7:13). Those fruits, it is clear, are her blossoming sexuality. And if there were any doubt about this, she says that “at our doors are all sorts of luscious fruits, fruits both new and old: my dodim,[5] which I’ve saved up for you” (7:14).

Love Songs in Egypt

Though the Song of Songs is strange in the Bible, it is less so if we broaden our notion of the Israelite culture-sphere to include its neighbors, in particular the great cultures of Mesopotamia and Egypt. A body of love songs from ancient Egypt bears significant similarities to the Song and may in fact belong to an artistic tradition that reached Israel.[6] Some fifty Egyptian love songs, dating from 1300-1150 BCE, are extant, in whole or in part. For a sample, click here. These predate the Song of Songs by centuries.

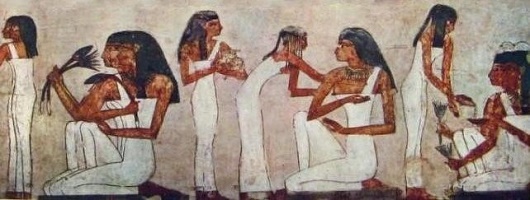

These songs were probably sung for entertainment at banquets of the sort depicted in many Egyptian tombs. They show the earthly pleasures that wealthy people hoped to enjoy for eternity. Here is an example from the picture of the women’s section of the banquet in a tomb from the 15th century B.C.E:

The guests at these banquets were entertained by singers and dancers. One can almost hear the beauty of their song and feel the grace of their dance in the art that depicts them, as in this painting:[7]

Songs of various kinds are quoted in these scenes. Love songs don’t happen to be among them; still, there is some strong indirect evidence that they too were sung. Some of the motifs common in the love songs also occur in the snippets of verse quoted in the murals. Also, three groups of love songs are called “entertainment,” literally “diversion of the heart,” and the murals sometimes label themselves in the same way.[8] Moreover, participants often say to each other, “divert your heart.”

By analogy we can suggest that the Song of Songs was sung in similar circumstances. Rabbi Akiva is an unwilling witness to this use of the Song when he complains: “Whoever warbles the Song of Songs at houses where there is feasting (battey hammista’ot), treating it like an ordinary song, has no portion in the world to come” (Tosefta Sanhedrin 12:10).[9] Thus, as late as the early second century C.E., when the Song’s sacral status was not in doubt, Jews were still singing it to “divert the heart.”

Monologue Versus Dialogue: Comparing Israelite and Egyptian Love Poems

The Song has enough in common with the Egyptian love songs to suggest that they were influenced by the same international tradition. But even without the supposition of historical connection, the two groups of songs are similar enough to make literary comparison useful, often by highlighting significant differences. On this occasion, I want to compare one aspect of their artistry: the way the lovers speak to and about each other.

All the Egyptian love songs are monologues. Even in the songs that quote both lovers, they do not speak to each other or seem to hear one another. The following monologue is part of a song in which a woman invites her beloved to the field and offers him her love (compare Song 7:12-14).

In [the garden] are “Exaltation” trees,

before which one is exalted:

I am your favorite sister

(“Sister” means beloved, as in the Song.)

yours like the field

planted with flowers

and with all sorts of fragrant plants.

(Compare Song 4:12-16.)

Pleasant is the canal within it,

(Song 4:13 refers to the “channels” [shelaḥim] in the woman’s “garden.”)

which your hand scooped out,

while we cooled ourselves in the north wind:

a lovely place for a stroll

with your hand on mine!

My body is content,

and my heart rejoices

as we walk together.

The sound of your voice is pomegranate wine…

(Compare Song 2:14.)

Often the lovers’ words are thought, not spoken. In a song of seven wishes, a man says:

If only I were her little signet,

the keeper of her finger!

I would see her love

each and every day …

(A similar image to Song 8:6 but how differently it is used!)

In one song, a man and a woman speak (or think) in alternate stanzas but never hear each other. He is at home as she passes by one day. They immediately fall in love. They praise each other and long for each other and are love-sick, but nothing happens, for they are not emboldened to approach each other. In the last stanza, the man can only groan, “Seven whole days have passed since I have seen my sister. Illness has invaded me.”

Monologue works well for the Egyptian poets, because they are primarily interested in exploring the feelings of love, both the pleasant and the painful. Their poems do not portray relationships, even when the lovers are presumed to be together.

The Song of Songs, in contrast, contains true dialogue. Though monologues are embedded in the lovers’ words, the lovers speak to and respond to each other. The Song brings out the interaction of the loves and shows the mutuality of their communication most vividly by making the lovers’ words echo each other’s.

The echoing sometimes happens at a distance, as when the man says, “Arise my darling, and come away,” and invites the woman to come with him to the blossoming fields (2:10-14). Later, in similar words, she offers him the same invitation: “Come, my beloved; let us go to the field…” (7:12-14).

Elsewhere we hear the echoing in a single exchange of words, as in 1:15-16. The man says, “How beautiful you are, my darling! How beautiful you are. Your eyes are doves.” Without pause, the woman takes up his words and returns the compliment: “How beautiful you are, my beloved—delightful too. And our bed is verdant.”

Their words intertwine most closely in the exchange in 2:1-3. The woman says:

I’m just a crocus of the Sharon,[10]

a lily of the valleys. (2:1)

This is a modest demurral: I’m just one among a thousand, just one woman in myriads. Perhaps she’s fishing for a compliment. Her lover immediately catches the gist and sends it back to her as praise:

As a lily among the thorns,

so is my darling among the women. (2:2)

And she does the same to him:

As an apple tree among the tree of the wood:

thus is my beloved among the youths. (2:3)

In the interleaving of their words and the mirroring of their souls, the Song reveals a love that “interanimates two soules.”[11]

Believing in the Ideal of Love: Then and Now

In portraying sexual love, the Song is not depicting a social reality and certainly not offering a model of behavior. Premarital sex in ancient Israel would have resulted in pregnancy and outraged the family. According to Exodus 22:15, the man (in a consensual seduction) would have been obliged to pay the bride price to the woman’s father and to marry her. This may sometimes have been the desired outcome and a satisfactory resolution. But the father could prohibit the marriage and, in the steely calculus of patriarchal society, the seducer would still have to compensate him for the decline in the bride price she could bring (Exodus 22:16).

But this not the world of the Song. It describes a fantasy world, one which the listeners can enjoy and imagine themselves part of. This fantasy is never titillating or lewd. It is tender and devoted to the lovers. But the love it describes could not have been safely put into action.

It is different today. Birth control allows the deferral of pregnancy until the desired time, and, in Western society at least, (putting aside religious objections for the moment) premarital intercourse is widely considered natural and accepted with equanimity. It has also become a fact of life in many social circles, whatever religious authorities, of whatever religion, may wish. The Song’s vision can now be read as an ideal and, in many fortunate lives, realized at least in part.

The sexual acts in the Song are truly lovemaking. They are one aspect of the intense love and commitment between the partners. Their commitment is egalitarian and exclusive, both qualities being perfectly expressed in the declaration of mutual possession: “I am my beloved’s and my beloved is mine” (6:3). She is his garden, and he “grazes among the lilies” (6:3). She is his vineyard, and he treasures this privileged possession above the fabled riches of Solomon’s vineyards, real and metaphorical (8:11-12). The lovers’ commitment, as they see it, must last and cannot be defied, for “Love is stronger than death” (8:6). It is a love that will not tolerate interference, whether by rival lovers or by intrusive family, for, as the Shulammite warns rather fiercely, “jealously is as harsh as the grave” (8:6).

This is an ideal of love. In reality, it is not infallible or inevitable, and it is not immune to mundane realities and personal changes. Nor can we know that any one such relationship will grow into marriage. But the ideal is not impossibility and is not to be dismissed as an adolescent crush. The poet treats this relationship with affection but also complete seriousness, never viewing the characters with condescension or a knowing cynicism, as if to say, “It won’t last, kids.” Today, this ideal can be cherished and affirmed as a moral value, one that rejects behaviors, such as hooking-up, that trivialize and endanger sex. The sexual ethic that I see as implicit in the Song could be extended today to other kinds of relationships beyond the one portrayed in the Song.

Delighting in the Erotic Charms of Your Spouse

There is a moral lesson here: to embrace the ideal of sexual love embodied in the Song. Young people, and not only the young, should read the Song for its vision of erotic love, immerse themselves in it, fantasize themselves in it, and then, when the time is right (called “the time of dodim” in Ezekiel 8:16), make it their reality. This lesson has great persuasive force, for it is not preached, as moral lessons usually are, but rather conveyed through the most delightful and enticing of poems, the Song of Song, the Sublime Song.

Although this ideal experience cannot always thrive in mundane life the fun need not end with marriage. In the book of Proverbs, a father first warns his son against the dangers of sex with a “strange woman,” that is to say, a woman not his own (5:1-14). Then he exhorts the youth—in allusions whose meaning we know from the Song of Songs—to delight in the erotic charms of his own wife:

Drink water from your own fountain,

liquids from your well. …

Let your fount be blessed,

take pleasure in the wife of your youth:

a loving doe, a graceful gazelle.

Let her dodim ever slake your thirst,

lose yourself always in her love. (Prov 5:15, 18-19)

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

April 17, 2014

|

Last Updated

March 16, 2025

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Prof. Rabbi Michael V. Fox , z”l, is the Jay C. and Ruth Halls-Bascom Professor (Emeritus) of Hebrew at the University of Wisconsin-Madison until his retirement in 2010. He received his his Ph.D. in Bible, Semitics, and Egyptology from Hebrew University, and his Rabbinic ordination from Hebrew Union College. Fox’s books include studies of the Song of Songs and the Egyptian love songs, Esther, Ecclesiastes, and Proverbs.

Essays on Related Topics: