Edit article

Edit articleSeries

“Esau Hates Jacob” - But Is Antisemitism a Halakha?

Jacob meets his brother Esau. Bible Pictures and What They Teach Us by Charles Foster, 1897.

The Split between the Brothers

After more than twenty years apart, Jacob and Esau finally reunite. They had not parted on good terms. Jacob had duped his father and stolen the blessing meant for Esau; Esau became very angry and wanted to kill him (Genesis 27:41).

Hearing of these plans, Rebekah took action, telling Jacob (Genesis 27:42-45):

…הִנֵּה עֵשָׂו אָחִיךָ מִתְנַחֵם לְךָ לְהָרְגֶךָ: וְעַתָּה בְנִי שְׁמַע בְּקֹלִי וְקוּם בְּרַח לְךָ אֶל לָבָן אָחִי חָרָנָה: וְיָשַׁבְתָּ עִמּוֹ יָמִים אֲחָדִים עַד אֲשֶׁר תָּשׁוּב חֲמַת אָחִיךָ: עַד שׁוּב אַף אָחִיךָ מִמְּךָ וְשָׁכַח אֵת אֲשֶׁר עָשִׂיתָ לּוֹ וְשָׁלַחְתִּי וּלְקַחְתִּיךָ מִשָּׁם:

“Your brother Esau is consoling himself by planning to kill you. 43 Now, my son, listen to me. Flee at once to Haran, to my brother Laban. 44 Stay with him a while, until your brother’s fury subsides— 45 until your brother’s anger against you subsides—and he forgets what you have done to him. Then I will fetch you from there.”

Jacob followed his mother’s advice and fled to Laban. After we learn that Esau marries yet another wife, one presumably more to his parents’ liking, we hear nothing about him until Jacob’s return to Canaan.

His mother had promised that when Esau’s anger subsided, she would fetch Jacob and she also intimated that this would take only a short while (literally, a few days, or perhaps a few years; ימים אחדים). The Torah never says that Rebekah sent word to Jacob that it was safe to come home. Rather it was God, more than twenty years later, who tells Jacob to return to Canaan and promises to be with him (Genesis 31:3).

On his return trip, when Jacob comes close to Esau’s territory, he sends messengers to Esau, presumably to determine whether he should still be afraid. He hears that Esau is on his way over with 400 men (Gen 32:7), and concludes that Esau is still eager to kill him or at least to do him harm, so he initiates various strategies—prayer (vv. 10-13), bribes (vv. 14-22) and preparation for the worst (vv. 8-9)[1] —in an attempt to deal with the danger.

Rashbam – He Had Nothing to Fear

While almost all Jewish commentators assume that Jacob drew the correct conclusion about Esau’s evil intentions, as is typical, Rashbam goes against the consensus. He argues that Jacob misunderstood Esau’s friendly intentions. Not only that, Jacob failed to trust God’s promise to be with him, and he eventually was punished for that faithlessness when he was injured by the man/angel (Gen 32:26).[2]

Either because Jacob’s tactics successfully won over his brother, or because Esau had calmed down independently, the meeting of the brothers goes well:

וַיָּרָץ עֵשָׂו לִקְרָאתוֹ וַיְחַבְּקֵהוּ וַיִּפֹּל עַל צַוָּארָו וַׄיִּׄשָּׁׄקֵ֑ׄהׄוּׄ וַיִּבְכּוּ:

Esau ran to greet him. He embraced him and, falling on his neck, he kissed him; and they wept. (Genesis 33:4)

A Dotted Kiss

Unusually, the word וַיִּשָּׁקֵהוּ (he kissed him) is written in the Torah scroll with a dot above each of its six letters. What is the meaning of these “puncta extraordinaria,” the technical term for these dots? How did later Jewish tradition relate to them and specifically to the kiss in this verse?[3]

Scribal Notation for Erasure

Professor David Weiss Halivni argues that Ezra the Scribe added dots on top of various letters or words in the Torah as part of his project of trying to clean up a “maculate” text, one that contained many errors. Instead of erasing the words, he placed dots above them to signify that they might not belong in the text.[4] (Presumably this explanation implies that the scribes were suggesting that Esau never did kiss Jacob.) This practice goes back at least to the Qumran community.[5]

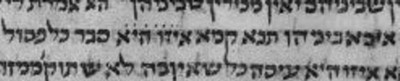

We also know that in later periods of history, scribes often put dots over words instead of erasing them, as in this picture of a pre-modern Talmud manuscript where the scribe (or someone later?) recognized that two words איזו היא were written by mistake:[6]

Drawing Attention

A different theory, propounded by Professor Saul Lieberman, is that dots were used by ancient scribes as a way of drawing attention to a word.

In the classical Greek texts the διπλῆ served a similar purpose. It called attention to a remarkable passage, to a πολύσημυς λέξις to a text which has many significations. Any Greek grammarian upon finding such a critical mark in a classic text without a commentary would ask: τί ποτε σημαίνει “What in the world does it signify?” The Rabbis did the same thing.[7]

The Tannaitic midrash halakha work from around the 3rd century, Sifrei Bemidbar, provides explanations for the ten passages in the Torah where dots appear above letters, including our example, which Rashi quotes in his commentary to this verse:

וישקהו – נקוד עליו, ויש חולקין בדבר הזה בברייתא דספרי, יש שדרשו נקודה זו לומר שלא נשקו בכל לבו. אמר ר’ שמעון בן יוחאי הלכה היא בידוע שעשו שונא ליעקב, אלא שנכמרו רחמיו באותה שעה ונשקו בכל לבו:

וישקהו has dots above it. In the Sifrei we find a dispute about how to interpret [these dots]. Some say that the dots mean that he did not kiss him wholeheartedly. [However] Rabbi Shimon bar Yohai says, “It is a well-known halakha that Esau hates Jacob. Nevertheless, at that moment he became merciful and he kissed him wholeheartedly.”

The phrase הלכה בידוע (it is a well-known halakha) is unusual. It appears nowhere else in classical rabbinic literature and it is unclear what is “halakhic” about it.

The Inevitability of Antisemitism: R. Moshe Feinstein

Whatever Rashi or the Sifrei meant by the phrase, in modern times, people cite it as proof of the inevitability and universality of antisemitism. Consider how the prominent American halakhic authority, Rabbi Moshe Feinstein (1895-1986) interpreted the phrase in the early 1970s, when he answered a halakhic question that he had received from England.

Jews in England claimed that the government was discriminating against Jewish private schools and underfunding them, compared to government funding for other private schools. The British Jewish community considered suing the British government at the European Court for Human Rights. One rabbi in England turned to Rabbi Feinstein for his opinion about launching such a suit.

Rabbi Feinstein wrote that, in general, he supported initiatives that could lead to more government support for Jewish education:

ודאי פשוט וברור שיש להשתדל אצל הממשלה שיתמכו בבתי ספר שהיהודים יסדו לעצמן.

Certainly it is obvious that one should lobby the government to support schools established by Jews for themselves.

But his attitude to suing the British government in a European court was different:

לתבוע למשפט אשר נמצא במדינה אחרת שגם ענגלאנד שייך להם ולבוא בקובלנא לפני השופטים על השרים של ענגלאנד אשר עושים עוולה נגד היהודים ודאי יש לחוש להטלת איבה מהממשלה להיהודים שזה אפשר שחס ושלום יביא לתוצאות לא טובות בהרבה … כי צריך לידע שהשנאה לישראל מכל האומות היא גדולה גם ממלכיות שנוהגין בטובה, וכבר אמרתי על הלשון שהביא רש”י בפירוש החומש… על קרא דוישקהו אמר רשב”י הלכה היא בידוע שעשו שונא ליעקב

But we must worry that suing the government at a court in another country with which England is associated, and complaining to the judges there that the ministers in England are harming the Jews is likely to cause hatred toward Jews on the part of the government. The result could be far worse than the original problem… For we have to realize that hatred of the Jews by all nations is actually great, even in the nations that behave well [toward Jews]. I have already explained concerning Rashi’s language in his Torah commentary… on the word וישקהו: Rabbi Shimon bar Yohai says: “It is a well-known halakha that Esau hates Jacob.”

דמה שייך זה להלכה, דהוא כמו שהלכה לא משתנית כך שנאת עשו ליעקב לא משתנית דאף אלו שנוהגות באופן טוב שנאתן גדולה בעצם

And why is the word halakha relevant here? It is because just as halakha never changes, so also Esau’s hatred of Jacob never changes. Even in those [nations] that behave well [toward Jews], their hatred [of Jews] is actually strong. [8]

Rav Moshe Feinstein is not the only modern Jewish writer to see “Esau Hates Jacob” as expressing the inherent antisemitism of gentiles. In an article for Mishpacha magazine, R. Emanuel Feldman wrote

Two thousand years ago, our Sages declared prophetically: “Halachah hi: Eisav sonei es Yaakov,” it is a universal law: Esau hates Jacob. This is one halachah that Esau maintains religiously.[9]

Even authors who are uncomfortable with the concept of an inherent antisemitism in gentiles struggle to interpret this statement in a different light.[10]

Does Esau Represent All Gentiles?

Is the interpretation of “Esau hates Jacob” as a guarantee for antisemitism correct or overstated? Even if the word “Esau” is a code word for gentiles, for the second-century Rabbi Shimon bar Yohai it would refer specifically to the Romans, with their often brutal occupation of the land of Israel.[11]

R. Shimon bar Yohai’s Original Statement

Interpretations such as that of R. Feinstein find support in the phrase “it is a known halakha” found in the standard printing of the Sifrei and quoted by Rashi. Nevertheless, the preponderance of manuscripts of Sifrei Numbers do not have this phrase. Here is how the text reads in the new, excellent edition of Sifrei Numbers (69), edited by Professor Menachem Kahana of the Hebrew University:

…וישקהו [נקוד עליו][12] שלא נשקו בכל לבו ר’ שמעון בן יוחיי אומר והלא בידוע שעשו שונא ליעקב אלא נהפכו רחמיו באותה שעה ונשקו בכל לבו.

Va-yishshaqehu [he kissed him] has dots above it [to teach us] that he [Esau] did not kiss him [Jacob] wholeheartedly. [However,] Rabbi Shimon bar Yohai says: “It is well-known that Esau hates Jacob. Nevertheless, at that moment he became merciful and he kissed him wholeheartedly.”

Where other texts read הלכה בידוע, the best manuscripts read והלא בידוע, and considering the similarity in the Hebrew words, the former phrase could easily be a mistake.[13] In other words, Rabbi Shimon bar Yohai is not claiming that any “halakha” is connected to the hatred of Jews. Menachem Kahana, in his commentary on this passage, traces the reading “halakha” to a minority tradition in the manuscripts that reached France, leading Rashi to perpetuate this misreading.[14]

Esau Hates Jacob – It Means What It Says

So what was Rabbi Shimon bar Yohai really saying? He was not making a sweeping statement about Jews and gentiles but interpreting the biblical story of the two brothers, Jacob and Esau. If Esau had actually never calmed down from his anger of twenty years before, his kiss requires an explanation, and the dots call attention to this.

Some midrashim suggest that the kiss was actually an attempt to bite Jacob,[15] or some other form of duplicitous action.[16] Rabbi Shimon bar Yohai represents the more charitable understanding of Esau. The dots on the word tell us that he really did kiss his brother sincerely despite his well-known previous antipathy towards him.

Challenging the Idea of Universal Antisemitism

Given this, it does not make sense to say that Rabbi Shimon Bar Yohai’s opening words about Esau’s hatred are a statement about the inevitability of gentile hatred of Jews. It is unfortunate that this statement about the alleged halakha of antisemitism continues to be quoted so widely. Antisemitism has sadly not passed from the world and we Jews must remain vigilant. But the attitude that antisemitism is hiding under the surface everywhere, even in countries where Jews are treated well, cannot be found in Judaism’s earliest writings, neither in the Bible nor in the Talmudic period.[17]

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

November 11, 2016

|

Last Updated

December 23, 2025

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Prof. Rabbi Marty Lockshin is Professor Emeritus at York University and lives in Jerusalem. He received his Ph.D. in Near Eastern and Judaic Studies from Brandeis University and his rabbinic ordination in Israel while studying in Yeshivat Merkaz HaRav Kook. Among Lockshin’s publications is his four-volume translation and annotation of Rashbam’s commentary on the Torah.

Essays on Related Topics: