Edit article

Edit articleSeries

Judah’s Restoration: The Meaning of Ezekiel’s Vision of the Dry Bones

Ezekiel and the Valley of Dry Bones, from Histoire Sainte, ca. 1850-1880. Wikimedia

Ezekiel’s description of dry bones revived and reconstructed into living, flesh and blood bodies has evoked the imagination of authors and artists. It has inspired the words of the spiritual “Dem Bones” written by James Weldon Johnson and his brother J. Rosamond, and it lends its name to a political cartoon series published in the Jerusalem Post. The vision, however, is as complex and misunderstood as it is dramatic.[1]

Ezekiel’s Vision

YHWH brings Ezekiel into a valley filled with bones:

יחזקאל לז:א הָיְתָה עָלַי יַד יְהוָה וַיּוֹצִאֵנִי בְרוּחַ יְ־הוָה וַיְנִיחֵנִי בְּתוֹךְ הַבִּקְעָה וְהִיא מְלֵאָה עֲצָמוֹת. לז:ב וְהֶעֱבִירַנִי עֲלֵיהֶם סָבִיב סָבִיב וְהִנֵּה רַבּוֹת מְאֹד עַל פְּנֵי הַבִּקְעָה וְהִנֵּה יְבֵשׁוֹת מְאֹד.

Ezek 37:1 YHWH’s hand came upon me. I was taken out by the spirit of YHWH and set down in the valley. It was full of bones. 37:2 [YHWH] led me all around them; there were very many of them spread over the valley, and they were very dry.

The dryness of the bones shows that their owners have been dead for a long time. YHWH then asks Ezekiel a question about something that seems impossible:

יחזקאל לז:ג וַיֹּאמֶר אֵלַי בֶּן אָדָם הֲתִחְיֶינָה הָעֲצָמוֹת הָאֵלֶּה וָאֹמַר אֲדֹנָי יְ־הוִה אַתָּה יָדָעְתָּ.

Ezek 37:3 I was asked, “O mortal, can these bones live again?” I replied, “O Sovereign YHWH, only You know.”

As Ezekiel doesn’t answer the question, YHWH answers by commanding Ezekiel to prophesize to the bones themselves that they will indeed return to life:

יחזקאל לז:ד וַיֹּאמֶר אֵלַי הִנָּבֵא עַל הָעֲצָמוֹת הָאֵלֶּה וְאָמַרְתָּ אֲלֵיהֶם הָעֲצָמוֹת הַיְבֵשׁוֹת שִׁמְעוּ דְּבַר יְ־הוָה. לז:ה כֹּה אָמַר אֲדֹנָי יְ־הוִה לָעֲצָמוֹת הָאֵלֶּה הִנֵּה אֲנִי מֵבִיא בָכֶם רוּחַ וִחְיִיתֶם. לז:ו וְנָתַתִּי עֲלֵיכֶם גִּדִים וְהַעֲלֵתִי עֲלֵיכֶם בָּשָׂר וְקָרַמְתִּי עֲלֵיכֶם עוֹר וְנָתַתִּי בָכֶם רוּחַ וִחְיִיתֶם וִידַעְתֶּם כִּי אֲנִי יְ־הוָה.

Ezek 37:4 And I was told, “Prophesy over these bones and say to them: O dry bones, hear the word of YHWH! 37:5 Thus said Sovereign YHWH to these bones: I will cause breath to enter you and you shall live again. 37:6 I will lay sinews upon you, and cover you with flesh, and form skin over you. And I will put breath/wind (ruaḥ) into you, and you shall live again. And you shall know that I am YHWH!”

Ezekiel speaks the words YHWH commands, and suddenly the bones turn into bodies again, but without life:

יחזקאל לז:ז וְנִבֵּאתִי כַּאֲשֶׁר צֻוֵּיתִי וַיְהִי קוֹל כְּהִנָּבְאִי וְהִנֵּה רַעַשׁ וַתִּקְרְבוּ עֲצָמוֹת עֶצֶם אֶל עַצְמוֹ. לז:ח וְרָאִיתִי וְהִנֵּה עֲלֵיהֶם גִּדִים וּבָשָׂר עָלָה וַיִּקְרַם עֲלֵיהֶם עוֹר מִלְמָעְלָה וְרוּחַ אֵין בָּהֶם.

Ezek 37:7 I prophesied as I had been commanded. And while I was prophesying, suddenly there was a sound of rattling, and the bones came together, bone to matching bone. 37:8 I looked, and there were sinews on them, and flesh had grown, and skin had formed over them; but there was no breath in them.

The passage is reminiscent of Job’s description of fetal formation, with skin and flesh being woven onto bones:

איוב י:יא עוֹר וּבָשָׂר תַּלְבִּישֵׁנִי וּבַעֲצָמוֹת וְגִידִים תְּסֹכְכֵנִי.

Job 10:11 You clothed me with skin and flesh and wove me of bones and sinews.

Similarly, R. Joseph Kara (11th cent.), referencing a rabbinic tradition, sees this process as the inverse of dying:

רבי יוסף קרא יחזקאל לז:ה–ו ורבותינו ז"ל משלו לאדם הנכנס למרחץ: מה שהוא מתפשט באחרון, הוא לובש תחילה ביציאתו מן המרחץ. כך מידתו של הקב"ה: מה שפשט מעליו בסוף, הוא פורע בתחילה כשבא ללובשו. שבתחילה מרקב ומתפשט מעליו העור, ואחר כך הבשר, ואחר כך גידין, ואחר כך העצמות. וכשבא ללובשן, לובש בתחילה העצמות, ואחר כך הגידים, ואחר כך הבשר, ואחר כך העור.

R. Joseph Kara Ezek 37:5–6 Our Rabbis compared this to a person entering a bathhouse: what he takes off last, he puts on first when he leaves the bathhouse. So too is the way of the Blessed Holy One: What he removed from him last he returns first when he comes to dress [the deceased in life]. First, the body decomposes, and the skin comes off, afterwards the flesh, then the ligaments, and after that the bones. When [God] comes to dress them [in life], he first gives the bones, then ligaments, then flesh, and after that skin.

YHWH then has Ezekiel command the four winds—the same Hebrew words as breath—to come breathe life into the bodies, after which they come to life:

יחזקאל לז:ט וַיֹּאמֶר אֵלַי הִנָּבֵא אֶל הָרוּחַ הִנָּבֵא בֶן אָדָם וְאָמַרְתָּ אֶל הָרוּחַ כֹּה אָמַר אֲדֹנָי יְ־הוִה מֵאַרְבַּע רוּחוֹת בֹּאִי הָרוּחַ וּפְחִי בַּהֲרוּגִים הָאֵלֶּה וְיִחְיוּ. לז:י וְהִנַּבֵּאתִי כַּאֲשֶׁר צִוָּנִי וַתָּבוֹא בָהֶם הָרוּחַ וַיִּחְיוּ וַיַּעַמְדוּ עַל רַגְלֵיהֶם חַיִל גָּדוֹל מְאֹד מְאֹד.

Ezek 37:9 Then [YHWH] said to me, “Prophesy to the breath/wind (ruaḥ), prophesy, O mortal! Say to the breath: Thus said the Sovereign YHWH: Come, O breath, from the four winds, and breathe into these slain, that they may live again.” 37:10 I prophesied as I was commanded. The breath entered them, and they came to life and stood up on their feet, a vast multitude.

The German Bible professor, Karin Schöpflin, notes that the passage reflects the two-stage process in which humans are created in the second creation story in Genesis,[2] beginning with the formation of the body from dust followed by life from YHWH’s breath:

בראשית ב:ז וַיִּיצֶר יְ־הוָה אֱלֹהִים אֶת הָאָדָם עָפָר מִן הָאֲדָמָה וַיִּפַּח בְּאַפָּיו נִשְׁמַת חַיִּים וַיְהִי הָאָדָם לְנֶפֶשׁ חַיָּה.

Gen 2:7 YHWH God formed man from the dust of the earth. He blew into his nostrils the breath of life, and man became a living being.

YHWH then explains the vision’s meaning: The bones represent the exiles, who identify themselves as “dry bones,” much like those that are left scattered about the mysterious valley, and express their hopelessness:

יחזקאל לז:יא וַיֹּאמֶר אֵלַי בֶּן אָדָם הָעֲצָמוֹת הָאֵלֶּה כָּל בֵּית יִשְׂרָאֵל הֵמָּה הִנֵּה אֹמְרִים יָבְשׁוּ עַצְמוֹתֵינוּ וְאָבְדָה תִקְוָתֵנוּ נִגְזַרְנוּ לָנוּ.

Ezek 37:11 And I was told, “O mortal, these bones are the whole House of Israel. They say, ‘Our bones are dried up, our hope has perished. We are cut off.’

The vision of their renewal is YHWH’s promise that the exiles are not all dried up and there is room to hope:

יחזקאל לז:יב לָכֵן הִנָּבֵא וְאָמַרְתָּ אֲלֵיהֶם כֹּה אָמַר אֲדֹנָי יְ־הוִה הִנֵּה אֲנִי פֹתֵחַ אֶת קִבְרוֹתֵיכֶם וְהַעֲלֵיתִי אֶתְכֶם מִקִּבְרוֹתֵיכֶם עַמִּי וְהֵבֵאתִי אֶתְכֶם אֶל אַדְמַת יִשְׂרָאֵל. לז:יג וִידַעְתֶּם כִּי אֲנִי יְ־הוָה בְּפִתְחִי אֶת קִבְרוֹתֵיכֶם וּבְהַעֲלוֹתִי אֶתְכֶם מִקִּבְרוֹתֵיכֶם עַמִּי.

Ezek 37:12 Prophesy, therefore, and say to them: Thus said the Sovereign YHWH: ‘I am going to open your tombs and lift you out of the tombs, O My people, and bring you to Israel’s soil. 37:13 You shall know, O My people, that I am YHWH, when I have opened your tombs and lifted you out of your tombs.

לז:יד וְנָתַתִּי רוּחִי בָכֶם וִחְיִיתֶם וְהִנַּחְתִּי אֶתְכֶם עַל אַדְמַתְכֶם וִידַעְתֶּם כִּי אֲנִי יְ־הוָה דִּבַּרְתִּי וְעָשִׂיתִי נְאֻם יְ־הוָה.

37:14 I will put My breath into you and you shall live again, and I will set you upon your own soil. Then you shall know that I, YHWH, have spoken and have acted’—declares YHWH.”[3]

In short, the Judahites in Babylonia feel that they are left to die in exile, detached from their homeland and the promises once given to their ancestors.[4] The bones are a metaphor for the exilic community, whose revival symbolizes their restoration in the land.

Is It about Future Resurrection?

Despite the vision’s simple meaning as symbolic of the future return of Judeans to their land, the image of dry bones growing skin and coming to life, and YHWH’s promise to open tombs and breathe life into the disinterred-dead lends itself to reading the text as a nod to a belief in future resurrection. Minimally, R. Moisè Isaac Ashkenazi Tedeschi of Trieste (1821–1898) accepts that the vision is meant as a metaphor, but still argues that if resurrection had not been an entrenched belief in ancient Judah, the symbolic meaning would have fallen flat:

הועיל משה, יחזקאל לז:ה ...וברור שכל מראה זו דמיון הוא, אבל אם בני ישראל לא היו מאמינים כבר בתחית המתים היו משיבים לו מְשָׁלֶךָ מכחישך, וכמו שמתים בל יחיו כן גם לנו אין תקומה...

Hoʿil Moshe, Ezek 37:5 …And it’s clear that the whole vision is in his imagination, but if the Israelites had not believed already in resurrection of the dead, they would have responded to him that “your parable contradicts you: just as the dead cannot live again, so too we have no future reestablishment…”

Many traditional commentators, ancient, medieval and modern, go further than this, understanding YHWH’s message to Ezekiel as a prophecy about future personal, bodily resurrection. This reading that goes all the way back to the Second Temple Period’s Pseudo-Ezekiel, which frames the vision in answer to Ezekiel’s question about the future recompense for the righteous:

4Q385:2 [ואמרה י-הוה] ראיתי רבים מישראל אשר אהבו את שמך וילכו 3 ב֗דרכי [לבך. וא]לה מתי יהיוֹ וֹהיכ֗כ֗ה֗ ישתלמו חסדם.

Pseudo-Ezekiel (4Q385) 2 [And I said: “O YHWH!] I have seen many (men) from Israel who have loved your Name and have walked 3 in the ways of [your heart. And th]ese things when will they come to be and how will they be recompensed for their piety?”[5]

The rabbis take such a reading for granted. For instance, the Jerusalem Talmud glosses the reference to resurrection here simply as תחית המתים, the rabbinic term for the future resurrection of the dead (j. Kilaim 9:3, Shabbat 1:3, Shekalim 3:3. Ketubot 12:3). Similarly, Midrash Song of Songs Zuta reads the passage as referring to the world to come:

מדרש זוטא - שיר השירים (בובר) א:ב ד"א "ישקני מנשיקות פיהו". שתי נשיקות הן, אחת בעולם הזה ואחת בעולם הבא, נשיקה בעולם הזה, שנאמר (בראשית ב' ז'): "ויפח באפיו נשמת חיים", נשיקה לעולם הבא, שנאמר (יחזקאל לז יד): "ונתתי רוחי בכם וחייתם".

Song Zuta (Buber) 1:2 “Let him kiss me with the kisses of his mouth”—There are two kisses (of life), one in this world and one in the world to come. The kiss in this world, as it says (Gen 2:7): “And he blew into his nostrils the breath of life.” A kiss in the world to come (Ezek 37:14): “And I will place my breath in you and you will come to life.”

In Genesis Rabbah, the passage is part of a proof that the bodies of Jews buried outside Israel will roll under the ground until they get to Israel, and only then will they be resurrected:

בראשית רבה (תיאודור-אלבק) כי"ו פרשת ויחי ר' שמעון בן לקיש בשם בר קפרא מייתי לה מן הכא (ישעיה מב:ה): "נותן נשמה לעם עליה".

Gen Rab (Theodor-Albeck) VaYechi R. Simon ben Lakish in the name of Bar Kappara brought a proof [that resurrection only happens in Israel] from here (Isa 42:5): “Who gave breath to the people upon it.”

אמ' ליה ר' סימיי: "אם כן רבותינו שבגולה הפסידו?!" אמ' לו: "מלמד שהארץ מתחלחלת כחלודות והן מתגלגלים כנודות וכיון שהן מגיעין לארץ ישראל הם חיים. הדה היא (יחזקאל לז:יד): 'ונתתי רוחי בכם וחייתם'".

Rabbi Simai said to him: “If so, then our rabbis in exile lost out [on resurrection]?” He said to him: “It teaches that the land will be perforated like caves, and [the bodies] will roll like jugs, and once they arrive in the land of Israel, they come to life. Thus it is said (Ezek 37:14): “And I will place my breath in you and you will come to life.”

In the medieval period, Don Isaac Abravanel (1437–1508) makes the explicit connection to future resurrection:

אברבנאל יחזקאל לז:יב ...הנה אני עתיד לפתוח את קברותיכם רוצה לומר שבזמן הגאולה העתידה יחיה אותם אחרי היותם קבורים שנים רבות בגלות ויוציאם מקבריהם ואחרי תחייתם יביאם אל ארץ ישראל,

Abravanel Ezek 37:12 …“For” in the future “I am going to open your tombs,” meaning to say that in the time of the future redemption, he will bring them to life after they have been buried for many years in exile, and will take them out their tombs after their resurrection and bring them to the land if Israel.

ולפי שהתחייה תהיה לצדיקים ולרשעים "אלה לחיי עולם ואלה לחרפות לדראון עולם"...

And since the resurrection will be for the righteous and the wicked, “some to eternal life, others to reproaches, to everlasting abhorrence” (Dan 12:2)…

In this second point, Abravanel quotes a verse from Daniel that unambiguously speaks of future resurrection:

דניאל יב:ב וְרַבִּים מִיְּשֵׁנֵי אַדְמַת עָפָר יָקִיצוּ אֵלֶּה לְחַיֵּי עוֹלָם וְאֵלֶּה לַחֲרָפוֹת לְדִרְאוֹן עוֹלָם.

Dan 12:2 Many of those that sleep in the dust of the earth will awake, some to eternal life, others to reproaches, to everlasting abhorrence.

Daniel is a much later text, from the second century B.C.E., envisioning a future judgment of all the individuals of the world—and it is the only biblical text that unambiguously refers to personal resurrection. Ezekiel, however, is not speaking of postmortem judgment, with future reward and punishment, but of the collective future of the Judahite exiles.[6] Significantly, in contrast to Daniel, nowhere in the Ezekiel passage do we find mention of any specific eschatological event.

The Archaeology of Judahite Burial Customs

The detailed and poignant description of the bones’ appearance and how they come together reflects ancient Judean burial practices and beliefs during the first millennium B.C.E., where we see the use of subterranean tombs for communal interments.[7]

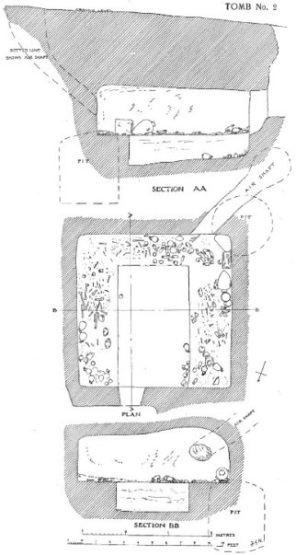

One type, the “Judahite rock-cut bench tomb,” consisted of chambers, cut out of rock, with three benches on the walls opposite the entrance, along with a pit which served as a repository for the bones of the decomposed bodies.

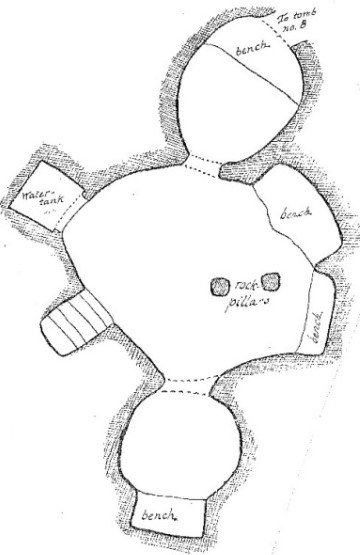

The other type, “loculus tombs,” are natural caves that have been augmented or expanded by carved out spaces along the walls.

|

|

|

Beth-Shemesh Tomb 2. Image from Duncan Mackenzie. Excavations at Ain Shems (Beth-Shemesh). (London: Palestine Exploration Fund, 1913), pl. V. |

Gezer Tomb 59. Image from R. A. S. Macalister. The Excavation of Gezer, 1902–1905 and 1907–1909. Vol. 3. (London: J. Murray, 1912), pl. LVI. |

Both types of tombs facilitated multiple burials, what archaeologists call communal interment, and were reused over time.[8] In tombs without pits, the bones were simply piled up in a corner.

The corpse was first placed in the supine position upon a bench carved out of the walls of the cave. Once the body decomposed, the skeleton was removed, and its disarticulated bones were stored in the tomb’s repository,[9] some of which preserved the remains of up to a hundred or more bodies.[10] This mass of undifferentiated bones that accumulated inside a family tomb, spanning multiple generations, represented the family’s collective ancestors, with whom newly deceased family members would join. (See addendum.)

Joseph’s Bones

The importance of keeping the bones in the family tomb is evident in several biblical accounts. For instance, Joseph makes his brothers swear an oath that they will bring his bones out of Egypt to the Promised Land:

בראשית נ:כה וַיַּשְׁבַּע יוֹסֵף אֶת בְּנֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל לֵאמֹר פָּקֹד יִפְקֹד אֱלֹהִים אֶתְכֶם וְהַעֲלִתֶם אֶת עַצְמֹתַי מִזֶּה.

Gen 50:25 So Joseph made the sons of Israel swear, saying, “When God has taken notice of you, you shall carry up my bones from here.”

The Israelites eventually fulfill this oath:

יהושע כד:לב וְאֶת עַצְמוֹת יוֹסֵף אֲשֶׁר הֶעֱלוּ בְנֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל מִמִּצְרַיִם קָבְרוּ בִשְׁכֶם בְּחֶלְקַת הַשָּׂדֶה אֲשֶׁר קָנָה יַעֲקֹב מֵאֵת בְּנֵי חֲמוֹר אֲבִי שְׁכֶם בְּמֵאָה קְשִׂיטָה וַיִּהְיוּ לִבְנֵי יוֹסֵף לְנַחֲלָה.

Josh 24:32 The bones of Joseph, which the Israelites had brought up from Egypt, were buried at Shechem in the piece of ground which Jacob had bought for a hundred kesitahs from the children of Hamor, Shechem’s father, and which had become a heritage of the Josephites.[11]

The burial of Joseph’s bones in Josephite territory reflects the connection between the people and their eponymous ancestor.

The Bones of Saul’s Family

Killed in battle with the Philistines, and then humiliated by having their bodies hung on the walls of Beit-sheʾan, Saul and Jonathan were buried at the foot of a tamarisk tree in Jabesh-gilead. Years later, after David has seven of Saul’s descendants executed to avoid YHWH’s wrathful vengeance against Israel on behalf of the Gibeonites, whom Saul slaughtered, all nine are buried in the family’s ancestral plot in Tzelah:

שמואל ב כא:יב וַיֵּלֶךְ דָּוִד וַיִּקַּח אֶת עַצְמוֹת שָׁאוּל וְאֶת עַצְמוֹת יְהוֹנָתָן בְּנוֹ מֵאֵת בַּעֲלֵי יָבֵישׁ גִּלְעָד אֲשֶׁר גָּנְבוּ אֹתָם מֵרְחֹב בֵּית שַׁן אֲשֶׁר (תלום שם הפלשתים) [תְּלָאוּם שָׁמָּה פְּלִשְׁתִּים] בְּיוֹם הַכּוֹת פְּלִשְׁתִּים אֶת שָׁאוּל בַּגִּלְבֹּעַ. כא:יג וַיַּעַל מִשָּׁם אֶת עַצְמוֹת שָׁאוּל וְאֶת עַצְמוֹת יְהוֹנָתָן בְּנוֹ וַיַּאַסְפוּ אֶת עַצְמוֹת הַמּוּקָעִים. כא:יד וַיִּקְבְּרוּ אֶת עַצְמוֹת שָׁאוּל וִיהוֹנָתָן בְּנוֹ בְּאֶרֶץ בִּנְיָמִן בְּצֵלָע בְּקֶבֶר קִישׁ אָבִיו...

2 Sam 21:12 And David went and took the bones of Saul and of his son Jonathan from the citizens of Jabesh-gilead, who had made off with them from the public square of Beit-sheʿan, where the Philistines had hung them up on the day the Philistines killed Saul at Gilboa. 21:13 He brought up the bones of Saul and of his son Jonathan from there; and he gathered the bones of those who had been impaled. 21:14 And they buried the bones of Saul and of his son Jonathan in Zela, in the territory of Benjamin, in the tomb of his father Kish….

Again, we see the importance of gathering the bones from all the various family members and placing them together in the family tomb.

Inverting the Repository

In Ezekiel’s vision, the valley filled with the collective remains of dry, disarticulated bones, symbolizes a repository of all of Israel, who find themselves now in exile. Indeed, Ezekiel’s vision may be subtly highlighting one of the key differences between Judean burials, which take place in a remote location outside the settlement, and that of Babylonians and Assyrians, who would maintain cemeteries inside the city walls, including house burials. In other words, in Mesopotamia, people would bury their family beneath the floors of their homes. This was disturbing enough to Judeans that the Temple Scroll, found in Qumran, specifically polemicizes against it:

מגילת המקדש מח:יא–יג ולוא תעשו כאשר הגויים עושים בכול מקום המה קוברים את מתיהמה וגם בתוך בתיהמה הם קוברים כי אם מקומות תבדילו בתוך ארצכמה אשר תהיו קוברים את מתיכמה.

Temple Scroll 48:11–13 So you may not do as the nations do; they bury their dead anywhere. They even bury (them) inside their houses. Rather, you shall set aside places within your land in which you shall bury your dead.[12]

Thus, Ezekiel may be subtly agreeing with his listeners that they are on foreign soil, where even burial practices are not in keeping with what Judeans practice at home. The vision of these bones coming back to life means that Israel will once again be a living community in their land. The vision draws on the ideological linking of bones, burial, and land, inverting the order of events to express a message of return.

The typical process of internment began with the placement of an individual corpse inside the tomb. In that setting the corpse would gradually decompose and the skeletal remains were disassembled and transferred to the tomb’s repository where the bones would join the collective bones of former burials. Ezekiel’s vision, in contrast, begins with a valley-wide repository filled with bones, and it ends with intact bodies of now-living peoples who are brought out of the tomb.

Ezekiel means to inform the Judean exiles that rather than dying in exile, and their national identities disappearing with their deaths and internment on foreign land, YHWH will restore their Judean national identities. In doing so, YHWH will once again grant them a covenantal future in the land of their inheritance.

Framing the Narrative with Resting/Placing (נ.ו.ח)

The vision of the valley of dry bones is framed by the verbal-root for “resting” or “placing” something—נ.ו.ח in the causative, hiphʿil form.

יחזקאל לז:א ...וַיְנִיחֵנִי בְּתוֹךְ הַבִּקְעָה וְהִיא מְלֵאָה עֲצָמוֹת.

Ezek 37:1 …and he set me down in the valley. It was full of bones.

לז:יד וְנָתַתִּי רוּחִי בָכֶם וִחְיִיתֶם וְהִנַּחְתִּי אֶתְכֶם עַל אַדְמַתְכֶם...

37:14 I will put My breath into you and you shall live again, and I will set you upon your own soil…

The verb is evocative of the promises that are found in Deuteronomy and Joshua, where YHWH speaks of giving the Israelites rest from their oppressors in the land of their inheritance.[13] For example, in, Moses says that the law requiring Israel to destroy Amalek only takes effect after the Israelites have defeated their other enemies:

דברים כה:יט וְהָיָה בְּהָנִיחַ יְ־הוָה אֱלֹהֶיךָ לְךָ מִכָּל אֹיְבֶיךָ מִסָּבִיב בָּאָרֶץ אֲשֶׁר יְ־הוָה אֱלֹהֶיךָ נֹתֵן לְךָ נַחֲלָה לְרִשְׁתָּהּ...

Deut 25:19 Therefore when YHWH your God has given you rest from all your enemies on every hand, in the land that YHWH your God is giving you as an inheritance to possess…[14]

The same verb הניח appears in a story in Kings describing the death of a prophet who sins, and is mauled by a lion. Another prophet, who had hosted him brings his dead body home and buries it in his own family plot, as he wants their bones to mix in the future:

מלכים א יג:כט וַיִּשָּׂא הַנָּבִיא אֶת נִבְלַת אִישׁ הָאֱלֹהִים וַיַּנִּחֵהוּ אֶל הַחֲמוֹר וַיְשִׁיבֵהוּ וַיָּבֹא אֶל עִיר הַנָּבִיא הַזָּקֵן לִסְפֹּד וּלְקָבְרוֹ. יג:ל וַיַּנַּח אֶת נִבְלָתוֹ בְּקִבְרוֹ וַיִּסְפְּדוּ עָלָיו הוֹי אָחִי. יג:לא וַיְהִי אַחֲרֵי קָבְרוֹ אֹתוֹ וַיֹּאמֶר אֶל בָּנָיו לֵאמֹר בְּמוֹתִי וּקְבַרְתֶּם אֹתִי בַּקֶּבֶר אֲשֶׁר אִישׁ הָאֱלֹהִים קָבוּר בּוֹ אֵצֶל עַצְמֹתָיו הַנִּיחוּ אֶת עַצְמֹתָי.

1 Kgs 13:29 The prophet lifted up the corpse of the man of God, set it on the donkey, and brought it back; it was brought to the town of the old prophet for lamentation and burial. 13:30 He set the corpse in his own burial place; and they lamented over it, “Alas, my brother!” 13:31 After burying him, he said to his sons, “When I die, bury me in the grave where the man of God lies buried; rest[15] my bones beside his bones.”[16]

In Ezekiel’s vision, YHWH sets/places (וַיְנִיחֵנִי) Ezekiel in the valley where he can see the bones and what will happen with them: YHWH promises to place (וְהִנַּחְתִּי) the Israelites again in their native land. Thus, YHWH tells Ezekiel, the Judean exiles are not being left in the tomb of exile. Instead, their burial places will be opened, their repositories emptied, and their bones will be reassembled into a community who are restored to their ancestral land once again.[17] As Ezekiel prophesized:

יחזקאל לז:יב ...כֹּה אָמַר אֲדֹנָי יְ־הוִה הִנֵּה אֲנִי פֹתֵחַ אֶת קִבְרוֹתֵיכֶם וְהַעֲלֵיתִי אֶתְכֶם מִקִּבְרוֹתֵיכֶם עַמִּי וְהֵבֵאתִי אֶתְכֶם אֶל אַדְמַת יִשְׂרָאֵל.

Ezek 37:12 …Thus said the Sovereign YHWH: ‘I am going to open your tombs and lift you out of the tombs, O My people, and bring you to Israel’s soil.’

Addendum

The Importance of Being Buried in Family Tombs

The Bible emphasizes the importance of being buried in one’s family tomb, reunited with one’s ancestors.[18] For example:

The Cave of Machpelah and the Patriarchs

Since Abraham moves to Canaan from Mesopotamia, he must establish for his family its own tomb upon the death of his wife, Sarah. Genesis dedicates all of chapter 23 to this transaction. Abraham wants to ensure that his family owns this plot for posterity, as opposed to using land from another family.

Later, when Jacob is on his deathbed in Egypt, he tells his sons that his body should be buried in the Land of Canaan, not Egypt, so that he can be buried with his ancestors in the Cave of Machpelah:

בראשית מט:כט ...אֲנִי נֶאֱסָף אֶל עַמִּי קִבְרוּ אֹתִי אֶל אֲבֹתָי אֶל הַמְּעָרָה אֲשֶׁר בִּשְׂדֵה עֶפְרוֹן הַחִתִּי... מט:לא שָׁמָּה קָבְרוּ אֶת אַבְרָהָם וְאֵת שָׂרָה אִשְׁתּוֹ שָׁמָּה קָבְרוּ אֶת יִצְחָק וְאֵת רִבְקָה אִשְׁתּוֹ וְשָׁמָּה קָבַרְתִּי אֶת לֵאָה.

Gen 49:29 I am about to be gathered to my kin. Bury me with my fathers in the cave which is in the field of Ephron the Hittite… 49:31 there Abraham and his wife Sarah were buried; there Isaac and his wife Rebecca were buried; and there I buried Leah…

The Cave of Machpelah thus serves as a family burial site for three generations. Indeed, the biblical expression “gathered to my kin”—like the similar expression וַיִּשְׁכַּב עִם אֲבֹתָיו “he lay down with his fathers,” the standard phrase for the death of an Israelite king[19]—expresses the translation of the individual into a collective, family identity.

Nehemiah’s Worries about His Family Tombs

Nehemiah, described as having been Artaxerxes (I)’s wine steward, enters the king’s presence looking sad, leading the king to ask him why.

נחמיה ב:ג וָאֹמַר לַמֶּלֶךְ הַמֶּלֶךְ לְעוֹלָם יִחְיֶה מַדּוּעַ לֹא יֵרְעוּ פָנַי אֲשֶׁר הָעִיר בֵּית קִבְרוֹת אֲבֹתַי חֲרֵבָה וּשְׁעָרֶיהָ אֻכְּלוּ בָאֵשׁ.

Neh 2:3 And I answered the king, “May the king live forever! How should I not look bad when the city of the graveyard of my ancestors lies in ruins, and its gates have been consumed by fire?”

Nehemiah expresses his concerns not merely about the city, but about the condition of his ancestral tombs. The king is sympathetic, asking what he can do, and Nehemiah’s answer again emphasizes the family tombs:

נחמיה ב:ה וָאֹמַר לַמֶּלֶךְ אִם עַל הַמֶּלֶךְ טוֹב וְאִם יִיטַב עַבְדְּךָ לְפָנֶיךָ אֲשֶׁר תִּשְׁלָחֵנִי אֶל יְהוּדָה אֶל עִיר קִבְרוֹת אֲבֹתַי וְאֶבְנֶנָּה.

Neh 2:5 I answered the king, “If it please the king, and if your servant has found favor with you, send me to Judah, to the city of my ancestors’ graves, to rebuild it.”

Despite Nehemiah living in exile, he is concerned about his family’s ancestral tomb in Judea and wishes to ensure it is protected.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

July 19, 2024

|

Last Updated

December 21, 2025

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Prof. Matthew J. Suriano is an Associate Professor in the Joseph and Rebecca Meyerhoff Center for Jewish Studies at the University of Maryland where he teaches Hebrew Bible, ancient religions, and archaeology. His Ph.D. is from UCLA and he has an M.A. from Jerusalem University College. He was also a visiting graduate student at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem. A former fellow at the W.F. Albright Institute of Archaeological Research in Jerusalem, Suriano has participated in several archaeological excavations and surveys in Israel, most recently at Tel Burna where he was a member of the research staff. He has written extensively on death and burial in the ancient world, starting with his first book Politics of Dead Kings (Mohr Siebeck, 2010), which is a revised version of his dissertation. His second book, A History of Death in the Hebrew Bible (Oxford University Press, 2018), won the American Society for Overseas Research’s Frank Moore Cross Award.

Essays on Related Topics: