Edit article

Edit articleSeries

Louis Jacobs: We Have Reason to Believe

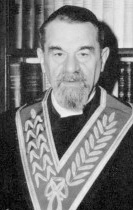

Photo courtesy of The Louis Jacobs Foundation

Traditional Beginnings

Louis Jacobs (1920-2006) was born in Manchester, England to an observant, working-class family.[1] His early Jewish education was very traditional—he studied at both the Manchester and the Gateshead Yeshivahs, which represented the Ultra-Orthodox (haredi), Eastern European world. He was ordained in 1943 by R. Menachem Tzvi Rivkin (1869–1948), head of the Manchester Beth Din (rabbinical court). Desiring to serve as a congregational rabbi, he went to study at Jews’ College in London.

London: The Clash Between Jews’ College and University College

Students at Jews’ College, which offered traditional, Orthodox rabbinic ordination, also studied at University College London, where Jacobs studied Semitics—alongside Greek and Latin—and concentrated on rabbinic literature.[2] In his autobiography, Jacobs often speaks of the contrast between the traditional approach of Jews’ College, more in line with his training in Manchester and Gateshead (though Jews’ College was less intensive and somewhat more liberal than Gateshead and Manchester), and the critical, academic approaches to all of Jewish literature at University College.[3]

A Young Rabbi

Jacobs briefly assisted R. Dr. Eliyahu Munk (1900–1978) at the Golders Green Beth Hamedrash in London from 1945, and served as rabbi in the Central Synagogue in Manchester from 1948. In 1954, Jacobs became the rabbi at the New West End Synagogue. While this congregation was affiliated with the United Synagogue, the main Orthodox umbrella organization in Great Britain, it was not the typical United Synagogue institution.

According to Jacobs, New West End Synagogue represented “tolerance, broadmindedness and love of tradition,”[4] and its membership was comprised of the more acculturated but still traditional London Jewish population, including many of its leaders. There and elsewhere he taught and lectured broadly, developing and sharing the ideas that would eventually be published in his controversial 1957 book.

We Have Reason to Believe: Introducing Liberal Supernaturalism

We Have Reason to Believe is a powerful and broad argument for continuing traditional Judaism, anchored in contemporaneous scholarship of Judaism. It was popular and influential, appearing in five editions between 1957 and 2004. (Jacobs was a clear and passionate writer, and this book is still well-worth reading in its entirety.)

Two of its chapters—“The Torah and Modern Criticism” and “A Synthesis of the Traditional and Critical Views”—concern revelation, a topic which he recognized was challenging to many contemporary Jews struggling between traditional faith and modern notions of history and religion:

The confidence of many people in the Bible as the Word of God has been shaken by modern critical investigations so that no work of Jewish apologetics, however limited in scope, can afford to fight shy of the problem…[5]

To talk about ‘reconciling’ the Maimonidean idea and the Documentary Hypothesis (or, for that matter, any other view based on ‘untraditional’ methods of investigation) is futile for you cannot reconcile two contradictory theories. But to say this is not to preclude the possibility of a synthesis between the old and new knowledge. There is a clear distinction between saying that two points of view are both correct and saying that they both contain truth.[6]

It is in these chapters that Jacobs first articulates a position he calls liberal supernaturalism, which insists that the revelation at Sinai was a real event, but the Torah as we now have it is not identical to the product of that revelation, a position with significant parallels among some contemporaneous Protestant theologians:[7]

No doubt our new attitude to the Biblical record, in which, as the result of historical, literary and archaeological investigations, the Bible is seen against the background of the times in which its various books were written, ascribes more to the human element than the ancients would have done, but this is a difference in degree, not in kind. The new knowledge need not in any way affect our reverence for the Bible and our loyalty to its teachings. God’s Power is not lessened because He preferred to co-operate with His creatures in producing the Book of Books.[8]

Jacobs dealt not only with large issues such as these, but even delved into nitty-gritty problems such as imperfections or textual corruptions in the Masoretic text, which must be emended to be understood properly.[9] Why Jacobs went ahead in publishing such a controversial work at this point in his career, when he was hoping to play a leadership role in the Orthodox Jewish community, is unclear, but as we shall see, the work had an adverse effect on these plans.

Lecturer at Jews’ College

Jacobs left the pulpit in 1959 to become Moral Tutor and Lecturer in Pastoral Theology in Jews’ College, with the understanding that he would be appointed its Principal [=head] upon the retirement of Rabbi Ezekiel Isidore Epstein (1894–1962). Epstein was a religiously conservative scholar of rabbinics, best known as the editor of the Soncino Talmud.[10]

Jacobs represented a different kind of traditional Judaism, and for the lay leadership of Jews’ College and Jacobs’s supporters at large, he offered an open-minded traditionalism. Chief Rabbi Israel Brodie (1895–1979) approved Jacobs’s appointment as lecturer,[11] even though both he and the London Beth Din, the somewhat independent and conservative rabbinic court of the United Synagogue, may have been wary of Jacobs.

The Jacobs Affair: Part One

By late autumn of 1961, it became apparent that Brodie would not allow Jacobs to assume the position of Principal. This marks the beginning of what came to be known as the Jacobs Affair.[12] It is unclear whether Brodie changed his mind about Jacobs, or if he never really meant to allow him to take the reins of the institution (and perhaps afterward, chief rabbi), but whatever the explanation, the matter became public and contentious.

In 1962, the Beth Din defended Brodie, stating that “some of the views expressed in recent years in publications and articles by [Jacobs] are in conflict with authentic Jewish beliefs,” but the dayanim [= members of the court] and Brodie studiously avoided specifying or explaining their objections.[13] Perhaps they felt that by mentioning the book, they would publicize it further, or perhaps issues other than the publication of the book stood behind their objections to Jacobs. But even if that is the case, Jacobs’s theology certainly played some role.

Jacobs was swimming against the tide of the accepted positions of traditional Anglo rabbis concerning the origin of the Torah, especially the position so emphatically promoted by Rabbi Joseph Hertz, in his The Pentateuch and Haftorahs (pub. 1929–1936). This volume, which became available in a convenient one-volume edition in 1937, aimed at presenting a modern and cosmopolitan feel by quoting contemporary scholars, even non-Jews.

It also contained forceful mini-essays at the end of each biblical book that staunchly defended traditional views of the Torah against Higher Criticism (source criticism).[14] Hertz was well-respected as a former chief rabbi, and his royal blue Pentateuch had near-canonical status in the synagogue pews. What Jacobs had to say challenged the traditional position that it so powerfully represented.

The Jacobs Affair Part Two: The Sanction for the Mitzwoth

Meanwhile, Jacobs’s replacement at the New West End Synagogue left for the United States, and Jacobs, to the delight of many members of the congregation, sought to return. But the chief rabbi had to approve all rabbinic appointments in the United Synagogue, and Brodie, without any explanation, refused to approve Jacobs’ (re)appointment. This further exacerbated the public affair, leading to what scholars call part two of the Jacobs Affair.

Amidst this turmoil, Jacobs founded the Society for the Study of Jewish Theology, where in 1963 he offered a lecture, also published in a pamphlet, called “The Sanction for the Mitzwoth.”[15] In this very public forum, he proclaimed:

Suffice it to say that as a result of the devoted researches of a host of distinguished scholars and thinkers over the past one hundred and fifty years a new picture has emerged concerning the nature of the Biblical record and the Rabbinic interpretation of it. According to this picture the Bible is still the source of our faith and religion. It is still the world-transforming word of God. But it is now seen that the Bible is not, as the mediaeval Jew thought it was, a book dictated by God but a collection of books which grew gradually over the centuries and that it contains a human as well as a divine element.

This applies to the Pentateuch as well as to the rest of the Bible.[16] …The result has been that thinking men have tried valiantly to reinterpret a faith based on the idea of Revelation so that it is in accord with the new facts.

This is a sharp, concise, and unambiguous summary of his view of revelation articulated in We Have Reason to Believe.

Only in 1964, after Jacobs founded the New London Synagogue, conceived of as an “independent orthodox congregation,”[17] and offered his lecture on “The Sanction for the Mitzwoth,” did Brodie explicitly justify his actions on the basis of Jacobs’s ideas regarding the Bible. Why Brodie publicly justified his decision only then is unclear—Jacobs had given him a copy of We Have Reason to Believe when it was published in 1957!

Brodie offered his reasoning at a meeting of rabbis and ministers of the Anglo-Jewish community on May 5, 1964, in a statement also printed in The Jewish Chronicle, the British Jewish newspaper of record.[18] There, Brodie excoriates Jacobs, claiming:

But Dr. Jacobs repeats the well-worn thesis that parts of the Torah are not Divine but are man made, and maintains that reason alone should be the final judge as to what portion of the Torah may be selected as Divine.

After citing the Sanction of the Mitzvoth [sic.], he states:

An attitude to the Torah such as this which denies its Divine source and unity (Torah min Hashamayim) is directly opposed to orthodox teaching, and no person holding such views can expect to obtain approval of the orthodox Ecclesiastical authority.

Brodie goes on by quoting Epstein, whom Jacobs had hoped to replace as Principal of Jews’ College, concerning “The fatal and inherent weakness of those who deny the Divine origin of the Bible.” Epstein claims of such people: “By favourite tricks they play with the Bible, which they regard as partly Divine and partly human….” In a rhetorical flourish, Brodie concludes with Deuteronomy 4:44: “This is the law which Moses put before the Children of Israel.”[19]

The Reasons for the Affair

It took Brodie three years to clarify his objections to Jacobs, and when these were made explicit, theological issues are front and center, and the Affair is now remembered in these terms. But it is unclear if the theological debate concerning revelation is the only or main factor that lies at the base of the Jacobs’s Affair, or if it was only understood to be the precipitating factor in retrospect.[20]

Personality issues may have been a factor; some point to Brodie’s reactive and fearful personality, others to Jacobs’s naivete in raising the issue of biblical criticism so publicly. Other factors may also have contributed to the Affair: a basic theological dispute as to whether Judaism contains dogmas, Jacobs’ connections to several leaders at the Jewish Theological Seminary, and Jacobs’ lack of understanding of the extent to which the New West End Synagogue was an outlier within British synagogues.

The Affair should also be understood more broadly in relation to other contemporaneous issues occupying British Jewry concerning the Bible, especially a lecture sponsored by the Oxford Hillel Foundation by the poet, classics scholar, and scholar of myth, Robert Graves, to over a thousand attendees at Oxford in fall 1961, in which he discussed the Bible as myth. This lecture, which brought critical attitudes to the Bible to public attention, was roundly condemned by many leading rabbis.[21]

Above and beyond these factors, the later perception, especially after Brodie’s 1964 statement, is that that the core issue was Jacobs’s ideas as expressed in We Have Reason to Believe, centering on the significance and meaning of Torah min HaShamayim, the divine origin of the Torah (literally: Torah from heaven). This Affair brought the matter of traditional and more modern views of revelation into the limelight for the broader English-reading public.[22] It riveted British Jewry in the 1960s and was covered very extensively in The Jewish Chronicle (the main British Jewish weekly), whose editor sided with Jacobs and stirred things up. In part because it paralleled contemporaneous Christian debates,[23] it was also discussed in the broader British press, and even beyond.

Further Developments of Liberal Supernaturalism

Jacobs defended and developed his position throughout his life.

Principles of the Jewish Faith

In his 1964 examination of the thirteen principles of faith of Maimonides, Principles of the Jewish Faith: An Analytical Study,[24] Jacobs spends more time on Maimonides’s eighth principle concerning the divine revelation of the Torah than on any other, and writes:

[P]ainful though the process is, the modern Jewish believer is obliged to reinterpret the whole idea of revelation. But to reinterpret does not mean to abandon.[25]

This book shows a serious and remarkably broad knowledge of, and engagement with, contemporaneous academic biblical studies that is rarely seen in rabbis without professional training in it; most rabbis who polemicize against academic biblical scholarship have little first-hand acquaintance with it. Jacobs claims there that “Fundamentalism and the doctrine of verbal inspiration have been widely discredited” and advocates a “scientific approach” to the Bible.

Going beyond his 1957 claims, which were relatively tame, he notes that the Documentary Hypothesis “is a work of extraordinary genius” and that Wellhausen’s historical reconstruction has some problems, but “is endowed with a high degree of plausibility.”[26] His discussion of both Higher and Lower Criticism in this book is not original, but shows a deep understanding of, and much sympathy for, these methods.

Beyond Reasonable Doubt

In his 1999 Beyond Reasonable Doubt, presented as a sequel to his 1957 book, Jacobs returns to these issues, noting unapologetically and much more stridently than in his earlier work:

To turn to scholarly investigations of the Torah itself, it can immediately be seen that the two propositions that the Torah was given at one time by God to Moses and that the Torah is infallible even when it speaks of historical events and the nature of the physical world, are simply untenable. It has been established beyond a reasonable doubt that the Pentateuch is a heterogeneous or composite work….[27]

Throughout the book, Jacobs emphasizes how his introduction to the historical study of Judaism helped him develop this theology.[28]

The Continued Importance of the Affair

The Jacobs Affair lasted well beyond the early 1960s. For example, in 1984, Jacobs debated these issues on the pages of the Jewish Chronicle with the then Chief Rabbi Jonathan Sacks.[29] Jacobs’s work is often cited in contemporary discussions of a slowly developing tolerance for biblical criticism in the Orthodox world.[30]

A Lifelong Attempt at Reconciling Tradition and Scholarship

Jacobs was an extremely prolific author, writing many original articles on rabbinics, hasidism, and theology, and many synthetic books in the range of Jewish Studies,[31] and his importance far exceeded the public controversy for which he is best known. In a 2005 poll in The Jewish Chronicle, he was voted as the greatest British Jew of all time.[32] Upon his death, the obituary by the rabbi of the New North London Synagogue, which Jacobs founded, noted:

His books, covering in some forty volumes almost every sphere of rabbinic scholarship, will make him the teacher of many generations to come. With an utter commitment to the truth, he was unbending in his integrity and no amount of communal politics, or condemnation or branding, could deter him from the quest.[33]

Jacobs spent his adult life trying to reconcile his two titles of Dr. and Rabbi, but was not entirely successful; as noted by Elliot Cosgrove, the rabbi of New York’s Park Ave. Synagogue and an expert on Louis Jacobs:

His struggles between faith and reason, observance and critical scholarship, reflect a lifetime effort to reconcile the competing, contradictory and often insoluble commitments of the first half of his life. To the very end, Jacobs remained a bifurcated soul, forever loyal to the range of traditions embedded within him.[34]

Jacobs stands as a model for honesty and integrity in trying to integrate traditional Jewish practice with ever-changing scholarship, and it is our pleasure to contribute this piece to recognize his upcoming hundredth birthday.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

June 15, 2020

|

Last Updated

January 5, 2026

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Prof. Marc Zvi Brettler is Bernice & Morton Lerner Distinguished Professor of Judaic Studies at Duke University, Dora Golding Professor of Biblical Studies (Emeritus) at Brandeis University, and a research professor at Hebrew University. He is author of many books and articles, including How to Read the Jewish Bible (also published in Hebrew), co-editor of The Jewish Study Bible and The Jewish Annotated New Testament (with Amy-Jill Levine), and co-author of The Bible and the Believer (with Peter Enns and Daniel J. Harrington), and The Bible With and Without Jesus: How Jews and Christians Read the Same Stories Differently (with Amy-Jill Levine). Brettler is a cofounder of TheTorah.com.

Prof. Edward Breuer is a native of Montreal Canada and received his Ph.D. from Harvard; he currently teaches at the Hebrew University. Breuer writes about the history of biblical scholarship in the modern era, and is the co-author with Chanan Gafni of “Jewish Biblical Scholarship between Tradition and Innovation” and, with David Sorkin, Moses Mendelssohn's Hebrew Writings (Yale, 2018).

Essays on Related Topics: