Edit article

Edit articleSeries

Mordechai Rides King Ahasuerus’ Horse, but Who Wears the Crown?

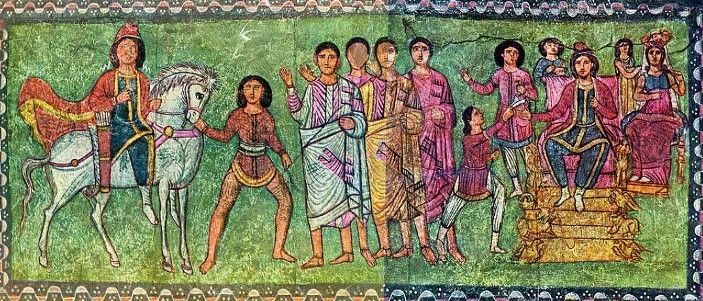

Mordecai’s Triumph (adapted), James Tissot, c. 1896-1902. The Jewish Museum

On a sleepless night, King Ahasuerus discovers that Mordechai, the Jew, has never been acknowledged for revealing a plot against the king’s life, and he decides to correct the oversight. At that moment, his official, Haman, enters the courtyard to seek royal permission to hang Mordechai. Without explaining, the king seeks Haman’s advice:

אסתר ו:ו וַיָּבוֹא הָמָן וַיֹּאמֶר לוֹ הַמֶּלֶךְ מַה לַעֲשׂוֹת בָּאִישׁ אֲשֶׁר הַמֶּלֶךְ חָפֵץ בִּיקָרוֹ וַיֹּאמֶר הָמָן בְּלִבּוֹ לְמִי יַחְפֹּץ הַמֶּלֶךְ לַעֲשׂוֹת יְקָר יוֹתֵר מִמֶּנִּי.

Esth 6:6 Haman entered, and the king asked him, “What should be done for a man whom the king desires to honor?” Haman said to himself, “Whom would the king desire to honor more than me?”

Mistakenly thinking that the king means to honor him, Haman first advises Ahasuerus to bestow upon the honoree a garment and horse that the king has used:

אסתר ו:ח יָבִיאוּ לְבוּשׁ מַלְכוּת אֲשֶׁר לָבַשׁ בּוֹ הַמֶּלֶךְ וְסוּס אֲשֶׁר רָכַב עָלָיו הַמֶּלֶךְ וַאֲשֶׁר נִתַּן כֶּתֶר מַלְכוּת בְּרֹאשׁוֹ.

Esth 6:8 Let them bring a royal garment that the king has clothed himself in it, and a horse that the king has ridden on it and that a royal crown has been placed on his head.

His final comment, however—shown in bold—is ambiguous. Grammatically, the phrase cannot refer to the honoree himself,[1] but to whom or what does the relative pronoun וַאֲשֶׁר (vaʾ-asher), “and that,” refer, and on whose head has the crown been placed?

The King

A common solution is to interpret the phrase as referring to the king’s coronation. For example, R. Joseph ben Joseph ibn Nachmias (14th century, Toledo) reads וַאֲשֶׁר as though it were כַּאֲשֶׁר (ka-ʾasher), and understands the phrase as “when the crown was placed upon his head.” He writes:

והנכון בעיני, שו״ו ואשר במקום כ״ף, ורוצה לומר: וסוס אשר רכב עליו המלך כאשר נתן כתר מלכות בראשו, כלומר: ביום שמלך. והתרגום מסייעני.

And it is correct in my opinion that khaf be [read] in the place of vav in ואשר, and it intends to say: “and a horse on which the king rode when a royal crown was put on his head,” that is: on the day he became king. And the Targum [Aramaic translation] helps me…

Nachmias quotes the First Targum to Esther (dated to c. 500–700 C.E.),[2] which adds the words “on the day that he ascended to the kingship” to the passage in the descriptions of the garment and horse:

יָשִׂים מַלְכָּא טְעֵם יַיְתוּן לְבוּשׁ אַרְגְוָנָא דִי לְבִישׁוּ בֵיהּ יַת מַלְכָּא בְּיוֹמָא דִי עַל לְמַלְכוּתָא וְסוּסָא דִי רְכַב עֲלוֹי מַלְכָּא בְיוֹמָא דְעַל לְמַלְכוּתָא וְדִי אִתְיְהֵב כְּלִילָא דְמַלְכוּתָא בְּרֵישֵׁיהּ.

Let the king make a decree: let them bring purple clothing in which they dressed the king on the day that he ascended to the kingship and the horse that the king rode upon it on the day that he ascended to the kingship, and that the crown of kingship was placed on his head.

Nachmias buttresses his interpretation by noting another biblical verse in which a vav should be understood as though it were a khaf:

ומצאתי כתוב אומר: כי אזן מילין תבחן וחיך יטעם לאכול (איוב ל״ד:ג׳) משפטו: כחיך יטעם לאכול.

And I found a verse that says: “For the ear tries words and the palate tastes food” (Job 34:3). Its proper meaning is: As the palate tastes food.

The Coronation Crown Was Bestowed on the Honoree

R. Joseph Kara (ca. 1050–1130, Troyes) argues that the crown that the king wore at his coronation is also bestowed upon the honoree:

יביאו לבוש מלכות – לבושא של מלכות היה לו למלך שלא לבש כי אם באותו יום שהועמד למלכות, וכן סוס שרכב עליו המלך, וכן כתר המלוכה, אשר ניתן כתר מלכות בראשו – של מלך ביום שעמד למלוך.

“Let them bring royal clothing.” – The king had royal clothing that he wore only on that specific day when he was crowned, and so too a horse that the king rode upon, and so too the royal crown, that the royal crown was placed on his head—of the king, on the day that he was crowned.[3]

Kara’s understanding that Haman includes the royal crown may be built on a midrashic reading that Haman desires kingship for himself. For example, in Pirqe Rabbi Eliezer 50 (ca. 8th–9th c. C.E.), Haman’s request angers Ahasuerus:

וכעס המלך על הכתר הרבה מאד, אמר המלך הרשע הזה לא דיו שאמר אלי על המלבוש ועל הסוס אלא אף על הכתר שבראשי, אם כן מה הניח לי?

The king was exceedingly angry because of the crown. The king said: “It is not enough for this villain that he speaks to me about the garment and about the horse, but also about the crown which is upon my head. If so, what remains for me?”

Noticing the king’s anger, Haman does not mention the crown again:

כיון שראה המן שכעס המלך על הכתר, חזר ואמר ונתון הלבוש והסוס על יד איש משרי המלך הפרתמים [אסתר ו:ט].

When Haman saw that the king was angry because of the crown, he said: “And let the garment and the horse be put in the charge of one of the king’s noble courtiers” [Esth 6:9].

This explains why the crown is not included among the items bestowed on Mordecai in the story (v. 11).[4]

The Horse

An alternative way of interpreting this verse, one that better suits the actual grammar and words of the text, suggests an unexpected scenario: that the horse wears the crown.[5] This approach is preferred by R. Abraham ibn Ezra (c. 1088–1167), who claims that the custom of placing crowns on royal horses is “well-known”:

והנכון בעיני שוי״ו בראשו שב אל הסוס כי יש סוס של המלך שישימו כתר מלכות בראשו כאשר ירכב עליו, ואין אחד מעבדי המלך רשאי לרכוב עליו. וזה דבר ידוע.

And what is correct in my view is that the vav of “on his head” בראשו refers to the “horse,”[6] because there is a horse of the king upon whose head they would place a royal crown when he would ride on it, and none of the king’s servants would be allowed to ride upon it. And this is a known thing.

Ibn Ezra also rejects the idea that the text is disordered:

ור׳ מרינוס אמר: שהמלות הפוכות, והנכון: וכתר המלכות אשר נתן בראשו. והנכון בעיני שאיננו הפוך.

Rabbi Marinus (Jonah ibn Janah) said that the words [ואשר ניתן כתר מלכות בראשו] are out of order, and the correct order would be [וכתר מלכות אשר ניתן בראשו] (“and the royal crown which was placed on his head”). What is correct in my view is that it is not out of order.

He characterizes his own interpretation as peshat, and he offers an alternative explanation for the biblical text’s silence about the crown later in the narrative:

וככה פירושו שירכיבהו על סוס ידוע שרכב עליו המלך ונתן על ראש הסוס כתר מלכות על כן לא הזכיר הכתר במעשה, כי יספיק זכר הסוס הנודע, כי ככה מנהג מלכי פרס. והעד שאמר לו המלך אל תפל דבר מכל אשר דברת (אסתר ו׳:י׳), א״כ למה יחסר הכתר.

Its meaning is: that they shall lead him on a horse widely known as the horse upon which the king rides, and that the royal crown was placed upon the head of the horse. It is for this reason that Scripture does not mention the crown when telling us that Mordecai was seated on the royal horse, for mentioning the known horse alone was sufficient given that it was the practice of the Persian kings [to place a royal crown on the head of the horse upon which the king rides.] Textual evidence (והעד) is that the king said to him “let nothing fail of all that thou hast spoken” (Esth 6:10). Then, why would he omit the crown?[7]

Ancient and Modern Illustrations

The 3rd century C.E. wall painting from Dura Europos Synagogue shows an early interpretation of this scene in Esther.[8] The horse’s mane seems coiffed, but it is Mordecai who seems to be wearing distinctive headgear—likely a crown of sorts.

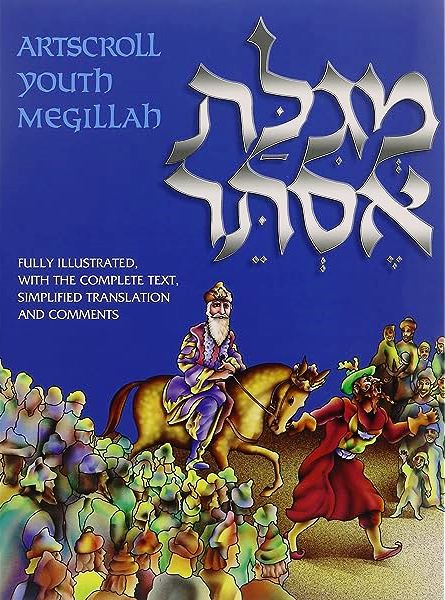

The idea that the horse was crowned has captured the fancy of some contemporary readers and illustrators and is common in modern critical commentaries. Biblical scholar Lewis Bayles Paton writes: “On whose head can only refer to the horse” (International Critical Commentary Series, 1908).[9]

More recent commentaries from Carey A. Moore (Anchor Bible, 1971), A. D. Cohen (Soncino Books of the Bible, 1971) and Jon D. Levenson (Old Testament Library, 1997) offer similar interpretations.[10] The idea also appears in the artwork on the cover of the ArtScroll illustrated children’s Megillah (1988)[11] and in the Koren Tanakh Graphic Novel (2023).[12]

|

|

Esth 6:8 Let royal garb which the king has worn be brought, and a horse on which the king has ridden, and on whose head a royal diadem has been set.

Royal Persian Horses in Visual Art

Some modern commentators have sought corroborating evidence for ibn Ezra’s claim that it was “known” that Persian kings placed crowns on the king’s horse in ancient images of royal Persian horses, most commonly referring to King Xerxes’ palace at Persepolis:[13]

|

|

| Stone relief of a Chorasnian with his horse. Apadana at Persepolis, East stairway.[14] | An image from Persepolis depicts a horse drawing a chariot:[15] |

In addition, an image of a Persian horseman on a felt saddlecloth from Pazyrik from the 5th century B.C.E. shows the horse wearing an ornate headdress:[16]

Biblical scholar Adele Berlin (University of Maryland), however, suggests that these images have been misinterpreted:

Fox mentions that Assyrian reliefs show the king’s horses wearing tall head ornaments. Moore refers to reliefs in Xerxes’ apadana at Persepolis, which, according to him, show horses with crowns. Actually, though, the crowns seem to be formed from a tuft of the horse’s hair tied in a band and sticking up like a crown.[17]

Ambiguities Can Lead to New Insights

Ambiguities in biblical texts can often feel like frustrating obstacles to comprehension, thwarting our efforts to uncover the “correct” meaning of the text. From another perspective, textual ambiguities can be seen as fertile ground for exegetical productivity, generating opportunities to study the history of textual interpretation.

Paying close attention to possible alternative meanings can open up avenues of interpretation that might not be obvious at first. This is true about the meaning of individual words, and also about the arrangement of larger units of words—the syntactic structure of a verse. Esther 6:8 is a fun example of how careful attention to syntax can be eye-opening.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

November 1, 2023

|

Last Updated

November 18, 2025

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Dr. Shani Tzoref is currently a Visiting Professor at the Hochschule für Jüdische Studien Heidelberg. Her previous positions include Chair of Hebrew Bible and Exegesis at the University of Potsdam and coordinator of the Biblical Studies program at the University of Sydney. Tzoref holds an M.A. in Jewish History from Yeshiva University and a Ph.D. in Ancient Jewish Literature from New York University, and is pursuing an additional M.A. in Digital Humanities from the CUNY Graduate center. She is the author of The Pesher Nahum Scroll from Qumran: An Exegetical Study of 4Q169.

Essays on Related Topics: