Edit article

Edit articleSeries

North Israelite Memories of the Transjordan and the Mesha Inscription

Map of the Transjordan

The Land of Moab in the Transjordan is a unique laboratory for studying materials in the Bible that portray historical realities of the Iron Age, the time of the two Hebrew kingdoms of Israel and Judah. Three converging sources make it possible to reconstruct several moments in the history of Israel and Moab:

- Biblical: The relatively detailed geographical references in the Bible, such as Heshbon, Dibon, Yahatz, Atarot, Aroer, Ar, Nebo, and the Arnon stream, that are securely identified;

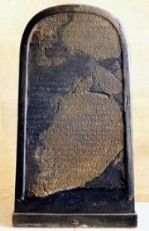

- Extra-biblical: The exceptional information contained in the Mesha Inscription, a stele found 1868 at the site of biblical Dibon;

- Archaeological: The well-preserved Iron Age sites in the region.

The War of Israel and King Mesha of Moab

The Mesha Stele is a royal inscription, written in autobiographical style from Mesha king of Moab, describing how Israel (the Northern Kingdom) conquered land in the Transjordan—what the Bible calls the mishor, “the flat land”[1]—and how Mesha eventually won it back:

עָמְרִי מֶלֶך יִשְׂרָאֵל, וַיְעַנוּ אֶת מֹאָב יָמִן רַבִּן, כִּי יֶאֱנַף כּמֹשׁ בְּאַרְצֹה. וַיַחֲלִיפֹה בְּנֹה וַיֹאמֶר גַם הֻא: אֲעַנֵו אֶת מֹאָב. בְּיָמַי אָמַר כֵּ[ן]. וַאֵרֶא בֹּה וֻבְּבֵתֹה. וְיִשְׂרָאֵל אָבֹד אָבַד עֹלָם. וַיִרַשׁ עֹמְרִי אֶת אֶרֶץ מְהֵדְבָא, וַיֵשֶׁב בָּה יָמֵהֻ וַחֲצִי יְמֵי בְּנֹה אַרְבָּעִן שָׁת, וַיְשִׁבֶהָ כּמֹשׁ בְּיָמַי.[2]

Omri was the king of Israel, and he oppressed Moab for many days, for Kemosh was angry with his land. And his son succeeded him, and he said – he too – “I will oppress Moab!” In my days did he say [so] but I looked down on him and on his house, and Israel has gone to ruin, yes, it has gone to ruin forever! And Omri had taken possession of the land of Medeba, and he settled it [during] his days and half the days of his son, forty years, but Kemosh [resto]red it in my days.[3]

The events described here are unlikely to have taken place early in Omri’s reign, while he was consolidating his rule and building his new capital city in Samaria. It is even possible that “Omri” in the Mesha inscription stands for the Omride dynasty and not the person Omri,[4] and that the conqueror was his son Ahab.

If so, the “son” against whom Mesha goes to war and pushes out of the area may be Ahab’s son, Joram. This would allow the inscription to comport with the broad outline of the biblical account of Mesha’s rebellion in Kings:

מלכים ב ג:ד וּמֵישַׁע מֶלֶךְ מוֹאָב הָיָה נֹקֵד וְהֵשִׁיב לְמֶלֶךְ יִשְׂרָאֵל מֵאָה אֶלֶף כָּרִים וּמֵאָה אֶלֶף אֵילִים צָמֶר. ג:ה וַיְהִי כְּמוֹת אַחְאָב וַיִּפְשַׁע מֶלֶךְ מוֹאָב בְּמֶלֶךְ יִשְׂרָאֵל. ג:ו וַיֵּצֵא הַמֶּלֶךְ יְהוֹרָם בַּיּוֹם הַהוּא מִשֹּׁמְרוֹן וַיִּפְקֹד אֶת כָּל יִשְׂרָאֵל.

2 Kings 3:4 Now King Mesha of Moab was a sheep breeder; and he used to pay as tribute to the king of Israel a hundred thousand lambs and the wool of a hundred thousand rams.3:5 But when Ahab died, the king of Moab rebelled against the king of Israel. 3:6 So King Jehoram promptly set out from Samaria and mustered all Israel.

The story ends with the following:

מלכים ב ג:כז …וַיְהִי קֶצֶף גָּדוֹל עַל יִשְׂרָאֵל וַיִּסְעוּ מֵעָלָיו וַיָּשֻׁבוּ לָאָרֶץ.

2 Kings 3:27 A great wrath came upon Israel, so they withdrew from him (=Mesha) and went back to [their own] land.

In short, this story from the beginning of 2 Kings explains how Israel’s army was chased out of Moabite territory, which in broad strokes is what the Mesha inscription claims.

Mesha Takes Israel’s Border Forts in the Transjordan

Mesha describes a number of specific sites which he takes from Israel in the Transjordan,including the area of Atarot, identified as Khirbet Ataruz (lns 10-11):

וְאִשׁ גָד יָשַׁב בְּאֶרֶץ עֲטָרֹת מֵעֹלָם. וַיִבֶן לֹה מֶלֶך יִשְׂרָאֵל אֶת עֲטָרֹת. וַאֶלְתָחֵם בַּקִר וַאֹחֲזֶהָ…

And the men of Gad lived in the land of Atarot from ancient times, and the king of Israel built Atarot for himself and I fought against the city and I captured it…[5]

Similarly, the inscription speaks about the dispute over Yahatz (Jahaz), identified as Khirbet el-Mudayna eth-Themed[6] (lns 18-21):

וּמֶלֶךְ יִשְׂרָאֵל בָּנָה אֶת יַהַץ וַיֵשֶׁב בָּה בְּהִלְתָחֲמֹה בִּי וַיְגַרְשֵׁהֻ כְּמֹשׁ מִפָּנַי וָאֶקַח מִמֹאָב מָאתֵן אִשׁ כָּל רָשֵׁהֻ וָאֶשָׂאֵהֻ בְּיַהַץ וַאֹחֲזֶהָ לָסֶפֶת עַל דִיבֹן.

And the king of Israel had built Yahatz and he stayed there during his campaigns against me, and Kemosh drove him away before my face. And I took two hundred men of Moab all its division(?) and I led it up to Yahatz and I have taken it in order to add it to Dibon.

The king of Israel built up Atarot (on Wadi el-Wala) and Yahatz (on Wadi eth-Themed) to serve as forts along the southern border of the territory that Israel had conquered.[7] These forts are situated to the northwest and northeast respectively of “the land of Dibon,” the term Mesha seems to use for the land between the Wadi el-Wala and Wadi eth-Themed in the north and the Arnon Stream (Wadi Mujib) in the south.[8]

Archaeological study of Iron II Atarot and Yahatz reveal that they were built using construction methods typical of Omride-dynasty sites west of the Jordan:

Elevated podium – Sites would be leveled and filled to create a flat surface upon which the structures were to be built.

Casemate wall – Two parallel walls going around the perimeter of the city with empty space between. These walls were periodically cut by short transverse walls running between the two, creating rectangular “casemate” spaces.

Six-chambered gate – The six-chambered or four-entry gate, made what would otherwise be the most vulnerable part of a city more secure, as it allowed for multiple defensive positions.

Elaborate glacis – Cities were built with sloping ramparts (glacis) designed to make it difficult for enemies to climb the wall or attack it with battering rams.

Moat – Moats dug around the perimeter of a city added a further layer of security.[9]

As Atarot and Yahatz have all these standard Omride features, this confirms Mesha’s claim that the sites were built by the Omrides.

Mesha Goes North: The Conquest of Nebo

In addition to his taking the southern forts of Yahatz and Atarot, Mesha describes how he conquered as far north as Nebo (lns 14-18):

וַיֹאמֶר לִי כְּמֹשׁ: לֵךְ אֱחֹז אֶת נְבֹה עַל יִשְׂרָאֵל. וַאֶהֱלֹך בַּלֵּלָה וַאֶלְתָחֵם בָּה מִבְּקֹעַ הַשַׁחֲרִת עַד הַצָהֳרָם וַאֹחֲזֶהָ, וַאֶהֱרֹג כֻּלָה, שִׁבְעַת אֲלָפִן גְבָרִן וְגֻרִן וּגְבָרֹת וְגֻרֹת וּרְחָמֹת כִּי לְעַשְׁתָר כְּמֹשׁ הֶחֱרַמְתִהָ. וַאֶקַח מִשָׁם אֶ[ת כְּ]לֵי י־הוה וַאֶסְחַבְהֵם לִפְנֵי כְּמֹשׁ.

And Kemosh said to me: “Go take Nebo from Israel!” And I went in the night and I fought against it from the break of dawn until noon, and I took it and I killed [its] whole population, seven thousand men and boys (or “male citizens and aliens”) and women and girls (or “female citizens and aliens”) and servant girls, for I had put it to the ban for Ashtar Kemosh. And from there I took the [ves]sels of YHWH and I hauled them before the face of Kemosh.[10]

During the reigns of Ahab and Joram, Israel was at war with the nearby Aramean polity of Damascus. Mesha took advantage of the weakening of Israel under the pressure of Damascus in order to throw the yoke of the Northern Kingdom. According to the inscription, he extended his rule from the Dibon area north, taking control of the entire mishor. But this is not all he did; apparently Mesha expanded in the opposite direction as well.

Mesha Goes South: The Conquest of Horonaim

After describing Mesha’s northern conquests, the Inscription turns to what appears to be his take-over of an area in the south (lns. 31-33):

וְחוֹרֹנֵן יָשַׁב בָּה ב[… …וַיֹ]אמֶר לִי כְּמֹשׁ: רֵד הִלְתָחֵם בְחוֹרֹנֵן. וַאֵרֵד [וַאֶלְתָחֵם בַּקִר וַאֹחֲזֶהָ וַיְשִׁבֶ]הָ כְּמֹשׁ בְּיָמַי.

And [at] Horonaim there lived [… …][11] And Kemosh said to me: “Go down, fight against Horonaim!” I went down [and I fought against the city and I captured it] and Kemosh [res]tored in my days.

That Horonaim is south of the Arnon is clear from references to the city in the Bible (Isaiah 15: 5; Jeremiah 48:34).

This expansion of Mesha to the north and the south created the first territorially developed kingdom in Moab, located both north and south of the Arnon Stream. His conquests decided the location of the border between Moab and Israel in the later phases of the Iron Age – near the northern edge of the Dead Sea.

The combined evidence of the biblical account and the Mesha Inscription suggests that Israel under the Omrides conquered the Transjordan all the way down to Wadi el-Wala and Wadi eth-Themed and built forts there. This situation persisted until the time of Joram, when Israel was weakened by its wars with Damascus. Mesha, king of Moab, saw this as an opportunity, and pushed Israel far to the north. At the same time, he also expanded Moab to the south. This created Moab as a strong polity that lasted for centuries afterward.

The Mishor before Omri and Mesha?

Who ruled the mishor before Omri’s conquest?[12] Can we say anything about the history of this region before the Israel-Moab conflict? We believe that at least partial answers to these questions can be found through a critical reading of the story about the war of Israel against Sihon king of Heshbon in Numbers 21:21-35.

Moab South of the Arnon Stream

As the Israelites approach the Transjordan north of the Arnon Stream, which Numbers 21 calls the kingdom of Sihon the Amorite, it describes the border between this Amorite polity and that of Moab:

במדבר כא:יג …וַיַּחֲנוּ מֵעֵבֶר אַרְנוֹן אֲשֶׁר בַּמִּדְבָּר הַיֹּצֵא מִגְּבוּל הָאֱמֹרִי כִּי אַרְנוֹן גְּבוּל מוֹאָב בֵּין מוֹאָב וּבֵין הָאֱמֹרִי.

Num 21:13 and they encamped beyond the Arnon, that is, in the wilderness that extends from the territory of the Amorites. For the Arnon is the boundary of Moab, between Moab and the Amorites.

According to this, Moab was restricted to the area south of the Arnon Stream, with a different polity ruling the mishor area to its north.[13]

Later in the chapter comes the Heshbon Ballad, which ostensibly describes how Sihon defeated the Moabites in battle:

במדבר כא:כח כִּי אֵשׁ יָצְאָה מֵחֶשְׁבּוֹן

לֶהָבָה מִקִּרְיַת סִיחֹן

אָכְלָה עָר מוֹאָב

בַּעֲלֵי בָּמוֹת אַרְנֹן.

Num 21:28 For fire went forth from Heshbon,

Flame from the city of Sihon,

Consuming Ar of Moab,

Ba’alei Bamot by the Arnon.[14]

Archaeology may clarify the polity to which this poem refers. A system of well-preserved, fortified sites south of the Arnon Stream date according to their pottery and radiocarbon determinations to the late 11th and 10th century B.C.E., and these were abandoned before 900 B.C.E.

These forts probably protected the borders of an early Moabite polity south of the Arnon Stream. The hub of this territorial entity appears to have been located at Khirbet Balua, which has been identified as biblical Ar of Moab. The site is famous for the Balua Stele, depicting the local ruler standing between two deities in Egyptian style, and which one of the authors (I.F.) has argued dates to this period as well.[15]

This early polity likely arose in the arid part of Moab at this time for two reasons: First, pollen residues in a core of sediments from the Dead Sea reveals this there was a short period of improved climatic conditions in the beginning of the Iron Age. Second, copper production in Wadi Faynan south of the Dead Sea made the region prosperous.

An Amorite Polity in the Mishor?

The biblical text describes Israel’s conquest of Sihon the Amorite:

במדבר כא:כג…וַיֶּאֱסֹף סִיחֹן אֶת כָּל עַמּוֹ וַיֵּצֵא לִקְרַאת יִשְׂרָאֵל הַמִּדְבָּרָה וַיָּבֹא יָהְצָה וַיִּלָּחֶם בְּיִשְׂרָאֵל. כא:כד וַיַּכֵּהוּ יִשְׂרָאֵל לְפִי חָרֶב וַיִּירַשׁ אֶת אַרְצוֹ מֵאַרְנֹן עַד יַבֹּק …כא:כה וַיִּקַּח יִשְׂרָאֵל אֵת כָּל הֶעָרִים הָאֵלֶּה וַיֵּשֶׁב יִשְׂרָאֵל בְּכָל עָרֵי הָאֱמֹרִי בְּחֶשְׁבּוֹן וּבְכָל בְּנֹתֶיהָ.

Num 21:23 … Sihon gathered all his people and went out against Israel in the wilderness. He came to Yahatz and engaged Israel in battle. 21:24 But Israel put them to the sword, and took possession of their land, from the Arnon to the Jabbok… 21:25 Israel took all those towns. And Israel settled in all the towns of the Amorites, in Heshbon and all its dependencies.

Though in late-monarchic times Heshbon was part of Moab (Isaiah 15:4, 16:8-9; Jeremiah 48:2, 34), in the biblical tradition, the pre-Israelite rulers of this area were the Amorites, not the Moabites. The depiction of a non-Moabite polity in the mishor ruling from the city of Heshbon may preserve a genuine memory of the pre-Omride situation in this territory: Until the expansion of Mesha, the mishor was not considered part of Moab; rather, it was ruled by a late-Amorite/Canaanite city-state.[16]

Verse 26, which immediately precedes the Song of Heshbon, is peculiar; it reads:

במדבר כא:כו כִּי חֶשְׁבּוֹן עִיר סִיחֹן מֶלֶךְ הָאֱמֹרִי הִוא וְהוּא נִלְחַם בְּמֶלֶךְ מוֹאָב הָרִאשׁוֹן וַיִּקַּח אֶת כָּל אַרְצוֹ מִיָּדוֹ עַד אַרְנֹן.

Num 21:26 For Heshbon was the city of Sihon the king of the Amorites, who had fought against the former (or “first”) king of Moab and taken all his land up to the Arnon.[17]

Although the Bible claims that the king of Heshbon took the mishor from Moab, this may reflect polemical arguments between Israel and Moab about territory, dating from the Omride period or even from the first half of the 8th century (the Nimshide period).

Clearly, the biblical text wishes to claim that before the Israelites ever arrived, the Moabites were limited to the territory below the Arnon Stream, and that Israel took the entireTransjordan north of the Arnon Stream from a third polity. In contrast, the Mesha inscription claims that Moab ruled the land of Dibon, up to the border at Wadi al-Wala and Wadi eth-Themed.

Apparently, with the fall of this Amorite/Canaanite polity in the Transjordan to Omride Israel, the land was split with Israel taking the mishor and Moab taking the land of Dibon. In their respective texts, each side lays claim to the mishor; the Bible presents Israel as having the right to rule down to the Arnon Stream and the Mesha inscription describes Moab’s setting their eyes on the north. Eventually, the polemic became a battle, and Mesha’s Moab ended up ruling the mishor, as far north as Nebo.

The Bible describes a battle at Yahatz between Israel and Sihon, while the Mesha inscription describes how Omri built up the area of Yahatz. Despite the Bible’s placing Israel’s conquest of the mishor in the wilderness period under Moses, we believe that this conquest occurred in the 9th century under the Omrides. Thus, both Numbers 21 and the Mesha Inscription are referencing the same historical events, namely, the Omrides’ north-south campaign to conquer the mishor in the early 9th century B.C.E.[18]

Ancient Information in a Late Book

The book of Numbers may well be the latest scroll of the Pentateuch,[19] yet it preserves shreds of Israelite traditions regarding the conquest of the mishor from a late Canaanite king who ruled from Heshbon, as well as memories about the existence of an early Moabite kingdom further south. These traditions must have first been transmitted in the Northern Kingdom orally; perhaps they originated from the Temple of YHWH at Nebo referred to in the Mesha Inscription. They were probably committed to writing in the first half of the 8th century, when complex writing appears for the first time in Israel.[20]

The compilation of these traditions may have been carried out during the reign of Jeroboam II (early to mid-8th century B.C.E.), the greatest king of Israel, possibly in conjunction with an Israelite claim to this territory. His reign was characterized by an administrative reorganization of Israel and perhaps the compilation of foundation myths, royal traditions and heroic tales of the kingdom. The story of the war against Sihon and the Song of Heshbon found their way to Jerusalem after the fall of the Northern Kingdom in 722 B.C.E., and were integrated into the book of Numbers by a still later redactor, probably during the Persian period.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

June 18, 2018

|

Last Updated

November 23, 2025

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Prof. Israel Finkelstein is the Jacob M. Alkow Professor of the Archaeology of Israel in the Bronze and Iron Ages at Tel Aviv University, whence he received his M.A. and Ph.D. in archaeology. He and is the director of the Megiddo expedition, is well known for his revised lower chronology, for which he won the Dan David Prize. Among his many publications are The Forgotten Kingdom, The Archaeology of the Israelite Settlement, and his best selling The Bible Unearthed (with Neil Asher Silberman).

Prof. Thomas Römer is a professor of Hebrew Bible at the Collège de France and occupies its chair in Milieux Bibliques. He holds a Th.D. in biblical studies from the University of Geneva and an L.Th from the University of Heidelberg. Römer was awarded a cursus honora doctorate from the University of Tel Aviv, and among his many publications are Israel’s Väter (German), The So-Called Deuteronomistic History, and Dark God: Cruelty, Sex, and Violence in the Old Testament.

Essays on Related Topics: