Edit article

Edit articleSeries

Journeys

Seek Meaning, and You Shall Find

Categories:

My path to biblical studies, like that of many others, branched out from my road to the rabbinate. Raised in a non-traditional home, Judaism took hold of me in the local synagogue, where my musical ear absorbed the Hebrew liturgy. A non-conformist by nature, I became virtually the only observant Jew in my public school.

My path to biblical studies, like that of many others, branched out from my road to the rabbinate. Raised in a non-traditional home, Judaism took hold of me in the local synagogue, where my musical ear absorbed the Hebrew liturgy. A non-conformist by nature, I became virtually the only observant Jew in my public school.

Planning to become a rabbi, I enrolled in the double-degree undergraduate program of the Jewish Theological Seminary and Columbia University. At JTS I learned that Bible belonged to Jewish studies, and at Columbia I learned that all disciplines are somehow related. These two lessons were never lost on me.

Introduced to the critical study of the Bible and its ancient Near Eastern background in the first year, I got hooked. I knew I had a knack for biblical philology when I knocked our instructor, Shalom Paul, off his chair in a course in Second Isaiah.

We came to verse 41:3, which describes the divinely backed onslaught of a champion from the East (Cyrus). The second clause, אֹרַח בְּרַגְלָיו לֹא יָבוֹא, has stymied interpreters who have assumed that the term ʾoraḥ must have its usual meaning of “path,” leading to such translations as “by a path his feet have not traveled before” (the New International Version)—a poor fit with the passage’s sense and the Hebrew grammar.

Exercising my budding Sprachgefühl (feel for language), I suggested that ʾoraḥ must denote some kind of obstruction and that the clause must mean something like, “No obstacle will go into/onto his feet.” I had no idea that the term ארח occurs in the sense of “shackles” in the Aramaic Proverbs of Ahiqar and that H. L. Ginsberg, Paul’s teacher before he was mine, had interpreted the line from Isaiah in its light.

In all my philological work I have given pride of place to a principle that was inculcated by Ginsberg and my teacher Moshe Held, and one that was anticipated by Saʿadia Gaon, Ibn Janaḥ, and Abraham Ibn Ezra: posit that a source originally made sense and then seek that sense.

During my graduate school years, a new inscription from Sarepta was found and published. Although it was written in Ugaritic characters, the phraseology struck me as Phoenician. Once the text was properly cleaned, it turned out I was right. David Marcus and I thought an unknown word in the Akkadian inscription of Idrimi of Alalakh should mean “corpse.” Forty years later I found the word in Aramaic. Those same principles have informed my decades-long work on cracking the dense language of Job and my recent translation of it.[1]

My work as a biblicist involves both ancient Near Eastern and Jewish studies, and, though not (in the end) a rabbi, I have always written (divrei Torah, articles, reviews, a chunk of The Timetables of Jewish History) for and given time to the Jewish public. My Torah study partners in New York and I launched and edited a Devar Torah column, syndicated in several Jewish newspapers. In New York and Jerusalem I initiated and led Shabbat prayer programs for very young children. After all, that is how I got started.

For me such efforts are more cultural than spiritual, although they are also spiritual. Spirituality is like musicality: everyone has some potential, and those who have more than a little can cultivate it. No ear, no music; no sense of an otherly reality, no spirituality.

My engagement in biblical studies as an academic discipline, though triggered by Jewish interests, has been a continuously stimulating intellectual adventure. The Bible is literature, not a discipline. But I can’t think of any discipline one cannot draw upon to enhance biblical interpretation.

My route has tended toward the philological-linguistic and the literary, with psycholinguistics and discourse analysis bridging the two. It was in a graduate course in psycholinguistics, with its generative orientation, that I was introduced to the work of Stanley Fish, and I continued to trail him as he moved from reader response to deconstruction to pragmatism—the notion that in order to obtain the results that you seek, you find and apply the method that works best. I came to believe that meaning is not inherent but is made, by the observer of the world, by the reader of a text. Texts don’t come alive (in fact, they are silent) until they are brought to life in an act of reading.

By the same logic, texts are not inherently sacred but are made sacred by people, usually by communities of people. The divine, the principle of existence however one understands and personifies it, does not emerge from texts but is found in texts by readers who are searching for it (through what we call midrash). I suppose that when I seek the divine, I could be looking in any number of places. But being who I am, and belonging to the communities to which I belong, I seek meaning and meaningfulness in the Torah and in the overwhelming wealth of interpretative literature that has been transmitted around it.

The leading light of my spiritual community, the scholar-rabbi-theologian Art Green, once called my attention to a most insightful line from the 18th century neo-Kabbalistic tract of Rabbi Pinchas of Koretz, Midrash Pinchas: כי התפלה הוא עצמות האלקות ממש “Prayer is the very essence of Godhood.” One experiences the divine through the act of prayer, and, one may add, through sacred ritual acts, through Godly work, and, yes, through looking for it in one’s sacred texts. Seek meaning and connection, and ye shall find them.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

December 21, 2021

|

Last Updated

February 27, 2025

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

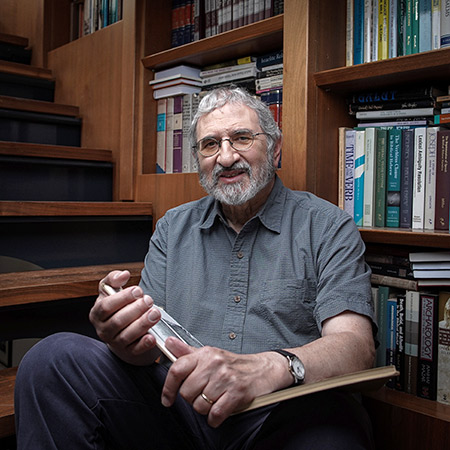

Prof. Edward L. Greenstein is Professor Emeritus of Bible at Bar-Ilan University. He received the EMET Prize (“Israel’s Nobel”) in Humanities-Biblical Studies for 2020, and his book, Job: A New Translation (Yale University Press, 2019), won the acclaim of the American Library Association, the Association for Jewish Studies, and many others. He has been writing a commentary on Lamentations for the Jewish Publication Society.

Essays on Related Topics: