Edit article

Edit articleSeries

Targum Onkelos and the Translation of Place Names

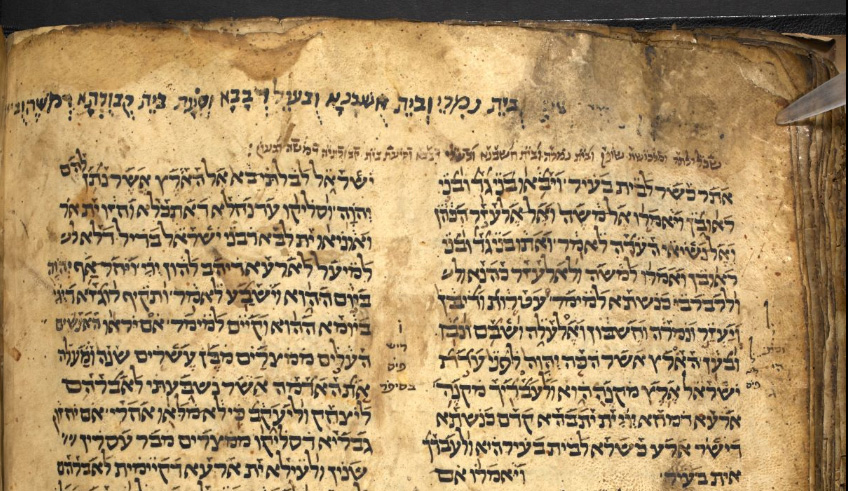

Pentateuch with Onkelos on the side (MS Harley 5709, 191r). The Hebrew toponyms are untranslated, and the space is left blank, except for the Hebrew word Ataroth. British Library

Targum Onkelos is the best-known of the Aramaic translations (targumim—singular, targum) of the Torah that were composed in both Babylon and Israel to be read at the synagogue and studied.[1] Onkelos is described in the Babylonian Talmud as a proselyte, who became a student of Rabbi Eliezer and Rabbi Joshua (b. Megillah 3b). In the equivalent source in the Jerusalem Talmud (j. Megillah 1.9; 71c) the name is Aquilas, and he is described as the author of the Greek translation of the Bible known by that name.[2]

Targum Onkelos appears to have developed in two phases: It was originally composed in Judea, as evidenced by Greek words it contains, which are generally found in works from Israel (not from Babylonia). This original work was likely composed between 50–150 C.E., as implied by the links between the Targum and the Dead Sea Scrolls. Later, this Aramaic translation was adopted in Babylonia and revised.[3]

It became so popular in Babylonian rabbinic circles that the Babylonian Talmud requires Jews to read it every week together with the weekly portion, in the law known as שניים מקרא ואחד תרגום, “[read] scripture twice and the translation once” (b. Ber. 8a).[4] It is included in most standard Rabbinic Bibles near the Hebrew, and vocalized for ease of reading. Some Yemenite synagogues still read Onkelos out loud as part of the Torah reading ceremony.

Translating Place Names

For the most part, Targum Onkelos is a literal, word-for-word translation, though with a substantial amount of deviations.[5] One area of such deviation is the translation of place names.[6] Most commonly, Onkelos simply uses the Hebrew name without translating it into Aramaic. Nevertheless, in some cases, Onkelos translates place names into Aramaic. These exceptions fall into several categories.

1. Aramaic Equivalents for Easier Identification

Onkelos sometimes translates a name to help the reader identify the place. This was first suggested by R. Nathan Adler (1803–1890), the Chief Rabbi of England, in his commentary on Onkelos:[7]

שמות האומות והמקומות הימים והנהרות שנשתנו מזמן נתינת התורה עד ימי אונקלוס, תרגם כאשר נקראו בשמותיהן בימיו.

The names of the nations, places, seas, and rivers that were changed from the time of the giving of the Torah until the days of Onkelos, he translated them with their contemporary counterparts.

The following examples exemplify Adler’s claim:

|

|

Torah |

Onkelos |

|

Gen 2:14 |

חִדֶּקֶל, Ḥideqel (=Tigris) |

דִגְלָת, Diglat |

|

Gen 8:4 |

הָרֵי אֲרָרָט, Ararat Mountains |

טוּרֵי קַרְדּוֹ, Kardo Mountains[8] |

|

Num 13:22 |

צֹעַן, Tzoʿan |

טַאנֵיס, Tanis[9] |

|

Num 21:33 |

הַבָּשָׁן, the Bashan |

מַתְנַן, Matnan |

|

Num 34:11 |

יָם כִּנֶּרֶת, Kinneret (=Galilee) Sea |

יָם גִּנֵיסַר, Gennesaret Sea |

|

Deut 2:23 |

כַּפְתּוֹר, Kaphtor (Crete) |

קְפוּטקְיָא, Cappodocia (=central Turkey)[10] |

|

Deut 3:4 |

חֶבֶל אַרְגֹּב, Argob district |

בֵּית פֶּלֶךְ טְרָכוֹנָא, Terakhona district[11] |

By using Aramaic names instead of Hebrew ones, Onkelos was trying to make it easier for Aramaic speakers to identify these biblical sites.[12] Some of these names are familiar, while others are unique to Onkelos, and scholars debate whether they were once well known to Aramaic speakers and when.[13]

2. Connecting the Name to Narrative Context

In several places where the Bible itself gives an explanation to the place name,[14] Onkelos translates the place name into Aramaic:

מַסָּה וּמְרִיבָה, Massah u-Meribah (Exod 17:7)—the name means “trial and quarrel.” Onkelos renders it נִסֵיתָא וּמַצוּתָא, translating the terms into Aramaic rather than transliterating them.[15] By using the Aramaic terms, Onkelos creates a link between the place and its explanation in Aramaic: עַל דִּנצוֹ בְּנֵי יִשׂרָאֵל וְעַל דְּנַסִיאוּ קֳדָם יְיָ .

תַּבְעֵרָה, Tabʿerah (Num. 11:3)—The name, from the root ב.ע.ר, means “burning.” Onkelos translates this as דְּלֵיקְתָא, Deleyqta, from the Aramaic root ד.ל.ק, “to burn.” This rendering clarifies the link between the place name and the event that caused the place to be named: אֲרֵי דְלֵיקַת בְּהוֹן אִישָׁתָא מִן קֳדָם יְיָ—“because the fire from before the Lord burned among them.”[16]

קִבְרוֹת הַתַּאֲוָה, Qivrot HaTaʾavah (Num. 11:34)—The name, connected to Israel’s overconsumption of quail, means “the graves of desire.” Onkelos renders it קִבְרֵי דִמְשַׁאֲלֵי, Qivrei de-Mishʾalai, meaning “graves of those who demanded.” This too connects to the story’s context, as the Targum goes on to explain אֲרֵי תַמָּן קְבַרוּ יָת עַמָּא דְּשַׁאִילוּ “for there they buried the people who made the demand.”[17] Benzion Berkowitz (1803–1879) notes in his שמלת גר “Clothing of the Proselyte”[18] commentary on Onkelos, that the specific translation here is also unusual:

התאוו תאוה—"שאילו." בכל לשון תאוה תרגם בלשון "רעות" רק בזה לפי שאין על תאות הלב חטא מות כי אם על שאלתם למלאות תאותם.

“Had a desire”—[Onkelos translates] “demanded.” Everywhere else, he translated the term taʿavah as “desire” (=Aramic root ר.ע.ו), and only in this case, since a person’s sinful heart’s desire should not end in a punishment of death, [did he translate “demand], since [they were punished] only for demanding that their desire be fulfilled.

In these places, Onkelos renders the Hebrew place names into Aramaic so that the puns or plays on words in the original Hebrew are visible in Aramaic as well.

3. Midrashic Translation of Place Names

While the two types of Aramaic rendering described above fit with the style of the Onkelos translation to prioritize the literal or simple meaning of the text, in some cases Onkelos offers homiletical interpretations of a toponym, appearing in the rabbinic sources.[19]

אֶרֶץ הַמֹּרִיָּה “Land of Moriah” (Gen 22:2)—Onkelos reads the same as the rabbis (b. Berakhot 62b; Genesis Rabbah 55:7; 56;10) when he translates this as לַאֲרַע פֻּלחָנָא, “land of worship,”[20] referring to the Temple Mount in Jerusalem. This emphasizes that the choice of the site where the Temple was to be built was assigned to Abraham, hundreds of years before King Solomon has built it.[21]

וּמִמִּדְבָּר מַתָּנָה “from the wilderness to Matanah” (Num 21:18)—Onkelos translates this as וּמִמַדבְּרָא אִתיְהֵיבַת לְהוֹן, “and from the wilderness it was given to you.” The second toponym here is being translated not as a place but as “gift.” The Hungarian scholar of midrash, Yehudah (Otto) Komlosh (1913–1988) of Bar Ilan University, suggests that Onkelos is alluding to Miriam’s well, which, according to the rabbis, miraculously accompanies Israel in the wilderness (b. Taʿanit 9a; Tanhuma Chukkat 21).[22]

In my opinion, however, the subject of the verb אתיהיבת is the Torah, and Onkelos is following other midrashim, such as [23]אם אדם משים עצמו כמדבר זה שהכל דשין בו תורה ניתנה לו במתנה, “if a person makes himself [humble] like a wilderness on which everyone tramples, Torah is given to him like a gift (matanah)” (b. Eruvin 54a).

בֵּין פָּארָן וּבֵין תֹּפֶל וְלָבָן “between Paran and Tophel, and Laban” (Deut 1:1)—Onkelos translates this as בְּפָארָן אִתַּפַּלוּ עַל מַנָּא, “in Paran they made light of the manna.” This is a reference to the biblical stories in which the Israelites complain about the manna (11:4–6, 21:5). He reads the word Tophel as a verb, and Laban, meaning “white” as a reference to the white manna (Exod 16:31).

וְדִי זָהָב “Di-zahab” (Deut 1:1)—Onkelos translates this toponym as וְעַל דַּעֲבַדוּ עֵיגַל דִּדהַב, “and that they worshiped the golden calf,”[24] a reference to the story in in Exodus 32. Both this example and the previous one fit with the idea found in rabbinic midrash that the opening speech of Moses in Deuteronomy was aimed at rebuking the Israelites. As such, the place names in the opening verse are taken as subtle reminders of what sins they committed in the wilderness (Sifrei Deuteronomy, 1:1).

If Onkelos is taking these midrashim from rabbinic sources, then this represents an early effort to incorporate rabbinic midrashim into popular knowledge. Alternatively, the borrowing could be in the other direction, or both could be taking it from interpretations well-known in rabbinic circles.

Whatever the case, all these examples are motived by educational and theological purposes. In Numbers 32, however, Onkelos seemingly veers away from transcribing the Hebrew, translating terms into Aramaic in different ways, without any compelling reason.

Onkelos and the Jerusalem Targum

When the tribes of Gad and Reuben ask Moses to live in the Transjordan, they say:

במדבר לב:ג עֲטָרוֹת וְדִיבֹן וְיַעְזֵר וְנִמְרָה וְחֶשְׁבּוֹן וְאֶלְעָלֵה וּשְׂבָם וּנְבוֹ וּבְעֹן. לב:ד הָאָרֶץ אֲשֶׁר הִכָּה יְ־הוָה לִפְנֵי עֲדַת יִשְׂרָאֵל אֶרֶץ מִקְנֶה הִוא וְלַעֲבָדֶיךָ מִקְנֶה.

Num 32:3 Ataroth, Dibon, Jazer, Nimrah, Heshbon, Elealeh, Sebam, Nebo, and Beon—32:4 the land that YHWH subdued before the congregation of Israel—is a land for cattle; and your servants have cattle.

The first verse is just a list of toponyms,[25] and as such we might expect Onkelos to simply copy them as is. And yet, in the standard printed editions of Onkelos, we find a nonliteral translation (it should have been translated עטרות ודיבון), and it is in disagreement with the rabbinic instruction:

|

Verse |

Onkelos |

Annotation |

|

עֲטָרוֹת (Atharot) |

מַכְלֶלְתָּא (Makhlelta)[26] |

Aramaic translation |

|

וְדִיבֹן (Dibon) |

וּמַלְבֶּשְׁתָּא (Malbeshta) |

Alternative Aramaic name |

|

וְיַעְזֵר (Jazer) |

וְכּוּמְרִין (Kumrin) |

Alternative Aramaic name |

|

וְנִמְרָה (Nimrah) |

וּבֵית נִמְרִין (Beth-Nimrin [House of Nimrin]) |

Aramaic rendering of Hebrew name |

|

וְחֶשְׁבּוֹן (Heshbon) |

וּבֵית חוּשְׁבָּנָא (Beth-Hushbana) |

Aramaic rendering of Hebrew name |

|

וְאֶלְעָלֵה (Elealeh) |

וּבַעֲלֵי דְבָבָא (enemies) |

Free rendering/ translation |

|

וּשְׂבָם (Sebam) |

וְסִימָא (Sima) |

Alternative Aramaic name |

|

וּנְבוֹ (Nebo) |

וּבֵית קְבוּרְתָּא דְמֹשֶׁה (burial spot of Moses) |

Free rendering/ translation |

|

וּבְעֹן (Beon) |

וּבְעוֹן (Beon) |

Hebrew name |

Only one of the nine toponyms directly represents the Hebrew; two others are a slight Aramaization of the Hebrew. In four, he uses Aramaic names in place of the Hebrew names, and in two, he renders them freely. There seems to be little reason for Onkelos to have done this here.

These translations are especially surprising in this context, given that the Babylonian Talmud says explicitly about Onkelos here (b. Berakhot 8a–b, Munich 95):

אמ[ר] רב הונא בר יהודה אמ[ר] רב מנחם א"ר אמי: "לעולם ישלים אדם פרשיותיו עם הצבור שנים מקרא ואחד תרגום ואפי[לו] עטרות ודיבון."

Rav Huna b. Yehudah said in the name of Rav Menachem who said in the name of R. Ammi: “Let one always review his [Torah] chapters along with the congregational readings, twice in the text itself and once in the Targum — even ‘Ataroth and Dibon…’ (Num 32:3)”

Why does R. Ammi’s make this point specifically concerning this verse? Rashi in his Talmud commentary (ad loc.) explains that the reason is שאין בו תרגום, “there is no translation,” namely that Targum Onkelos simply doesn't translate this list of names but skips over this list altogether. The Talmud’s point, according to Rashi, is that this verse still needs to be read a third time in the Hebrew, since there is no Aramaic. This implies that both the Talmud and Rashi did not have the Aramaic rendering of this verse quoted above.

Tosafot: Onkelos vs. Jerusalem Targum

The 12th century glosses on the Talmud, known as Tosafot, help clarify this situation.[27] The gloss begins by quoting Rashi’s interpretation, and continues:

וקשה אמאי נקט עטרות ודיבון שיש לו מ"מ תרגום ירושלמי. היה לו לומר ראובן ושמעון או פסוקא אחרינא שאין בו תרגום כלל.

There is a difficulty here. Why does [R. Ammi] choose [the verse] “Ataroth and Dibon,” which at least has the Jerusalem Targum. [If his point was what Rashi suggested], he should have chosen “Reuben and Simon…” (Exod 1:2–4).[28]

Tosafot refers here to the Jerusalem Targum, what scholars call Targum Pseudo-Jonathan,[29] one of multiple Jerusalem Targums written in Israel, and whose key feature is midrashic expansion. Tosafot notes that, unlike Onkelos, the Jerusalem Targum does translate the places in this verse into Aramaic. Thus, the gloss suggests a different interpretation of R. Ammi’s rule:

ויש לומר משום הכי נקט עטרות ודיבון אע"ג שאין בו תרגום ידוע אלא תרגום ירושלמי וצריך לקרות ג' פעמים העברי מ"מ יותר טוב לקרות פעם שלישית בתרגום.

It can be suggested that this is the reason [R. Ammi] chose the Atarot and Dibon passage, because even though the common Targum [=Onkelos] does not translate it, but only the Jerusalem Targum, and that [if we were to stick to only reading Onkelos] we should read the verse three times in Hebrew, nevertheless, it is better to read it the third time in the Targum [i.e., in the Jerusalem Targum’s Aramaic rending instead of Onkelos’s Hebrew].[30]

Tosafot’s comment helps us understand what happened with the text of Onkelos to Num 32:3. Since according to Tosafot, R. Ammi is requiring people to read the Jerusalem Targum version of Numbers 32:3 instead of Onkelos, the printer of the Mikraot Gedolot (Rabbinic Bible), starting in the Venice printing of 1525, simply replaced Onkelos with an Aramaic translation taken from one of the Jerusalem Targums.[31]

This point was already noted by Shadal (Samuel David Luzzato 1800–1865) in his book on Onkelos[32] and is supported by the best MSS of Onkelos, in which these words are left out entirely. Thus, in Alexander Sperber’s critical edition of Onkelos, he simply copies the Hebrew verbatim:

עֲטָרוֹת וְדִיבוֹן וְיַעְזֵר וְנִמְרָה וְחֶשְׁבּוֹן וְאֶלְעָלֵה וּשְׂבָם וּנְבוֹ וּבְעוֹן.

Ataroth, Dibon, Jazer, Nimrah, Heshbon, Elealeh, Sebam, Nebo, and Beon.[33]

Is Onkelos Consistent?

As the examples adduced above illustrate, Onkelos translated place names in an inconsistent manner. Sometimes the reason is clear, such as when he wishes to make wordplay accessible to readers, or when a biblical toponym had a well-known Aramaic name. Nevertheless, even here he isn’t fully consistent, and when it comes to the inclusion of a midrashic reading of a toponym, the reason for a given choice is even more difficult to pin down.

Whether this is simply the result of the random nature of human choice in translation, or whether there is something more intentional involved, is difficult to say. One possibility is that the reason for the inconsistency is connected to the long history of transmission of the Targum; in other words, later scribes may have added more midrash when the earlier translator preferred just copying the Hebrew. Another possibility may be that it depends on the traditions that he had, oral rabbinic traditions, geographical traditions, and so on.

Perhaps more research into the question, looking at all the examples together, will shed more light on the subject; so, to quote an Aramaic saying, ואידך – זיל גמור, “as for the rest, go and study!” (b. Shabb. 31a).

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

July 13, 2020

|

Last Updated

March 17, 2025

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Prof. Michael Avioz is Associate Professor of Bible at Bar-Ilan University. He holds a Ph.D. in Bible from Bar Ilan University. Avioz’s books include Nathan’s Oracle (2 Samuel 7) and Its Interpreters, I Sat Alone: Jeremiah among the Prophets, and Josephus’ Interpretation of the Books of Samuel. His forthcoming book is Legal Exegesis of Scripture in the Works of Josephus (Bloomsbury).

Essays on Related Topics: