Edit article

Edit articleSeries

The Embarrassing Case of the Blasphemer: Did God Really Want Him Dead?

Karachi/Pakistan – Teachers and students protest against United State of America (USA). Slogan: We strongly protest against disrespect of our beloved prophet today on 5th October 2012. Ilyas Dean – 1232rf

We have a challenge. We call it Miqra or Tanakh. Christians know it as the Old Testament, and for the purposes of academic study and inter-religious dialogue, it is increasingly referred to as the Hebrew Bible.

Although there is ample evidence that originally the biblical text was malleable and existed in multiple versions, at some point – most likely in the beginning of the Common Era – it became difficult and then entirely impossible to revise. Judaism, in particular, has very strict rules to that effect and highly efficient techniques of enforcing these rules. In other words, Tanakh does not change; but the conditions of human existence and human ideas about our existence change all the time.

As a result, eventually certain parts of the Bible fall out of sync with the zeitgeist. Indeed, some of them become downright embarrassing.

Should We Execute Blasphemers?

There is no shortage of embarrassing passages in Tanakh, including several weekly portions of the Torah. Emor is no exception: here is what we find towards the conclusion of the parashah (translation is the author’s):

A man whose mother was Israelite and whose father was Egyptian went out in the camp and got into a fight with an Israelite man. The son of the Israelite woman cursed and belittled the Name, so they brought him to Moses… They placed him under guard in order to receive oral clarification from YHWH.

YHWH spoke to Moses saying, “Bring the belittler out of the camp, let everyone who has heard place their hands on his head, and let the whole community stone him. And speak to the children of Israel as follows: ‘Everyone who belittles his God, let them bear their transgression. Those who curse the name of YHWH should certainly die; the entire community should certainly stone them, be they full citizens or resident aliens. Whoever curses the Name is to be put to death’” (Lev 24:10-16).[1]

The passage makes clear that blasphemy is a capital offense. How might we apply this now? Should the State of Israel execute not only Jews – including secular ones – but also Christians, Moslems, Druze, and the Baha’is if any were to speak irreverently about the God of Israel? Should we adopt the perspective of Islamic extremists who stage violent protests over Mohammed cartoons and force governments to ban the movie Noah? Should Bible-loving Jews and Christians support the efforts of some countries to push U.N. resolutions that would limit freedom of expression with regard to religion? And did the Putin regime in Russia err on the side of lenience when it sentenced members of the punk group Pussy Riot to jail for “offending the feelings of the believers” by a mock anti-government prayer in a Moscow church?

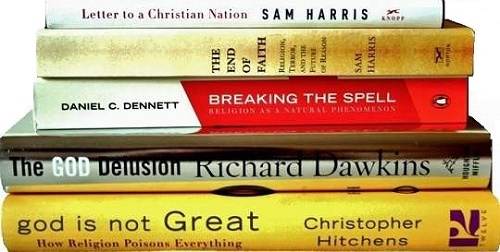

Some – most notably militant atheists – may cite this passage as yet another proof that the Bible is a relic of a barbaric period of human history and as such is obsolete. Others – most notably proponents of biblical literalism – may assert that no matter how offensive the content may seem it should be at the very least taken under advisement because to do otherwise, in the words of an Orthodox rabbi, would suggest that “God is not your Master. He is your slave.”[2] Yet others – most notably, liberal Jews and Christians – may prefer simply to ignore the piece, focusing instead on something much more congenial – such as the commandment, in Emor, to leave the edges of the field and the gleanings for the poor and the resident aliens (Lev 23:22).

Each of these responses is problematic. Discarding the Bible would deprive Judaism of its historical foundation. Insistence on following the scriptural precepts according to their literal meaning might turn Jews into an increasingly isolated sect, a curiosity at best and an object of hatred at worst. It is noteworthy that the Jewish community, by and large, has not taken the biblical text literally. And cherry-picking this text smacks of deception or, at least, distraction. In fact, this strategy is reminiscent of the preacher’s reaction to Homer Simpson’s bottom dragging across the windows of his new crystal cathedral, “Now, let us thank the Lord for this magnificent crystal cathedral, which allows us to look out upon His wondrous creation… Now quickly! Gaze down at God’s fabulous parquet floor. Eyes on the floor… still on the floor… always on God’s floor.”[3]

Can Modern Scholarship Help?

Fortunately, there is also a fourth path, one that has been blazed by the Talmudic sages and extensively treaded in Jewish tradition: when a scriptural text does not seem right, to check whether its plain meaning is the only possible one. As far as the blasphemy episode in Lev 24:10-16 is concerned, modern critical scholarship may be of substantial help in following this path.

When “modern critical scholarship” is mentioned with regard to Tanakh, most people tend to think about historical-critical methodologies, ones that presuppose a more or less extended history of tradition, compilation, composition, and editing behind the existing scriptural text (such methodologies are also called diachronic because they are interested in development over time). Indeed, from the nineteenth through the middle of the twentieth centuries, biblical scholarship was almost exclusively defined by such approaches, source criticism being the most prominent and well-known – some might say notorious – among them. By now, however, modern (and post-modern) exegetes have also developed a number of literary-critical (or synchronic) methodologies that address Tanakh as we know it, in its final, canonical form. One of these methodologies is narratology.

As suggested by the name, narratology seeks to understand how a text tells its story: how the plot unfolds, how the personages are characterized, what the narrator and the characters say and fail to say to and about each other and in what context, and how the narrated events present themselves from their point of view.

Does God Care about Blasphemy?

In approaching Lev 24:10-16, a narratologist would observe, first of all, that the blasphemy incident interrupts a long series of YHWH’s discourses that occupy not only the rest of the parashah but also almost the whole Book of Leviticus. These discourses contain instructions on various aspects of the cult, including multiple and highly detailed injunctions about precautions that the priests, the Levites, and the people should take in order to avoid desecrating the sanctuary or the community as a whole. There are, however, no injunctions in Leviticus against sacrilege by means of a speech act; the resultant impression is that the incident distracts YHWH from what really matters, namely, from preventing potentially profaning actions.

Indeed, it is not even clear whether the deity displays any prior concern about “belittling” of its name. The Third Commandment (“Do not bear the name of YHWH your God for nothing”; Exod 20:7) can be understood, in principle, as covering blasphemy, but the prohibition is too nebulous to be sure. The first half of Exod 22:27 is often translated along the lines of “Do not belittle God” but the parallel with the injunction against cursing a “prince” (nāśî’) in the second half of the verse suggests that Hebrew ’ĕlōhîm may refer here not to “God” or “gods” but to (human) “leaders” or “judges” – in accordance with the word’s traditional Jewish interpretation elsewhere in the legal sections of Exodus (21:6; 22:7-8).

What is more, when the alleged blasphemy is uttered, YHWH fails to strike the offender or even to demand his arrest and execution. Although in some parts of Tanakh – most notably in the Former Prophets – the deity is often quiescent, that is not usually the case in the Torah, certainly not in Exodus through Numbers. To cite just one example, YHWH immediately afflicts Miriam with a skin disease when she chides Moses for “taking an Ethiopian wife” (Num 12:1-10). By contrast, the deity does nothing when its own name is “belittled.” It is only when the people, at their own initiative, take the suspect into custody and make an oracular inquiry that YHWH pronounces the verdict. This suggests that if the Israelites did not impose upon YHWH the choice between pardoning the blasphemer and putting him to death the deity may have let the whole thing slip.

Did Moses Have a Choice?

Yet another indication of YHWH’s reluctance to meet verbal abuse with capital punishment is the unusual provision included in the divine verdict: stoning should be preceded by “those who hear” placing their hands upon the head of the alleged offender (Lev 24:14; contrast Num 15:32-36). Since the deity never clarifies what kind of utterance qualifies as blasphemy this, in essence, offers the people an opt-out (or a cop-out, if you wish): it is entirely up to them to decide whether what they are hearing actually constitutes “cursing” and “belittling.” In other words, YHWH hints that blasphemy is in the eye of the beholder.

This strategy, of course, allows for the opposite tendency as well, since the people remain free to define blasphemy broadly, treating every perceived affront to their cherished beliefs as a capital offense. That may be precisely the reason why YHWH finds it necessary to add a few words:

And everyone that smites the life-essence of a human should be surely put to death. And the one that smites the life-essence of a beast should pay for it; a life for a life. And those that cause injury to their fellows, whatever they have done should be done to them. A fracture for a fracture, an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth; whatever injury they cause to a human being the same should be caused to them. And the one that smites a beast should pay for it, and the one that smites a human should be put to death (Lev 24:17-21).[4]

It may appear that the deity suddenly changes the subject, but from the narratological standpoint, it is trying to tell the people something relevant to the issue of blasphemy – especially since the pronouncement hardly adds anything new to the commandments of Exodus 21-22 (see especially 21:14, 23-25). It is hardly accidental that all the cases reviewed here are based on the principle of talion, measure for measure: the deity reminds the listeners that what goes around comes around, be that murder, injury, or killing of another person’s beast. Applied to blasphemy, this principle means that if the Israelites insist on executing people for supposed slights to YHWH, it would be only fair that worshippers of other gods treat the Israelites the same way. And that would leave Israel exposed to violent reprisals simply for exalting Tanakh as a holy book because this book is chock-full of what other communities would be justified in interpreting as “cursing” and “belittling” of their gods.

To cite just a few examples, it sweepingly dismisses these gods as “non-deities” and “vanities” (Deut 32:21) as well as “nothingness” (1 Sam 12:21), refers to Baal of Ekron as Baal-Zebub – “Lord of the flies” (2 Kings 1), and mocks Dagon of Ashdod by gleefully telling a story of his mutilation (1 Sam 5:1-5). In short, YHWH implicitly warns the people that for those who live in a glass house it may not be a good idea to pelt alleged blasphemers with stones.

Have We Learned the Lesson?

Unfortunately, the warning goes unheeded:

Moses spoke to all the children of Israel, and they brought the belittler out of the camp, and pelted him with stones. Thus the children of Israel did what YHWH had commanded to Moses (Lev 24:23).[5]

The specific biblical episode ends here, together with the Emor portion, but reading the Torah to the end, a narratologist may discern a hint that at the end of his life Moses did in fact have second thoughts about blasphemy and especially about capital punishment for it. Deuteronomy, which is for the most part his last will and testament, never mentions blasphemy, except perhaps in the quotation of the Third Commandment (Deut 5:11). Strikingly, the only thing that the book describes as “belittling God” is the body of an executed person hanging from the tree (Deut 21:23).

There is, consequently, a good chance that today Moses would have acted differently – not for the sake of political correctness but rather because over the last two millennia it was primarily Jews who repeatedly found themselves on the receiving end of persecution for allegedly blaspheming first the Hellenistic and Greco-Roman gods, then Jesus, and then Mohammed. The descendants of Moses and his flock have learned from bitter experience about the terrible nature of religiously inspired violence. Narratology thus makes it possible to read Lev 24:10-23 not as a prescription for religious intolerance but rather as a powerful reminder that such intolerance is a two-way street.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

April 28, 2014

|

Last Updated

February 12, 2025

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Prof. Serge Frolov is Associate Professor of Religious Studies and Nate and Ann Levine Endowed Chair in Jewish Studies at Southern Methodist University. He holds a Ph.D. in religious studies from Clairmont Graduate University and another Ph.D. in modern history from Leningrad University. He is currently the editor of Hebrew Studies.

Essays on Related Topics: