Edit article

Edit articleSeries

The Etrog: Celebrating Sukkot With a Persian Apple

Etrog, 123rf, adapted.

The Torah mentions four plant species in connection with Sukkot:[1]

ויקרא כג:מ וּלְקַחְתֶּם לָכֶם בַּיּוֹם הָרִאשׁוֹן פְּרִי עֵץ הָדָר כַּפֹּת תְּמָרִים וַעֲנַף עֵץ עָבֹת וְעַרְבֵי נָחַל וּשְׂמַחְתֶּם לִפְנֵי יְ־הוָה אֱלֹהֵיכֶם שִׁבְעַת יָמִים.

Lev 23:40 On the first day you shall take the fruit of a splendid tree, branches of palm trees, boughs of leafy trees, and willows of the brook, and you shall rejoice before YHWH your God seven days.

What is the fruit of the splendid tree? The verse doesn’t specify. Jewish tradition has long interpreted the phrase as a reference to the etrog (citron), but how and when did this identification come about?

Ezra and Nehemiah: Olives?

The Persian period book of Nehemiah, the most ancient discussion of this practice, describes Ezra reading some version of this passage to the people on the second day of Tishrei. As the practice is unfamiliar to them, he clarifies:

נחמיה ח:טו ...צְאוּ הָהָר וְהָבִיאוּ עֲלֵי זַיִת וַעֲלֵי עֵץ שֶׁמֶן וַעֲלֵי הֲדַס וַעֲלֵי תְמָרִים וַעֲלֵי עֵץ עָבֹת לַעֲשֹׂת סֻכֹּת כַּכָּתוּב.

Neh 8:15 …Go out to the mountains and bring leafy branches of olive trees, pine trees, myrtles, palms and other leafy trees to make booths, as it is written.

“Leafy trees” and “palm branches” appear in both lists, but it is unclear how the rest match up. While it is possible that the book of Nehemiah had a different text of Leviticus than the one we now have,[2] if the text in Nehemiah is offering a reading of “fruit of a splendid tree,” it is apparently thinking of olives or olive branches.[3] Either way, Nehemiah does not include citrons.

In the Hasmonean period, the book of 2 Maccabees, composed in the late 2nd cent. / early 1st cent. B.C.E., describes a late celebration of Sukkot with a lulav, but seems unaware of the citron:

2 Macc 10:7 Therefore, carrying ivy-wreathed wands[4] and beautiful branches and also fronds of palm, they offered hymns of thanksgiving to him who had given success to the purifying of his own holy place.[5]

In fact, the text here skips over the “fruit of a splendid tree” entirely.

Josephus and Coins: Citrons

By the time of the Roman period, however, the citron is firmly ensconced in Jewish interpretation as the Sukkot fruit. Josephus (37 C.E.–ca. 100 C.E.), in his summary of the four species law, writes (Jud. Ant. 3:245):

They were to offer burnt-offerings and sacrifices of thanksgiving to God in those days, bearing in their hands a bouquet composed of myrtle and willow with a branch of palm along with fruit of the persea tree (i.e., the citron, which comes from Persia).[6]

This same interpretation is seen in an anecdote about the unpopular Hasmonean king and high priest, Alexander Jannai (Jud. Ant. 13.372):

As for Alexander, his own people revolted against him—for the nation was aroused against him—at the celebration of the festival (=Sukkot), and as he stood beside the altar and was about to sacrifice, they pelted him with citrons, it being a custom among the Jewish that at the festival of Tabernacles everyone holds wands made of palm branches and citrons—these we have described elsewhere.[7]

Notably, the citron appears alongside the palm branch (lulav) on a coin of the fourth year of the Great Revolt (69–70 C.E.), as well as on a coin from the time of Simon bar Kokhba’s revolt (132– 136 C.E.).

What happened in between the 2nd century B.C.E. and the 1st century C.E. that might explain why the citron was adopted as Sukkot’s official fruit?

A Brief History of Citrons

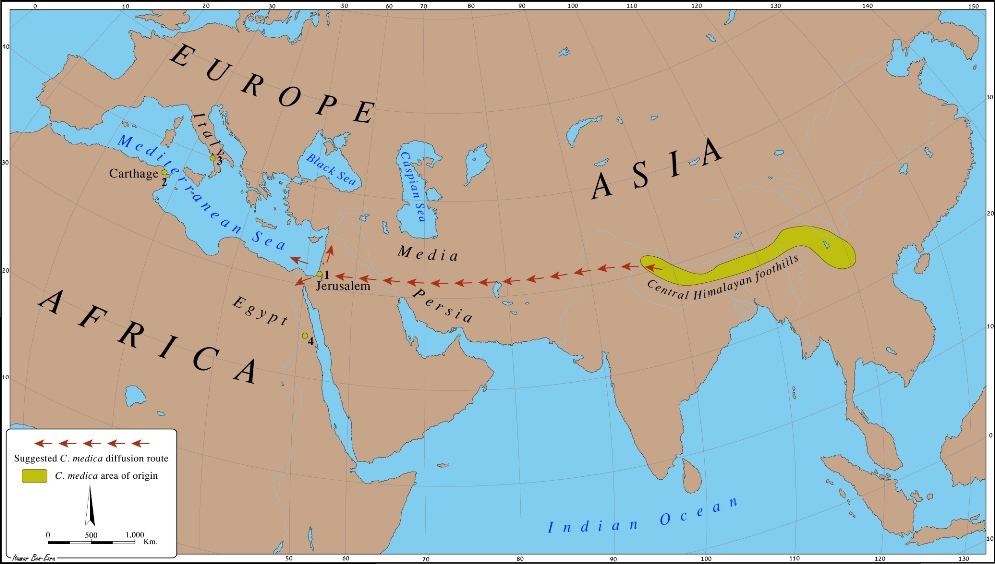

The citron (Citrus medica) is one of three naturally occurring citrus fruits, the other two being the pummelo (Citrus maxima) and the mandarin (Citrus reticulata).[8] All other citrus fruits are products of human cross-breeding, usually with the citron as the male genetic ancestor, having contributed the pollen.[9] The citron originated in eastern India and southern China and is the first citrus fruit to have made it to the west.

From Toronge to Etrog to Citron

In Hindi, the fruit is known as torange, from there we get the Persian toronge/turunj. As the “t” and “r” sounds were apparently pronounced with only a short vowel sound between, the Semitic languages added a prosthetic aleph[10] to assist pronunciation: hence the Aramaic אתרונגא etronga, Hebrew אתרוג etrog, and Arabic أترج utruj.[11] Farther west, the name was further changed through metathesis, with the final later ending up at the beginning of the word, hence Coptic (=Egyptian) ghitri, Greek κίτριον kitrion, Latin citrium, and eventually English citron.

A Luxury Import

Long before citron trees were cultivated in western Asia or Europe, the fruits themselves were known, likely as an exotic luxury product either imported by the palace or brought as expensive gifts for kings or gods.[12] For instance, citrons appeared already in ca. 2000 B.C.E., in the Sumerian city of Nippur, where archaeologists found remains of citrus seeds.[13]

Another such assemblage of seeds, though from a less secure archaeological context and less certainty that they were indeed citrus,[14] was found in a 12th century B.C.E context in Hala Sultan Tekke in Cyprus.[15] As citrons have an unusually long shelf-life for a fruit, they are an ideal choice for a long-distance import. Despite the sporadic appearance of the fruit as a luxury import or offering, it remained known only as an exotic fruit from the east for centuries.

The First Appearance of the Citron Tree in Israel

The earliest archaeological evidence for the cultivation of the tree outside Persia is in a garden in Ramat Rahel—nowadays part of west Jerusalem but in that period a Persian administrative center near Jerusalem—in a stratum dated to the 5th/4th century B.C.E. The excavators of the site have found the fossilized remains of citron pollen, on the western side of an extravagant Persian palace, trapped in one of the plaster layers of the pool.

While this pollen (rather than seeds) shows that wealthy Persian officials brought the tree with them to their gardens.[16] Considering this is the only place we find it, it confirms that the fruit remained a luxury item in this period.

Shortly after this we find other Mediterranean sites with evidence of citrons, first in Carthage (4th/3rd cent. B.C.E.),[17] the in the Vesuvius region (3rd cent. B.C.E. to 1st cent. C.E., depending on the site), and in several Roman settlements in Egyptian remote desert locations.[18] These show that the citron (and the lemon at this point) was beginning to appear and even grow in select locations in the Roman Empire.

Earliest References to the Etrog

The earliest literary reference to the citron is likely in a poem by Antiphanes (408–334 B.C.E.), where he refers to it as a golden apple, which Athenaeus (2nd/3rd century C.E.) understands to mean citron:

But now, my girl, just take these apples (=citrons). They are fine to look at. Indeed they are, and good too, O ye gods! For this seed has arrived not long ago in Athens, coming from the mighty king. I thought it came from the Hesperides (=nymphs); for there they say the golden apples grow. They have but three. That which is very beautiful is rare in every place, and so is dear.[19]

By stating that these golden apples come from the nymphs, Antiphanes emphasizes the rare and exotic nature of these imported fruits.

The first description of the tree in western literature is in the Enquiry into Plants (Περὶ αἰτιῶν φυτικῶν/De Causis Plantarum) of Theophrastus of Eresos (371–287 B.C.E.), Aristotle’s successor as the leader of the Peripatetic school. Theophrastus reported on the findings of the botanists accompanying Alexander the Great in his conquest of Persian and India (4:4.2):

And in general the lands of the East and South appear to have peculiar plants, as they have peculiar animals; for instance, Media and Persia have, among many others, that which is called the “Median” or “Persian apple.” This tree has a leaf like to and almost identical with that of the Arbutus andrachne (=eastern strawberry), but it has thorns like those of the pear or white-thorn (=wild Syrian pear, Pyrus syriaca), which however are smooth and very sharp and strong… This tree, as has been said, grows in Persia and Media.[20]

Cleary, the citron did not generally grow west of Persia in the 4th/3rd centuries B.C.E., and the author assumes that the average reader will not be familiar with it.[21]

A Fragrant but Inedible Fruit

In addition to describing the tree, Theophrastus describes this strange fruit, which is not edible but has a great smell, making its identity as the citron even clearer:

The “apple” is not eaten, but it is very fragrant, as also is the leaf of the tree. And if the “apple” is placed among clothes, it keeps them from being moth-eaten. It is also useful when one has drunk deadly poison; for being given in wine it upsets the stomach and brings up the poison. Also for producing sweetness of breath, for if one boils the inner part of the “apple” in a sauce, or squeezes it into the mouth in some other medium, and then inhales it, it makes the breath sweet…[22]

This detailed description of the fruit shows that even if citrons were imported during this period, and the readers will have heard of them, most people would never have had access to one, and therefore would find such a description of how they are used new and interesting.

A Cure for Poison

One thing that stands out in his description is the use of the citron to counteract poisoning. This is reflected elsewhere in the descriptions of the citron, and is behind its scientific name, citrus medica.

For instance, the great Roman poet Virgil (70–19 B.C.E.), in book 2 of his Georgic (i.e., “Rustic”), describes this Median fruit:

Media yields the bitter juices and slow-lingering taste of the blest citron-fruit, than which no aid comes timelier, when fierce step-dames drug the cup with simples mixed and spells of baneful power, to drive the deadly poison from the limbs.[23]

An entertaining text along these lines is an anecdote reported by Athenaeus of Naucratis (late 2nd / early 3rd cent. C.E.) about how eating citron saved some convicts, who were being sent to their deaths by an Egyptian official (Deipnosophists 3:28):

He had condemned some men to be given to wild beasts, as having been convicted of being malefactors, and such men he said were only fit to be given to beasts. And as they were going into the theatre appropriated to the punishment of robbers, a woman who was selling fruit by the wayside gave them out of pity some of the citron which she herself was eating, and they took it and ate it, and after a little while, being exposed to some enormous and savage beasts, and bitten by asps, they suffered no injury….[24]

And this result being proved by repeated experiments, it was found that citron was an antidote to all sorts of pernicious poison. But if anyone boils a whole citron with its seed in Attic honey, it is dissolved in the honey, and he who takes two or three mouthfuls of it early in the morning will never experience any evil effects from poison.[25]

Athenaeus next tells how people who were called to dine with the Heraclean tyrant Clearchus would eat citrons before the dinner, since he had a tendency to force his guests to drink hemlock. While these stories are apocryphal, they show that citrons were viewed as a medicinal fruit in the Roman period; they remained so well into the Muslim period.

The Citron Becomes Popular

With its perceived medicinal value, its beautiful smell, and its other uses, in the beginning of the first millennia people in the west start cultivating citron trees. Pliny the Elder, writing in the first century C.E., describes the challenging nature of this endeavor (Natural History 12:7.2):

Because of its great medicinal value various nations have tried to acclimatize it in their own countries, importing it in earthenware pots provided with breathing holes for the roots… but it has refused to grow except in Media and Persia. It is this fruit the pips of which, as we have mentioned, the Parthian grandees have cooked with their viands for the sake of sweetening their breath. And among the Medes no other tree is highly commended.

Although Pliny recorded this failure, we know that the cultivation of citrons outside India and Persia succeeded, and it is during this very period that the citron became firmly ensconced in the Jewish festival of Sukkot as the “fruit of a splendid tree.”

The Jewish Adoption of the Citron

By the first century C.E., the etrog was accessible enough for the average Judean to procure one for the celebration, while at the same time, exotic enough to be considered something special: a fragrant, long-lasting, inedible, and beautiful fruit, used to sweeten the breath and protect one’s health.

Thus, a fruit that was unknown in Israel in the First Temple period, and found only as a luxury import in the Persian periods, became standard for Jews at the very end of the Second Temple period as one of the four species on Sukkot, and remains so to this day.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

September 23, 2021

|

Last Updated

January 9, 2026

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Prof. Dafna Langgut is the Head of the Laboratory of Archaeobotany and Ancient Environments and a Senior Lecturer at the Department of Archaeology and Ancient Near Eastern Cultures at Tel Aviv University. She holds a Ph.D. in archaeology from Haifa University. Langgut specializes in the study of past vegetation and climate based on the identification of botanical remains, which allows her to consider the past relationship between humans and the environment, e.g. human dispersal out of Africa and the beginning of cultivation. Her research also involves the identification of micro-botanical remains (mainly pollen) and macro-botanical remains (wood-charcaol remains) from archaeological contexts, which allows her to address questions related to agricultural practices, diet, plant usage, social stratification, plant migration, ancient gardens and wooden implements. Langgut is also the curator of pollen and archaeobotanical collections at the Steinhardt Museum of Natural History, Tel Aviv University.

Essays on Related Topics: