Edit article

Edit articleSeries

The Practice of Divination in the Ancient Near East

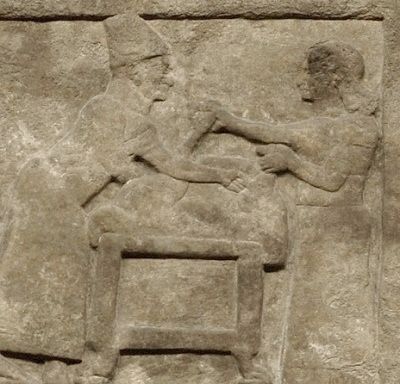

Mesopotamia – Divination by the Liver. Patrick Gray / Flickr

Among other prohibitions, Leviticus 19 commands (v. 26): לא תנחשו “you shall not practice divination.” What is divination? The Online Merriam-Webster Dictionary defines divination as “the practice of using signs (such as an arrangement of tea leaves or cards) or special powers to predict the future.”

This definition gives the impression of divination being simply a magical act, and most people understand the biblical prohibition in this context. But the context of this prohibition should be sought in the ancient Near Eastern cultures surrounding the biblical world, especially in ancient Mesopotamia.

Divination in Ancient Mesopotamia: Seeking Out Divine Manifestation

Divination played a significant role in the religion of ancient Mesopotamia. Thousands of cuneiform tablets from Babylonia and Assyria, dating to the second and first millennia B.C.E., and written in the Akkadian language, deal with divination. These tablets reveal that divination was not primarily about foretelling the future; it was first and foremost a way of seeking the divine manifestation in the universe.

Ancient Mesopotamian gods were conceived of in various ways.[1]

Metaphysical perception – Regarding gods as supernatural entities, not associated with a specific place, similar to the perceptions we know from Judaism and other monotheistic religions.

Natural perception – Associating gods with natural elements in the world, such as water, earth, and especially the celestial bodies.

Cultic perception – Associating a god with its temple and its service where the god is manifest as the cultic image present in that temple.

According to Mesopotamian mythology, humans were created from clay, which is also the basic material of earth in the Mesopotamian environment. Thus, man and the world are made of the same material and one can affect the other. Since the natural world is also one of the aspects of the divine in ancient Mesopotamian thought, the actions that occur in nature could be regarded as manifestations of the divine that influence man. Thus, humans are closely related to the natural perception of the gods.

Humans are also associated with the cult, which is entirely driven by human action, and reflects people’s attempt to relate to the divine. Thus, humans in the Mesopotamian world-view are closely connected to the natural and cultic perception of the deities.

Finding the Divine Messages in the Natural and Cultic Realms

Divination is an attempt to find divine manifestation, especially messages concealed in cult or nature. These messages, which may deal with future events, are usually not self-evident and therefore some action of interpretation is needed in order to comprehend them.

Various forms of divination were practiced in the ancient world; these can be placed on two axes: the axis of “directness” and the axis of “spontaneity.”

The Axis of Directness (from most to least)

- Direct divine oral message, such as one revealed in prophecy.

- Oral messages achieved less directly, e.g., in dreams.

- Entirely indirect messages, not received orally, such as a lunar eclipse or anatomical formations in the liver of a sacrificial sheep.

The Axis of Spontaneity (from most to least)

- Spontaneous phenomena occurring in nature, not provoked by human beings, such as an earthquake or an astral phenomenon.

- Dream incubation, in which a specific message is sought in a dream.

- Extispicy, or the reading of entrails, i.e., finding the divine message by asking an oracular question before the sacrifice of an animal, usually a sheep; the answer is found in its internal organs, usually the liver, after it is slaughtered.

Extispicy: Reading the Entrails of an Animal

Extispicy is both the most indirect and non-spontaneous form of divination. Thus, it requires a complex cultic process in order to provoke it, and a complex interpretive process in order to reveal the divine message that is concealed within the organs of the sacrificial sheep. Although interpreting the shape of a sheep’s liver may seem strange to us, it was normal to those who lived in the ancient Near East, who perceived it as the most sophisticated act of divination.

Offerings in the ancient Near East, including the Bible, are the most important cultic acts that incorporate the relationship between humanity and god. But while in the Bible this action is usually directed only from a person to god, in the ancient Near East the act of offering assumes a mutual relationship: the person brings an offering to a god as an act of gratitude, purification, or for other reasons, and the god, who is present during the cultic act of the sacrifice, also replies to this act by placing a message in this offering.

Gods Writing on Livers

The diviner, after asking an oracular question, and before slaughtering the sheep, prays to the gods of divination, asking them to manifest themselves in the ritual. The divine response may be seen after the sacrificial sheep is slaughtered. It is manifest in the shape of various marks and grooves on the liver and other organs, which are deciphered by the diviner. According to Mesopotamian religious perception these marks are “written down” by the god before the sheep is sacrificed (although they are, of course, there beforehand as well).

Example: A Request of Shamash

Shamash (=the Sun god) and Adad (=the storm god) are especially closely associated with the divinatory act of extispicy. Thus, the following prayer from the seventh century BCE is addressed to the sun-god Shamash, asking him to deliver his message as an answer to an oracular question:[2]

Be present within this sheep, place (in it) an affirmative positive answer, favorable designs, propitious and favorable omens of the oracular query of favorable nature by the command of your great divinity, so that I may see (them)! May (this query) go to your great divinity, O Shamash, great lord, and may an oracle be given as an answer.

It is evident in this prayer that the diviner does not only ask for the message, but that this message is regarded as the god actually being present.

The Groove of the Liver and the Presence of the God

Since the ancients did not perceive the importance of the brain, and felt that the mind with its thoughts, feelings, intentions, and decisions was located in the internal abdominal organs (especially the heart and the liver), these organs of the sacrificial sheep were believed to reveal the decisions and intention of the god.[3]

Indeed, the most important feature of the liver, namely the groove found on the left lobe of the liver of the sheep, was called “the presence,” indicating that this is a mark left by the presence of the deity during the ritual. This is explicitly stated in one of the thousands of written omen entries:[4]

If there is a “presence” (in the liver) – the god was present in the offering of the man.

If there is no “presence” (in the liver) – the god was not present in the offering of the man.

These omen entries serve as further evidence that divination, especially extispicy which is so closely related to the cultic manifestation of the deity, is not only about telling the future or receiving a divine message; rather, it is primarily a means of understanding whether the god was indeed present at the time of offering – an act of communication between man and god – and consequently whether the offering was accepted or not accepted by the god (a concern that is the subject of the biblical Cain and Abel story as well).

Divination Education

The omen entries cited above are two of many thousands of such omens. These omens are always formulated as conditional sentences, consisting of a protasis, where the physical condition is described, and an apodosis, where the prediction to this condition is given. There are features in the liver that usually refer to a certain theme in the prediction.

Thus, as we have seen above, a certain groove on the left lobe of the liver of the sacrificial sheep was called “the presence,” and was related to predictions regarding the god’s presence in man’s life. Likewise, another groove on the left lobe of the liver was called the “path,” predicting events related to the course of live, journeys, and especially military campaigns (where the army proceeds on a “path”). For example, an omen entry refers to the condition where there are two “path”-grooves instead of the normal single “path,” indicating a favorable prediction:[5]

If there are two “paths” – the one who is going on a campaign will complete his campaign.

The diviner had to study these omens, and then match the various markings on the actual internal organs of the sacrificial sheep with the hypothetical omens, and arrive at the positive or negative answer to the oracular question he posed. The education of the diviner, included clay models of sheep livers and other internal organs, often inscribed with their predictions.

Several such liver models dating to the middle of the second millennium BCE, some of them inscribed with Akkadian predictions in cuneiform, were excavated in the city of Hazor in modern Israel, showing that the Mesopotamian divinatory lore traveled in antiquity to the Land of Israel as well.

The Problem of Divination

The biblical prohibition in Leviticus 19, when seen in its ancient Near Eastern context, is not only against a popular superstition about foretelling the future. As seen above, divination was conceived as a means of communication with the divine realm, and was closely related to sacrificial rituals. Therefore, the biblical prohibition addresses a fundamental perception of ancient Near Eastern cult and religion, and even of the ancient Near Eastern god himself.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

May 9, 2016

|

Last Updated

January 31, 2026

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Prof. Uri Gabbay is Associate Professor of Assyriology at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem’s Department of Archaeology. He received his Ph.D. in Assyriology from the Hebrew University in 2008. He edited (with Shai Secunda) the book Encounters by the Rivers of Babylon: Scholarly Conversations between Jews, Iranians and Babylonians in Antiquity.

Essays on Related Topics: