Edit article

Edit articleSeries

The Zer

Moses setting up the Mishkan. Print maker: Jacob de Later Dating 1696 – 1709 Rijksmuseum.nl

The word זֵר (zēr) occurs ten times in the Torah, always in the context of the tabernacle, as the term for a feature of a major cult object.[1] A זֵר adorns:

- The ark (Exod 25:11, 37:2),

- The table (25:24, 37:11),

- The table’s מסגרת (25:25; 37:12),

- The incense altar (30:3, 4; 37:26, 27).

In all four cases, the text specifies that the זֵר is made of gold (זהב) and is situated “around” (סביב) the object it adorns (25:11, 24, 25; 30:3; 37:2, 11, 12, 26). But this is not sufficient to indicate the form of the זֵר and where it is located: top, bottom or middle?

The Methodologies to Identify the Term זֵר

But how can we identify the meaning of this term? One approach is to relate the biblical term to similarly sounding words in Hebrew or related languages—an etymological argument. Another approach is to look at how the ancient translations of the Bible understood this term—perhaps the correct tradition was known by them. Scholars also argue from material culture, looking at ancient artifacts to find a parallel that would fit with the biblical context. In this case, this third approach, relying on material culture, is more fruitful than the etymological approach or relying on the ancient translations.

Etymological and/or Traditional Explanations

Ancient and medieval biblical interpreters offered many different possibilities for what the זֵר might be. Below are two charts surveying the various positions and their bases.

Pre-Modern Interpretations

| Translation | Parshan | Notes |

| 1. Lip (שפה)I[2] | Attributed to Aquila[3] | This translation appears to be a contextual guess; it envisions a projection encircling the ark’s top. |

| 2. Crown (כלילא or כתר), |

Targum Neofiti,Fragmentary Targum V, the Peshitta,[4] R. Shimon Bar Yochai in Exodus Rabbah (34:2)[5] | This translation equates the root of זֵר with that of נזר (crown). |

| 3. Thing that surrounds | Menahem ibn Saruq and Jonah ibn Janah[6] | Equating זֵר with the verbal form זֵרִיתָ (Pss 139:3).[7] |

| 4. Gold coating | Bekhor Shor followed by Hizkuni.[8] | Arguing from context; the term applies to elements that otherwise lack specific instructions to coat with gold.[9] |

| 5. Enclosure | Midrash HaGadol and Ralbag[10] | The one on the ark holds the kapporet in place; the one on the table holds the objects on the table; and the זֵר of its מסגרת holds the top of the table itself.[11] |

| 6. Transliteration (זיר or דיר) | Targum Onqelos and Pseudo-Jonathan | They are transcribing the word without translating it, probably reflecting that they did not know its meaning. (Neither term has any meaning in Jewish Aramaic that makes sense in this context.[12]) |

Modern Scholarly Suggestions

Like their pre-modern predecessors, modern Bible scholars have also offered a panoply of overlapping translations for this term, mostly based on Semitic etymologies.

| Translation | Exegete | Notes |

| 1. Circlet (or Border) | The Brown-Driver-Briggs dictionary (BDB) | They derive this translation from זור III (“press down and out”). |

| 2. Frame (or Border) | The Hebrew and Aramaic Lexicon of the Old Testament (HALOT) | They derive this not from a Hebrew root, but from Akkadian zirru, meaning “reed hedge.”[13] |

| 3. Encircling Rim (or Border) | Yehoshua Grintz | Accepting the pre-modern suggestion, “lip.” As support, Grintz notes that ḏr in Egyptian means “boundary” and “enclosing wall.”[14] |

| 4. Flowery Adornment[15] | Umberto Cassuto | Cassuto’s suggestion is surprisingly specific both in position and its form, yet he nowhere explains his reasoning for this interpretation. |

| 5. Ring-Fastener | Benno Jacob | Arguing that the זֵר possesses the same status as the rings and poles, he infers that the purpose of each זֵר is to fasten the rings to the object.[16] |

| 6. Ring-Supporter | William Propp | In this model, the זֵר is positioned around the middle of the ark’s height and serves the structural purpose of supporting the rings below it.[17] |

Summary: Etymology vs. Archaeology

This survey demonstrates that a compelling identification of the זֵר has not been reached and suggests that etymology cannot lead to such an identification. What none of the surveyed exegetes appear to have done, however, is to search ancient Near Eastern material culture and examine artifacts resembling the ark, the table and the incense altar for features that correspond to the זֵר.

The Septuagint and Classical Greek and Roman Material Culture

The ancient Greek translators responsible for the Septuagint (LXX), seemingly arguing from their experience with decorative features on buildings and objects in the Greco-Roman world, translate the זֵר as:

- kumatia strepta / strepta kumatia / strepton kumation (“twisted cymatia/cymatium”)[18]for the ark, the table, and the table’s מסגרת,

- streptein stephanein (“twisted crowning”)[19] for the incense altar.[20]

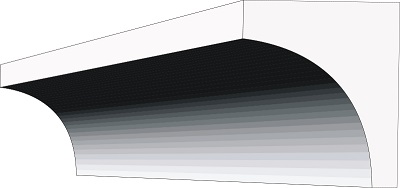

The Greek word kumation is an architectural term denoting a type of molding. It comes from the word “kuma” meaning “wave” or “swelling,”[21] and probably refers to a projection of some kind.[22] In Ancient Greek inscriptions it refers to what are known today as “ovolo” (convex quarter-round) and “cyma reversa” (double-curved with the convex part projecting beyond the concave part) moldings[23]

|

|

The word the Septuagint uses to render the זֵר of the incense altar, stephanei[26] is the same term used to render מעקה in Deut 22:8—an addition to a roof to prevent people from falling off it. The term means “anything that surrounds or encircles the head, etc., for defense or ornament.”[27] The word’s range of meanings, along with the Septuagint’s use of it to translate מעקה—indicate that the translator envisioned the זֵר, at least in the case of the incense altar, as located at the top of the object.[28]

In all four cases, the translator adds the adjective streptos, “twisted” or “wreathed.” Since the LXX also uses this term for גדִלים in Deut 22:12, a word designating some sort of attachment to a garment,[29] he seems to have associated the word זֵר with the root שזר, a fabric-related root peculiar to the Exodus tabernacle passages, [30] and usually understood as carrying the sense of “spin” (thread).[31]

The description “twisted” is somewhat vague, but we may be able to clarify what these authors have in mind by looking at a passage in the Letter of Aristeas (51–82)[32] that describes a table granted by Ptolemy Philadelphus to the Temple in Jerusalem. The table, which is said (56) to be constructed according to the Jewish scriptures (i.e. Exod 25:23–30), has a crowning (=מסגרת) with twisted cymatia (=זֵר), which take the form of ropes[33] with precious stones interwoven between them (58-60).

This more detailed description accords with the Septuagint and immediately brings to mind the guilloche, a.k.a., plait-band pattern, which decorates moldings – particularly convex moldings – on Greek architecture in all periods,[34]and is seen, for example, in the Erechtheum.

The Zer as the Ancient Egyptian Cavetto Cornice: An Archaeological Solution

The LXX interpretation, as expected, makes use of the translator’s contemporaneous material environment. But these writers were mainly aware of classical Greek and Roman architecture and design, and this is not the right period to search in order to identify the referent in the more ancient biblical text. We need to sift through more ancient pre-classical artifacts.

More specifically, the search should begin with the Egyptian material. As scholars have noted, the descriptions of the tabernacle, its components, and its furniture reflect first and foremost Egyptian craftsmanship.[36] Furthermore, Egyptian furniture held a prized status throughout the ancient Near East, and could serve as a proper model for the tabernacle.[37]

The Cavetto Cornice

I believe that the זֵר is the cavetto cornice, a common element in Egyptian architecture and crafts that is at least as old as the Third Dynasty.[38] It consists of a concave molding with a quarter-circular profile that surrounds the top of an object or structure.

a. Ark

The ark is best understood as a portable wooden chest made in typical Egyptian style. Extant chests from ancient Egypt reveal parallels to almost every detail of the ark as described in Priestly and other biblical texts.[40] The cavetto cornice commonly appears on portable wooden boxes and chests from the Fifth Dynasty onwards.[41] Such items from the Eighteenth Dynasty alone include a box with a shrine lid, several boxes from the tomb of Yuia and Thuiu, and several objects from the tomb of Tutankhamun.[42]

|

|

Like the biblical זֵר, the cavetto cornice could be made of gold. This is illustrated by a beautiful specimen found on an obsidian box from Byblos bearing the name of the 12th Dynasty Pharaoh Amenemhet IV (c. 1798–1790 BCE).[45]

|

|

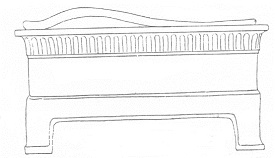

b. Table

The cavetto cornice also adorned ancient Egyptian wooden tables. Depictions of tables with cavetto cornices already appear in the Sixth Dynasty tomb of Mereruka (c. 2340 BCE), and two actual examples, from the Seventeenth and Eighteenth dynasties, are extant.[48]

These tables display additional similarities to the table of the tabernacle as described in the Pentateuch: one is known to be made of acacia wood and sports proportions of approximately 2W x 3H x 4L (see Exod 25:23, 37:10).[50] And both have a horizontal frame of stretchers connecting the legs at about mid-height, which may correspond to the table’s מסגרת (Exod 25:25[x2], 27; 37:12[x2], 14). Depictions of similar tables with cavetto cornices appear in several Phoenician artworks from the first millennium BCE.[51]

c. The Incense Altar and Ancient Stone Altars

Incense altars were not used in ancient Egypt,[52]and I am unaware of any extant examples of such objects from elsewhere in the ancient Near East. However, in Egypt, large, stone altar platforms were usually furnished with typical cavetto cornices,[53] as were some of the small, Syrian-influenced horned stone altars that appear in the Hellenistic period, such as the one at Karnak.[54]

Not surprisingly, the same is true of many monolithic stone incense altars from ancient Israel.[56] [See Appendix for more discussion.]

The Cavetto Cornice is the Biblical זֵר

The cavetto cornice appears to be the only feature of ancient Near Eastern material culture that corresponds in every way with the biblical זֵר. Thus, the word זֵר can confidently be provided with a definition, even if it cannot be explained etymologically. Indeed, the most fruitful way of trying to understand the discussion of the tabernacle and other ancient artifacts in the Bible may be the way of archaeology and not etymology.

Once we understand the meaning and context of the biblical passages, we can appreciate God’s command to Moses about how to build the mishkan. Egyptian style furnishings represent the height of luxury in the ancient Near East, and for that reason the mishkan should be furnished in the Egyptian style, the highest available.

Appendix

The זֵר and the כַּרְכֹּב of Altars

As stated above, the incense altar mentioned in the Torah has no parallel in Egyptian material culture, and the Torah does not mention the need for a זר when describing the main altar. Nevertheless, archaeological evidence points to the fact that Israelite stone altars often did include this feature. In fact, many of these altars even display additional features of the incense altar as described in the Pentateuch: specifically, proportions of approximately 1W x 1L x 2H, and horns (see Exod 30:2, 37:25).

On the most carefully made specimens, the flaring of the cornice appears to be concave, indicating that the constructors were aiming for a cavetto-type cornice. This is most clear on the two altars from the temple in Arad; on these, however, the cornice protrudes from a groove and so its edges are in line with the sides of the altar.

The Band and the כַּרְכֹּב

The altars are often encircled at mid-height or above with a conspicuous wide, rectangular-profile band.

|

|

| Altars at the Arad temple.[58] | |

Gitin’s Interpretation: Band = זֵר, Cornice = כַּרְכֹּב:

Noticing this feature, Seymour Gitin suggests equating this band with the זר and the cornice with the כַּרְכֹּב casually mentioned in Exodus (27:5 = 38:4) as a feature of the bronze altar.[59]

Exod 27:5

וְנָתַתָּ֣ה אֹתָ֗הּ תַּ֛חַת כַּרְכֹּ֥ב הַמִּזְבֵּ֖חַ מִלְּמָ֑טָּה

Set it (=the meshwork) underneath the karkov of the altar on the bottom.

Exod 38:4

וַיַּ֤עַשׂ לַמִּזְבֵּ֙חַ֙ מִכְבָּ֔ר מַעֲשֵׂ֖ה רֶ֣שֶׁת נְחֹ֑שֶׁת תַּ֧חַת כַּרְכֻּבּ֛וֹ מִלְּמַ֖טָּה עַד־חֶצְיֽוֹ:

He made for the altar a grating of meshwork in copper, extending below, under its karkov, to its middle.

But contrary to Gitin’s suggestion, the text implies that the כַּרְכֹּב is at the altar’s middle, not its top.

Eichler’s Interpretation: Cornice = זֵר, Band = כַּרְכֹּב

Considering the evidence from the verses, that the כַּרְכֹּב is in the middle, combined with my identification of the זֵר as the cornice in the main article, I believe the reverse of Gitin’s theory is more likely. The band should be equated[60] with the כַּרְכֹּב, and the cornice should be equated with the זֵר.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

February 23, 2015

|

Last Updated

November 21, 2025

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Prof. Raanan Eichler is an Associate Professor of Bible at Bar-Ilan University in Israel. He received his Ph.D. from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and completed fellowships at Harvard University and Tel Aviv University. He is the author of The Ark and the Cherubim (Mohr Siebeck, 2021) and many academic articles.

Essays on Related Topics: