Edit article

Edit articleSeries

Tiberius Alexander: The Jewish General Who Destroyed Jerusalem

Proclaiming Claudius Emperor, Lawrence Alma-Tadema 1867

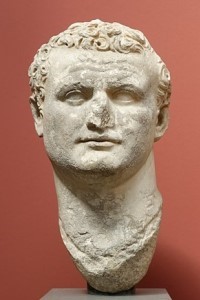

Titus, son of Emperor Vespasian, is widely known as the man who conquered Jerusalem in 70 C.E. Fewer readers, however, will know the name of the formidable military commander whom Vespasian chose to assist his inexperienced son in this campaign: Tiberius Julius Alexander, a highborn Egyptian Jew who ranks as one of the most eminent figures in Jewish history.[1]

Tiberius’ Influential Family

Tiberius’ family had deep roots in Egypt’s Fayum region (an oasis ca. 60 miles south of Cairo), where many Jewish communities thrived since at least the third century B.C.E.[2] His father, Alexander, was the younger brother of none other than Philo, the prominent Jewish philosopher in Alexandria. As we will see, Tiberius appears as a disputant in Philo’s elaborate philosophical dialogues.

An affluent and important political figure in Egypt, Alexander was the guardian (epitropos) of Antonia the Younger, the daughter of Mark Antony and mother of the Emperor Claudius. He also served as Alabarch—a title that may derive from Arabarch, “governor of the Arab frontier” and a position normally held by Jews—with oversight of customs and taxation in Alexandria.[3] Emperor Caligula apparently saw Alexander as a significant political threat and had him imprisoned. Following Caligula’s assassination in 41 C.E., Alexander’s friend Claudius became emperor and had him released.

Alexander was also well connected in Jerusalem and appears to have had especially good relations with the Temple. According to Josephus, he made generous donations to overlay nine Temple-gates with gold and silver:

Jewish War 5 Now the magnitudes of the other gates were equal one to another; but that over the Corinthian gate, which opened on the east, over against the gate of the holy house itself, was much larger. For its height was fifty cubits: and its doors were forty cubits: and it was adorned after a most costly manner; as having much richer and thicker plates of silver and gold upon them than the other. These nine gates had that silver and gold poured upon them by Alexander, the father of Tiberius. Now there were fifteen steps, which led away from the wall of the court of the women to this greater gate: whereas those that led thither from the other gates were five steps shorter.

In 70 C.E. these gates were destroyed, and as discussed below, his son Tiberius may have had a direct hand in their destruction.

Marcus Julius Alexander and Berenice

Marcus Julius Alexander, the younger brother of Tiberius, was an influential merchant and entrepreneur like his father. He received the hand of Berenice (Berenike), daughter of King Agrippa I of Judah, but died shortly after.

Berenice is an impressive and fascinating figure in her own right. She went on to wed first Herod V, King of Chalcis, then Polemon II, King of Pontus and Cilicia—who even had himself circumcised for her!—although she deserted him soon thereafter.

The Jewish princess eventually caught the attention of Titus (who was eleven years her younger) after his victories in the Galilee. Although she became his fiancée and later accompanied him to Rome, the populace did not accept her, and Titus sent her away—twice.[4]

Tiberius Before 70 C.E.

Unlike his younger brother Marcus, Tiberius pursued a political career, which, in the Roman Empire, was closely connected to the military.[5] Indeed, Tiberius’ family belonged to the equestrian order, whose members, the equites (“equestrians” or “knights”), enjoyed a status second only to the Roman Senate.

Governor of Judea

In 42 C.E. (a year after Claudius became emperor), Tiberius began his career as commander (epistrategos) of the Thebaid, one of the three regions of Roman Egypt. Philo implies that he was part of an embassy to Rome (On the Rationality of Animals 54), which may have occurred earlier.

From 46-48 C.E., he served as the procurator (or governor) of Judea. During his tenure, Judea suffered from a famine, and Helena, the queen mother of the Parthian vassal state of Adiabene (who had converted to Judaism), generously paid for grain to be brought from Egypt and figs from Cyprus (although the Talmud ascribes this deed to her son Monobaz II).[6]

It was also during these years that Tiberius, according to Josephus (Antiquities 17), ordered the “crucifixion” of Jacob and Simon. Following in the footsteps of their father Judas of Galilee, the brothers had staged a religio-nationalist revolt as a response to Roman taxation. By taking decisive punitive actions, even against his fellow Jews, Tiberius demonstrated his allegiance to Rome.

But as governor of Judea, he also acted in the interest of his Jewish kin (and likely with the support of the High Priest), since these rebels posed a serious threat to the future of the province and its population. Indeed, Josephus saw them as part of the same radical factions responsible for the later Jewish rebellion (66–74 C.E.) that brought the destruction of the Temple.

Distinguished Mission to Armenia

Between his tenure as governor of Judea and his command of the army that laid siege to Jerusalem, Tiberius rose to the highest military ranks, although the details are largely unknown. An inscription from Tyre refers to him as the governor of Syria (procurator provinciae Syriae) and proclaims him to be the patron of Tyre.[7]

A passage from the Annals[8] of Tacitus (ca. 56 C.E.– ca. 120 C.E.) commemorates Tiberius’ participation in a prestigious mission to Parthia. The revered Roman historian calls him an inlustris eques Romanus (“a distinguished

Annals 15.28 On the day appointed, Tiberius Alexander, a distinguished Roman knight, sent to assist in the campaign, and Vinianus Annius, Corbulo’s son-in-law, who, though not yet of a senator’s age, had the command of the fifth legion as “legatus,” entered the camp of Tiridates, by way of compliment to him, and to reassure him against treachery by so valuable a pledge; each took twenty horsemen.[9]

We learn from the text that Tiberius was one of the leading officers in the East Roman Army commanded by Corbulo in Armenia. Noteworthy is that Tacitus calls him a Roman but has nothing to say here (or in his Histories 1.11; see below) about Tiberius being a Jew. Either he deemed Tiberius’ Jewishness irrelevant to his account or was not aware of it.

Governor of Egypt

In 66 C.E., Nero appointed Tiberius to the extraordinarily high office of Egyptian procurator, commanding two legions. This was the same year that the First Jewish-Roman War began, which precipitated unrest between Jewish and Greek populations in Egypt.

In his Histories, Tacitus describes the obstacles Tiberius faced in Egypt. The land was “difficult of access, exporting a valuable corn-crop, yet divided and unsettled by strange cults and irresponsible excesses, indifferent to law and ignorant of civil government.” It was essential to keep Egypt “under the control of the imperial house, and it was ruled at the moment by Tiberius Alexander, himself an Egyptian” (Hist. 1.11).

Notice that the Roman historian refers to Tiberius not only as loyal to Rome but also as an Egyptian. Scholars from Victor Tcherikover to Louis Feldman have summoned this account to argue for Tiberius’ putative “apostasy,” an issue to which we will turn below.[10]

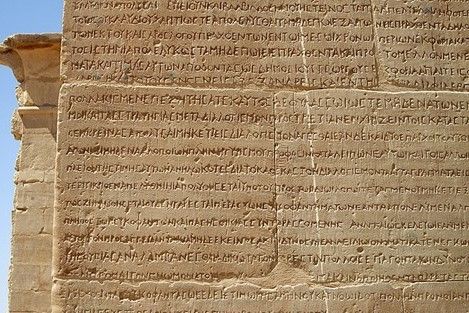

In 68 C.E., immediately after Galba succeed Nero as emperor, Tiberius issued an edict. Inscribed in Greek on the walls of the Hibis temple (in the el-Khargeh Oasis), it announces a new policy of “benefaction” (euergesia) to win the favor of the new emperor and of the local populace. “Ever since I stepped foot in this city, I’ve been lobbied by pressure groups” (5-6). A new day had now dawned, and Galba’s accession permitted Tiberius, as Egypt’s governor, to pursue positive reforms and a lighter load for his subjects.[11]

|

|

| The Edict of Tiberius Alexander | The Hibis Temple |

But that same year, Tiberius had to intervene in violence between Greeks and Jews. In his Jewish Wars (2.490–98), Josephus recounts at length how he responded to an episode as well as Jewish threats of retaliation.[12]

Instead of immediately sending soldiers, Tiberius is said first to have warned the Jews to not respond. When his warning went unheeded, he dispatched his two Roman legions along with 5,000 Libyan auxiliaries, authorizing them to slaughter, plunder, and torch the houses of the Jews. Josephus claims that 50,000 of his fellow Jews, including infants, were killed before Tiberius relented and stopped the massacre.

The casualties that Josephus claims are likely inflated. Indeed, his whole account of the episode smacks of polemics against Tiberius, whose influence the Jewish general and historian seems to have resented (see below).

Tiberius and the Flavians

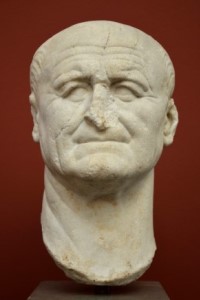

Egypt served as an important breadbasket for the region, and Tiberius was in a position to exercise considerable influence in imperial politics. In 69 C.E., the military commander Vespasion was occupied with the revolts in Judea, but he formed an alliance with Tiberius in the hope of becoming emperor.

Tiberius, as Egypt’s governor, ordered his legions and the general population to swear allegiance to Vespasian. His action set the precedent for other legions to follow suit in the following weeks. With the support of Egypt and the eastern armies, Vespasian then left Judea in the hands of his son Titus and set out for Rome. He stopped first at Alexandria, where he was received with pomp and splendor.

Without the support and direct intervention of this Egyptian Jew, Vespasian never would have become emperor. This is a remarkable—yet widely unrecognized—fact in the modern remembrance of the Roman past.

Participation in the Temple’s Destruction

Titus, barely 30 years old, was not up to the task of conducting the Judean campaign alone, so Vespasian requested that Tiberius serve as his son’s counselor and chief-of-staff. In his Jewish Wars, Josephus identifies two reasons for the appointment to this position of second-in-command. Tiberius had not only wisdom of years and proven competence in handling similar crises, but more importantly, he had been Vespasian’s earliest ally, even “when things were uncertain, and fortune had not yet decided in his favor” (5.45–46).[13]

Josephus presents Titus witnessing how his endeavors to “spare a foreign temple” brought about losses for his soldiers, and therefore orders the gates of the Temple to be burned (Wars 6.228)—the same gates that Tiberius’ father Alexander had once paid to be plated with precious metals (5.205). Yet after the fire spreads throughout the city for two days, Titus instructs his men to quench it (6.243).[14]

Meanwhile, at a strategy council, Titus speaks out emphatically against a suggestion to destroy the Temple, and Tiberius together with several others support the motion (Wars 6.236–243). That the Temple is nevertheless destroyed is said to be the work of a lone Roman soldier, acting not on any orders but propelled by “a certain divine fury” in keeping with a punitive fate long ago decreed by God.[15] The insistent orders of Titus to extinguish the conflagration and his efforts to regain control of his violence-possessed legions were to no avail (6.249–259). In this manner, Josephus exonerates both Titus and Tiberius from any culpability in the destruction of the Temple.

An alternative account from the fourth century Christian historian Sulpicius Severus presents Titus ordering the destruction of the Temple. Severus may have had reliable sources (not least Tacitus) for this claim, and scholars have long embraced it, especially given the pro-Flavian slant in Josephus’ Wars.[16] If Titus had in fact ordered the Temple’s destruction, Tiberius may, or may not, have opposed his decision.

After 70 C.E.

Just as the relationship with Berenice had proved to be politically and financially advantageous, Titus probably kept Tiberius as a close advisor after Tiberius served as his general during the campaign against Judea. (Recall that Berenice, who had been married to Tiberius’ brother before he died, also accompanied Titus to Rome but, because she was not accepted there, was sent away twice.)

A fragmentary papyrus, dating to after 70 C.E., calls Tiberius preafectus praetoria. If reliably reconstructed, it would mean that Vespasian or Titus appointed him Commander of the illustrious Praetorian Guard, making Tiberius the highest-ranking Jew in all of antiquity.

The British papyrologist Sir Eric Gardner Turner wrote regarding Tiberius’ position in Rome:

Such hob-nobbing with the triumphales must surely mean that [Tiberius] had his share of ornamenta triumphalia in the triumph of A.D. 71 when the Table of the Shewbread and the Seven-Branched Candlestick [from the Jerusalem Temple] were paraded through the streets of Rome.[17]

The names and honorific titles of Tiberius and his father would have been inscribed on the triumphal statues at the Forum. Juvenal’s first Satire, composed decades after the death of Tiberius, may refer to this monumental inscription,[18] and in keeping with his xenophobia, he invites those searching for afternoon amusement in Rome to deface it:

…and those triumphal statues where some Egyptian Arabarch has had the nerve to set up his titles. At his image it’s not enough to just take a piss. (Satire 1:129–131)[19]

Why Tiberius was forgotten in Jewish history is clear: he was a powerful and venerated figure who had allied himself with the Romans, was partially responsible for putting down the Great Rebellion, and had had a direct hand in the destruction of the Temple. Ironically, that Tiberius does not figure even more prominently in the annals of Roman history may be partially explained by his Jewish identity.[20]

A Religious Apostate and Political Turncoat?

Everything we know about Tiberius is that he performed his duties as a shrewd soldier-statesman and that he achieved his position of power through demonstrations of undivided loyalty to Rome. Although his worldview would have been more cosmopolitan than those in Jerusalem who resisted Roman arms, we should probably not classify him, with Turner, as an “ex-Jew” who went to war against “his former Jewish brethren.”[21]

On one hand, his father was an esteemed donor to the Jerusalem Temple, and his brother married the Judean princess Berenice. On the other hand, he had proved that he was impartial in punishing Judeans/Jews. Both facts made him, repeatedly, an ideal candidate for the Romans in their quest for one who could best represent their interests in Egypt and Judah. Had he openly severed all ties to the Jewish people, he would have been politically ineffective and uninteresting to Rome.

Tiberius’ Piety

Like his father, Tiberius was well educated in both Jewish and Greek literature as well as Roman and Egyptian history and culture.[22] His family moved with ease in imperial circles, both in Alexandria and Rome. Yet Tiberius himself seems to have been willing to go to greater lengths than his father and uncle in demonstrating allegiance to Rome.

As a high-ranking commander, Tiberius would have likely participated in the cult of the war camp, where Rome’s official festivals were celebrated in absentia.[23]

The edict he issued in Egypt during the reign of Galba (mentioned above) praises the emperor with solar divine imagery that had a long legacy in Egypt. In keeping with its publication on the wall of an important temple, the edict concludes by praising the “gods who have reserved the safety of the world for this most sacred time” (8–10).

In an official document preserved in a fragment papyrus (CPJ 418a), Tiberius expresses gratitude to Serapis son of Ammon:

Tiberius Alexander ... the Emperor... the city. The crowds ... all the hippodrome... that in health, lord Caesar, . . . Vespasian, the one savior and benefactor, ... you in its rising ... guard him for us ... lord Augustus, benefactor, Sarapis ... Son of Ammon and . . . we give thanks to Tiberius... Tiberius... divine Caesar... that he may be (?) well ... the divine Caesar Vespasian ... lord Augustus Vespasian ...[24]

Finally, at the Dendera Temple complex, an image of Claudius offering flowers to two gods stands next to an inscription mentioning Tiberius along with higher-ranking officials.[25] The wording suggests that all of them sponsored the making of the image.[26]

Polemics in Philo and Josephus

Philo presents his nephew as a sophisticated thinker who can philosophize with the best of them, and even fictively attributes his own work On the Rationality of Animals to Tiberius.[27] Philo then “responds” to his nephew’s claim by demonstrating that animals are not rational and therefore do not have souls. According to Maren Niehoff, the reason Philo uses Tiberius Alexander as a character in this work is because with his nephew’s name he could get attention from philosophers in Rome who were at that time disputing whether animals are rational creatures.[28]

In his On Providence (extant only in Armenian), he has a dialogue with a certain Alexander, who doubts that God is providential. This figure may represent his nephew Tiberius Julius Alexander, who in his lifetime would have gone by the name Alexander rather than Tiberius. In both cases, Philo has depicted Tiberius as an impressive philosopher in his own right.

Although Philo may have disapproved of (some of) his nephew’s actions, many Jews in his assimilated circles would not have been troubled by his participation in “pagan” cults and culture. These activities should not be viewed as evidence for Tiberius’ abandonment of his “Jewishness.” Indeed, they conform to the expectations for a figure partaking in public life in Egypt and the Roman Empire. As Paula Fredriksen observes: “Every time we encounter a Jewish ephebe, a Jewish town councilor, a Jewish soldier, a Jewish actor, or a Jewish athlete, we find a Jew identified as a Jew who obviously spent part of his working day demonstrating courtesy to gods not his.”[28]

Turning from Philo the philosopher to Josephus the historian, the Wars in 75 C.E. were written in Rome, perhaps under the patronage of Vespasian and Titus (see his Vita 358-64). If so, we could explain why his history is consistently positive in its portrayal of these two Roman rulers. Josephus could allow himself to be polemical in his presentation of Tiberius’ earlier tenure in Egypt (see above under “Participation in the Temple’s Destruction”).

The reason is that Tiberius acts alone, and therefore Josephus’ unfavorable account would not have implicated Vespasian and Titus. However, he could not afford to be critical of Vespasian’s decision to appoint Tiberius to second-in-command, or even of Tiberius’ involvement in the events of 70 C.E., since that would have implicated the Roman emperors.

The Antiquities were published in ca. 94 C.E., long after Vespasian, Titus, and Tiberius were dead. And they are more critical of Tiberius. Thus, the Wars claim that Tiberius did “not alter the ancient laws and kept the nation in tranquility” (2.220). However, the Antiquities explicitly contradict this earlier statement. They assert that Tiberius “did not remain steadfast in his ancestral customs” and compare him unfavorably with his more pious father, Alexander (20:101–103).

Hybrid Identity

The polemics against Tiberius in Josephus and Philo do not serve as evidence that he abandoned the “Jewish people” by serving on the Roman side in 70 C.E., as many modern scholars have claimed. He would not have been alone in regarding his service as neither political disloyalty nor religious apostasy. To the contrary, most may have viewed his dichotomous or “hybrid” identity as an important advantage.[29]

The same goes for others. Berenice apparently saw no conflict between her allegiance to her people, whom she represented and for whom she risked her life, and her love for Titus, the conqueror of Jerusalem. Not least, Josephus proudly describes the favor he won with Vespasian and later with Titus, whom he accompanied on his triumphal return to Rome. Such boundary crossing was perhaps disconcerting for some, yet it was also necessary to survive in an age of imperial rule.

It might be tempting to blame Jerusalem’s fate in 70 C.E. on a Jewish “turncoat.” But there can be doubt about who the real culprit is: a vocal and belligerent faction of rebels and revolutionaries. Their members stood in a long tradition of imprudent resistance, going back to the days of Jeremiah. With an attitude of “give me liberty, or give me death,” these radicals were willing to sacrifice everything for the sake of Jewish freedom,[30] and they lost. The lessons for the present day are all too clear.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

July 28, 2024

|

Last Updated

September 24, 2025

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Prof. Jacob L. Wright is Professor of Hebrew Bible at Emory University’s Candler School of Theology. He holds a doctorate from Georg-August-Universität, Göttingen. Wright is the author of Why the Bible Began: An Alternative History of Scripture and Its Origins, which won the 2023 PROSE Award and was on the “best-of” lists for 2023 from The New Yorker and Publishers Weekly. He is author of several other award-winning books and the editor of many others.

Essays on Related Topics: