Edit article

Edit articleSeries

Joshua Circumcises Israel in Response to Egypt’s Scorn

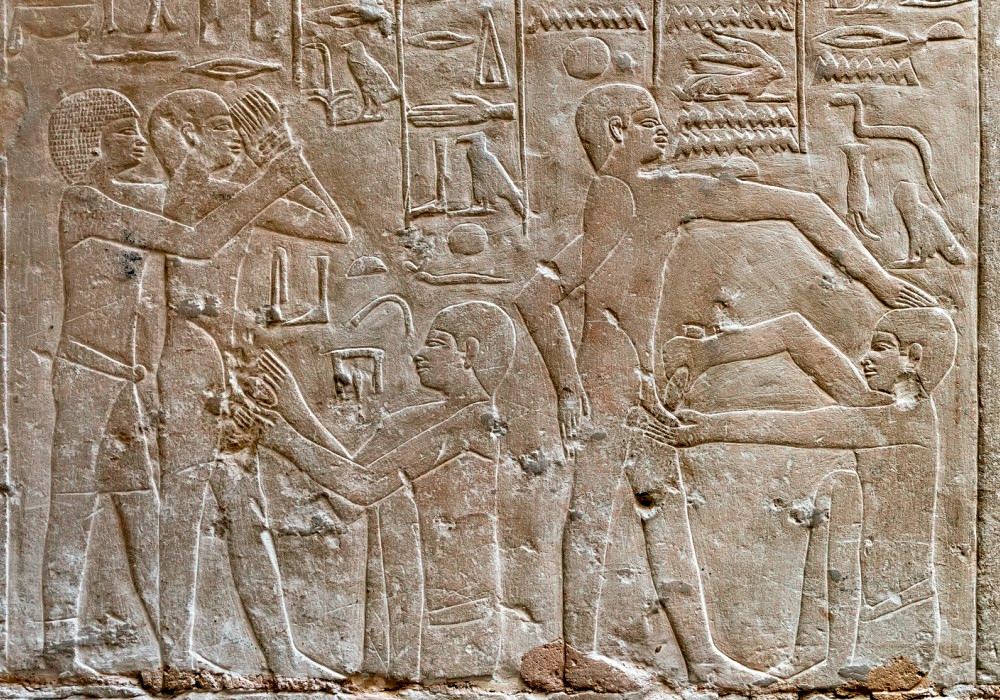

Scene of Circumcision in ancient Egypt. Old Kingdom, 6th Dynasty, reign of king Teti, ca. 2345-2333 BC. Tomb of Ankhmahor, Saqqara necropolis. Flickr, kairoinfo4u.

After leading the Israelites into the land, Joshua circumcises them at God’s command:

יהושע ה:ג וַיַּעַשׂ לוֹ יְהוֹשֻׁעַ חַרְבוֹת צֻרִים וַיָּמָל אֶת בְּנֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל אֶל גִּבְעַת הָעֲרָלוֹת.

Josh 5:3 So Joshua made flint knives and circumcised the Israelites on the Hill of the Foreskins.

After explaining why the Israelites had been uncircumcised in the first place (vv. 4-7), the narrative continues:

יהושע ה:ט וַיֹּאמֶר יְ-הוָה אֶל יְהוֹשֻׁעַ הַיּוֹם גַּלּוֹתִי אֶת חֶרְפַּת מִצְרַיִם מֵעֲלֵיכֶם וַיִּקְרָא שֵׁם הַמָּקוֹם הַהוּא גִּלְגָּל עַד הַיּוֹם הַזֶּה.

Josh 5:9 Then YHWH said to Joshua: “Today I have removed the disgrace [Heb. galoti] of Egypt from upon you.” He called the name of the place Gilgal until this day.

What is this “disgrace of Egypt”?

Disgrace of Wandering (Abarbanel)

Don Isaac Abarbanel (1437-1508) connects this disgrace to the story of the scouts in Numbers 13-14:

ואחשוב אני בזה שלפי שהלכו ישראל במדבר ארבעים שנה היו המצרים אומרים “מבלתי יכולת ה’ להביאם אל הארץ אשר נשבע להם וישחטם במדבר” (במ’ יד, טז). ועתה כאשר העבירם האל ית’ אל הארץ והיו ישראל בגלגל אמר, “היום גלותי את חרפת מצרים מעליכם” כי יאמרו שכבר באתם אל הארץ.

My opinion on this matter is that since the Israelites travelled in the wilderness for forty years, the Egyptians said, “Because of the inability of the Lord to bring them into the land that he swore to them he slaughters them in the wilderness” (Num 14:16). Now, when God brought them into the land and the Israelites were present at Gilgal, God said, “Today I have removed the insult of Egypt from upon you,” for they will (now) say (=admit) that you have already entered the land.

According to Abarbanel, Israel’s forty-year presence in the wilderness was a national humiliation which finally came to an end with the Israelites’ entrance into the land at Gilgal.[1] But this interpretation is problematic for several reasons:

God’s Disgrace – The disgrace referred to in Numbers 14, the “inability of the Lord to bring them into the land,” relates to God, while in Joshua the disgrace is of the people.[2]

No Connection to Circumcision – More significantly, the narrative context in Joshua would seem to dictate that there is a relationship between the removal of the disgrace and the removal of the foreskin; Numbers does not even mention circumcision or foreskins.

How does the “disgrace of Egypt” relate to the circumcision of the Israelites at Gilgal?

Disgrace of Slavery (Kaufmann)

The great Israeli ideologue and historian, Yehezkel Kaufmann (1889-1963), offered a “Zionist” explanation for why the Israelites did not circumcise their sons in the wilderness in his commentary on Joshua on v. 9:

הפסוק מתבאר רק מתוך ההשערה ששיערנו, שישראל נדרו שלא ימולו את בניהם עד שיבואו לארצם. זאת אומרת, שעד אז לא היתה גאולתם שלמה וכאילו נמשכה עוד יציאת מצרים וחרפת שעבודם לא נגולה מעליהם. חרפת מצרים היא איפוא הערלה כזכר לעבדות.

The verse can only be explained based on our suggestions that the Israelites made a vow not to circumcise their sons until they entered their land. Meaning to say that until then their redemption was incomplete, and it was as if the exodus from Egypt was continuing and the disgrace of their bondage was not removed from them. “The disgrace of Egypt” is, therefore, the foreskin as a reminder of slavery.[3]

Kaufmann here invents a vow that has no trace in the Bible and is not implied in this text at all. The fanciful nature of this conjecture is patent.

Disgrace of not Circumcising in the Desert (Blum)

The German Bible scholar Erhard Blum suggests that the disgrace is the very failure of the exodus generation to circumcise their sons in the desert, as they should have.[4] This sinful failure is part and parcel of the decree that the exodus generation must die in the wilderness.

The implication of all of this is that the exodus from Egypt was not truly achieved with the mere arrival in the land. The failure to circumcise had to be corrected before the exodus could truly be achieved. As with Kaufmann’s suggestion, I find this approach to be artificial; there is no indication in any other biblical text that the Israelites of the wilderness period sinned by failing to circumcise.

Disgrace of Being Like Egyptians (Radak)

Radak (R. David Kimchi, ca. 1160-1235) suggested that the circumcision of the Israelites at Gilgal removed the disgraceful foreskin that characterizes the Egyptians. He glosses the words חרפת מצרים with the following comment:

לפי שיצאו האבות ממצרים, והיו הבנים ערלים כמו המצרים, והערלה חרפה כמו שאמר “כי חרפה היא לנו” (בר’ לד, יד).

Since the fathers left Egypt and the sons were uncircumcised like the Egyptians. And the foreskin is a disgrace as it says, “for it is a disgrace for us” (Gen 34:14).

This would have made perfect sense to his readers, but information we now have about ancient Egypt suggest that it is problematic.

Egyptians Circumcised

The ancient Egyptians practiced circumcision. In the words of the 5th century BCE Greek historian Herodotus, they “practice circumcision for the sake of cleanliness, considering it better to be cleanly than comely.”[5]Indeed, the ancient Egyptian “Stela of Uha” (circa 2100 BCE) refers to the circumcision of this official in a communal rite together with an additional one hundred and twenty males.[6]

Even if it circumcision was not considered an absolute requirement for all Egyptians in every period, it is still strange to refer to uncircumcision as a specifically Egyptian trait when so many Egyptians did observe it.[7]

Disgrace According to the Egyptians

Zephaniah 2:8 suggests that this interpretation involves a mistranslation:

צפניה ב:ח שָׁמַעְתִּי חֶרְפַּת מוֹאָב וְגִדּוּפֵי בְּנֵי עַמּוֹן אֲשֶׁר חֵרְפוּ אֶת עַמִּי…

Zeph 2:8 I have heard the reproach of Moab, and the insults of the people of Ammon, with which they have reproached My people…

If חרפת מואב refers to the reproach or insults coming from Moab and directed at the Israelites, it seems reasonable to assume that this is true of חרפת מצרים. This phrase should refer to a disgrace attached to Israel and expressed with derision by the Egyptians and not a disgrace attached to Egypt.

Scorned by Egyptians (Keunen)

Thus, the most compelling interpretation is that God’s dramatic declaration to Joshua in verse 9, “Today I have rolled away from you the disgrace of Egypt,” implies that the Israelites in Egypt were scorned as uncircumcised by their Egyptian superiors.

This reading was suggested long ago by Abraham Keunen (1828-1891),[8] followed by George A. Cooke (1865-1939)[9] and Carl Steuernagel (1869–1958),[10] and has been recently revived by the Italian-Israeli scholar, Alexander Rofé.[11] Following this approach, Joshua introduces circumcision into Israel “today,” at Gilgal, for the first time, since they were not circumcised before this.

Circumcision as Commandment Is Late Priestly

This interpretation, which assumes that Joshua 5:9 introduces circumcision as a rite, is in clear tension with Genesis 17 and similar texts, which speaks of circumcision as a central sign of the covenant with God from the time of Abraham.[12] Nevertheless, that Genesis 17, part of the Priestly source or stratum of the Torah, is likely very late (exilic? Post-exilic?), as is much of P, and does not necessarily reflect pre-exilic practice.

The Absence of the Mitzvah of Circumcision in Biblical Texts

The Decalogue (Exod 20, Deut 5), the Covenant Collection (Exod 21-23), the Cultic Decalogue (Exod 34), the Holiness Collection (Leviticus 17-26), the book of Numbers, and the Deuteronomic Law Collection (Deut 12-26) never mention the “covenant of circumcision.”

In fact, other than the passing note about the circumcision of Isaac in Gen 21:4 (also Priestly), we do not find mention of any biblical character performing or undergoing this supposedly central rite of the covenant of Abraham. Tziporah’s circumcision of her son in Exod 4:24-26, from the non-Priestly source, is performed to save her husband with the use of the blood, and not to bring the child into the covenant of Abraham. Indeed, the story does not use the word “covenant.”

Circumcision as a Cultural Marker

The non-religious and non-covenantal character of circumcision is reflected in the non-Priestly story of the rape of Dinah in Genesis 34, which makes use of the same term “disgrace” (חרפה) as Joshua 5:9:

בראשית לד:יד וַיֹּאמְרוּ אֲלֵיהֶם לֹא נוּכַל לַעֲשׂוֹת הַדָּבָר הַזֶּה לָתֵת אֶת אֲחֹתֵנוּ לְאִישׁ אֲשֶׁר לוֹ עָרְלָה כִּי חֶרְפָּה הִוא לָנוּ.

Gen 34:14 And they said to them, “We cannot do this thing, to give our sister to a man who is uncircumcised, for that is a disgrace among us.

The basis of the brothers’ request, implicitly approved by Jacob, that the people of Shechem undergo circumcision, is that lack of circumcision in a man is considered a disgrace among the Israelites. The text makes no mention of YHWH, Abraham, or covenant. The Shechemites are not asked to recognize Israel’s God, only to, quite literally, remove an ethnic barrier dividing the groups.

Similarly, the derisive reference to the Philistines in a number of relatively early, non-Priestly passages (Judg 14:3; 15:18; 1 Sam 17:26, 36), as being “uncircumcised” (ערלים) make no sense if circumcision was thought of as the unique sign of the covenant between God and Israel. After all, the Philistines weren’t Israelites. Why should any Israelite expect them to be circumcised?!

In short, in pre-Priestly texts that discuss circumcision, it is not a mitzvah from YHWH but a cultural marker. Now that they are on their own land, Joshua introduces circumcision to the Israelites as a sign that they should no longer feel “disgraced” in the eyes of the Egyptians. Instead, like the Egyptians, they too are now circumcised. In this tradition, Joshua—not Abraham—is the father of Israelite circumcision.

The Wilderness Excuse

The verses that precede Josh 5:9, however, argue again this interpretation. They explain why the Israelites had not been circumcised till then (vv. 4-7), insisting that the Israelites who left Egypt were circumcised, and that it was only the next generation, born on the way, that are circumcised by Joshua:

יהושע ה:ה כִּי מֻלִים הָיוּ כָּל הָעָם הַיֹּצְאִים וְכָל הָעָם הַיִּלֹּדִים בַּמִּדְבָּר בַּדֶּרֶךְ בְּצֵאתָם מִמִּצְרַיִם לֹא מָלוּ.

Josh 5:5 Now, whereas all the people who came out of Egypt had been circumcised, none of the people born after the exodus, during the desert wanderings, had been circumcised.

This interpretation is part of an excursus (vv. 4-7[8]) which constitutes a late “correction” of the original text.[13] The redactor cleaned up the problematic claim about the Israelites being uncircumcised until that point by insisting that the Israelites who left Egypt were circumcised and Joshua was only reinstating an earlier practice here.[14]

Joshua’s Idea – Not YHWH’s

A close look at verse 9 supports the assumption that circumcision is understood here as a cultural practice rather than a command from God:

יהושע ה:ט וַיֹּאמֶר יְ-הוָה אֶל יְהוֹשֻׁעַ הַיּוֹם גַּלּוֹתִי אֶת חֶרְפַּת מִצְרַיִם מֵעֲלֵיכֶם וַיִּקְרָא שֵׁם הַמָּקוֹם הַהוּא גִּלְגָּל עַד הַיּוֹם הַזֶּה.

Josh 5:9 Then YHWH to Joshua said: “Today I have removed the disgrace of Egypt from upon you.” He called the name of the place Gilgal until this day.

There are two oddities here:

YHWH Naming the Place –This kind of “place-name etiology” is almost always pronounced by a human character or by the anonymous narrator of the story, not by God.

YHWH Addressing the People – In the verse, YHWH is ostensibly addressing Joshua when, in fact, the words are directed at the people of Israel.

Both these problems can be solved if we assume that the words “YHWH to” were added to the verse (see italics in the quote above), and that, in the original verse, Joshua was speaking. This seems much more natural since it is Joshua who circumcises the people and removes the “disgrace of Egypt” from them. Following this reading, Joshua rather than God named the site Gilgal.

God’s Command to Circumcise

Just as putting the “disgrace of Egypt” speech in God’s mouth is artificial, so too is putting the command to circumcise in God’s mouth. And in fact, a closer look at the opening verse, where God makes this command, shows that it too is redactional:

יהושע ה:ב בָּעֵת הַהִיא אָמַר יְ-הוָה אֶל יְהוֹשֻׁעַ עֲשֵׂה לְךָ חַרְבוֹת צֻרִים וְשׁוּב מֹל אֶת בְּנֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל שֵׁנִית.

Josh 5:2 At that time YHWH told Joshua, “Make flint knives and again circumcise the Israelites a second time.”

According to this verse, Joshua circumcises the Israelites at YHWH’s command, doing so “again… a second time.” This implies that the Israelites were circumcised in the past and flies in the face of the simple reading of v. 9 in which this is the first time Israelites became circumcised.[15]

The phrase “at that time YHWH said” (בעת ההיא אמר ה’) is clearly Deuteronomistic. Note how it closely parallels the style of Deut 10:1, in which Moses says: “at that time, YHWH said to me” (בעת ההיא אמר ה’ אלי). The phrase “at that time” (בעת ההיא) itself is used repeatedly in Deuteronomy and Deuteronomistic literature (Deut 1:9, 16, 18; 2:34; 3:4, 8, 12, 18, 21, 23; 4:14; 5:5; 9:20; 10:1, 8. Cf. Josh 6:26; 11:10, 21; etc.).

Moreover, the idea that the circumcision was part of God’s command—and certainly the references in the MT to this being a second circumcision—fits with the later biblical concept that circumcision is a feature of the Israelite religion, and not merely an ethnic marker. Thus, I would argue that the entire verse is a redactional insertion, together with vv. 5:4-8a and the added words in v. 9.

Joshua’s Idea

Once we remove the supplements and redactions, we are left with a brief account:

יהושע ה:ג וַיַּעַשׂ לוֹ יְהוֹשֻׁעַ חַרְבוֹת צֻרִים וַיָּמָל אֶת בְּנֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל אֶל גִּבְעַת הָעֲרָלוֹת. //ה:ח …וַיֵּשְׁבוּ תַחְתָּם בַּמַּחֲנֶה עַד חֲיוֹתָם. ה:טוַיֹּאמֶר // יְהוֹשֻׁעַ הַיּוֹם גַּלּוֹתִי אֶת חֶרְפַּת מִצְרַיִם מֵעֲלֵיכֶם וַיִּקְרָא שֵׁם הַמָּקוֹם הַהוּא גִּלְגָּל עַד הַיּוֹם הַזֶּה.[16]

Josh 5:3 So Joshua made flint knives and circumcised the Israelites on the Hill of the Foreskins. // Josh 5:8 …and they remained where they were, in the camp, until they recovered. 5:9 Then // Joshua said: “Today I have removed the disgrace of Egypt from upon you.” He called the name of the place Gilgal until this day.

God’s lack of involvement here is supported by the formulation ויעש לו יהושע חרבות צורים, “and Joshua made for himself flint knives,” which implies that the circumcision of the Israelites was Joshua’s initiative.

Adding God into the Picture

The editor converted Joshua’s decision to conduct a mass circumcision of the Israelite men at Gilgal into a divine command to offer it religious significance. The circumcision is performed in compliance with the divine will and is not done merely to appear less “primitive” by the standards of Egyptian culture.

This editorial adjustment removes the troublesome presentation of Joshua as a leader who initiates ceremonial activity on his own, human authority. Joshua does not invent and institute ritual acts, a task that belongs strictly to God.[17] But in the original conception of this brief story, circumcision was not a ritual or a mitzvah but a cultural marker, instituted by Joshua so that the Israelites could now be circumcised like the Egyptians, and no more feel the sting of disgrace.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

March 28, 2018

|

Last Updated

January 29, 2026

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Prof. Rabbi David Frankel is Associate Professor of Bible at the Schechter Institute of Jewish Studies in Jerusalem, where he teaches M.A. and rabbinical students. He did his Ph.D. at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem under the direction of Prof. Moshe Weinfeld, and is the author or The Murmuring Stories of the Priestly School (VTSupp 89) and The Land of Canaan and the Destiny of Israel (Eisenbrauns).

Essays on Related Topics: