Edit article

Edit articleSeries

Reading Biblical Genealogies

Shem, Ham and Japheth. James Tissot, French. c. 1896-1902

Two Types of Genealogical Lists

The Bible makes use of many literary genres, such as narrative, law, and poetry. A frequently overlooked or misunderstood genre is the genealogical list.[1] These lists take two basic forms:

Linear genealogies – These lists trace a lineage through multiple generations most often in descending order, from an ancient eponym (an illustrious ancestor) down to a later offspring who might be the focus of the narrative (Cain: Gen. 4:17-23; Seth: 5). Alternatively, they can start from the hero of the narrative and ascend to a prominent ancestor, e.g. Samuel (I Sam 1:2), Ezra (Ezra 7:1-5) and Mordechai (Esther 2:5).

These lists, which are sometimes embellished with details other than names, present sequential generations providing what social anthropologists call the structural depth of the lineage, or the time line, of that family. The structural depth of such lists is up to ten generations (Gen 5, 11:10-26) expressing in a biblical context an eon (Deut. 23:3, 4).[2]

Segmented genealogy – This form presents a picture of the branches of the clan. The patriarch is named along with his wives or multiple sons providing the spatial (or territorial) depth of the family unit (e.g., Gen 10, 36).

Such a list had a number of functions. Most significantly, knowing who was or was not part of a larger social order could serve as a social contract ensuring the welfare and permitted marital ties of an individual in a tribal society defined by kinship (cf Ruth 4 and the function of the redeemer [goel]).

Literary Messages in Genealogical Lists

The largest concentration of biblical genealogies is found in Genesis (passim) and in 1 Chronicle 1-9, where they serve a literary purpose as well as express an ideological message:

Genealogy in the Service of Davidic Kingship

The book of Chronicles is a history of the Davidic monarchy and its opening genealogies further this historiographic agenda. Chapter 1 of Chronicles includes the genealogies of the peoples of the world found in Genesis and implies that David's kingdom was rooted at the beginning of mankind. Chapters 2-4 deal with Judah,[3] giving this tribe much more space than any other tribe, and include the Davidic genealogy also found in Ruth.The remaining genealogies (chs. 5-8) deal with the other tribes of Israel, including the Levites and the Priests. By using these tribal lists, the Chronicler further ignores the historic Northern kingdom implying that the four-hundred-plus year Davidic monarchy was the sole and legitimate ruler over all Israel.

Delineating Offshoots – Segmented Genealogies in Genesis

Genesis has numerous segmented genealogies, such as “The Table of Nations” (Ch.10),[4] and the lists of the descendants of Nahor (22:20-24), Qeturah (25:1-5) Ishmael (25:12-18) Esau (ch. 36) and Israel (46:8-27). These lists seem to be the earliest inner division of the Book of Genesis, creating logical pauses in the narrative at times of transition. They help in focusing on the evolving narrative by briefly noting the distracting offshoot families in genealogical lists, and ending with the family of interest, i.e., the children of Israel.

The Table of Nations: Humanity as an Extended Family

Genesis 10, known as the "Table of Nations," describes mankind after the Flood; it is a veritable storehouse of ethnographic and geographical information regarding the biblical period. The chapter divides humanity into the descendants of the three sons of Noah: Japheth, Ham and Shem in that order according to their increasing numbers and according to their ethnic closeness to the unmentioned Israel, whose Patriarch Abraham was not yet born.[5]

Every branch includes small units of segmented genealogies. Furthermore, each branch is followed by a summary stating the observable empirical[6] ethnic, geographical and linguistic closeness of that family of nations:

ה מֵאֵלֶּה נִפְרְדוּ אִיֵּי הַגּוֹיִם בְּאַרְצֹתָם אִישׁ לִלְשֹׁנוֹ לְמִשְׁפְּחֹתָם בְּגוֹיֵהֶם.

5 From these the maritime nations branched out. [These are the descendants of Japheth] by their lands -- each with its language -- their clans and their nations.

כ אֵלֶּה בְנֵי-חָם לְמִשְׁפְּחֹתָם לִלְשֹׁנֹתָם בְּאַרְצֹתָם בְּגוֹיֵהֶם.

20 These are the descendants of Ham, according to their clans and languages, by their lands and nations.

לא אֵלֶּה בְנֵי-שֵׁם לְמִשְׁפְּחֹתָם לִלְשֹׁנֹתָם בְּאַרְצֹתָם לְגוֹיֵהֶם.

31 These are the descendants of Shem according to their clans and languages, by their lands, according to their nations.

This chapter expresses the ideal brotherhood of humanity, implying an innate equality and collective responsibility. This ideal is expressed in the use of segmented genealogies creating a world of one big family: the Sons of Noah. It contrasts sharply with the societies of the Ancient Near East, with its pronounced class differences (cf. the Code of Hammurapi). Furthermore, the number of seventy people, as in this Table, is significant in biblical and ANE texts, as this number represents totality (cf. Deut 10,22; 32,8; II Kings 10:1), and here implies the universality of this divine message.[7]

The Twelve Sons of Canaan: An Analysis

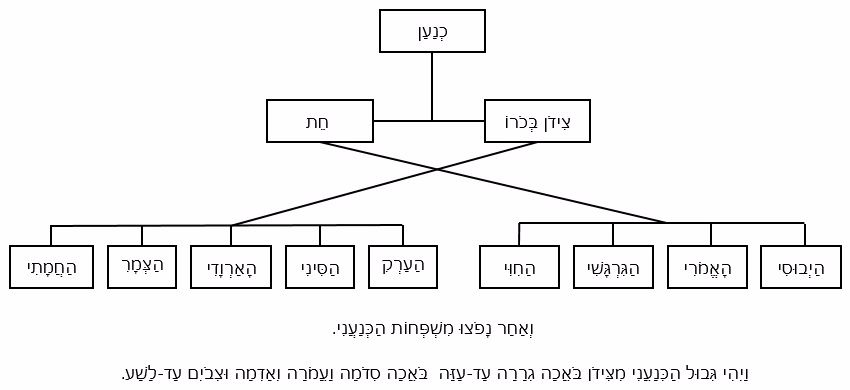

I will use the genealogy of Canaan to illustrate the literary structure and implications. The Sons of Canaan (vss. 15-18) include twelve names.[8]

י:טו וּכְנַעַן יָלַד אֶת צִידֹן בְּכֹרוֹ וְאֶת חֵת.

י:טז וְאֶת הַיְבוּסִי וְאֶת הָאֱמֹרִי וְאֵת הַגִּרְגָּשִׁי. י:יז וְאֶת הַחִוִּי וְאֶת הַעַרְקִי וְאֶת הַסִּינִי. י:יח וְאֶת הָאַרְוָדִי וְאֶת הַצְּמָרִי וְאֶת הַחֲמָתִי וְאַחַר נָפֹצוּ מִשְׁפְּחוֹת הַכְּנַעֲנִי.

10:15 Canaan begot Sidon, his first-born, and Heth; 10:16 and the Jebusites, the Amorites, the Girgashites, 10:17 the Hivites, the Arkites, the Sinites, 10:18 the Arvadites, the Zemarites, and the Hamathites. Afterward the clans of the Canaanites spread out.

In order to come up with twelve Canaanite sons—another typological number implying a full people (see below)—it needed to include different kinds of names.

Ethnic groups – Six of the names are ethnic names, known from the lists of the indigenous Canaanite peoples, that appear either in part or in full some twenty-five times in the Bible. Three of these terms are the externally documented: Canaanites, Amorites and Hittites.[9] The rest are unknown in non-biblical texts: Jebusites, Girgashites and Hivites. The Perizites, who appear in a number of these lists, are not mentioned here.

City-States – The list also includes five Phoenician-Syrian city-states as part of the Canaanite league:

- Sidon along the coast,

- `Arqa (Tel `Arqa, ca.20 kms north east of Tripoli),

- Sin (Shiȃn in the Assyrian sources; in later Jewish documents it is identified with Tripoli in Lebanon),

- Arwad (Ruad, an island port between Tripoli and Latakia),

- Ṣemer (Assyrian Ṣumur, south of Arwad)

- Hamath (Ḫama one of the major cities in middle Syria), situated on the Orontes.

Literary Observations

Grammatical Forms

The names of these “sons” are not presented uniformly.

- The first three—Canaan, Sidon and Heth—are proper names.

- The "descendants" are written as gentilics (i.e., relational adjectives in the nisbe form) with the definite article (the Jebusite, the Amorite), etc. Canaan also appears in this form at the end of the list.

Chiastic Form

The "descendants" are listed in chiastic order. Sidon is the firstborn followed by Heth. Following Heth are the other five Canaanite peoples, related to Heth, and then the five city states, obviously related to Sidon, as they are all Phoenician city-states like Sidon (see chart).

The Significance of Twelve

As we see from the later genealogies of Nahor (Gen 22:20-24), Ishmael (Gen 25:13-15), and of course, Jacob, twelve is a significant number in biblical tradition for classifying large ethnic units, or tribal leagues, in the patriarchal period. In this case of Canaan, however, we find a certain creativity in order to produce the desired number. The list has two anomalies:

- The patriarch here is one of the twelve.

- Five city-states (or feudal kingdoms)[10] have been recast as clan units.

Geographic Notice

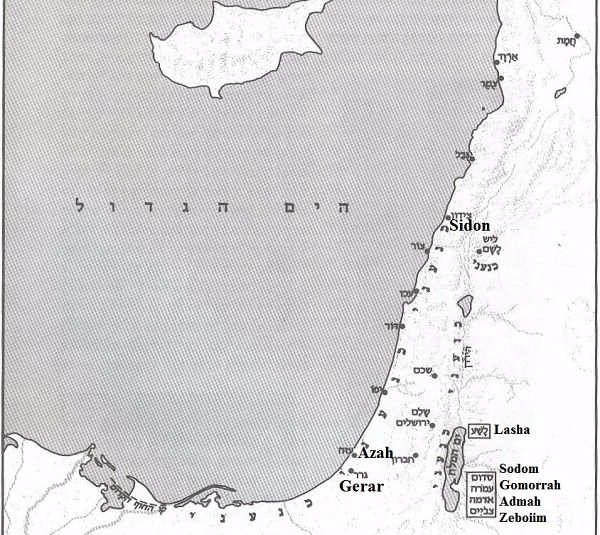

As noted above, the larger branches of the three sons of Noah are defined not only by ethnicity and language affinity, but also by geographic proximity (vss 5, 20, 31). Moreover, emphasizing the integral territorial aspect of tribal identity, sundry geographical notices were appended, e.g., vss. 10-12; 30. Similarly, in vs 19, this genealogy of Canaan is enhanced by a fascinating geographic description of the borders of Canaan (v. 19):

וַיְהִי גְּבוּל הַכְּנַעֲנִי מִצִּידֹן בֹּאֲכָה גְרָרָה עַד עַזָּה, בֹּאֲכָה סְדֹמָה וַעֲמֹרָה וְאַדְמָה וּצְבֹיִם עַד לָשַׁע.

The Canaanite territory extended from Sidon as far as Gerar, near Gaza, and as far as Sodom, Gomorrah, Admah, and Zeboiim, near Lasha.

This description serves both to minimalize Canaanite territory and to introduce places that will appear in later narratives.

Northern Border – Phoenician Cities

Following a three pointed pattern of delineating borders ,which I have identified, i.e., "From X, coming to Y, near Z", the list begins with Sidon, which probably now implies the entire Tyrean kingdom on the Phoenician coast from Acco in the south to Nahr Kalb in the north (Josh. 13:4-6; compare the territory of Asher 19:24-30).[11]

South-Western Border – Philistine Cities

The second point, on the south-western border of Canaan, Gerar (Tel Harur, present day Netivot on Nahal Gerar, i.e. biblical Nahal HaBesor), was defined by the third point Gaza, some 20 kms away.[12] This description of the southern border of Canaan serves another literary purpose by anticipating the stories of Abraham and Isaac going to Gerar and the story of Jacob's funeral cortège from Egypt to Hebron at the end of the book (Gen 50:10-11).[13]

Eastern Border - The Dead Sea and the Five Cities

From the south western corner of the Land, the border goes to the southern edge of the Dead Sea. The description introduces the five cities which are eventually destroyed in the story of Lot and Sodom.[14]

Intricacy of Genealogies

Genealogies are complex and we often need to look very closely at the literary structure in order to appreciate the inherent message of these lists, which reflect early Israelite tribal society and their view of the peoples of the world. Once we do, we can begin to understand the ways in which these lists were used as literary devices as well as to express the grand ideas and values of the Bible.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

November 3, 2016

|

Last Updated

January 30, 2026

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Prof. Aaron Demsky is Professor (emeritus) of Biblical History at The Israel and Golda Koschitsky Department of Jewish History and Contemporary Jewry, Bar Ilan University. He is also the founder and director of The Project for the Study of Jewish Names. Demsky received the Bialik Prize (2014) for his book, Literacy in Ancient Israel.

Essays on Related Topics: