Edit article

Edit articleSeries

The Cherubim: Their Role on the Ark in the Holy of Holies

Decalogue, Lions, and Large Crown 1882, Artist unidentified. Photo by Mark Bealer Folkartmuseum.org

The most intriguing and surprising aspect of the Ark, and possibly the whole Mishkan, are the Cherubs on the Ark’s cover. What are cherubs? The Torah describes them in detail:

שמות כה:יח וְעָשִׂיתָ שְׁנַיִם כְּרֻבִים זָהָב מִקְשָׁה תַּעֲשֶׂה אֹתָם מִשְּׁנֵי קְצוֹת הַכַּפֹּרֶת. כה:יט וַעֲשֵׂה כְּרוּב אֶחָד מִקָּצָה מִזֶּה וּכְרוּב אֶחָד מִקָּצָה מִזֶּה מִן הַכַּפֹּרֶת תַּעֲשׂוּ אֶת הַכְּרֻבִים עַל שְׁנֵי קְצוֹתָיו. כה:כ וְהָיוּ הַכְּרֻבִים פֹּרְשֵׂי כְנָפַיִם לְמַעְלָה סֹכְכִים בְּכַנְפֵיהֶם עַל הַכַּפֹּרֶת וּפְנֵיהֶם אִישׁ אֶל אָחִיו אֶל הַכַּפֹּרֶת יִהְיוּ פְּנֵי הַכְּרֻבִים.

Exod 25:18 Make two cherubim of gold—make them of hammered work—at the two ends of the cover. 25:19 Make one cherub at one end and the other cherub at the other end; of one piece with the cover shall you make the cherubim at its two ends. 25:20 The cherubim shall have their wings spread out above, shielding the cover with their wings. They shall confront each other, the faces of the cherubim being turned toward the cover.

According to this description, cherubs have faces and wings, and God speaks from in between them. What do they represent? Why are they placed on top of the ark?

Traditional Explanations

The Talmud offers several interpretations of the symbolism of the cherubs. One suggestion (b. Chagigah 13; b. Sukkah 5b) connects the face of the cherub with that of a child. This is a common western understanding as well.[1]

מאי כרוב? אמר רבי אבהו: כרביא, שכן בבבל קורין לינוקא רביא. אמר ליה רב פפא לאביי: אלא מעתה, דכתיב פני האחד פני הכרוב ופני השני פני אדם והשלישי פני אריה והרביעי פני נשר – היינו פני כרוב היינו פני אדם! – אפי רברבי ואפי זוטרי.

What is a cherub (keruv)? Rabbi Abahu said: “Like a child (ke-ravya), since in Babylonian Aramaic a child is called ravya.” Rav Pappa asked Abaye: “But, how can you read the verse (Ezek. 10:14), ‘One face was like a cherub and another like a person’ – isn’t a cherub-face and a human-face the same thing?” [Abaye responded:] “One refers to the face of an adult and another to a child.”

According to Rabbi Abahu, a cherub had the face of a child. He bases this on a word play between the Hebrew keruv and the Aramaic ruvya, utilizing the preposition “ke” (=like/as) to make up for the otherwise missing first letter. This suggestion is clearly a midrashic etymology. Ibn Ezra (Exod. 25:18) already noted that the kaf is part of the root of the word. Although suggesting a meaning for the term, Rabbi Abahu does not suggest a meaning for the image. Why should winged children sit atop the Ark?

The Talmud (b. Yoma 74a) discusses what the cherubs represent, rather than what they looked like:

אמר רב קטינא: בשעה שהיו ישראל עולין לרגל מגללין להם את הפרוכת, ומראין להם את הכרובים שהיו מעורים זה בזה, ואומרים להן: ראו חבתכם לפני המקום כחבת זכר ונקבה.

Rav Katina said: “When the Israelites would come to the Temple for the holiday the curtain would be pulled back for them and they would see the cherubs intertwined with each other. [The priests] would say to them: “Behold, the love of you before God is like the love of man and woman.”

Rav Katina explains the symbolism of the cherubs’ wings touching each other. This represents love and should call to mind the love of God to God’s people, Israel. What Rav Katina does not explain is how the love of two creatures who are exactly the same should come to represent God and Israel. This interpretation likely reflects a midrashic connection between the phrase “spreading wings (פרשי כנפים)” used by Exodus to describe the cherubs and the identical phrase Ezekiel 16:8 and Ruth 3:9 for a man spreading his cloak over a woman.[2]

Medieval Commentators

The meforshim (traditional commentators) on Exodus 25:18 offer a number of possible interpretations of the term, as reflected in this survey:

Babies—Rashi endorses the position of the Talmud that they have children’s faces.[3]

A Couple—R. Bahya ben Asher and R. Moshe Alshich, offering a modified version of Rav Katina’s statement, suggest that one was male and one was female.[4] (Rav Katina doesn’t actually say this, but it is possible to read his statement this way.)

Symbol of Procreation—Alshich adds that the meaning of this symbol is related to the mitzvah to procreate.[5]

Frightening Form—Ibn Ezra suggests that the word keruv just means “form” (צורה), and says that the Torah does not tell us here what the form is, other than that they have wings.[6] However, he notes that he explained the meaning in his gloss to Gen. 3:24, which describes cherubs that were placed outside the Garden of Eden to block the path. Ibn Ezra says there that the cherubs were “frightening images” (צורות מפחידות).

Holy Beasts of the Divine Throne—Tying the imagery in with a different biblical account, R. Joseph Bekhor Shor says that ark is the divine throne and the divine throne and the cherubs are the “holy beasts” referenced in Ezekiel.[7] (As will be seen later, he has anticipated modern scholarship here.)

Birds—Rashbam and Chizkuni both suggest that a keruv is a bird (עוף), presumably because they are depicted with wings.

Angels—On the total opposite spectrum, R. Bachya ben Asher says they are angels. This interpretation of cherub associates them with another group of winged angels, the Seraphim mentioned in Isaiah 6. (Most biblical angels do not have wings.) Moreover, R. Bachya suggests that the meaning of the symbolism is to remind the Israelites of the second most important (עיקר) principle in Judaism, the existence of angels; according to him, angels make prophecy possible and without prophecy there can be no Torah. The reason there are two, he suggests, is so that the viewer not mistake the statue for an image of God.[8]

Justice and Mercy—Rav Chaim Paltiel suggests that the two statues represent the two attributes of God, mercy and justice.[9]

Rabbis—R. Jacob ben Asher (Ba’al haTurim) believes they represent two study partners in a beit midrash, having a give and take about Torah.[10]

Modern Scholarship

Modern scholarship approaches the topic of cherubs both by looking at the contextual clues from the biblical stories (similar to what ibn Ezra and Bekhor Shor did) and by looking at the ancient Near Eastern evidence.

Keruvim and Karibu

The name kerub seems to be a loanword from the Akkadian karibu.[11] The word karibu is a noun derived from the Akkadian root karābu, which means “bless.” The karibu are the blessed ones; they were genies or lower level divine beings who function as supplicants, standing before the god and praying on behalf of others. The karibu were generally pictured as colossal bulls.[12] Apparently, the Torah incorporates the Akkadian concept of karibu in the Hebraicized cherub. But was their function there same as their Mesopotamian antecedents? Biblical accounts offer a variety of answers.[13]

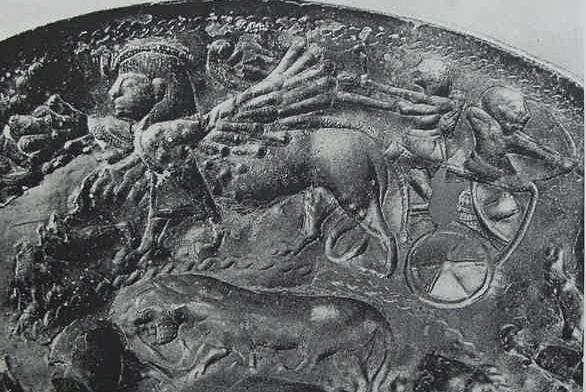

Image 1 – Guards

As noted earlier, Genesis 3:24 suggests that God stations Cherubim outside the garden of Eden to prevent Adam and Eve from trying to re-enter.

He drove the man out, and stationed east of the garden of Eden the cherubim and the fiery ever-turning sword, to guard the way to the tree of life.

From this source, it appears that cherubs are a kind of divine guard. This fits in with the description of the cherubs in Solomon’s Temple as well (1 Kings 6:23-28), which were ten cubits (approximately twenty two feet) high. Unlike the cherubs of the Ark, they were gigantic in size and instead of facing each other they both faced the door. The effect of such a display would be to intimidate people, forcing those who enter the room to be somber and frightening off unauthorized people who might be curious. [14]

Solomon’s daunting cherubs (as well as the cherubs outside the garden of Eden) are highly reminiscent of the Ancient Near Eastern practice of placing giant statues of heavenly beasts, called karibu, apkallu (from Sumerian Abgal), lamassu, sheddu,[15] or alad-lammu outside of palaces.

|

|

Although this is true for Solomon’s cherubs, the cherubs on the Ark, however, do not seem to be guards, since they face each other not the outside, and are small and hardly intimidating.

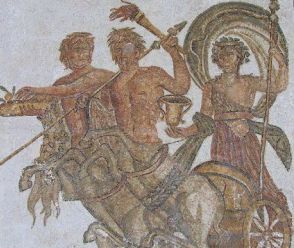

Image 2 – Drawers of the Divine Chariot

A number of biblical texts describe the cherubs as beings that haul God’s chariot. This concept seems related to the idea of the divine chariot, which God is said to ride. Psalms 18:11 and 2 Samuel 22:11 describe God as riding a cherub,[16] but the most famous description of God riding a chariot is in Ezekiel. In truth, the term chariot (מרכבה) doesn’t actually appear in the chapters where the cherubs appear, but since God is described as riding the cherubs, with the cherubs apparently carrying God up into the sky (Ezek. 10:15-20), it seems clear that they are carrying or functioning as God’s chariot. In the opening of the book, Ezekiel describes God appearing to him while riding a divine chariot pulled by creatures with four faces and wings. Ezekiel calls these creatures cherubs (9:3, 10:1, etc.).

The idea of a god or a king riding a chariot pulled by fantastic creatures exists in the Ancient Near East. Phoenician art depicts sphinx driven war chariots, for instance.

(cf. p. 74, fig. 208. Heinz Demisch. Die Sphinx, Geschichte ihrer Darstellung von den Anfangen bis zur Gegenwart. Stuttgart. Verlag Urachhaus Johannes M. Mayer. 1977 (ISBN 3-8738-219-7)

The idea is most developed, and well known, in the ancient Greek and Roman worlds, where many different gods and goddesses are picture with their own chariots. Apollo rides a gryphon, Poseidon a pair of Hippokampi (horse-fish). Helios’ chariot is carried by winged horses, Saturn by serpents, and Dionysius by centaurs. When seen in this context, the imagery of God riding a chariot in the Bible seems in keeping with ancient conceptions and poetic norms.

|

|

|

|

Nevertheless, this image as well does not provide a helpful analogy to the Cherubs function in the Mishkan. Although some biblical texts describe the ark as something brought out for battle, to bring God and God’s wrath down upon the enemy (e.g. Numbers 10:35; 1Sam 4:4-9), these never describe the ark as being pulled by the Cherubs. Additionally, the cherubs are on top of the ark, not underneath it. Furthermore, the ark as described in Mishkan parshiyot is primarily stationary, hidden in the Holy of Holies in the Mishkan. It moves with the Mishkan but otherwise it stays where it is, since God dwells upon the cherubs and the Mishkan is God’s home.

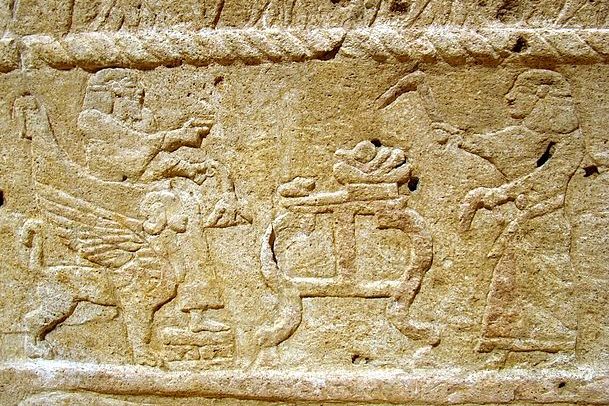

Image 3 – The Divine Throne

In a number of places in Tanach (1 Sam. 4:4, 2 Sam. 6:2, 2 Kings 19:15, Isa. 37:16) we find that God is referred to as “the one who sits upon cherubs (יושב הכרובים). Although this description is not found directly in the Torah, we do read that God is said to dwell in the midst of the Tabernacle, and speak from above cherubs. Accordingly many scholars, understand the cherubs are, likely, part of the divine throne, a kind of platform upon which God will sit or stand and from which God will speak.[17]

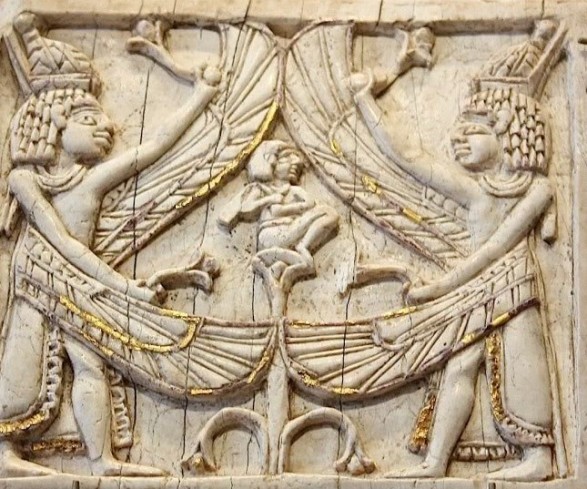

The image of cherubs—making up part of a throne appears in the ancient near eastern iconography. An excellent example of this comes from the carving on the sarcophagus of Ahiram, king of Byblos (a Phoenecian city that is culturally close to Israel) in which Ahiram is depicted sitting upon his throne, designed with a winged gryphon-like creature.

Ahiram’s throne follows Egyptian artistic conventions. In King Tut’s tomb a winged throne was found.

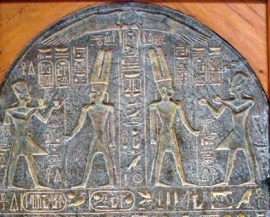

Image 4 – A Buffer for the Divine Podium?

In his excellent essay on the cherubs,[18] Raanan Eichler argues against the idea of the cherubs being a divine throne. He notes a few problems with this suggestion. First, it is generally the ark itself that is emphasized as being synonymous with God’s presence, not the cherubs. Second, the cherubs spread their wings over the ark—this is how they are described, implying that they function as cover for what is below them, not support for what is above them. Third, there is no seat described, and sitting on the edges of the wings would be uncomfortable. Fourth, unlike with ancient Near Eastern thrones, the cherubs are facing each other not forward. This is problematic for the throne theory since the cherubs would be staring at God in a less than modest angle.

Eichler suggests that while the Ark, is the podium or footstool of God, the wings of the cherubs which were standing on two feet rather than all fours, were spread in a protective capacity. The image of wings above a king or even a god serving as protection was a popular image in the ancient Near East, especially in Egypt where the winged sun-disc was a standard iconographic feature.

Eichler further suggests that the wings need not have been above the head of God, but could be envisioned as surrounding God. The benefit of this suggestion is that it dovetails with a motif in Egypt and the Levant, where winged beings spread their wings on either side of a king or deity. Sometimes these beings are facing each other.

This explanation seems to fit biblical and archaeological evidence well.[19]

Conclusion

Tradition has a rich history of interpreting the mythical cherubs in numerous ways. Nevertheless the extensive findings from the Ancient Near East make it clear that the Cherubs historically represented either frightening beasts used as guards, or the equivalent of flying horses drawing chariots; these images fit a number of biblical passages.

In the Mishkan, however, they served either as God’s throne or as buffers surrounding the deity. Accordingly, the Ark of the Covenant was to be the footstool or podium of God. King David says this explicitly in 1 Chronicles 28:2, “Hear me, my brothers, my people! I wanted to build a resting -place for the Ark of the Covenant of the Lord, for the footstool of our God.”[20]

Isaiah 66:1 begins: “ Thus said Yhwh: The heaven is My throne and the earth is My footstool”[21]—the instructions for the construction of the Mishkan may offer a different understanding: “The Cherubs guard My throne and the Ark is My footstool.”

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

February 6, 2014

|

Last Updated

April 14, 2024

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Footnotes

Dr. Rabbi Zev Farber is the Senior Editor of TheTorah.com, and a Research Fellow at the Shalom Hartman Institute's Kogod Center. He holds a Ph.D. from Emory University in Jewish Religious Cultures and Hebrew Bible, an M.A. from Hebrew University in Jewish History (biblical period), as well as ordination (yoreh yoreh) and advanced ordination (yadin yadin) from Yeshivat Chovevei Torah (YCT) Rabbinical School. He is the author of Images of Joshua in the Bible and their Reception (De Gruyter 2016) and editor (with Jacob L. Wright) of Archaeology and History of Eighth Century Judah (SBL 2018).

Essays on Related Topics: