Edit article

Edit articleSeries

An Old Georgian Translation of Esther Incorporates Three Greek Versions

Ahasuerus and his seven eunuchs, (Esther 1:10), Esther Scroll, Zürich, Braginsky Collection, S58. e-codices

A widely accepted, and repeatedly proven axiom in textual criticism is that daughter versions (=translations) of biblical books preserve essential information about the development of these texts. They can also shed light on scribal processes that we theorize took place at earlier stages of composition, for which we have little empirical attestation.

When we study daughter versions in comparison with each other and their older base texts, we learn that at least some scribes and translators rewrote the text to comply with the religious or literary requirements of their time or even just to satisfy their own literary taste. The history of the book of Esther and its translations into Greek, Latin, and Georgian offer an especially compelling example of this phenomenon.

Hebrew and Greek Versions of the Book of Esther

The book of Esther in Hebrew is represented only by the Masoretic text (MT). No fragment of an Esther scroll has ever been uncovered among the Qumran Scrolls, but 4Q550, which contains Aramaic text referring to Esther, seems to know the Masoretic Text.[1]

The Greek editions of the book of Esther are found in three textual forms:

- The Old Greek (OG or Gr.I)—late 2nd/early 1st B.C.E.[2]

- The Alpha Text (AT or Gr.II)—1st C.E.[3]

- The Vetus Latina (VL or La-Gr.III)—a Latin translation of a (mostly) lost Greek original.[4] It is commonly dated to slightly later than the Alpha Text.[5]

None is simply a translation of the Hebrew.[6]

Old Greek Esther: The Oldest Translation

Old Greek Esther is likely the oldest translation of the book of Esther into Greek. Much of it is a fairly accurate translation of the MT, but it also includes six large blocks of text (labelled A–F), currently referred to as “apocryphal additions,” distributed in contextually appropriate parts of the story, which have no basis in the Hebrew original.[7] The author of these six additions (probably the person who translated the Hebrew version into Greek) was dissatisfied with the simple and bland text of the book of Esther and added several elements to the story:

A. Mordechai’s dream—This created a new opening to the book of Esther, taking place in the second year of the king,[8] in which Mordechai has a dream:

Esth OG A:4 …Look! Shouts and confusion! Thunder and earthquake! Chaos upon the earth! A:5 Look! Two great dragons came forward, both ready to fight, and a great noise arose from them! A:6 And at their sound every nation prepared for war, to fight against a nation of righteous people….

The story of Mordechai saving the king’s life from conspirators is next, in a form identical to the story about Bigtan and Teresh in Esther 2:21–23 (more on this later).

B. The First Edict—Once Haman convinces Ahasuerus to allow him to destroy the Jews, the book of Esther (3:12–15) reports that Haman sends out a royal edict. This addition fills in a gap by providing a copy of that edict.

C. Mordechai’s and Esther’s prayers—After Mordechai informs Esther of what Haman is planning to do to the Jews, he urges her to speak to the king. She begins by saying that she wants the Jews to fast for three days (Esth 4:16–17). The Greek text, likely seeing the fasting as part of a larger religious ceremony, first adds a long prayer of Mordechai. Then it adds Esther’s praying, in which she removes her fancy clothes, dons mourning garments, and covers her hair in ashes and dung, calling attention to the heroine’s inner crisis and self-sacrifice.

D. Esther’s preparation—Immediately after the previous addition, the Old Greek describes how Esther changes back into her fancy clothing and prepares to meet the king. It also rewrites the beginning of the scene when she enters, adding drama to Ahasuerus’ reaction to her beauty.

E. The second edict—After Haman is executed, Ahasuerus allows Mordechai and Esther to write a new edict that combats the old one. Again, the Greek fills in the gap by writing the text of the edict.

F. Mordechai’s dream interpreted—Greek Esther ends by connecting to the beginning of the story, when Mordechai thinks back upon his dream and realizes that he and Haman were the two dragons. After this, it reiterates that the 14th and 15th will always be festive observances.[9]

By including the edicts, these changes create the impression of historical truth. By describing prayer scenes, it manifests religious ideas not found in the Hebrew. The added drama between characters, such as the expanded scene of Esther approaching Ahasuerus, as well as the vivid description of Mordechai’s dream, shows human feelings and engages the reader.

The Alpha Text: Improving the Story

While the translator of the Old Greek maintained the core of the book of Esther, merely adding supplemental material, the author of the Greek Alpha Text revised the book more extensively in an attempt to create a more readable, smoothed out version.

Omitting Doublets—The Old Greek version of Esther has several passages retelling the same story or repeating the details.

For example, the Hebrew book of Esther describes how Mordechai overhears two eunuchs planning to kill the king, and warns Esther of this plot, thereby foiling it (Esth 2:21–23). The Old Greek includes this scene in ch. 2 (with some adjustments),[10] but, as noted above, has virtually the same scene earlier on in its addition A, which the OG uses to explain how Mordechai received a position in the court, and why Haman hated him (since he was on the side of the conspirators). Thus, in the Old Greek, the same incident happens twice. The author of the Alpha Text erases the story from chapter 2, leaving only the first incident, in addition A.

Eliminating Redundancy and Verbosity—The Alpha Text also shaves down passages and cuts details that seem superfluous. For example, in chapter 2, when Ahasuerus is looking for a queen to replace Vashti, the MT and OG both have long descriptions of the perfuming of the prospective brides, tell about how Esther pleased Hagai, the eunuch in charge of the maidens before they went to the king, and offer a wordy presentation of how Ahasuerus falls for her. The Alpha Text offers a much briefer presentation, without these details, and just noting that Ahasuerus liked Esther best and made her queen.

Similarly, in chapter 4, when Mordechai tells Esther about Haman’s plan in MT and OG, he tells her about the silver Haman offered, and sends her a copy of the edict. In AT, he merely says “Haman, who is second in command, has spoken to the king against us to put us to death.” The Alpha Text’s version of chapter 9, containing the war and festival details, is also cut drastically short.

Expansions—The Alpha Text also expands the story in certain spots. For instance, when Esther tells Ahasuerus about Haman (ch. 7), the MT and OG have Ahasuerus respond angrily, asking who this wicked person was, and Esther immediately answers it is Haman. The Alpha Text, however, adds:

Esther AT 7:6 When the queen saw that it seemed a grave offense to the king and that he hated evil, she said, “Do not be angry, lord, for it is enough that I have found your conciliation. Enjoy your meal, O King, and tomorrow I will do according to your word.” 7:7 But the king swore that she must tell him who was so arrogant to do this, and with an oath he took it upon himself to do for her whatever she wished…

Elsewhere, the Alpha Text also adds that when Haman was told to bring Mordechai around the city on the king’s horse, he yelled at Mordechai, telling him to remove his sackcloth and put on the king’s finery (AT 6:14–18).

AT also adds a second letter from Mordechai to the Persians, in which he explains:

Esth AT 7(8):36 Haman sent to you letters containing thus, ‘Hasten quickly to send the disobedient nation of the Judeans to me for destruction.’ 7(8):37 But I, Mordechai, inform you that the one who did this has been hung at the gates of Susa, and his household has been dispatched. 7(8):38 For this one wished to kill us on the thirteenth of the month that is Adar.

These and other changes were added for rhetorical effect and to smooth out details in the narrative.

The Vetus Latina: An Alternative Improvement

The same principle of working on the text that we found in the Alpha Text can be seen in the third Greek version, which is extant only in the Vetus Latina (Old Latin)[11] translation.[12]

Omitting Doublets—Like the author of the Alpha Text, the author of the Vetus Latina text was bothered by the doubling of the story about Mordechai overhearing a plot against the king. In this case, however, the VL omitted the story from Addition A, and retained this episode only in its original spot, in chapter 2.

Eliminating Material—As noted, the Alpha text shaves down chapter nine’s repetitive account of the war between the Jews and Haman’s followers. The Latin text goes even further and eliminates the account of the war altogether, including the killing of Haman’s sons. It moves instead straight from the enemies of the Jews being afraid in the opening verses of the chapter to Mordechai writing down the events in a book and establishing the festival (9:21–23).

Jean-Claude Haelewyck of the Catholic University of Louvain, the editor of the critical edition of VL Esther, therefore calls the Latin version “a peaceful text.” In his opinion, the editor deliberately removed “vindictive and vengeful side" from the book as the translation should have been read in the diaspora and “such an accent could only have provoked the Gentiles’ animosity.”[13]

Expansions—In the OG Esther and the Alpha Text, Esther says in prayer that she knows many stories from the books of the Fathers that prove that God heard the prayers of his people and saved his nation. The VL text expands on this with specifics:

Esther VL C:16 [§114] I have heard in my ancestral books, LORD, that you handed over to Abraham nine kings, with 318 men. I have heard in my ancestral books, LORD, that you delivered Jonah from the belly of the whale. I have heard in my ancestral books, LORD, that you delivered Hananiah, Azariah, Mishal from the furnace of fire….[14]

This rhetorical style connects Esther’s plight with Jewish history and increases the emotional impact of the narrative.

The Latin text also adds an original section of its own into the story. The book of Esther describes how, after the distribution of the king’s edict, “the city of Susa was thrown into confusion” (3:15) and that Jews found themselves in mourning (4:3). A little later, after Mordechai’s prayer, the Old Greek Esther says that “all Israel cried out from their strength because their death was before their eyes” (C:11).[15] The Latin text expands on this, adding alongside the prayers of Mordechai and Esther, another prayer of the Jewish people, about five verses long; scholars call this “addition H.”[16]

The Old Georgian Translations of the Book

When Christian scribes in Georgia[17]—the European country, not the American state—came to translate the book of Esther into Georgian for their Bibles, they had (at least) three options to choose from.[18] Three Georgian translations of Esther are extant, reflecting different choices made by different translators.[19] Two of these translators chose a simple path: The Bakari version,[20] a later medieval translation referred to as Georgian 3 (GeIII), uses the Old Greek,[21] while the Oshki version,[22] an early translation referred to as Georgian 1 (GeI), uses the Alpha Text.[23]

In contrast, the other early Georgian translation, referred to as Georgian 2 (GeII),[24] combines all three textual forms currently known in the Greek tradition. Working with the Old Greek as a base-text, the author (probably a Greek scribe but possibly the the Georgian translator) interwove material both from the Alpha Text and the Greek Vorlage (=original) of the Vetus Latina, and even included additional textual material, as the following examples illustrate.

A. Fourteen Eunuchs

At his second party, Ahasuerus gets drunk and sends seven eunuchs to bring Vashti so he can show off her beauty:

אסתר א:י בַּיּוֹם הַשְּׁבִיעִי כְּטוֹב לֵב הַמֶּלֶךְ בַּיָּיִן אָמַר לִמְהוּמָן בִּזְּתָא חַרְבוֹנָא בִּגְתָא וַאֲבַגְתָא זֵתַר וְכַרְכַּס שִׁבְעַת הַסָּרִיסִים הַמְשָׁרְתִים אֶת פְּנֵי הַמֶּלֶךְ אֲחַשְׁוֵרוֹשׁ. א:יא לְהָבִיא אֶת וַשְׁתִּי הַמַּלְכָּה לִפְנֵי הַמֶּלֶךְ בְּכֶתֶר מַלְכוּת...

Esth 1:10 On the seventh day, when the king was merry with wine, he commanded Mehuman, Biztha, Harbona, Bigtha and Abagtha, Zethar and Carkas, the seven eunuchs who attended him, 1:11 to bring Queen Vashti before the king wearing the royal crown…

These unusual names posed difficulties for later translators. Unsurprisingly, the Alpha Text skips the names altogether, but the Old Greek as well as the Vetus Latina both include names. Each list, however, is totally different:

|

Esth OG 1:10 Now on the seventh day, when he was feeling merry, the king told Haman and Bazan and Tharra and Boraze and Zatholtha and Abataza and Tharaba, the seven eunuchs who attended King Artaxerxes, |

Esth VL §20 {1:10} Now, on the seventh day, the king—being tipsy—ordered Maosma and Narbona and Nabattha and Zatai and Achedes and Thares and Tarecta, the seven eunuchs who ministered in the sight of king Artaxerxes, |

To make sure no eunuch was left behind, the Georgian text combined these lists, and includes fourteen names:

And on the seventh day, when he was feeling merry after the feast the king…[25] told to his slaves: Aman and Malan and Thara and Boraze and Totha and Abataza and Tharaba and Gamoma and Arbo and Agab and Zatha, and Chaid and Thari and Therachath, the seven eunuchs who served King;

Notably, while the translator included all fourteen names, GeII still lists them as the traditional “seven eunuchs” of Ahasuerus, creating an incoherent text.

|

|

|

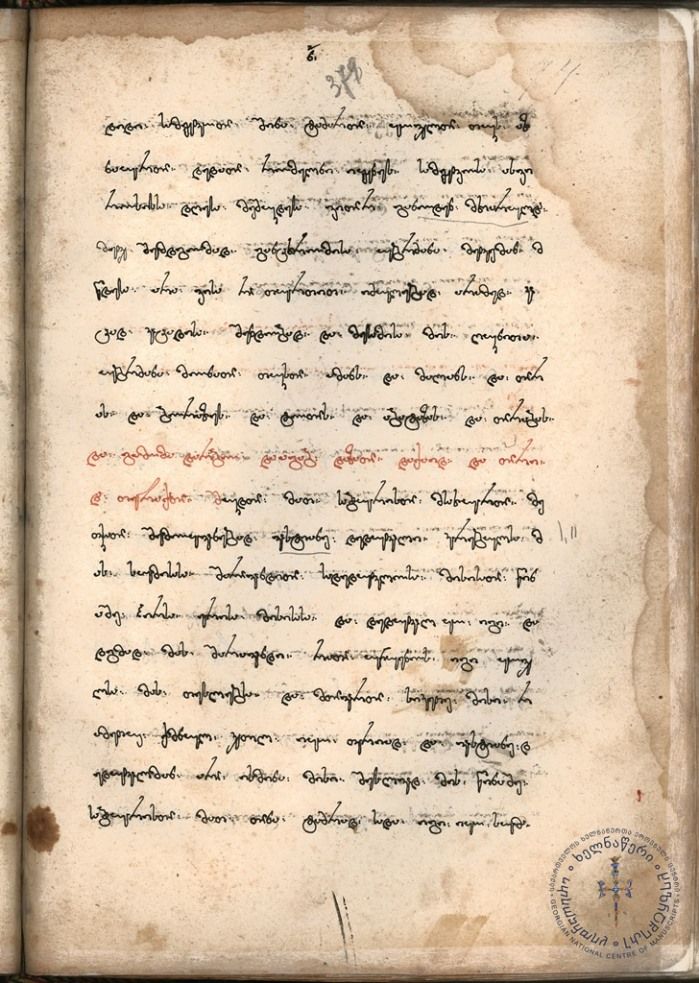

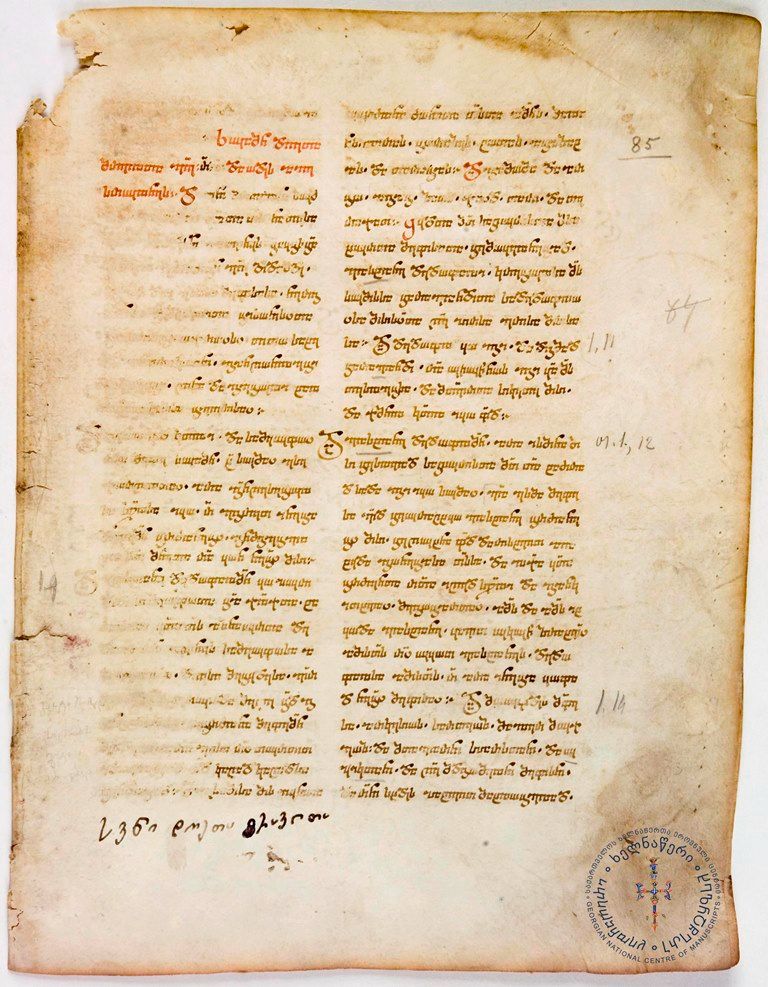

| a. NCM A 646-379r | b. NCM H 885-31r | c. A 570-85r |

|

Three manuscripts of GeII on the page featuring the list of 14 eunuchs (1:10). Courtesy of K. Kekelidze Georgian National Centre of Manuscripts. In NCM A 646, the second set of eunuchs is written in red ink. |

||

B. Haman Casts Lots Twice

An awkward feature of the book of Esther is that once Haman becomes angry with Mordechai, he casts lots to decide when to destroy the Jews, before he ever speaks with Ahasuerus. This section, in italics below, interrupts the flow of the text:

אסתר ג:ו ...וַיְבַקֵּשׁ הָמָן לְהַשְׁמִיד אֶת כָּל הַיְּהוּדִים אֲשֶׁר בְּכָל מַלְכוּת אֲחַשְׁוֵרוֹשׁ עַם מָרְדֳּכָי. ג:ז בַּחֹדֶשׁ הָרִאשׁוֹן הוּא חֹדֶשׁ נִיסָן בִּשְׁנַת שְׁתֵּים עֶשְׂרֵה לַמֶּלֶךְ אֲחַשְׁוֵרוֹשׁ הִפִּיל פּוּר הוּא הַגּוֹרָל לִפְנֵי הָמָן מִיּוֹם לְיוֹם וּמֵחֹדֶשׁ לְחֹדֶשׁ שְׁנֵים עָשָׂר הוּא חֹדֶשׁ אֲדָר. ג:ח וַיֹּאמֶר הָמָן לַמֶּלֶךְ אֲחַשְׁוֵרוֹשׁ יֶשְׁנוֹ עַם אֶחָד...

Esth 3:6 …Haman plotted to destroy all the Jews, the people of Mordechai, throughout the whole kingdom of Ahasuerus. 3:7 In the first month, which is the month of Nisan, in the twelfth year of King Ahasuerus, they cast Pur—which means “the lot”—before Haman for the day and for the month, and the lot fell on the thirteenth day of the twelfth month, which is the month of Adar. 3:8 Then Haman said to King Ahasuerus, “There is a certain people…”[26]

Both the Old Greek and the Vetus Latina maintain this timeline, but the Alpha Text, in keeping with its preference for simplicity, adjusts the timeline by moving Haman’s casting of lots to after the conversation with Ahasuerus, a more logical spot. GeII—again probably a Greek scribe though possibly the Georgian translator—faced with these conflicting timelines, adopts both, and has Haman casting lots twice. Haman first casts lots before he speaks with Ahasuerus, in line with the Old Greek and Vetus Latina:

Esth GeII 3:7 He made a decision in the twelfth year of Ahasuerus' reign and cast lots day-by-day and month-by-month so that the race of Mordechai and Israel might perish on one day. The lot fell on the fourteenth of the month Adar that is Igrika.

Then after Haman and Ahasuerus converse, he casts lots again, following the Alpha Text:

Esth GeII 3:7* And Haman come out from the King’s and went to his gods to learn the day of their death and cast lots for the thirteenth day of the month to murder all the Judeans, from male to female, and to take their young children as plunder.

The text makes no attempt to explain why Haman should cast lots twice. The decision to include both has no narrative logic, it merely expresses the GeII’s desire to include all the incidents in the various available Esther texts.

C. Creating Two Royal Edicts: A Harmonistic Revision

The book of Esther describes how the royal edict against the Jews was sent across the land:

אסתר ג:יד פַּתְשֶׁגֶן הַכְּתָב לְהִנָּתֵן דָּת בְּכָל מְדִינָה וּמְדִינָה גָּלוּי לְכָל הָעַמִּים לִהְיוֹת עֲתִדִים לַיּוֹם הַזֶּה. ג:טו הָרָצִים יָצְאוּ דְחוּפִים בִּדְבַר הַמֶּלֶךְ וְהַדָּת נִתְּנָה בְּשׁוּשַׁן הַבִּירָה...

Esth 3:14 A copy of the document was to be issued as a decree in every province by proclamation, calling on all the peoples to be ready for that day. 3:15 The couriers went quickly by order of the king, and the decree was issued in the citadel of Shushan (=Susa)…

In other words, the same proclamation was to be sent everywhere, including Shushan. The Old Greek translates more or less along these lines:

Esth OG 3:14 Copies of the letters were posted in every land, and it was ordered all the nations to be ready for this day. 3:15 The matter proceeded quickly even to Susa… (NETS).

This description apparently bothered the other ancient translators. If the edict went all over the empire, obviously it appeared in Susa, which is the capital from which it originated. While this is not really a narrative problem—the story takes place in Susa, so we are just witnessing the transition from a wide lens to a more focused one—the other two Greek translations soften the (perceived) problem, each in its own way:

As was its want, the Alpha Text pares the description down to what is necessary for the narrative, and merely writes:

Esth AT 3:19 {15} And in Susa this decree was posted.[27]

The Georgian text kept the Old Greek rendering intact, but also wanted to include the Alpha Text formulation. To do so, GeII reinterpreted the Alpha Text passage as a reference to a different edict. Instead of writing a second edict, GeII takes the edict contained in Addition B, and splits it in half, adds a new introduction to the latter part (vv. 6b–7), which, in GeII, is a special edict directed at Shushan:

Esth GeII B:6 …In the city of Susa, where the king was, the copy of this letter was also spread: “On the fourteenth day of Adar, which is Igrika, of this present year eliminate all the Judeans and take their children as plunder…”

While the solution is creative, and includes new wording unique to this version, the motivation seems to be conservative: the author wished to include as much of the source texts as could be retained, to make this version of the Book of Esther as complete as possible.[28]

D. Mordechai and Esther Both Plead

In the Hebrew book, after Ahasuerus executes Haman, he gives Haman’s household over to Esther, who then gives it to Mordechai. Esther then once again begs the king for help:

אסתר ח:ג וַתּוֹסֶף אֶסְתֵּר וַתְּדַבֵּר לִפְנֵי הַמֶּלֶךְ וַתִּפֹּל לִפְנֵי רַגְלָיו וַתֵּבְךְּ וַתִּתְחַנֶּן לוֹ לְהַעֲבִיר אֶת רָעַת הָמָן הָאֲגָגִי וְאֵת מַחֲשַׁבְתּוֹ אֲשֶׁר חָשַׁב עַל הַיְּהוּדִים.

Esth 8:3 Then Esther spoke again to the king; she fell at his feet, weeping and pleading with him to avert the evil design of Haman the Agagite and the plot that he had devised against the Jews.

This is also what we find in the Old Greek and Vetus Latina translations.

Esth OG 8:3 Then she spoke again to the king, and she fell before his feet and pleaded that he revoke the evil of Haman and what he had done to the Judeans.[29]

In the Alpha Text, however, after commanding that Haman be executed, Ahasuerus turns to Esther and expresses astonishment that Haman would dare try to execute Mordechai, who had saved the king’s life. Then he calls Mordechai before him:

Esth AT 7:15 So the king called Mordechai and granted him all that belonged to Haman. 7:16 And he said to him, “What do you want? I will do it for you.” And Mordechai said, “That you revoke Haman's letter.” 7:17 So the king entrusted to him the affairs of the kingdom.

To solve the problem of who it was that asks the King to revoke the decree, GeII has both Esther and Mordechai pleading together:

Esth GeII 8:3 Esther and Mordechai spoke again to the king, and they fell before his feet and they pleaded that he revoke the evil of Haman and what he had done to the Judeans.

This allows GeII to include elements of both versions. In doing so, he introduces the idea of Mordechai bowing and pleading, something that does not appear in any of the other versions. Notably, this may contradict Mordechai’s reluctance to bow to Haman (Esth 3:2),[30] and certainly contradicts Mordechai’s prayer in Addition C, where he says “I will not bow to anyone but you, my LORD” (Esth OG C:7). Whoever added Mordechai into the scene did not take into account that it was against Mordechai’s credo.

A Conservative yet Creative Compiler

In sum, GeII (or more likely, its Vorlage,) while based on the Old Greek, incorporates all existing forms of the book of Esther (and even some that are lost). In some cases, the result is a coherent readable text, while in others, this completeness creates narrative confusion or contradictions.

Like the compiler of the Pentateuch or the Diatessaron,[31] the editor of GeII had extensive material to compile and his goal was to adopt as much as possible. In this process, the editor is not always capable of maintaining a smooth text, because it is more important for him to document and preserve as much textual data as possible; he is thus willing to sacrifice coherence for this greater purpose. At the same time, this method allowed the editor some room for creativity, and thus GeII has details and features unparalleled in the other textual versions.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

March 4, 2023

|

Last Updated

February 5, 2026

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Dr. Natia Mirotadze is a post-doctoral researcher at the department of Biblical Studies and Church History of Salzburg university and a researcher at the department of Codicology and Textual studies of the Korneli Kekelidze Georgian National Centre of Manuscripts. She holds an M.A. in Old Georgian Philology and a Ph.D. in Old Georgian Biblical Studies, both from the Ivane Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University. Her dissertation was on The Pericopes of I Kingdoms in the Georgian Lectionaries: Their Relation to the Georgian and Greek Sources, and she is the co-editor of Old Georgian versions of the Book of Esther (2014); Proclus Diadochus – Platonic Philosopher, Elements of Theology (Georgian Version) (2016); Georgian Palimpsests at the National Centre of Manuscripts: Catalogue, Texts, Album (2017); Georgian Manuscripts Copied Abroad in Libraries and Museums of Georgia (2018); and From Scribal Error to Rewriting: How (Sacred) Texts May and May Not Be Changed (2020). Her research interests cover textual criticism, biblical studies, manuscript studies, codicology, Georgian paleography, and Old Georgian language and literature.

Essays on Related Topics: