Edit article

Edit articleSeries

Did the Discovery of Hammurabi’s Laws Undermine the Torah?

Torah scroll and Stele of Hammurabi. Wikimedia

In December 1901, French archaeologists excavating the ancient site of Susa in southern Iran came across a remarkable object: the fragment of a black diorite stone covered with text in small cuneiform letters in the Akkadian (Babylonian) language.[1] Two months later, in January 1902, two more fragments were found, completing one of the most important archaeological artefacts from the ancient Near East: the stele of Hammurabi, the Old Babylonian king from the 18th century B.C.E. This stele is now on display in the Louvre in Paris.

Vincent Scheil, a French Assyriologist and member of the Susa expedition, immediately recognized the importance of the find and began translating the cuneiform text at a breath-taking pace. His French translation was published in summer 1902, only a few months after the object was excavated.[2] Translations into other modern languages followed apace, including popular versions for what was commonly called the educated public.[3] Inscribed on the stele are over 100 laws and regulations, which is why the text is known as the Laws of Hammurabi or Codex Hammurabi.[4]

A Religiously Optimistic First Approach

Initially, Christian and Jewish scholars who believed in the authenticity of the Hebrew Bible and the historical truth of its narratives welcomed the discovery of the stele, as they did with many other discoveries of ancient Near Eastern monuments and texts. They saw these finds as corroborating the authenticity and historical truth of the biblical narratives.[5]

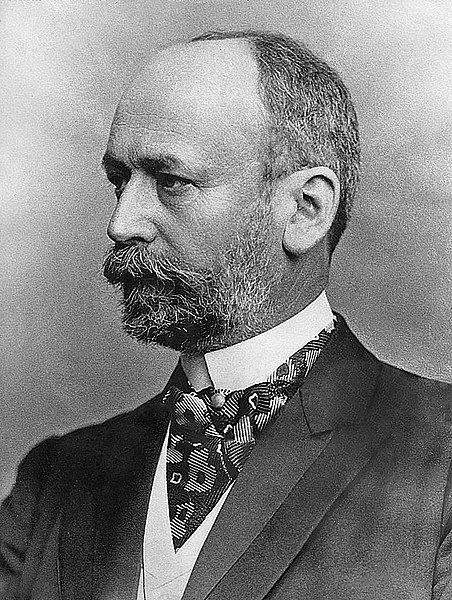

The new knowledge about the ancient past was of particular importance to conservative Christians who used it as a weapon against their major enemy in biblical studies: philological or “higher” criticism, as represented by liberal scholars such as Julius Wellhausen. For Eduard König, for instance, a fierce opponent of higher criticism, the Hammurabi stele proved not only that a complex law system had existed in the very early periods of Near Eastern history but also that the ancient Hebrews had not been primitive nomads before settling in Canaan.[6]

Orthodox Jewish scholars such as Seligmann Meyer similarly expressed the hope that the Hammurabi Stele would contribute to a better understanding of Jewish antiquity and confirm the historical truth of the Hebrew Bible.[7] This positive attitude to ancient Near Eastern texts, however, soon shifted.

The Babel und Bibel Controversy

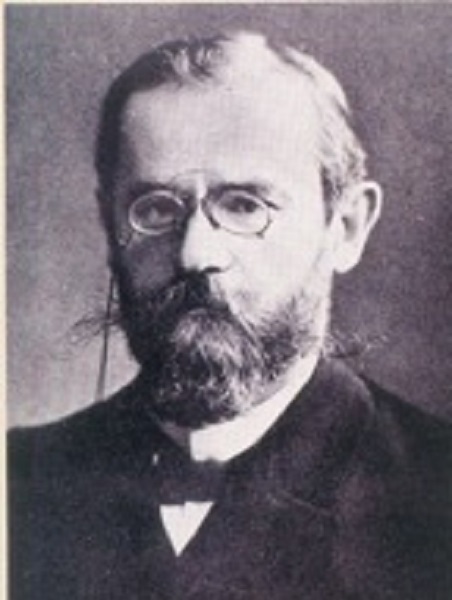

The discovery of the Hammurabi Stele fit well into the argument made by the prominent German Assyriologist Friedrich Delitzsch in his series of lectures known as Babel und Bible (Babylon and Bible).[8] Delitzsch offered a detailed list of parallels between biblical and cuneiform sources, arguing for the dependence of the biblical material on the latter.[9]

The equivocal character of the ancient Near Eastern material had already become evident earlier, in the context of British Assyriologist George Smith’s discovery of the so-called Flood Tablet in 1872.[10] On one hand, the similarities between the flood stories in the Mesopotamian Epic and the Bible could be used as textual evidence of the veracity of the biblical narrative; if multiple ancient texts spoke about a giant flood, does that not increase the likelihood that there was one? On the other hand, if other ancient Mesopotamian texts told a flood story similar to that of Noah and the ark, does that not imply that the biblical authors were merely adapting an older Babylonian (or Sumerian) myth to an Israelite (or Judahite) context, and that the Torah is not a divinely-given text?[11]

The antiquity of the Hammurabi Stele was similarly problematic, since it could be seen as calling into question the originality of biblical law.[12] From the beginning, it was understood that the Laws of Hammurabi were much older than the Mosaic law. The commonly accepted chronology at the time placed the era of Hammurabi in the early third millennium B.C.E., whereas Moses was dated to mid-second millennium.[13] Thus, Delitzsch’s question as to whether the Israelite laws had been influenced or even shaped by the much older Babylonian law were meant as rhetorical, since it had to be that way.[14]

A similar kind of triumphalism is detectable in the subtitle of the first German translation of the stele by the Assyriologist Hugo Winckler: “The World’s Oldest Statute Book” (Gesetzbuch). Before 1902, this epithet would have been reserved for the Mosaic law.

Antisemitic?

To some extent, Winckler’s and Delitzsch’s triumphalist tone, and their desire to present Mosaic law as an inferior and derivative product, was motivated by their anti-clericalism and not least by their antisemitism. In this period, all debates about the role of the Hebrew Bible and the contribution of the ancient Israelites to the history of civilization affected their supposed heirs, the modern Jews, and was inevitably tied to the so-called Jewish question.[15]

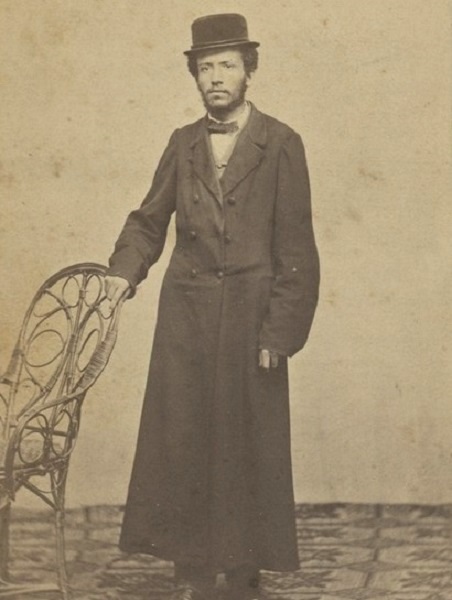

But it would be a mistake to reduce the scholarly enthusiasm for Hammurabi solely to antisemitic biases. Some of those scholars took up Hammurabi’s part, so to speak, were themselves Jews or of Jewish background, like the Assyriologist Felix Peiser or the historian Friedrich Lehmann-Haupt, while most of the Christian defenders of Moses were not by any means defenders of the Jews.

Instead, the main issue was that these scholars rejected the heavily Christocentric perspective of European scholarship. The similarities between the two law collections were grist to the mill for these scholars, who were eager to bring the ancient Near East into sharper focus as a counterbalance.

The Religious Necessity of Disentangling Moses from Hammurabi

In turn, thwarting the argument that Moses was a mere copyist adorned with laurels that rightly belonged to Hammurabi, was of great importance to the Christian and Jewish defenders of the Bible. They had to demonstrate that the biblical laws did not depend on those of Hammurabi.

The most influential contribution to this line of argument came in the form of the thorough investigation published by the Austrian-Jewish orientalist David Heinrich von Müller.[16] To facilitate comparison, he created tables juxtaposing the provisions contained in different ancient law codes: the codes of Hammurabi, Moses, and the Twelve Tables which were said to be the oldest Roman legislation.

While he emphasized the close connection and the strong parallels between the two codes, he argued that the Laws of Hammurabi could not have been the source for Moses since the formulations and arrangement of the rules in biblical law were more “original.”[17]

Müller concluded that there had been no direct historical links between the two codes, but that both stemmed from a common source—an original law laid down in an earlier time—so that Moses did no longer appear as a mere copyist.[18] Furthermore, he argued that biblical version was closer to the supposed original law and thus more authentic. What appears to have been an awkward compromise became widely accepted by Christian as well as Jewish scholars of the time.[19]

Babylonian Modernity and Secularism

A second argument put forth by Delitzsch in his Babel und Bibel lectures was even more challenging to traditional thinking: Delitzsch claimed that the Laws of Hammurabi were actually more developed or modern than those of the Bible. This claim became the central charge, so to speak, of scholars about whom Suzanne Marchand has coined the happy phrase “furor Orientalists.”[20] It was not a distinctive school of thought but a loose group of scholars who tried to decentralize Christianity and classical antiquity in history in favor of the ancient Near East. Following the so-called pan-Babylonism, for instance, almost all cultural achievements stemmed from ancient Babylonia.

The argument that the Babylonian legal code was more advanced fit very well into the general “Babelmania” of the day. The German excavation of the ancient site of Babylon at the turn of the century confirmed the image of Babylonia as a highly developed civilization, more modern than ancient Israel. As a consequence, anything regarded as Babylonian came to be seen as symbolizing modernity, and references to ancient Mesopotamia abounded in the context of modern culture, art and architecture.[21]

In this sense, Babylomania had much in common with European Egyptomania of the same era, but Egypt and Babylon did not symbolize the same: Whereas Egypt, as Hegel put it, was a “symbol of the sublime” associated with eternity and secret traditions,[22] Babylon represented human civilization with all its effects and consequences—the subdue of nature, the rise of big cities and commerce, the building of Empires and the colonization of others (things that were not deemed negative, but eminently positive by these scholars).

A Secular Hammurabi?

The main aspect of the assumed modernity of Hammurabi’s reign was its supposed non-religious or even secular character—always in contrast to Mosaic law, as Winckler underlined:

His laws are responses to practical needs […] not to spiritual or theological speculations as with the biblical legislation.[23]

The historian of law Josef Kohler and the Assyriologist Felix Peiser, editors of the most thorough (German) edition of the Code, published in 1904, went even further, claiming that the modern distinction between morality and law could be traced back to ancient Babylonia. In their view, its secular or profane character is what distinguished the Laws of Hammurabi from, and rendered it superior to, the theocratic systems of law of all other Oriental civilizations.[24] Their rejection of “theocracy” reflected the ideological formation of German secularism, and clearly mirrored the position of these scholars in the debate on the meaning and the status of religion in contemporary German society.[25]

Which historical parallels were drawn by whom was quite telling in this respect: whereas French scholars favored comparisons between Hammurabi and Napoleon—both “fathers” of famous law codes[26]—the Germans compared Hammurabi to Charles the Great or the much-admired Prussian kings of the eighteenth century, Frederick William I and Frederick II.[27] Even the German Emperor (Kaiser William II) himself admired Hammurabi and devoted a small book on ancient Mesopotamia when he was in exile.[28]

Babylonian and Biblical Ethics

Although most scholars of the time accepted the image of Hammurabi as a modern and enlightened ruler, the preference that the modernist furor Orientalists granted to the Babylonian king at the expense of Moses was contested by many, including theologians and biblical scholars, who attempted to rescue Mosaic law from the implication that it was backwards in comparison with Hammurabi’s.

The main line of argument was again developed by Müller and focused on the ethical superiority of the Mosaic law. Compared to the biblical law the Babylonian law appeared much harsher: Capital punishment is omnipresent in the code of Hammurabi and obligatory even for minor delicts like theft; and the treatment of slaves under biblical law was far laxer than that under the Code of Hammurabi.[29] Recalling this, Müller argued that Moses was responsible for introducing key elements that hadn’t existed in law until then: “Wisdom, mercy and ethical greatness.”[30]

In a long review of Müller’s book, Rabbi David Feuchtwang, of Vienna, went beyond Müller, emphasizing the “moral chasm” between the two codes. On these grounds, he strongly denied any continuity:

No direct path would have led from here to the flowering of all laws, to the world-transcending Ten Commandments.[31]

There was no principal difference between Christian and Jewish religious scholars in this respect: neither group had any difficulty accepting the cultural superiority of the Babylonians in general. But in contrast to the modernist and secularist perspective of scholars like Delitzsch, Kohler, Winckler, Peiser or Lehmann-Haupt, scholars of both religions claimed an ethical or moral superiority for the Israelites.

In other words, whereas modernists and secularists regarded the unity of or non-distinction between law and morality in Mosaic law as a sign of its backwardness and inferiority, religious scholars pointed to that same lack of distinction as proof of its progressivity and superiority. As the Swiss theologian and Bible scholar Samuel Oettli emphasized:

There is no question but that the civil life reflected in the Codex Hammurabi is far more developed than that reflected in the Covenant Code; but it is equally beyond doubt that a different, a truly humane spirit struggles forth in this [latter] and in the later law collections of the Torah, one whose source lies in the religious faith of Israel, which is incomparably purer and more fruitful ethically.’[32]

Looking Back a Century Later

From our perspective nowadays, the attempt to compare two ancient societies and their laws is strange and anachronistic. We do not generally judge ancient societies by their level of modernity, nor do we look at ancient law codes as the normative basis of our own. In contemporary society, Hammurabi has completely disappeared from today’s debates about the foundations of law, and Mosaic law is not far behind. Nevertheless, religion remains an important feature of contemporary society, and the question of how Mosaic law developed and what its relationship may have been to other law collections of the period continues to be debated.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

February 16, 2021

|

Last Updated

March 22, 2025

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Dr. Felix Wiedemann is a Privatdozent (Lecturer) and researcher at the Department of History at Freie Universität Berlin. He holds a Ph.D. (2006) and Habilitation (2018) both from Freie Universität Berlin. Wiedermann is the author of Am Anfang war Migration [In the Beginning There Was Migration] (2020) and Rassenmutter und Rebellin [Race Mother and Rebel] (2007). His research interests include the history of science and historiography, theory of history, migration-history, European orientalism(s), history of modern anti-Semitism and racism, right-wing extremism, and new religious movements.

Essays on Related Topics: