Edit article

Edit articleSeries

Part 10

Editions and Translations of MT

Although the vast majority of Bible editions present the consonantal text of MT with the Masoretic pointing, they actually differ from one another in many small details.[1] Such differences occur either because these editions are based on different medieval Masoretic manuscripts or because modern editors have differing conceptions for how to represent these manuscripts.[2]

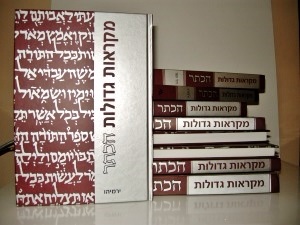

In modern times critical Orthodox scholars realized that it is difficult to speak about a single Masoretic Text, since the medieval text of MT is known in many almost—but not quite—identical manuscripts. These small complications were accepted as reality by Menahem Cohen, a specialist in masorah from Bar-Ilan University, and editor of Bar Ilan’s critical Mikraot Gedolot (Rabbinic Bible) series, HaKeter.[3]

Because the medieval texts differ very slightly among one another, scholars use one of the ancient MT codices as a yardstick for comparison. Many scholars prefer to use the oldest complete manuscript of MT, namely the Leningrad Codex. Even scholars who prefer to work with the Aleppo codex must turn to codex L for work on almost the entire Pentateuch.

Critical Editions

MT is also in the center of scholarly critical editions (sometimes called scientific editions), which provide ancient variants to the text of MT, and also correct the biblical text when no acceptable readings have been preserved. (These suggestions are named “emendations.”).

Remarkably, although in principle the critical editions remove our thinking from MT by discussing other versions in the apparatus, in practice they make MT even more central than before because they compete with each other in producing ever more precise versions of the Leningrad or Aleppo codex. The Leningrad codex is at the center of the Biblia Hebraica series,[4] while the Aleppo codex is the base for the Hebrew University Bible Project.

Ancient Translations

Skilled persons have been translating the Bible for more than two millennia. With the exception of the LXX translation, the Peshitta, or translations of them or of SP, some version of the (proto-)MT has been the basis of virtually every translation of the Hebrew Bible, Jewish or not.

Since proto-MT was the central Jewish text from the first century CE onwards, several ancient translations were based on that text, reflecting minor differences. This is the case for the Latin Vulgate translation, subsequently used by the Catholic Church, and the Syriac Peshitta, subsequently used by the Syrian Orthodox Church, although the latter deviates occasionally from the proto-MT.

With some exceptions, especially in the Qumran Targum of Job from cave 11 and the Samaritan Targum, all the targumim reflect proto-MT, and this is also the case for the early medieval Arabic translation of parts of Scripture by Saadia (882–942).

Of the ancient translations, the targumim especially came to be identified with Judaism, since they reflected, more or less officially, the exegetical views of the “Rabbis” on the Bible. Some of these targumim offered expanded readings as opposed to translations.

Modern Translations

The influence of the Masoretic Text is so pervasive that most modern translations reflect that text, either exactly or approximately, even though access to alternative versions of the text is now readily available.

An analysis of the textual background of the modern translations shows that we witness passing fashions in the translation of the biblical text. Different tendencies in the inclusion of non-Masoretic readings in the translations are visible throughout the decennia. In the words of Stephen Daley:

English translations from 1611 to 1917 reflect but few textual departures from MT, English translations from 1924 to 1970 reflect a consistently high number, and English translations from 1971 to 1996 reflect a mixed, generally moderate number of departures from MT.[5]

NJPS

The judicious translation of the Jewish Publication Society (NJPS)[6] is a good example of the trend of adhering to MT. More than most translations, the NJPS translation represents the exact text of MT except for those cases in which it considers MT textually corrupt (that is, resulting from an error). In such rare cases, the editors provide editorial notes.[7] Remarkably, a few confessional translations, such as NIV,[8] are closer to MT than NJPS, as they present a literal translation that transfers the linguistic or contextual problems of MT to the translation.

Other Modern Translations

Most modern translations deviate more from MT than NJPS, especially when the translators experienced difficulty with the text of MT. In such cases they adopt details from other textual sources. This practice is usually named an eclectic presentation of the text of the Hebrew Bible, that is, the modern translation chooses from among the textual sources the reading that best represents the presumably original reading, usually adopting readings found in the Septuagint, and in recent years, from the Dead Sea Scrolls as well.

Nevertheless, MT is the main basis of these translations; when they adopt a reading from another source, they sometimes notify the reader in a note, but more often do not. These modern translations thus amount to the reconstruction of the original text of the Bible in translation. Translators do not consider this procedure problematic; they simply feel they are translating MT and occasionally correct its text when to the best of their judgment they are reconstructing the best version imaginable.

That said, this survey has shown that the Masoretic Text holds a central place among the textual witnesses of the Hebrew Bible, ever since it assumed this central status in all streams of Judaism in the first century CE.

Addendum

NJPS and Translating Syntactically Problematic Passages

When encountering textual problems, NJPS uses several techniques when not providing a straightforward translation of MT or replacing MT with an alternative text. It thus obscures the fact that it is not always translating MT. For example, it often playfully manipulates the English translation of textually difficult words to create an acceptable meaning.

Double וַיֹּאמֶר – In Ezek 10:2, MT includes an awkward repetition of wayo’mer (וַיֹּאמֶר), “he said,” which is not reflected in NJPS, which reads “spoke … and said,” translating the same word slightly differently in its two occurrences.[9]

| Literal Trans. | MT | NJPS |

| And he said to the man clothed in linen, and he said… |

וַיֹּאמֶר אֶל הָאִישׁ לְבֻשׁ הַבַּדִּים וַיֹּאמֶר

|

He spoke to the man clothed in linen and said, |

Moving the description of the conquest of Libnah – In another case, the last words in Josh 10:39 MT represent a secondary supplement, lacking in the LXX, and presented here in italics:

| Literal Trans. | MT | NJPS |

| …just as they had done to Hebron, they did to Debir and its king, and as they had done to Libnah and its king. |

…כַּאֲשֶׁר עָשָׂה לְחֶבְרוֹן כֵּן עָשָׂה לִדְבִרָה וּלְמַלְכָּהּ וְכַאֲשֶׁר עָשָׂה לְלִבְנָה וּלְמַלְכָּהּ.

|

…just as they had done to Hebron, and as they had done to Libnah and its king, so they did to Debir and its king. |

NJPS produces a smooth translation by reversing the elements in the verse.[10] The translation does not represent the difficulty of the Hebrew.

In some especially difficult cases, NJPS includes Hebrew variants (non-MT readings) in the translation against its principle of always representing MT; this is accompanied by a textual note.

תַּמְנוּ vs. טַמְנוּ – MT Ps. 64:7 תַּמְנוּ, usually rendered “they have accomplished,” is mentioned only in the note in NJPS, while the translation is based on a nearly identically pronounced variant with a ṭet, namely טַמְנוּ (“they have concealed”).[11]

Cain’s Missing Speech – Gen 4:8 וַיֹּאמֶר קַיִן אֶל הֶבֶל אָחִיו (Cain said to his brother Abel) is not problematic by itself. But Cain’s words are not cited, so this becomes a textually difficult passage. The missing words, probably included in an earlier text but lost in transmission, are preserved in the ancient versions, as mentioned in a note in NJPS. The ellipsis in NJPS “Cain said to his brother Abel … and” reflects an unusual technique attempting to overcome this problem. The resulting translation is artificial, apparently close to MT, but in fact far removed from it.

Adding Hannah – Right after Hannah’s prayer, 1 Sam 2:11 continues with “Then Elkanah went home to Ramah” (וַיֵּלֶךְ אֶלְקָנָה הָרָמָתָה עַל בֵּיתוֹ), without mentioning Hannah. The contextually difficult phrase was corrected in NJPS to “Then Elkanah [and Hannah] went home to Ramah.” The addition of Hannah, albeit in square brackets, allows Hannah to return home with her husband, instead of being stuck forever at Shilo.[12]

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

December 8, 2017

|

Last Updated

March 23, 2025

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Prof. Emanuel Tov is J. L. Magnes Professor of Bible (emeritus) in the Dept. of Bible at the Hebrew University, where he received his Ph.D. in Biblical Studies. He was the editor of 33 volumes of Discoveries in the Judean Desert. Among his many publications are, Scribal Practices and Approaches Reflected in the Texts Found in the Judean Desert, Textual Criticism of the Bible: An Introduction, The Biblical Encyclopaedia Library 31 and The Text-Critical Use of the Septuagint in Biblical Research.

Essays on Related Topics: