Edit article

Edit articleSeries

Habakkuk’s Mythological Depiction of YHWH

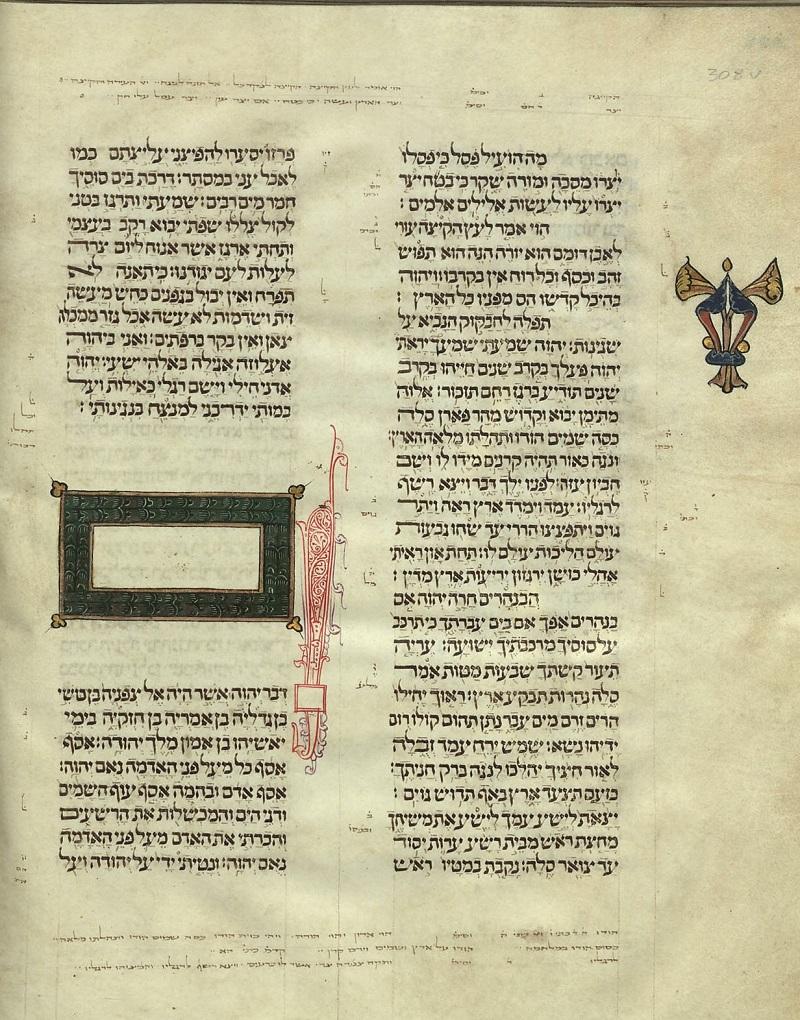

A close-up view of a wall relief depicting the God Assur inside a winged- disc. The hands of Ashurnasirpal II partially appear (making a gesture of worship). Neo-Assyrian period, 865-850 BCE. The British Museum, London. Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin FRCP via wikimedia

Introducing a Lament (vv. 1-2)

Habakkuk 3 begins with its own superscription that contrasts with the superscription for the Book of Habakkuk as a whole.[1]

Book Superscription

הַמַּשָּׂא אֲשֶׁר חָזָה חֲבַקּוּק הַנָּבִיא.

The pronouncement (maśśāʼ)[2] made by the prophet Habakkuk.

Chapter 3 Superscription

תְּפִלָּה לַחֲבַקּוּק הַנָּבִיא עַל שִׁגְיֹנוֹת.

A prayer of the prophet Habakkuk. In the mode of Shigyonot.

The term, shigyonot, appears to be related to Akkadian, šegu, which means “lament.”[3] Habakkuk 3 is a complaint psalm, in which the psalmist calls his own, or his people’s troubles to God’s attention and asks for help. The only other use of this term is in a psalm referred to as shigyon (Psalm 7), which is identified as a shiggayon of David, who sang to YHWH about Kush the Benjaminite (i.e., Saul), who had been trying to kill him.

In the first verse of that psalm, the psalmist asks YHWH, “save me from all who are chasing me and rescue me” (הוֹשִׁיעֵנִי מִכָּל־רֹדְפַי וְהַצִּילֵנִי). Similarly, verse 2 of the Habakkuk psalm asks for YHWH to remember mercy:

חבקוק ג:ב יְ-הוָה שָׁמַעְתִּי שִׁמְעֲךָ יָרֵאתִי יְ-הוָה פָּעָלְךָ בְּקֶרֶב שָׁנִים חַיֵּיהוּ בְּקֶרֶב שָׁנִים תּוֹדִיעַ בְּרֹגֶז רַחֵם תִּזְכּוֹר.

Hab 3:2 O YHWH, I have heard of your reputation! I am in awe, O YHWH, of your deed! In the midst of years, make it live! In the midst of years, make it known! In anger, remember mercy!

The author declares that he knows YHWH’s reputation as a warrior, and that YHWH should bring this power to life, ostensibly to save the psalmist and his people, something he will say explicitly later on.

Although the psalm is an appeal to YHWH to save the psalmist from danger, the core of the psalm is the vision of YHWH’s appearance in verses 3-15, what scholars call a theophany, from the Greek θεοφάνεια meaning “appearance of a god.” In this vision, the psalmist makes use of classic motifs from ancient Near Eastern mythology, known from Egypt, Assyria, Canaan, and elsewhere. The psalmist portrays the divine presence of YHWH in terms analogous to Amon-Re, the sun god of Egypt, Aššur, the warrior god of Assyria, and Baʿal, the Canaanite storm god of Ugarit.

YHWH from the South (v. 3a)

The opening of the theophany (vv. 3-7) describes YHWH in the third person, approaching to confront the threatening enemy:

ג:גa אֱלוֹהַ מִתֵּימָן יָבוֹא

וְקָדוֹשׁ מֵהַר פָּארָן סֶלָה

3:3a God is coming from Teman,

The Holy One from Mount Paran. Selah.

“Teman” refers to the regions south of the land of Israel that lead to the Arabian peninsula, and the parallel term, “Mt. Paran,” is a region identified with the journey of the people through the Sinai wilderness in Numbers 10:12. Paran also appears as a parallel term with Mount Seir and Mount Sinai in Deut 33:2:

דברים לג:ב יְ-הוָה מִסִּינַי בָּא

וְזָרַח מִשֵּׂעִיר לָמוֹ

הוֹפִיעַ מֵהַר פָּארָן

וְאָתָה מֵרִבְבֹת קֹדֶשׁ

Deut 33:2 YHWH came from Sinai;

He shone upon them from Seir;

He appeared from Mount Paran,

And approached from Ribeboth-kodesh,[4]

The verse in Habakkuk and the verse in Deuteronomy both state that YHWH comes from a mountain south of Israel.[5] The connection between Mount Paran in Habakkuk 3:3 and Sinai in Deut 32 is likely the reason Habakkuk 3 was chosen as one of the possible haftarot for Shavuot, which by the Rabbinic period, was understood as celebrating the day the Torah was revealed at Sinai.[6]

Musical Interlude – Sela

The verse continues with the word סלה “sela,” which is likely a signal to the conductor for a musical interlude.[7] That this psalm was meant to be performed with musical instruments is indicated at the end of the psalm, which concludes with:

לַמְנַצֵּחַ בִּנְגִינוֹתָי.

For the leader; with instrumental music.

These words are explicit instructions to the choirmaster concerning the performance of the psalm. The three appearances of the term sela in this psalm, which indicate a musical interlude, are meant to provide dramatic effect after a given passage, in this case, highlighting YHWH’s approach from Teman/Paran.[8]

YHWH Is Like the Sun (v. 3b-4)

The portrayal of YHWH’s approach in verses 3b-7 employs classic mythological motifs from Egypt and Assyria. The description of YHWH’s light and sun rays in verses 3b-4 draws upon solar imagery:

ג:גb כִּסָּה שָׁמַיִם הוֹדוֹ וּתְהִלָּתוֹ מָלְאָה הָאָרֶץ. ג:ד וְנֹגַהּ כָּאוֹר תִּהְיֶה קַרְנַיִם מִיָּדוֹ לוֹ וְשָׁם חֶבְיוֹן עֻזֹּה.

3:3b His majesty covers the heavens, and his praise fills the earth; 3:4 and it is brilliant light, as rays of light come from his hand, and there his strength is hidden.

As the Egyptian god of the sun, Amon-Re is the premier Egyptian deity responsible for bringing sun light, food, order, and wisdom into the world. Hymns to Amon-Re generally use similar motifs, such as Amon-Re as the creator who brings light to the land and journeys across the heavens every day (Papyrus Boulaq 17, 18th dynasty):

The goodly blessed youth to whom the gods give praise;

Who made what is below and what is above;

Who illuminates the two lands, and crosses the heavens in peace.[9]

Likewise, Amon-Re, with his rays of sun light, defeats enemies and brings order to the world:

The goodly ruler, crowned with the White Crown,

the lord of rays, who makes brilliance;

To whom the gods give thanksgiving, who extends his love to whom he loves;

(But) his enemy is consumed by a flame. It is his eye that overthrows the rebels,

That sends its spear into him that sucks up Nun,

and makes the fiend disgorge what he has swallowed.[10]

But Habakkuk’s psalm also employs Mesopotamian imagery of the Assyrian god, Aššur, who is frequently depicted as riding through the skies in a winged sun disk with his bow drawn as he leads the Assyrian army to victory over its enemies.[11]

YHWH Is Lethal (vv. 5-7)

The Psalmist next makes clear the lethal nature of YHWH’s approach:

ג:ה לְפָנָיו יֵלֶךְ דָּבֶר וְיֵצֵא רֶשֶׁף לְרַגְלָיו. ג:ו עָמַד וַיְמֹדֶד אֶרֶץ רָאָה וַיַּתֵּר גּוֹיִם וַיִּתְפֹּצְצוּ הַרְרֵי עַד שַׁחוּ גִּבְעוֹת עוֹלָם הֲלִיכוֹת עוֹלָם לוֹ.

3:5 Before him goes dever (pestilence), and resheph (plague) goes forth at his feet; 3:5 He stands and measures the earth, he looks and he sees nations; And the ancient mountains are shattered, the eternal hills sink low.

Similar language appears in Mesopotamian flood narratives, such as the one incorporated into the Gilgamesh epic, as the flood advances to inundate and punish the earth:

With the first glow of dawn, a black cloud rose up from the horizon;

Inside it, Adad, thunders, While Shullat and Hannish go in front;

Moving as heralds over hill and plain;

Erragal tears out the posts; forth comes Ninurta and causes the dikes to follow;

The Annunaki lift up the torches, setting the land ablaze with their glare.[12]

This subsection concludes by describing how YHWH’s travels from the south to his people disrupted the dwelling places of the locals through whom he crossed:

ג:ז תַּחַת אָוֶן רָאִיתִי אָהֳלֵי כוּשָׁן יִרְגְּזוּן יְרִיעוֹת אֶרֶץ מִדְיָן.

3:7 As a scene of havoc I behold the tents of Cushan; Shaken are the pavilions of the land of Midian!

YHWH’s Assault on the Elements

The second half of the theophany (vv. 8-15) portrays YHWH’s assault against the mythological enemy. The switch in topic is signaled by employing second person address forms to portray YHWH’s victory:

ג:ח הֲבִנְהָרִים חָרָה יְהוָה אִם בַּנְּהָרִים אַפֶּךָ אִם בַּיָּם עֶבְרָתֶךָ כִּי תִרְכַּב עַל סוּסֶיךָ מַרְכְּבֹתֶיךָ יְשׁוּעָה. ג:טa עֶרְיָה תֵעוֹר קַשְׁתֶּךָ שְׁבֻעוֹת מַטּוֹת אֹמֶר סֶלָה

3:8 Is your anger against the Rivers, O YHWH? Or against the Rivers is your wrath? Or against the Sea is your rage? That You are driving Your steeds, Your victorious chariot? 3:9a All bared and ready is Your bow. Sworn are the rods of the word. Selah.

The psalmist here is asking YHWH rhetorically, whether his enemies are really the rivers and the sea? Such a mythological image of battling the elements accentuates the raw power of YHWH and his bow, and appears in other poetic passages in the Bible and in ANE mythology.

For example, in the Ugaritic Baʿal Epic, the Canaanite god, Baʿal, defeats his enemy, Yamm (the Sea), also known as Judge Nahar (the River), as he uses his war clubs to strike him down. When the craftsman god, Kothar wa-Khasis arms Baʿal with his war clubs, he describes Baʿal’s impending victory:

Kothar brings down two clubs, and gives them names,

Thou, thy name is Ayamur (Driver), Ayamur, drive Yamm (Sea)!

Drive Yamm from his throne, Nahar (River) from his seat of dominion!

Do thou swoop in the hand of Baal, like an eagle between his fingers![13]

The description of YHWH’s bow and rods is followed by another sela. Following this musical interlude, it continues with the mythological depiction:

ג:טb נְהָרוֹת תְּבַקַּע אָרֶץ. ג:י רָאוּךָ יָחִילוּ הָרִים זֶרֶם מַיִם עָבָר נָתַן תְּהוֹם קוֹלוֹ רוֹם יָדֵיהוּ נָשָׂא. ג:יא שֶׁמֶשׁ יָרֵחַ עָמַד זְבֻלָה לְאוֹר חִצֶּיךָ יְהַלֵּכוּ לְנֹגַהּ בְּרַק חֲנִיתֶךָ.

3:9b Rivers split the earth, 3:10 The mountains rock at the sight of You, a torrent of rain comes down; Loud roars the deep, the sky returns the echo. 3:11 Sun and moon stand still on high as Your arrows fly in brightness, Your flashing spear in brilliance.

Here we see the chaos from YHWH’s attacks: Rivers break through the earth, mountains shake, the sky spews forth rain and thunder, all while the sun and moon look on, watching as YHWH’s arrows and spears flash in their light.

YHWH Fights the Psalmist’s Earthly Enemies

At this point, the psalmist turns to a depiction of YHWH’s enemies on earth:

ג:יב בְּזַעַם תִּצְעַד אָרֶץ בְּאַף תָּדוּשׁ גּוֹיִם. ג:יג יָצָאתָ לְיֵשַׁע עַמֶּךָ לְיֵשַׁע אֶת מְשִׁיחֶךָ מָחַצְתָּ רֹּאשׁ מִבֵּית רָשָׁע עָרוֹת יְסוֹד עַד צַוָּאר סֶלָה.

3:12 You tread the earth in rage, you trample nations in fury. 3:13 You have come forth to deliver Your people, to deliver Your anointed. You will cleave the head from the house of the wicked! Exposing the foundation down to the neck! Selah.

This is the first time the psalmist directly refers to his desire for YHWH to save him, albeit indirectly: YHWH is coming to save his people. The description of this battle ends with mythic imagery reminiscent of what we saw about in the Baʿal Epic, with YHWH splitting the enemy’s head all the way down to the base of the neck:

Strike the pate of Prince Yamm, between the eyes of Judge Nahar!

Yamm shall collapse and fall to the ground![14]

Here too the musical interlude sela signals dramatic effect, after which the theophany continues with the theme of YHWH killing his enemies:

ג:יד נָקַבְתָּ בְמַטָּיו רֹאשׁ (פרזו) [פְּרָזָיו] יִסְעֲרוּ לַהֲפִיצֵנִי עֲלִיצֻתָם כְּמוֹ לֶאֱכֹל עָנִי בַּמִּסְתָּר.

3:14 You will crack (his) skull with Your bludgeon. Blown away shall be his warriors, whose delight is to crush me suddenly, to devour a poor man in an ambush.

Here the psalmist describes the enemy’s warriors as threatening him personally, as a parallel to his previous description of the enemy’s threatening the people as a whole.

The theophany closes with more mythological imagery describing YHWH’s chariot riding over the sea, stirring the waters:

ג:טו דָּרַכְתָּ בַיָּם סוּסֶיךָ חֹמֶר מַיִם רַבִּים.

3:15 You will make Your steeds tread the sea, stirring the mighty waters.

The Psalm’s Conclusion: Confidence in YHWH

Habakkuk’s psalm concludes in verses 16-19a with the psalmist’s expression of confidence in YHWH’s coming deliverance. He first expresses how, despite how much he fears his enemies, he awaits the day of their distress:

ג:טז שָׁמַעְתִּי וַתִּרְגַּז בִּטְנִי לְקוֹל צָלֲלוּ שְׂפָתַי יָבוֹא רָקָב בַּעֲצָמַי וְתַחְתַּי אֶרְגָּז אֲשֶׁר אָנוּחַ לְיוֹם צָרָה לַעֲלוֹת לְעַם יְגוּדֶנּוּ.

3:16 I heard and my bowels quaked, my lips quivered at the sound; rot entered into my bone, I trembled where I stood. Yet I wait calmly for the day of distress to come up against the people who attack us.

He continues by expressing that no matter how terrible the situation is now, he is confident that YHWH is on his way to deliver him and his people:

ג:יז כִּי תְאֵנָה לֹא תִפְרָח וְאֵין יְבוּל בַּגְּפָנִים כִּחֵשׁ מַעֲשֵׂה זַיִת וּשְׁדֵמוֹת לֹא עָשָׂה אֹכֶל גָּזַר מִמִּכְלָה צֹאן וְאֵין בָּקָר בָּרְפָתִים. ג:יח וַאֲנִי בַּי-הוָה אֶעְלוֹזָה אָגִילָה בֵּאלֹהֵי יִשְׁעִי. ג:יטa יְ-הוִה אֲדֹנָי חֵילִי וַיָּשֶׂם רַגְלַי כָּאַיָּלוֹת וְעַל בָּמוֹתַי יַדְרִכֵנִי.

3:17 Though the fig tree does not bud and no yield is on the vine, though the olive crop has failed and the fields produce no grain, though sheep have vanished from the fold and no cattle are in the pen, 3:18 Yet will I rejoice in YHWH, exult in the God who delivers me. 3:19 YHWH, my Lord, is my strength: He makes my feet like the deer’s and lets me stride upon the heights.

The concluding metaphor likens the psalmist to a deer jumping across mountains in joy.

Parochial Theme – Universal Imagery

Habakkuk 3 is a lament that expresses the poet’s desire for YHWH to protect his people from an oppressive enemy. He depicts this salvation in mythological terms, imagining the awesome power of YHWH, coming up from his home in the south, trampling seas and mountains, and smashing the skulls of Judah’s enemies. Although such a contention is of special significance to the people of Judah, the poet’s style demonstrates that Hebrew psalmody drew upon the broader hymnic and mythological traditions of the ancient Near East, including Egypt, Mesopotamia, and Canaan.

Afterword

Habakkuk 3 in Context: What Enemy Does Habakkuk Fear?

The psalmist appeals to YHWH to deliver the nation from an oppressor, much as YHWH has done in the past, e.g., at the Red Sea during the Exodus from Egypt. But who is the oppressor? The psalm never says, but in the context of the book, the psalm is referring to the Babylonians.[15]

Habakkuk 1-2 presents a dialog between the prophet and YHWH concerning the threat posed to Jerusalem and Judah by the Chaldeans, i.e., the Neo-Babylonian Empire of Nebuchadnezzar, which took control of Jerusalem and Judah in 605 B.C.E. Habakkuk is alarmed to learn that YHWH was the one who brought about the Babylonian threat, but he is assuaged when YHWH assures him that the Babylonians will ultimately fall as a result of their greed and oppressive character.

Habakkuk 3 expresses the same hope as Habakkuk 1-2, viz., that YHWH will act on behalf of the nation to deliver it from its enemies, namely, the Chaldean threat. If this is so, the reality fell far short of psalmist’s hopes, as in 586 B.C.E., the Babylonian army conquered Judah, destroying Jerusalem and its Temple and exiling much of its population.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

May 18, 2018

|

Last Updated

December 1, 2025

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Prof. Marvin A. Sweeney is Professor of Hebrew Bible at the Claremont School of Theology at Willamette University, Salem, Oregon. His Ph.D. is from Claremont Graduate University. He is the author of sixteen volumes, such as Tanak: A Literary and Theological Introduction to the Jewish Bible; Reading the Hebrew Bible after the Shoah: Engaging Holocaust Theology; and Jewish Mysticism: From Ancient Times through Today.

Essays on Related Topics: