Edit article

Edit articleSeries

How Jewish Was Herod?

Herod, 1886-1894 James Tissot. Brooklynmuseum.org

Herod’s Background

Herod, one of the greatest and most controversial kings of Judea, was born in the year 73/72 B.C.E. to a family of Idumean converts.[1] His grandfather, Antipas, was the first to convert to Judaism under the wave of conquests led by the Hasmonean ruler, John Hyrcanus (134–104 B.C.E.). Later, during the reign of John Hyrcanus’ son Alexander Jannaeus (103–76 B.C.E.), Josephus tells us (Ant. 14:10),

That king Alexander and his wife made him (=Antipas) general of all Idumea, and that he made a league of friendship with those Arabians, and Gazites, and Ashkelonites, that were of his own party, and had, by many and large presents, made them his fast friends.

Thus, began the long affiliation of this family with that of the ruling house of Judea. Antipas’ son, Antipater, was a friend to Alexander Jannaus’ son, Hyrcanus (Ant. 14:8), and succeeded in worming his way into his good graces and advising him to challenge his brother for rulership.

Antipater’s two oldest sons were Phasaelus, perhaps a Hebrew name (פצאל) meaning “El saves” or “El sets free,” and Herod, a Greek name (Ἡρῴδης) meaning either “son of a hero” or “like a hero.” As Antipater’s star rose, he brought his sons into the political fold, and they served as political advisors and military commanders. Armed with wit, cunning, sharp minds, and bags of charisma, the three men managed to become an indispensable fixture in the daily lives of the royal family.

When Antipater understood that the Romans, rather than the Hasmoneans, were to be the real powers in the area, he transferred his allegiance to them, and following assistance he gave to Julius Caesar against Pompey, was rewarded with Roman Citizenship and named procurator of Judea (i.e., the agent in charge under Rome), with the Hasmoneans taking only the title of high priest (Ant. 14:143). In turn, Antipater named Phasaelus governor of Judea and Herod governor of the Galilee.

In 40 B.C.E., a scion of the Hasmonean family named Antigonus made a treaty with the Parthians and took Jerusalem back from Rome. Phasaelus was taken and committed suicide, but Herod led an army and laid siege to Jerusalem, retaking it for Rome in 37 B.C.E. This same year, at the age of 35, Herod married Miriam the Hasmonean, daughter of Alexander Jannaeus, the patron of Herod’s grandfather. Thus, Herod integrated himself further into the famous dynasty, and made it possible for him to take the leap from procurator to king.

A Complex Relationship with Judaism

One of the first things Herod did when coming to full power was to dismiss the priests associated with the Hasmonean dynasty, and elevate priests from Jewish families that came from the diaspora. Thus, Herod created a ruling religious class that was loyal to the king and was more open-minded than its predecessor.[2]

One cannot blame Herod for seeking a more sympathetic religious order. Both major sects at the time, the Pharisees and the Sadducees, were unhappy with the king in some way; he came from the wrong background, the wrong family, had the wrong upbringing, and his relationship with Judaism was difficult.

Herod’s Jewish identity was always a sore point; he was simply not Jewish enough for most of his reluctant subjects. The Gospel of Matthew (2:1–20), the Talmud (b. Baba Batra 4b), and even Josephus (Ant. 17:304–308) at times, label Herod as a cruel king whose legitimacy to the throne was questionable, at best. The Sages, writing centuries after Herod’s lifetime, describe Herod as being the “Hasmonean slave,” showing how Jewish tradition doubted Herod’s Jewishness.[3]

Certainly, his ethnic and religious background was complicated: On his father’s side he was an Idumean-Jew, from a family of Idumean converts; on his mother’s side, he was Nabatean—his mother was a Nabatean Princess—an Arabic tribe in southern Jordan (near Petra).[4] Moreover, as an aristocrat in Judea, he had both a Hellenistic and a Jewish upbringing; it is no wonder he had a complicated relationship with religious identity.

While the literary sources debate Herod’s Jewishness, much of this debate stems from the ideological stance of the author and not a dispassionate look at Herod’s life and behavior. Thus, a different tool can help us evaluate Herod’s relationship to his Judaism, namely, archaeology. Luckily, as Herod was one of the greatest builders of all time, he left us a lot of material with which to work.

Upholding Purity Laws

The Second Temple period is well known for its severe and somewhat obsessive, purity laws. The need to be cleansed and pure enough to worship at the Temple dominated the lives of Jews in Judea. Evidence for this can be found in the abundant amount of mikvaot (ritual baths) spread throughout the country, most of which were found in Jerusalem.[5]

Mikvaot were found in all of Herod’s palaces, even at the more private ones, such as the Promontory Palace in Caesarea Maritima. Some of the mikvaot were of a small, domestic size, such as the one located at the lower terrace of the Northern Palace in Masada, indicating that they were probably used by the inner family, perhaps even by the king himself.[6]

Chalk Vessels: Insusceptible to Impurity

As part of this emphasis on purity, stone vessels made of soft chalk, a substance that does not pass ritual impurity, began to appear in Jewish settlements. When such vessels are found at an excavation, it points to a strictly Jewish lifestyle, especially when the same place has mikvaot.

Such vessels are found in at least three of Herod’s palaces. Although these palaces were in use after Herod’s lifetime, and thus the findings do not prove that he used such vessels, the ensemble in the Third Winter Palace in Jericho can be directly attributed to Herod’s lifetime.[7] The fact that such vessels, which can only be found in a Jewish context, were unearthed at the Herodian strata, means that the king and his family did uphold some of the purity laws of their time.[8]

No Images: Honoring the Decalogue

The Decalogue states:

שמות כ:ד לֹא תַעֲשֶׂה לְךָ פֶסֶל וְכָל תְּמוּנָה אֲשֶׁר בַּשָּׁמַיִם מִמַּעַל וַאֲשֶׁר בָּאָרֶץ מִתַָּחַת וַאֲשֶׁר בַּמַּיִם מִתַּחַת לָאָרֶץ.

Exod 20:4 You shall not make for yourself a sculptured image, or any likeness of what is in the heavens above, or on the earth below, or in the waters under the earth

Although the exact parameters of the prohibition have been interpreted differently in various periods, archaeological evidence suggests that the Hasmoneans understood the prohibition to include any form of artwork depicting real objects in the world. Thus, even though the Hasmonean kings were very fond of the Hellenistic lifestyle, they kept the ban on anthropomorphic and zoomorphic representation by decorating their palaces with very elaborate, geometric mosaics. Herod kept the same tradition almost to a tee.

His beautiful palaces were home to lovely, abstract wall paintings drawn in the Second Pompeian Style, and his floors sported beautiful mosaics, all according to the latest fashion in Rome; black and white honeycomb design in the Northern Palace, colorful geometrical assortment in the Promontory Palace and apparently in the Jerusalem Temple itself.[9]

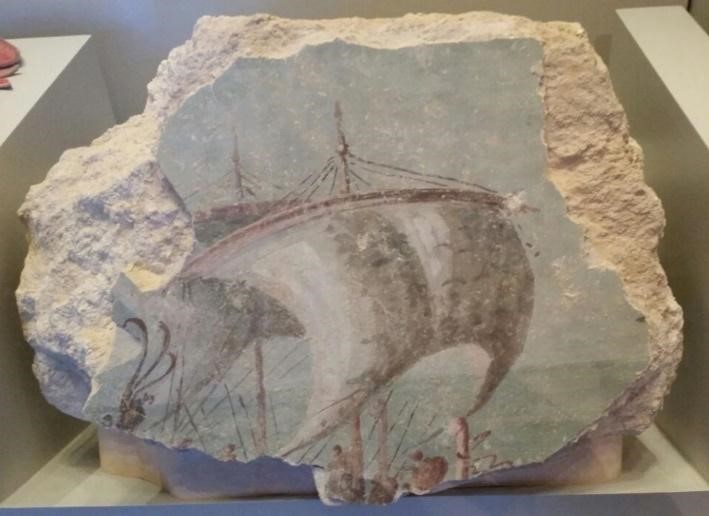

The Herodium Triclinum: An Exception

One exception, however, to Herod’s general adherence to this commandment was found during the recent excavations of the theatre in Lower Herodium. The team of archaeologists uncovered the royal triclinium (dining room), which was decorated with beautiful wall paintings depicting scenes of a sea battle (probably the famous battle of Actium), a sacred landscape, and men in a symposium.[10] It is the only place known to date, in which Herod chose to disregard the ban he so carefully followed in all other projects.[11]

Renovating the Temple and the Royal Portico

In the year 20/19 B.C.E. Herod undertook the most grandiose and the most important scheme of his life: renovating the Jewish Temple on the Temple Mount. The span of this project was so vast, that decades later when it was burned to the ground in the year 70 C.E. by Vespasian and his Legions, it was not yet completely finished.

Undertaking such a delicate project, with all the difficulties that came with it, may demonstrate the respect the king held towards the religion he was born into. One may assume that in reconstructing the most important building to Judaism, Herod tried to appease his Jewish subjects and their religious leaders.[12] According to Josephus (Ant. 15, 420), Herod himself refrained from entering the Temple and kept to the Royal Portico, i.e., the basilica on the Temple Mount in which he was personally involved with planning.[13]

Did Herod Keep Kosher?

Another case in which Herod’s behavior is a mix of Jewish and Hellenistic is how he related to the various food rules that make up the laws of kashrut.

No Pork

Herod executed his wife, Miriam, and her mother Salome, in 29 B.C.E. The next year, he murdered his brother-in-law Kostabar. These acts stemmed from his paranoia about relatives wishing to take away his throne. This paranoia only worsened over time, leading to his most famous act, namely the accusation of high treason against two of his sons, Alexander and Aristobolus, and their subsequent execution in 7 B.C.E.

To proceed with the trial (which took place in the Roman court in Beirut), he needed to get permission from Augustus Caesar, which he received. The incident led to Augustus’ famous quip,

It is better to be Herod’s pig (Greek: hua) than son (Greek: huia).[14]

The pun is based on the assumption that, as Herod was a Jew, he would not eat pork, and thus, his pig would be safe from the butcher’s knife, unlike his own flesh and blood.

Kosher Fish?

Having close ties to the emperor and his family was very beneficial to Herod’s lavish lifestyle. He imported many unique goods, such as Italian marble, the famous cinnabar pigment from the imperial quarries in Spain, Roman teams of artists and architects, and, of course, decadent food.

The King of Judea and his revered guests enjoyed delicacies such as Italian apples and Spanish garum, which is a fermented fish sauce used as a condiment. Scientists who studied these containers of garum determined that Herod’s was an unusual blend, containing only kosher fish, in contrast to the usual recipe.[15] This shows that the people exporting garum to Herod knew about this Jewish prohibition and assumed (or were told explicitly) that Herod followed it, and that he was willing to pay extra for this.

Gentile Wine

Another luxury product that Herod imported was Italian and Aegean wines.[16]

Here we have an interesting development pointing in the opposite direction of the garum: Herod drank gentile wine, a product banned by observant Jews as early as Daniel 1:8 and certainly by Herod’s lifetime.

Roman Projects and Fealty to the Emperor

Herod’s most striking deviation from Jewish practice had to do with his loyalty to his Roman patrons. Herod had many subjects, not all of whom were Jewish. Together with Octavian’s pardon at Actium,[17] Herod received quite a lot of conquered territories that had once been part of Hasmonean Judea but had been lost over the years. Many of these territories included gentile cities.

Never one to forget his good fortune, Herod erected at least three temples dedicated to Rome and Augustus in the cities of Caesarea Maritima, Sebaste (Samaria), and Panias. He also added theatres, gymnasia and Nymphaea,[18] which were frowned upon by his Jewish subjects. His purpose was to make those cities as Roman as possible, disregarding the religious bans he had to keep within his Jewish settlements against such buildings.

The Golden Eagle Incident

The most famous example of Herod’s flouting Jewish sensibilities to honor his patrons is when, at some point towards the end of his life, he decided to hang a large golden eagle at the main gate leading to the Temple, in order to show his fealty to Rome. This enraged his Jewish subjects, and a plot to take down the offending statue was concocted. When Herod found out about the plan, he reacted badly and had the “traitors” burned alive, in order to teach his people a lesson.[19]

It’s Complicated

King Herod was a very complex character. From his Idumean roots and his Nabatean mother to his Hellenistic upbringing and the religion forced upon his ancestors, his was a life of contradictions. The evidence garnered above paints a complex portrait of Herod’s Jewish observance. If we look back at the rather confusing and contradictory evidence to the question of Herod’s Jewishness, the most reasonable characterization of his relationship with Judaism is: it’s complicated.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

September 22, 2019

|

Last Updated

December 2, 2025

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Evie Gassner is a Ph.D. candidate in archaeology at Ariel University, and holds an M.A. from the Hebrew University. She is part of the Givat Ze’ev expedition and was previously part of the Horvat Midras and David expeditions. Gassner’s research focuses on Herodian landscape archaeology.

Essays on Related Topics: