Edit article

Edit articleSeries

What We Learned from Sifting the Earth of the Temple Mount

Digging in front of Solomon’s Stables

How the Sifting Project Came About[1]

Despite Jerusalem being one of the most excavated cities in the world, for a variety of religious and political reasons, the Temple Mount has never been systematically excavated.[2]The project that we run, the Temple Mount Sifting Project, only came about accidentally, as a result of surprising circumstances.

As a consequence of the Israeli victory over Jordan in the Six Day War, on June 7, 1967, Israel unified Jerusalem and gained sovereignty over the Old City of Jerusalem. Soon after, on June 17, Minister of Defense Moshe Dayan returned the managerial control of the Temple Mount to the Jordanian Waqf, the Islamic Religious Trust appointed by the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan, as the civil administration of the Temple Mount.

The Dump

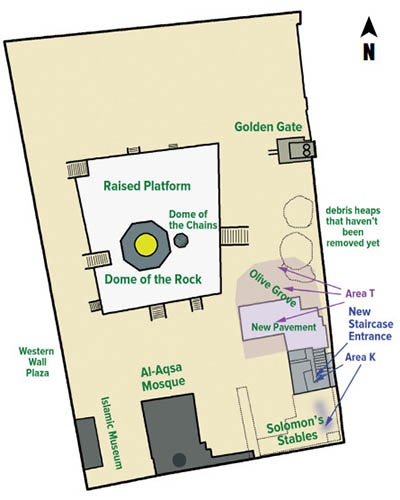

In the late 1990s, under the auspices of the Waqf, the Northern Branch of the Islamic Movement in Israel[3]decided to convert a large underground structure, named by the Crusaders “Solomon’s Stables,” into a huge new mosque.[4] The Northern Branch of the Islamic Movement brought heavy machinery to bulldoze a massive area in the southeastern corner of the Temple Mount for a stairway down to the new underground Al-Marwani Mosque there.

In the late 1990s, under the auspices of the Waqf, the Northern Branch of the Islamic Movement in Israel[3]decided to convert a large underground structure, named by the Crusaders “Solomon’s Stables,” into a huge new mosque.[4] The Northern Branch of the Islamic Movement brought heavy machinery to bulldoze a massive area in the southeastern corner of the Temple Mount for a stairway down to the new underground Al-Marwani Mosque there.

Working day and night for three days, without any archaeological supervision and in violation of the Antiquities Law of the State of Israel,[5] they created space for a stairway down to the mosque. In a later phase, the ground level in the southeastern area of the Temple Mount, north of the new Stairway, was lowered by about 1.5 feet to enable paving large parts of the area. About 400 truckloads (approximately 9,000 tons) of archaeologically rich soil were removed, and unceremoniously dumped, mostly in the nearby Kidron Valley.

The Sifting Project

The police were aware of the dumping of this earth, but did not share it publicly. Some watchful citizens noticed the trucks going in and out of the Temple Mount and realized what was going on, and began to publicize it. One of the authors (Zachi Dvira), then a young student, heard about this and realized the significance of the dump, and contacted the other author (Gabriel Barkay) to partner with him.

In late 1999, we brought the news to the media and the public’s attention. The news caused an outcry and, after overcoming many bureaucratic obstacles, in 2004 we raised the initial funds (provided by the Heritage Foundation of Abraham and Frieda Wiener) and obtained a permit to systematically sift the earth from the dump in the Kidron Valley.

Since it was logistically impossible to sift the earth near where it was dumped, in late 2004 we began transferring this archeologically significant earth—322 truckloads full—to the Tzurim Valley National Park, overlooking the Old City of Jerusalem.

Excavation vs. Sifting

In a typical excavation, archeologists try to understand a site and its artifacts broadly. They dig slowly and methodically, isolating each archaeological layer, learning what structures were there, and what they contained.[6] Objects found in situ, i.e., in their archaeological context, can be dated in relation to the layer where they are found, and what is above and below. None of this is possible when sifting through a pile of relocated earth. Nevertheless, this sifting project is of value, and different than acquiring ancient artifacts on the antiquity market, since we know the original location from where the dirt was taken.

In many ways, the Sifting Project is like an archaeological survey. In a survey, archaeologists comb a given area’s surface looking for artifacts. Surface artifacts are generally out of stratigraphic context, but picking up all visible artifacts in a given area typically yields a representative sample.

Similarly, the Sifting Project offers us a representative sample of what lay below the Temple Mount, at least in this sector of it, and a glimpse at ancient artifacts from the Jerusalem Temple, as well as from the Roman, Christian, and Muslim periods that followed. What we recovered represents the first-ever archaeological data originating from within the soil of the Temple Mount.

Methods

We initially tried the standard archaeological sifting method, which is conducted dry. A pile of dirt is put on a large sieve; when the dirt falls through the holes, what is left are rocks, plant debris, and, hopefully, archaeological finds. But the initial results were disappointing; we were not finding anything.

We then changed tactics and used water in the sifting process. We suspected that the large amounts of ash and dust we were finding made it impossible to tell if something was an archaeological treasure or merely a “plain old rock.” Gradually, we refined the wet sifting technique, which became our standard method.[7] The results were very successful. We retrieved hundreds of thousands of artifacts and identified, sorted, dated, cataloged and documented them for future publication in a comprehensive archaeological report.

By 2017, about 70% of the material had been sifted, and we took a pause to engage in the comprehensive study and publication of the finds (We plan to resume the sifting once the funding for the publication is secured).[8]

The most common finds are pottery fragments, pieces of glass vessels, coins, metal objects, bones, worked stones and mosaic tesserae, though we have recovered numerous other artifacts. Most of the finds date from the First Temple Period onward, that is, the 10th century B.C.E. (biblically speaking, the time of David and Solomon), and continue until the present. The finds that predate the First Temple Period are scarce, implying that the city extended northward only from this period on, and not earlier.[9]

First Temple Finds

About 15 percent of the diagnostic pottery pieces[10] can be dated to the First Temple Period. The finds also include five arrowheads, three are made of iron and the other two are made of bronze. One of these bronze arrowheads dates to the beginning of the First Temple Period (10th century BCE) and is Judahite, the other dates to the last days of the Temple and is Babylonian (photo). It was likely shot into the city by the Babylonian army during the attack which led to the destruction of the Temple by Nebuchadnezzar in 586 B.C.E.

About 15 percent of the diagnostic pottery pieces[10] can be dated to the First Temple Period. The finds also include five arrowheads, three are made of iron and the other two are made of bronze. One of these bronze arrowheads dates to the beginning of the First Temple Period (10th century BCE) and is Judahite, the other dates to the last days of the Temple and is Babylonian (photo). It was likely shot into the city by the Babylonian army during the attack which led to the destruction of the Temple by Nebuchadnezzar in 586 B.C.E.

Seals and Bullae

We have found over 30 Iron Age stone signets or seals, bullae (clay pressed with a signet ring and used as a seal) and fragments of bullae. Among them was a bulla dated to the seventh century B.C.E. (photo) bears the Hebrew inscription

…[ל]

…[belonging to]

[הצ]ליהו

[hz]lyahu

[בן] אמר

(son of) Immer.

Immer (אִמֵּר) is the name of a well-known priestly family from the end of the First Temple period (ca. seventh–sixth centuries B.C.E.) and the Post-Exilic period (1 Chronicles 24:14). Pashhur son of Immer is mentioned in Jeremiah 20:1:

Immer (אִמֵּר) is the name of a well-known priestly family from the end of the First Temple period (ca. seventh–sixth centuries B.C.E.) and the Post-Exilic period (1 Chronicles 24:14). Pashhur son of Immer is mentioned in Jeremiah 20:1:

…פַּשְׁחוּר בֶּן אִמֵּר הַכֹּהֵן וְהוּא פָקִיד נָגִיד בְּבֵית יְ-הוָה…

Pashhur son of Immer, the priest who was chief officer of the House of YHWH…

The impression on the back of this bulla indicates that it was attached to a coarse fabric sack.

Such seals and bullae are known from ancient Near Eastern treasuries, and the titles pakidand nagid are also common in the Bible among treasury overseers. Thus, these bullae presumably sealed precious goods kept in the Temple treasury, which was managed by priests from the house of Immer. This seal impression from the Temple Mount directly attests to the administrative activity that occurred on the Temple Mount during the last days in the First Temple.

It is hardly surprising that the First Temple Period finds include seals, bullae, and weights. A great deal of administrative activity occurred here; in addition to the Temple, the Temple Mount included other governmental buildings and royal palaces.

Terracotta Figurines and JPFs

At first, we were surprised to find more than 170 fragments of terracotta figurines, mostly quadrupeds (most are horses, as well as sheep, cows, etc.), but also Judahite pillar female figurines, which date to the First Temple Period. Such figurines are common in all Iron Age excavations in Jerusalem and the Kingdom of Judah in the late eighth and throughout the seventh centuries.[11] They are usually found fragmented, suggesting that they were deliberately broken in antiquity as part of a ritual act. Several scholars have tied this phenomenon to the iconoclastic reforms of King Josiah at the end of the seventh century B.C.E., which included the smashing of idols and dumping them in the Kidron Valley (2 King 23:4–13; 2 Chronicles 34:3–8).[12]

Second Temple Period

We found artifacts from all phases of the Second Temple period (515 B.C.E.–70 C.E.) — from the Persian Period until the Roman Period. The soil contained large amounts of ash, and many of the finds have signs of burning, probably from the vast conflagration that ended the First Jewish Revolt against Rome in 70 C.E. The many burnt bones of sheep, goat and cattle may be the remains of sacrifices offered on the Temple’s altar.

We have also found stone fragments that must have been from elaborate buildings. We can identify architraves, bases, capitals and column drums. Some of these may even have originated from the Temple structure itself.

Herod’s Tiles

We have also discovered hundreds of opus sectile stone tiles from the time of the Herodian expansion of the Temple Mount. Opus sectile (Latin for “cut work”) is a technique of paving floors in lavish geometric patterns using meticulously cut and polished polychrome tiles. Many of the tiles have been dated to the Late Second Temple Period based on parallels found in Herodian palaces (this study was led by Frankie Snyder).

In the floor patterns, each tile was surrounded by tiles of contrasting colors. Dark tiles were frequently made from local bituminous chalk. Some of the contrasting light-colored tiles were made from imported alabaster and marble. The tiles’ dimensions are based on fractions of the Roman foot (c. 11.65 in).

Several Herodian floors use the specifically shaped “Herod’s triangle”—a triangle whose base is equal to its height, like a triangle constructed inside a square. This triangle with the unusual corner angles of 52°-64°-64° was very common in Herodian patterns but was rarely seen in floors elsewhere in the Roman world. When used in a pattern, the Herod’s triangles cause adjacent tiles to also have unusual, but mathematically recognizable, corner angles.

On the Temple Mount, this Herod’s triangle appears to have been used in a way similar to what we find at some of Herod’s palaces. Herod’s triangles can be used to generate fascinating designs. For example, if four Herod’s triangles are drawn inside a 1-Roman-foot square, this creates a versatile template from which to generate several tile patterns. By adding a small square in the center, variations of a popularly used four-pointed-star pattern can be produced.

As a result of this discovery, we better understand what Flavius Josephus meant when he wrote about the open courts surrounding the Temple: “Those entire courts that were exposed to the sky were laid with stones of all sorts (Josephus, War of the Jews 5.5.2)” We recently proposed several reconstructions of these floor patterns (photo).

Coins

To date, the Sifting Project has recovered more than 6,000 coins, ranging from the first Judean coins minted during the Persian period (tiny silver Yehud coins dating from the fourth century B.C.E.)[13] to others minted in modern times. These coins attest to the rich past of the Temple Mount.

A particularly exciting find is a rare silver coin minted during the first year of the Great Jewish Revolt against Rome (66/67 C.E.) (photo). The coin features a branch with three pomegranates and an inscription in ancient Hebrew script reading “holy Jerusalem” [14](ירשלם קדשה). The reverse side of the coin features an omer (ancient half-cup measuring unit) and is inscribed “half shekel” (חצי השקל). The coin is well preserved although it bears scars of the conflagration that destroyed the Second Temple in 70 C.E.

A particularly exciting find is a rare silver coin minted during the first year of the Great Jewish Revolt against Rome (66/67 C.E.) (photo). The coin features a branch with three pomegranates and an inscription in ancient Hebrew script reading “holy Jerusalem” [14](ירשלם קדשה). The reverse side of the coin features an omer (ancient half-cup measuring unit) and is inscribed “half shekel” (חצי השקל). The coin is well preserved although it bears scars of the conflagration that destroyed the Second Temple in 70 C.E.

These half-shekel coins were used to pay the Temple tax during the Great Revolt, replacing the Tyrian shekel used previously (the Jews did not mint their own coins, and this international coin fit the tradition of what the value of a half shekel should be). It appears that the new half-shekel coins were minted by the Temple authorities on the Temple Mount itself. This half-shekel tax for the sanctuary, mentioned in the Book of Exodus (30:13–15) and is the main topic of Tractate Shekalim, required every male to pay half a shekel to the Tabernacle once a year.

Later Periods

Late Roman – Other finds reflect life on the Temple Mount in later periods. Objects from the Late Roman Period include bone objects (like hair pins) and bone workshop’s waste, gem stones with designs, gaming pieces (photo), fragments of clay figurines, and several roof tile fragments with impressions of the Tenth Roman Legion (which destroyed the Temple and was stationed in Jerusalem after its destruction).

Late Roman – Other finds reflect life on the Temple Mount in later periods. Objects from the Late Roman Period include bone objects (like hair pins) and bone workshop’s waste, gem stones with designs, gaming pieces (photo), fragments of clay figurines, and several roof tile fragments with impressions of the Tenth Roman Legion (which destroyed the Temple and was stationed in Jerusalem after its destruction).

Byzantine – Finds from the Byzantine Period (324–638 C.E.) include about half a million mosaic tesserae which are unique in their size and style, thousands of roof tile fragments, pieces of Corinthian capitals and chancel screens from church structures and floor tiles. The plethora of Byzantine-period artifacts stands in contrast to the commonly held view that in the Byzantine era the Temple Mount was desolate or, according to some sources, a garbage dump.[15] Clearly, this view is mistaken.

It is especially worth noting that the remains of church structures contradict the commonly held belief that there were no churches on the Temple Mount during this period. In fact, one of the authors (Dvira) discovered unpublished archival evidence of a Byzantine Mosaic floor that lies under the earliest phase of the Al-Aqsa mosque. Sections of this floor were revealed during renovations that took place in the mosque after an earthquake in 1937 and was documented in the British Mandate Antiquities Department archives.[16]

Early Muslim – Most of the finds from the Early Muslim period (638-1099 C.E.) are architectural elements such as columns, capitals and marble slabs, ceramics, and floor tiles. Especially abundant are mother-of-pearl inlays and colorful glass wall mosaic tiles, some of them gold-plated, which probably originate from the original outer decorations of the Dome of the Rock. In addition, there are many coins and short inscriptions from this period.

Crusader – Solomon’s Stables, the area that was dug up to prepare for the new mosque, got its name in the Crusader Period (1099–1187 C.E.), when the Knights Templar used the area as stables. They had their headquarters in what later became the Al-Aksa Mosque, which they named “Solomon’s Temple.” We have found many items associated with Knights Templar activity, including hundreds of armor scales, horseshoe nails and a large collection of medieval arrowheads (photo).

In addition, we have recovered more than a hundred silver Crusader coins—the biggest and most varied collection of coins from this period found in Jerusalem. Many of these finds probably originate from the earth cleared directly from the interior of Solomon’s Stables at the start of the work there in 1996.

1187 until today – Among the many finds dating to the Mamluk and Ottoman Periods are remains from construction work which took place at the Dome of the Rock and the Al-Aqsa Mosque. These include glazed wall tiles, which were used on the outer walls of the Dome of the Rock beginning in the 16th century C.E., colorful window glass and more.

A dozen personal bronze seals were discovered, including one which belonged to ‘Abd al-Fatah al-Tamimi, who served as the deputy Mufti of Jerusalem during the 18th century. In addition, many Ottoman ammunition items were found, including lead and iron bullets, missile fragments, revolver parts and military insignia and badges. Finally, we have items left behind by western Christian pilgrims and visitors, ammunition items from the Six-Day War and a large variety of artifacts dating until the present day.

Yom Yerushalayim and the Temple Mount

In 1948, Jerusalem was split in half when the Jews who were living in the Old City surrendered to the Jordanian army and moved to Israeli West Jerusalem, and the area surrounding the Old City and the Old City itself became part of Jordan, and known as East Jerusalem. In 1967, the city was united under Israeli rule and one year later, to commemorate this unification, the Israeli government declared a national holiday called Jerusalem Day (יום ירושלים), to be celebrated yearly on the 28th of Iyyar.

Ironically, even after Mordechai (Motta) Gur’s famous line, הר הבית בידינו, “The Temple Mount is in our hands,” this area remains only nominally Jewish, since it currently functions as a holy site only for Muslims, as it has for a millennium. And because it cannot be excavated and has never been systematically excavated, we know precious little from archaeological digs about the site’s material history, other than what remains on the surface.

Although the destruction of the site by bulldozers was an archaeological travesty, the silver lining of this cloud has been the Temple Mount Sifting Project, which has given us a glimpse into the historical treasures buried in the ancient underground ruins of the Temple Mount.

Postscript

The Polemic that Should Not Be

Over the past few decades, a new narrative has been advanced by some, which denies any Jewish connection to the site, denying even the existence of the Temples on the Temple Mount. This revision of history has no academic merit, but has gained traction in certain circles.[17] Although from a critical standpoint it seems unnecessary to try and disprove this imaginary reconstruction of history, the many dateable findings of the sifting project make it clear—as if it weren’t already clear from the massive and visible remains related to the Second Temple such as the Western Wall—that this historically baseless claim is archaeologically baseless as well.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

May 11, 2018

|

Last Updated

March 25, 2024

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Footnotes

Dr. Gabriel Barkay is the co-founder and co-director of the Temple Mount Sifting Project and a lecturer on archaeology at Bar-Ilan University. He holds a Ph.D. in archaeology from Tel Aviv University, and was awarded the Jerusalem Prize in 1996. During Barkay’s large-scale excavation of Jerusalem’s Ketef Hinnom, his team discovered silvers scrolls from the 7th century containing a version of the Torah’s “Priestly Blessing.”

Zachi Dvira (Zweig) is the co-founder and co-director of the Temple Mount Sifting Project and a Ph.D. candidate at Bar-Ilan University. Among Dvira’s articles are, “New Information from Various Temple Mount Excavations from the Last Hundred Years,” “Using Data Mining Techniques for the Analysis of Pottery from Tell es-Safi/Gath,” and “Hebrew Clay Sealing from the Temple Mount and the Temple Treasury” (forthcoming).

Essays on Related Topics: